Misinformation: The evidence on its scope, how we encounter it, and our perceptions of it

The production and spread of misinformation have become major concerns for scholars, policy makers, and commentators across the world. Although some argue misinformation is as old as communication itself, the debate around its causes and impact has grown in recent years thanks to the role it has played in political campaigns, how it has amplified or stoked ethnic tensions around the world, and how it has muddied scientific consensus and health interventions.

While misinformation problems are driven by political and social forces that vary from country to country, they are also rooted both in broader changes across the media environment and in efforts by various actors to use and abuse digital technologies. Given this, researchers at the Reuters Institute for the study of Journalism have been investigating the ways in which media outlets and technologies shape, mediate, and reflect misinformation problems. This post provides a short overview of key research from the Reuters Institute that has addressed global misinformation problems.

The role of social media and search engines

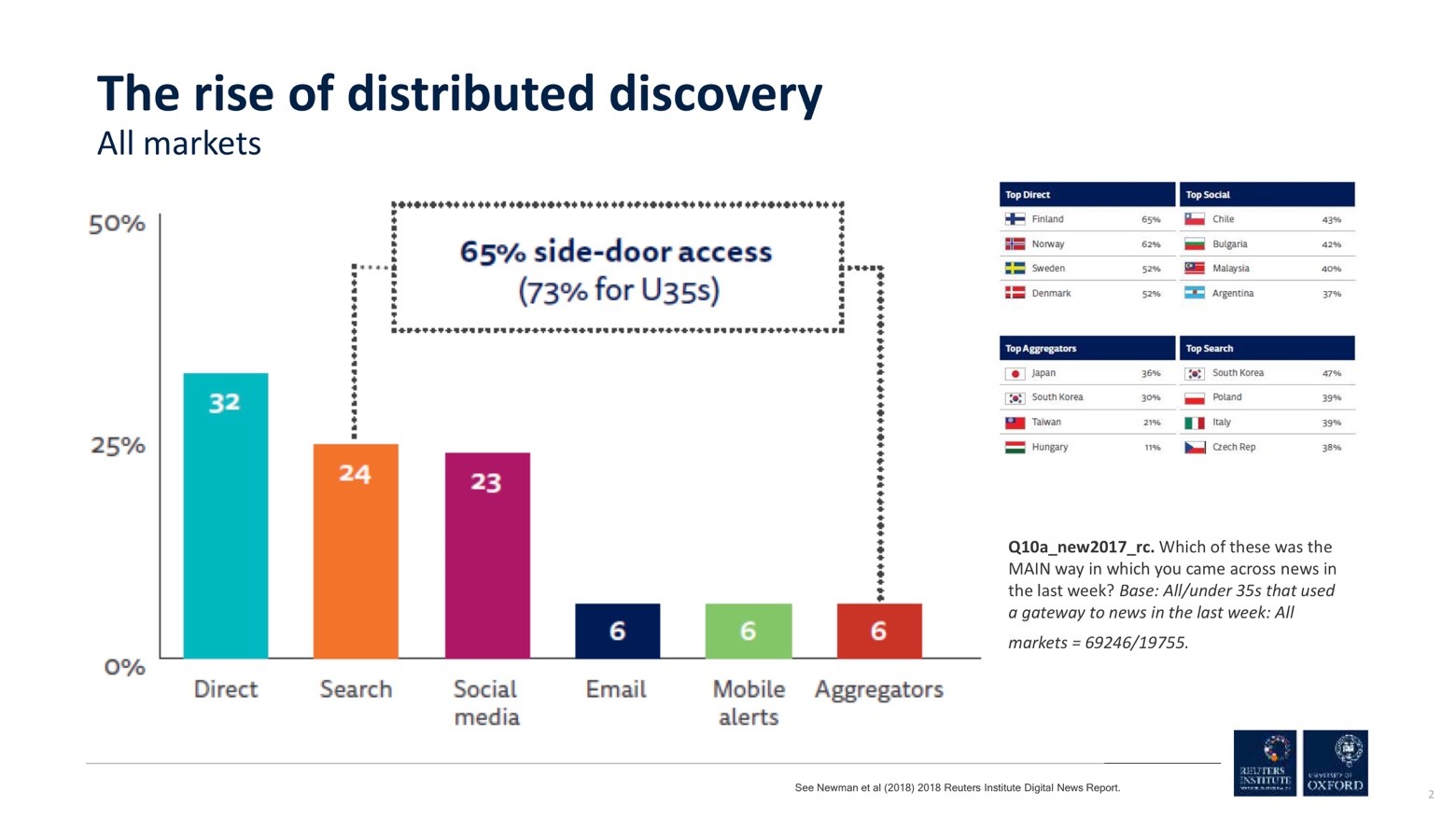

Rather than accessing news organisations directly, people are increasingly discovering news content through social media and search (see Figure 1). Despite some variation, this pattern is observed across countries. Our findings document the central role that platforms are now playing in the distribution of online content—both information and misinformation. People sometimes engage directly with sources of misinformation. But they can also arrive at misinformation (as they arrive at much else) side-ways via search engines, social media, or other forms of distributed discovery.

Figure 1: The Rise of Distributed Discovery Across the World

From Newman et al Digital News Report 2018. Q10a_new17_rc. Which of these was the MAIN way in which you came across news in the last week? Base all/under 35s that used a gateway to news in the last week: All markets = 69246/19755

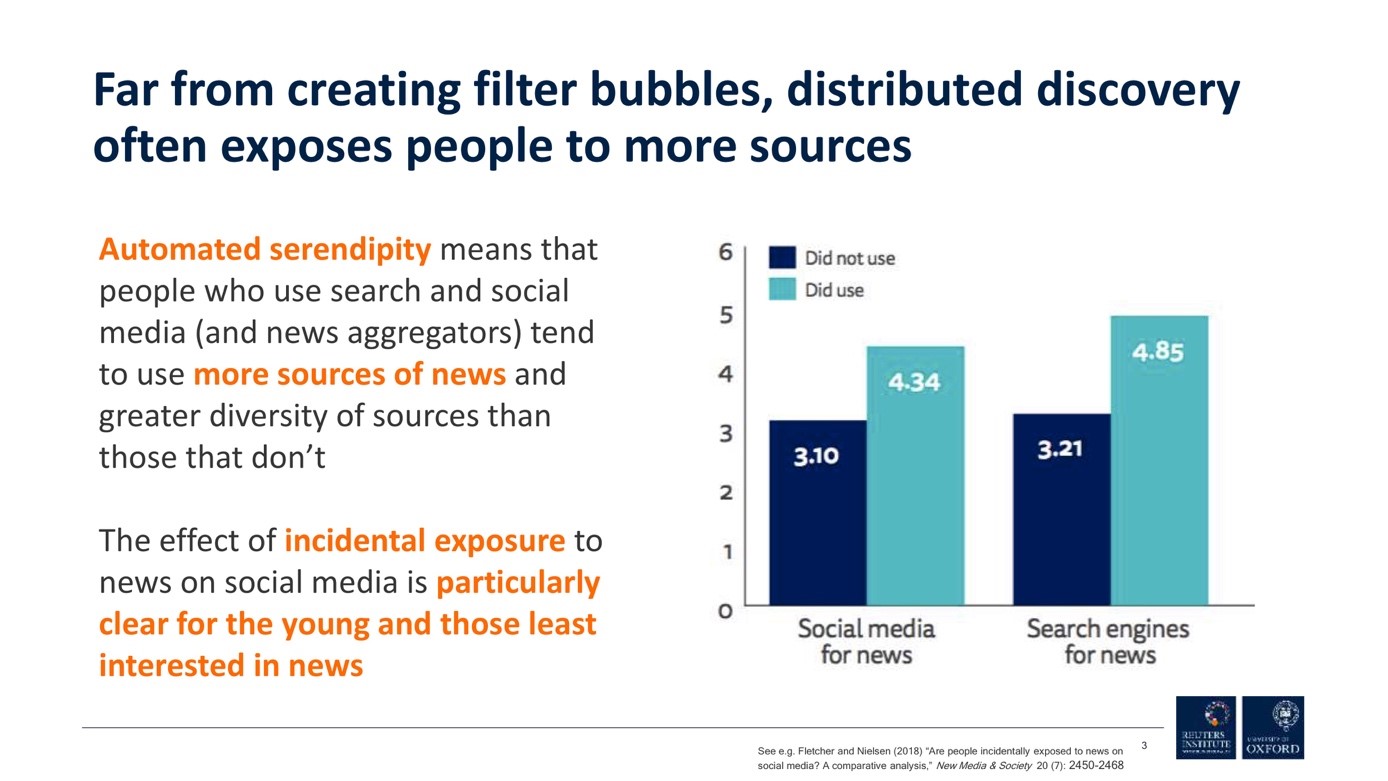

For decades, some commentators have expressed concern that the rise of distributed discovery facilitates filter bubbles or the formation of echo chambers. However, our research consistently finds that the use of search engines and social media are associated with more and more diverse news use (see Figure 2). This is driven by a combination of automated serendipity, forms of algorithmic selection that expose people to news sources they would not otherwise have used, and incidental exposure where people come across news while using platforms for other purposes.

From Newman et al., Digital News Report 2017. Q5B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news ONLINE in the last week? Please select all that apply. Q10. Thinking about how you got news online (via computer, mobile, or any device) in the last week, which were the ways in which you came across news stories? Please select all that apply. Base: Used/did not use social media for news/search engines for news in the last week: All markets = 28,557/43,238 16,893/54,902

However, distributed discovery raises several issues for news consumption. Notably, it can obscure the producers of news content, create openings for various purveyors of disinformation, and is associated with lower trust. While there has been a well-documented decline in trust across news organisations and countries (e.g Newman et al. 2018), we find that trust in news accessed via search and social media is notably lower than that approached directly.

Public perceptions of the problems of misinformation

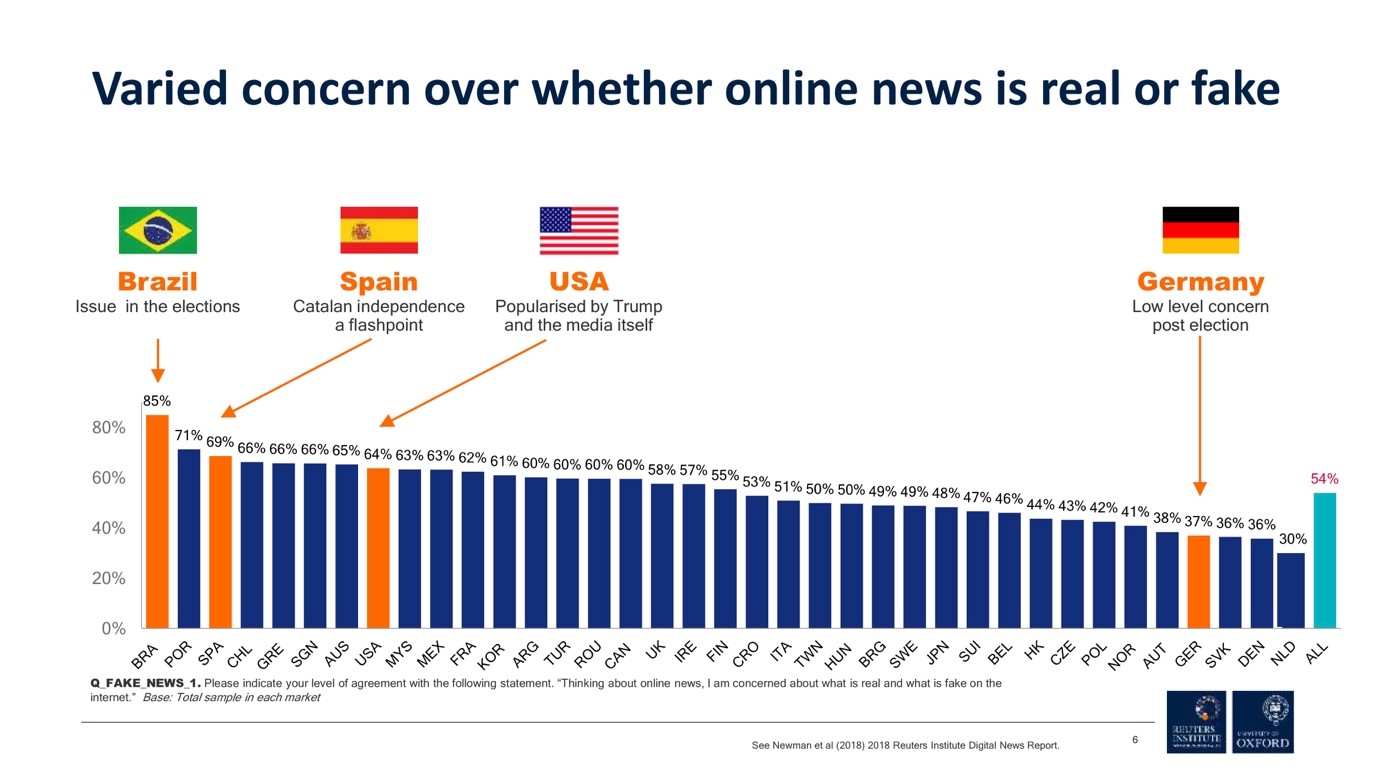

The move to distributed discovery is playing out, with some variation, globally, but public levels of concern over problems of misinformation vary, and people’s perception of these issues are not aligned with elite and policymaker debates. When asked, considering online news if they are concerned about what is real or fake on the internet, people in different countries express very different levels of concern, ranging from 85 percent concerned in Brazil, to only 30 percent in the Netherlands (Figure 3).

From Newman et al, Digital News Report 2018. Q_FAKE_NEWS_1. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement. ‘Thinking about online news, I am concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet.’ Base: Total sample in each market.

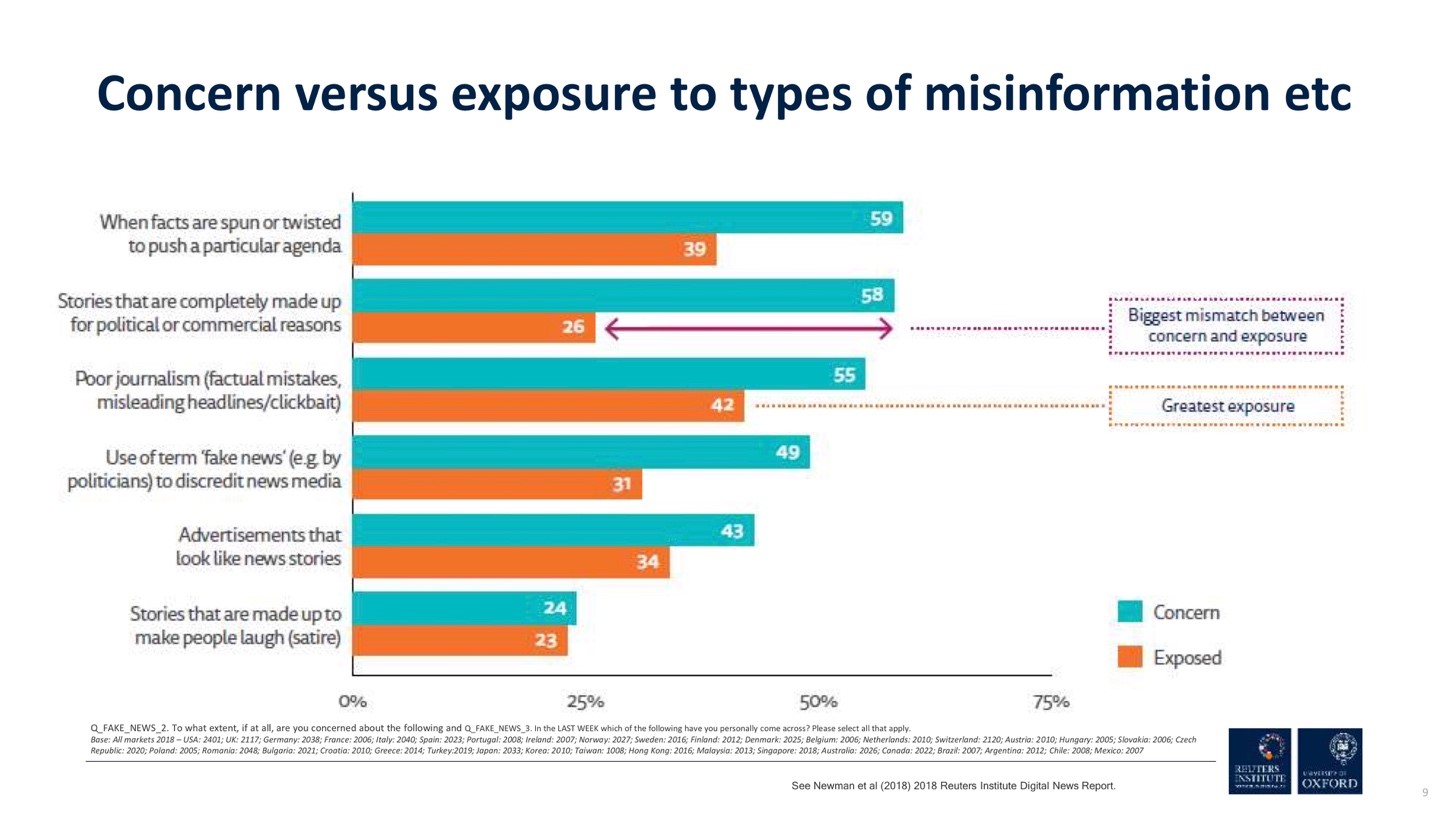

Much of the public also see problems of misinformation as much wider than narrow concerns over key issues like foreign information operations or completely fabricated for-profit content. When asked to name examples of what they consider to be “fake news”, focus group participants named many different types of content, including satire, poor journalism, political propaganda, and some forms of advertising. Notably, audiences see the difference between the latter three of these as one of degree; many see the line between news and “fake news” as a difference of degree and not a categorical distinction.

When asked about levels of concern, people are mostly concerned over what they consider to be political propaganda, poor journalism, as well as false news more narrowly defined as stories completely made up (whether for political or commercial reasons), a much wider set of issues than normally discussed in elite and policymaker circles. When asked about these different issues, people report greater exposure to what they consider to be examples of political propaganda and poor journalism than to made-up stories, even as they are equally concerned about this type of problem (see Figure 4).

From Newman et al. Digital News Report (2018). Q_FAKE_NEWS_2. To what extent, if at all, are you concerned about the following and Q_FAKE_NEWS_3: In the LAST WEEK which of the follow have you personally come across? Please select all that apply. Base: 69246

Scale and scope of misinformation problems

Despite the global scale of concern over misinformation and the very real problems that clearly exist, empirical research on the broader scale and scope in different countries is limited. We have used data on web site traffic and Facebook interactions to estimate the reach of and engagement with sites in France and Italy identified by independent domestic fact-checkers as problematic (as well as with sites backed by the Russian state). We found that the reach of the problematic sites and the time spent on them were small fractions of those of established news sites in both countries. That was also the case for most when looking at the number of Facebook interactions, though a small number of the problematic sites generated a very large number of Facebook interactions—larger even then some of the established news outlets. While these findings suggest that false news has had a more limited reach in France and Italy than is sometimes assumed, they also demonstrate how social media can be platforms for a wide dissemination of misinformation.

A recent report demonstrates how three digital-born outlets in the Global South are innovating new reporting and storytelling practices in order to confront growing problems of disinformation. The report shows how the Rappler in the Philippines, Daily Maverick in South Africa, and The Quint in India are attempting to leverage efforts to combat disinformation into new revenue streams by differentiating them from competitors, giving them a more compelling case for building, for example, membership models, and helping them acquire expertise that can be monetised through consultancy services and other business-to-business channels.

Recognising that the problems of misinformation are situated within the complex dynamics of changing global media systems, Reuters research has contextualised misinformation within broader trends and shifts in news production, distribution, and audiences. Moving forward, Reuters researchers will continue to adopt diverse approaches to understand and investigate the global problems of misinformation.