This year’s report comes at a time of deep political and economic uncertainty, changing geo-political alliances, not to mention climate breakdown and continuing destructive conflicts around the world. Against that background, evidence-based and analytical journalism should be thriving, with newspapers flying off shelves, broadcast media and web traffic booming. But as our report shows the reality is very different. In most countries we find traditional news media struggling to connect with much of the public, with declining engagement, low trust, and stagnating digital subscriptions.

An accelerating shift towards consumption via social media and video platforms is further diminishing the influence of ‘institutional journalism’ and supercharging a fragmented alternative media environment containing an array of podcasters, YouTubers, and TikTokers. Populist politicians around the world are increasingly able to bypass traditional journalism in favour of friendly partisan media, ‘personalities’, and ‘influencers’ who often get special access but rarely ask difficult questions, with many implicated in spreading false narratives or worse.

These trends are increasingly pronounced in the United States under Donald Trump, as well as parts of Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, but are moving more slowly elsewhere, especially where news brands maintain a strong connection with audiences. In countries where press freedom is under threat, alternative ecosystems also offer opportunities, at their best, to bring fresh perspectives and challenge repressive governments. But at the same time these changes may be contributing to rising political polarisation and a coarsening debate online. In this context, our report uncovers a deep divide between the US and Europe, as well as between conservatives and progressives everywhere, over where the limits of free speech should lie – with battle lines drawn over the role of content moderation and fact-checking in social media spaces.

This year’s survey also highlights emerging challenges in the form of AI platforms and chatbots, which we have asked about for the first time. As the largest tech platforms integrate AI summaries and other news-related features, publishers worry that these could further reduce traffic flows to websites and apps. But we also show that in a world increasingly populated by synthetic content and misinformation, all generations still prize trusted brands with a track record for accuracy, even if they don’t use them as often as they once did.

With growing numbers of people selectively (and in some cases consistently) avoiding the news, we look into the potential benefits of using new generative AI technologies to personalise content and make it feel more engaging for younger people. Our report, which is supported by qualitative research in three markets (the UK, US, and Norway), also includes a chapter on the changing state of podcasting as the lines blur with video talk shows and explores the prospects for charging for audio content. We also investigate where the value lies in local news and what appetite there might be towards more flexible ways of paying for online content, including ‘news bundles’.

This fourteenth edition of our Digital News Report, which is based on data from six continents and 48 markets, including Serbia for the first time, reminds us that these changes are not always evenly distributed. While there are common challenges around the pace of change and the disruptive role of platforms, other details are playing out differently depending on the size of the market, long-standing habits and culture, and the relationship between media and politics. The overall story is captured in this Executive Summary, followed by Section 2 with chapters containing additional analysis, and then individual country and market pages in Section 3.

Key findings

-

Engagement with traditional media sources such as TV, print, and news websites continues to fall, while dependence on social media, video platforms, and online aggregators grows. This is particularly the case in the United States where polling overlapped with the first few weeks of the new Trump administration. Social media news use was sharply up (+6 percentage points) but there was no ‘Trump bump’ for traditional sources.

-

Personalities and influencers are, in some countries, playing a significant role in shaping public debates. One-fifth (22%) of our United States sample says they came across news or commentary from popular podcaster Joe Rogan in the week after the inauguration, including a disproportionate number of young men. In France, young news creator Hugo Travers (HugoDécrypte) reaches 22% of under-35s with content distributed mainly via YouTube and TikTok. Young influencers also play a significant role in many Asian countries, including Thailand.

-

News use across online platforms continues to fragment, with six online networks now reaching more than 10% weekly with news content, compared with just two a decade ago. Around a third of our global sample use Facebook (36%) and YouTube (30%) for news each week. Instagram (19%) and WhatsApp (19%) are used by around a fifth, while TikTok (16%) remains ahead of X at 12%.

-

Data show that usage of X for news is stable or increasing across many markets, with the biggest uplift in the United States (+8 points), Australia (+6), and Poland (+6). Since Elon Musk took over the network in 2022 many more right-leaning people, notably young men, have flocked to the network, while some progressive audiences have left or are using it less frequently. Rival networks like Threads, Bluesky, and Mastodon are making little impact globally, with reach of 2% or less for news.

-

Changing platform strategies mean that video continues to grow in importance as a source of news. Across all markets the proportion consuming social video has grown from 52% in 2020 to 65% in 2025 and any video from 67% to 75%. In the Philippines, Thailand, Kenya, and India more people now say they prefer to watch the news rather than read it, further encouraging the shift to personality-led news creators.

-

Our survey also shows the importance of news podcasting in reaching younger, better-educated audiences. The United States has among the highest proportion (15%) accessing one or more podcasts in the last week, with many of these now filmed and distributed via video platforms such as YouTube and TikTok. By contrast, many northern European podcast markets remain dominated by public broadcasters or big legacy media companies and have been slower to adopt video versions.

-

TikTok is the fastest growing social and video network, adding a further 4 points across markets for news and reaching 49% of our online sample in Thailand (+10 percentage points) and 40% in Malaysia (+9). But at the same time people in those markets see the network as one of the biggest threats when it comes to false or misleading information, along with Facebook, long a source of widespread public concern.

-

Overall, over half our sample (58%) say they remain concerned about their ability to tell what is true from what is false when it comes to news online, a similar proportion to last year. Concern is highest in Africa (73%) and the United States (73%), with lowest levels in Western Europe (46%).

-

When it comes to underlying sources of false or misleading information, online influencers and personalities are seen as the biggest threat worldwide (47%), along with national politicians (47%). Concern about influencers is highest in African countries such as Nigeria (58%) and Kenya (59%) while politicians are considered the biggest threat in the United States (57%), Spain (57%), and much of Eastern Europe including Serbia (59%), Slovakia (56%), and Hungary (54%).

-

Despite this, the public is divided over whether social media companies should be removing more or less content that may be false or harmful, but not illegal. Respondents in the UK and Germany are most likely to say too little is being removed, while those in the United States are split, with those on the right believing far too much is already taken down and those on the left saying the opposite.

-

We find AI chatbots and interfaces emerging as a source of news as search engines and other platforms integrate real-time news. The numbers are still relatively small overall (7% use for news each week) but much higher with under-25s (15%).

-

With many publishers looking to use AI to better personalise news content, we find mixed views from audiences, some of whom worry about missing out on important stories. At the same time there is some enthusiasm for making the news more accessible or relevant, including summarisation (27%), translating stories into different languages (24%), better story recommendations (21%), and using chatbots to ask questions about news (18%).

-

More generally, however, audiences in most countries remain sceptical about the use of AI in the news and are more comfortable with use cases where humans remain in the loop. Across countries they expect that AI will make the news cheaper to make (+29 net difference) and more up-to-date (+16) but less transparent (-8), less accurate (-8), and less trustworthy (-18).

-

These data may be of some comfort to news organisations hoping that AI might increase the value of human-generated news. To that end we find that trusted news brands, including public service news brands in many countries, are still the most frequently named place people say they go when they want to check whether something is true or false online, along with official (government) sources. This is true across age groups, though younger people are proportionately more likely than older groups to use social media to check information as well as AI chatbots.

-

One more relatively positive sign is that overall trust in the news (40%) has remained stable for the third year in a row, even if it is still four points lower overall than it was at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic.

-

As publishers look to diversify revenue streams, they are continuing to struggle to grow their digital subscription businesses. The proportion paying for any online news remains stable at 18% across a basket of 20 richer countries – with the majority still happy with free offerings. Norway (42%) and Sweden (31%) have the highest proportion paying, while a fifth (20%) pay in the United States. By contrast 7% pay for online news in Greece and Serbia and just 6% in Croatia.

Listen to a podcast episode on the chapter

Watch on YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Transcript

Jump to: Platform resets | News audiences on X | The rise of TikTok | Video networks | Do audiences prefer text or video? | News podcasts | Online misinformation | News literacy | Views on content moderation | Trust in news | How to raise it | News avoidance | Personalisation | The role of AI | AI-driven aggregators | Smartphone news use | Paying for news | Local news

Traditional news media losing influence – United States in the spotlight

If Donald Trump’s first-term victory was facilitated by mass exposure in the mainstream media and plenty of airtime from partisan outlets, this time around his success was at least in part due to his courting of an alternative media ecosystem that includes podcasters and YouTubers. That process has continued in office, with social media influencers and content creators invited to press briefings while some traditional media have found access denied. We can see some of the reasons for this change of approach through a number of data points in our survey.

First, the proportion accessing news via social media and video networks in the United States (54%) is sharply up – overtaking both TV news (50%) and news websites/apps (48%) for the first time. Eight years ago, the so-called ‘Trump bump’ raised all boats (or temporarily stalled their sinking), including access to news websites, TV, and radio, but this time round only social and video networks (and most likely podcasts too) have grown, supporting a sense that traditional journalism media in the US are being eclipsed by a shift towards online personalities and creators.

These shifts are in large part driven by younger groups – so-called digital and social natives. Over half of under-35s in the United States – 54% of 18–24s and 50% of 25–34s – now say that social media/video networks are their main source (+13 points and +6 points respectively compared with last year). But all age groups are prioritising social media to a greater extent – at the expense of traditional channels such as websites and TV news.

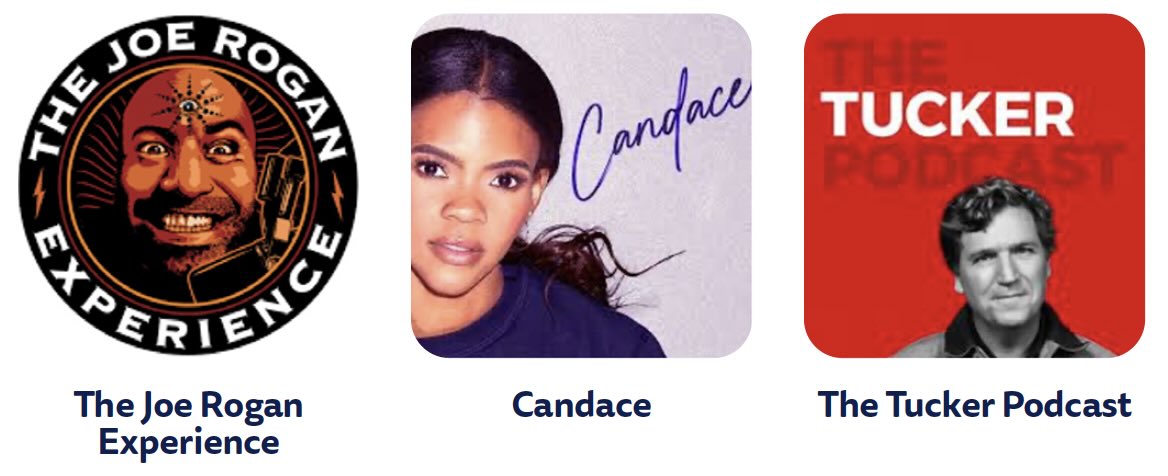

During the recent US election both main presidential candidates gave interviews to personalities and creators who have been building significant audiences via online platforms such as YouTube and X. In our survey we can see for the first time how influential some of these have become. One-fifth (22%) said they had come across podcaster and comedian Joe Rogan discussing or commenting on news in the previous week, with 14% saying the same about Tucker Carlson, the former Fox News anchor, who now operates content across multiple social media and video networks including X and YouTube. Other widely accessed personalities include Megyn Kelly, Candace Owens, and Ben Shapiro from the right and Brian Tyler Cohen and David Pakman from the left. Analysis from our Digital News Report 2024 shows that the vast majority of top creators discussing politics are men.

These are not just big numbers in themselves. These creators are also attracting audiences that traditional media struggle to reach. Some of the most popular personalities over-index with young men, with right-leaning audiences, and with those that have low levels of trust in mainstream media outlets, seeing them as biased or part of a liberal elite.

The rise of social media and personality-based news is not unique to the United States, but changes seem to be happening faster – and with more impact – than in other countries. The proportion that say social media are their main source of news, for example, is relatively flat in Japan and Denmark, though it has also increased in other countries with polarised politics such as the UK (20%) and France (19%). But in terms of overall dependence the United States seems to be on a different path – joining a set of countries in Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia where heavy social media and political polarisation have been part of the story for some time.

At the same time, we find a continued decline in audiences for traditional TV news, as audiences switch to online streaming for drama, sport, news, and more. TV news reach in France and Japan, for example, is down 4 points and 3 points to 59% and 50% respectively. Linear radio news, which had been relatively stable, is also on a downward trend, with younger audiences often preferring on-demand audio formats such as podcasting.

Taken together these trends seem to be encouraging the growth of a personality-driven alternative media sector which often sets out its stall in opposition to traditional news organisations, even if, in practice, many of the leading figures are drawn from these. Prominent YouTubers outside the United States include Julian Reichelt, a former editor of Bild in Germany, and Piers Morgan, a former newspaper editor and TV presenter in the UK, but mostly name recognition in Europe for these news creators is much lower than the US. One exception, which we also noted in last year’s report, is the young French creator Hugo Travers, better known by the pseudonym HugoDécrypte, who has built a popular media business based on YouTube and TikTok where he tries to explain the news to younger audiences. Our data suggest that he now has a level of reach with under-35s that is comparable with or higher than many French mainstream news organisations.

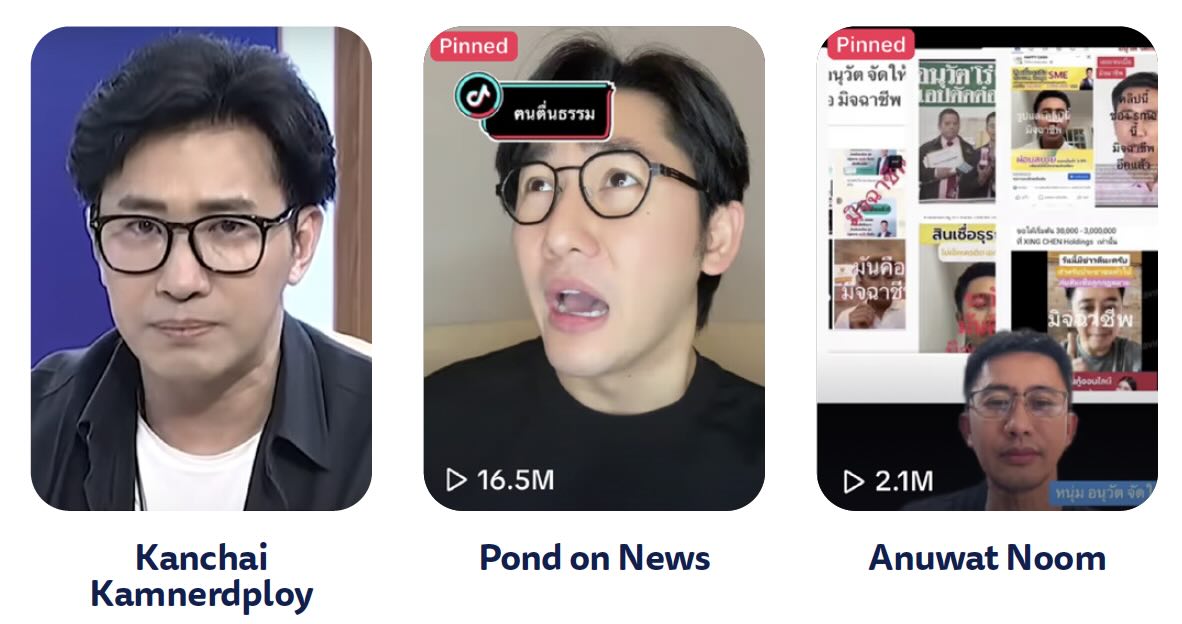

Young news creators are also having an impact in other parts of the world. In Thailand, where the limits of expression have often been tightly controlled, a generation of social media influencers are changing the nature of information consumption, making it more outspoken and less formal. Influential TikTokers include Anuwat Noom (5 million followers) and Phakkawat Rattanasiriampai (Pond on News) who has built an audience of more than 3 million followers for his concise and accessible takes on the news. Kanchai Kamnerdploy is an actor, journalist, and news anchor whose often controversial talk show is watched by millions via Facebook and YouTube, as well as via conventional TV. More than half our Thai respondents (60%) say they saw him discussing or commenting on news in the previous week.

In this sometimes-confusing alternative ecosystem the lines are often blurred between journalism, activism, and politics. In Romania, Călin Georgescu built his campaign for the presidency largely through regular appearances on far-right podcasts and a successful TikTok channel where he talked about his love of judo alongside his anti-EU and pro-Russian views. Despite being banned from participating in May’s rerun elections, Georgescu remains the most-mentioned individual as a source of news in social media by Romanian respondents.

Across all 48 markets, dependence on social media and video networks for news is highest with younger demographics, with 44% of 18–24s saying these are their main source of news and 38% for 25–34s. These groups also show a reluctance to visit news websites or apps, compared with those aged 35–54. We also added news podcasts and AI chatbots to this question for the first time and these newer sources are increasing the challenges of attention for traditional news media – amongst younger audiences in particular – a point we’ll return to later in this summary.

Platform resets and their impact on news media

Last year we showed how changes to platform strategies for social media companies such as Meta – including a pulling back from news and investing in video and creator content – were making it even harder for publishers to reach specific audiences. Following Trump’s victory, Meta announced – in another sharp turn of direction – that they will show more political content, but the effects of this, and what it means for publishers in different countries, are yet to be seen.

This year’s data show continuing strengthening of video-based platforms and a further fragmentation of consumption. There are now six networks with weekly news reach of 10% or more compared with just two a decade ago, Facebook and YouTube. Although these networks remain the most important for news amongst the basket of 12 countries we have been tracking since 2014, they are increasingly challenged by Instagram and TikTok with younger demographics. But Messenger (5%), LinkedIn (4%), Telegram (4%,) Snapchat (3%), Reddit (3%), Threads (1%), and Bluesky (1%) are also an important part of the mix for specific audiences or for particular occasions.

Elon Musk’s X audience shifts rightwards – no loss of overall reach

It is striking to see that X has not lost reach for news on aggregate across our 12 countries despite a widespread X-odus by liberals and journalists, including some prominent news organisations, some of whom have relocated to Threads or Bluesky.1 It may be that X’s reach is less affected than regular engagement, which industry research suggests had been declining before Trump’s return to the White House.2

In the US at least, the election and its aftermath seems to have re-energised the network. Our poll, which was conducted in the weeks after the inauguration, showed that the use of X for news was 8 points higher than the previous year, reaching almost a quarter (23%) of the adult population.

When analysing the change in Twitter/X’s audience over time in the US (see next chart) we can see how Jack Dorsey’s Twitter (pre-2022) was populated mostly by those on the progressive side of the political spectrum, but the proportion that self-identify on the right tripled after Elon Musk took over. The billionaire has courted and platformed conservative and right-wing commentators while using his own account to boost Donald Trump and champion ‘free speech’ causes. Several studies have shown how X’s influential algorithm is also now pushing right-leaning perspectives including his own (Graham and Andrejevic 2024) which may have contributed to this shift in audience.

Across countries we see similar trends with right-leaning audiences (and creators) increasingly drawn to the platform. In the UK right-leaning audiences have almost doubled since the X makeover and progressive audiences have halved. Elon Musk has used his own account (219m followers) to label Britain a ‘police state’ due to its measures against rioters involved in violent clashes last summer, advocated for the release of a jailed far-right activist, and accused Prime Minister Keir Starmer of failing to act against gangs that sexually exploited girls.3 Across our wider group of 12 countries, we find similar trends with right-leaning audiences now level or slightly ahead.

These data show the challenge for news media that say they are putting fewer resources into the platform due to lower engagement and a hostile environment (Newman and Cherubini 2025), but worry that journalism could be ceding important ground to content creators and influencers peddling opinions not based in evidence.

TikTok growth continues for news

While X remains a powerful force in the United States and a few other countries, the most significant story elsewhere is fast-growing news consumption on TikTok, as well as consistently high levels of news use via YouTube and Facebook.

Overall, a third (33%) of our global sample use TikTok for any purpose and about half of those use the app for news (17%). The fastest growth is in Thailand, where almost half of our sample (49%) now uses TikTok for news, up 10pp on last year, but there are increases everywhere, especially with younger groups. TikTok use is much lower in the United States (12%) and Europe overall (11%), though stronger with younger demographics.

Weekly YouTube use, for any purpose, is up 2 percentage points on aggregate to 63%, with news use stable at 30%. Once again, we find the heaviest news users of this video platform are in Africa and parts of Asia. Over half of our samples in India, Thailand, and Kenya say they use YouTube for news. Growth has been driven by relatively cheap data charges along with lower literacy levels historically, preferring video formats.

Rise of video networks increases pressure on news media

Traditional social networks such as Facebook and Twitter were built around the social graph – effectively this meant content posted directly by your friends and contacts. But video networks such as YouTube and TikTok are driven much more by creator-content and ‘must see’ hits.

For several years we have asked where people pay attention when using social networks and have found that mainstream media is at best challenged by – at worst losing out to – these online creators and personalities, even when it comes to news. This trend is evident again this time in data aggregated across all 48 markets. Creators now play a significant role in all the networks apart from Facebook, with traditional media gaining least attention on TikTok. This is not surprising as publishers have struggled to adapt journalistic content in a more informal space as well as worrying about cannibalising website traffic by posting in a network that is not set up for referral traffic.

We changed the question codes this year to allow us to distinguish news creators (those that mainly post about news) from personalities and celebrities (that occasionally talk about news). It is a blurry dividing line for many respondents but when exploring these richer data (including alternative media, politicians, and ordinary people) we get a more detailed understanding of the dynamics in different countries. For example, when looking at X in the UK we find that mainstream media brands still capture most attention, whereas in the United States competition from other news media, politicians, and news creators is much stronger, reflecting the personality and influencer-led trends we discussed earlier.

The contrasts are even more striking when we compare the use of TikTok in Norway and Kenya. Both countries have a relatively high number of (mostly young) people using TikTok for news, but the attention profile is very different. Traditional news brands still attract most attention when consuming news on TikTok in Norway, but news creators/influencers and politicians play a much bigger role in Kenya.

Drilling down into the most mentioned TikTok accounts that people cite in open comments, in Norway, we find most mentions for traditional news brands such as VG and TV2 that have both invested significantly in the platform. VG for example has used TikTok to simplify complex investigative stories into visually engaging formats tailored for Gen Z audiences.4 In Kenya by contrast, top brands like Citizen are challenged by news creators such as The News Guy (right) and Crazy Kennar, a comedian and digital content creator best-known for skits that capture the everyday experiences of ordinary Kenyans (1.8m followers on TikTok). This qualitative analysis shows how ‘news’ in these social networks blurs previously separate genres such as news, comedy, and even music.

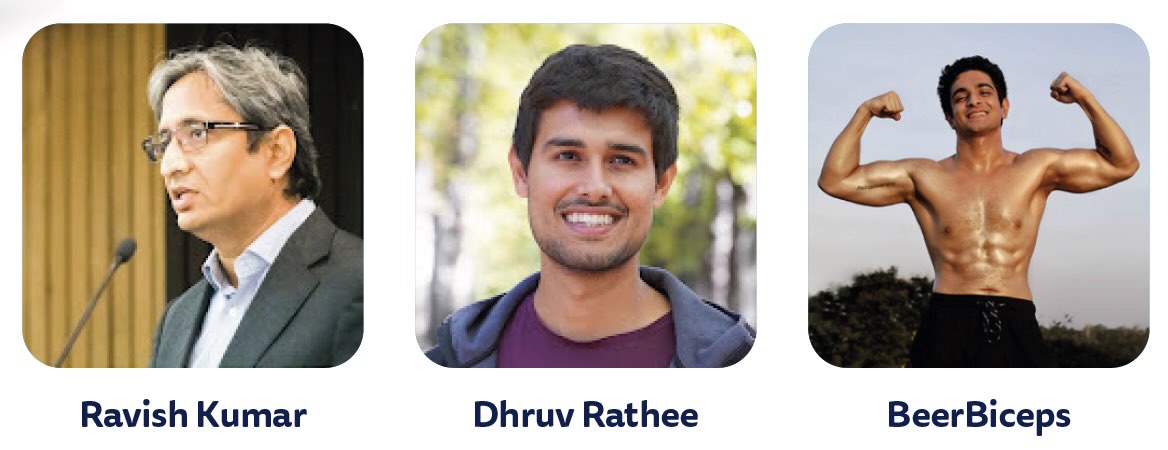

YouTube content in India has been exploding in recent years with a host of successful talk shows that are both critical of and supportive of the government of Narendra Modi. Ravish Kumar (12m followers) is a former NDTV anchor, focusing on political commentary and social issues, while Dhruv Rathee (25m followers) creates educational videos on social, political, and environmental issues, aiming to simplify complex topics for a broad audience. Shows like The Deshbhakt (5.5m followers), hosted by Akash Banerjee, offer satirical takes on Indian politics. Other colourful parts of the Indian manosphere include Ranveer Allahbadia, popularly known as BeerBiceps, who covers fitness, lifestyle, fashion, and entrepreneurship, aimed at young Indians.

Some of the most popular Indian YouTubers mentioned in the context of news

Amongst the most-named news creators in Brazil, we find Gustavo Gayer, an internet celebrity and right-wing politician who has courted both controversy and conspiracy theories. His channel, which has 1.9m followers, claims to ‘spread the truth' and prevent more young people from ‘falling into the ideological dungeon of the Left’. Other frequently mentioned individuals that occasionally talk about news include comedian and digital influencer Carlinhos Maia and lifestyle creator Virgínia Fonseca, who have 34m and 54m followers on Instagram respectively.

Underlying preferences are shifting too

We’ve already explored the growing importance of online video news and news podcasts at a headline level but it is interesting to consider this in relation to text, which is still the dominant way in which most people access news. To what extent is this changing and with which demographics?

Overall, we find that audiences on average across all markets still prefer text (55%), which provides both speed and control from a consumers’ perspective, but around a third (31%) say they prefer to watch the news online and more than one in ten (15%) say they prefer to listen. Country differences are particularly striking, with more people saying they prefer to watch rather than read or listen to the news in India, Mexico, and the Philippines. By contrast the vast majority still prefer to read online news in Norway, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

But even in countries with strong reading traditions such as Germany (see next chart), the UK, and all of the Nordic markets, we find striking generational differences. Younger groups, especially those aged 18–24, are much more likely than older ones to prefer watching – or listening to – the news. This suggests that over time publishers may need to adjust resources in the newsroom to produce less text and more audio-visual content.

This very clear story about preferences is supported by data that show that consumption of online video has also jumped significantly in the last two years, after a period where it had remained relatively static. In the United States, for example, the proportion consuming any news video weekly has grown from just over half (55%) in 2021 to around three-quarters (72%) today. The majority of this consumption is accessed via third-party platforms (61%) such as Facebook, YouTube, X, Instagram, and TikTok rather than via news websites or apps (29%), adding further evidence to the narrative about the diminishing influence of legacy media.

Across all markets the proportion consuming social video news has grown from 52% in 2020 to 65% in 2025 and any video from 67% to 75%. A big part of the change has been the shift of platform strategies which has seen networks like Facebook, Instagram, and X prioritising video more in their algorithms, while Google has added a short video tab to its search results. At the same time, publishers have been producing more videos of various duration and showcasing them more prominently within their websites and apps. The Economist is amongst publishers to have added a vertical video carousel on its home page, while the New York Times has incorporated short social media-inspired videos as a way of bringing out the personality of its reporters.

A number of other countries such as the UK and France have seen a similar step change in video consumption in the last two years, again mostly via third-party platforms. But in Finland, Norway, and Sweden we find a different pattern, with almost as much video consumption coming from destination websites. This is partly because commercial and public service broadcasters in the Nordic regions have invested heavily in their own native video players and have restricted the amount of content they post to platforms like YouTube or X. Social media consumption is still mostly ahead, but the gap is closing and in Finland there is now more consumption onsite than via all third-party platforms put together.

The changing shape and growing influence of news podcasting

Podcasting started life more than 20 years ago as a way of accessing and distributing audio programming in a more convenient way. Audiences were often small, there was no commercial model, and listeners were passionate about the grass-roots nature of the medium. But in the last few years many of these assumptions are being challenged with much larger audiences, greater professionalisation, and an increased overlap with video.

Our previous research shows that around a third of our global audience accesses some type of podcast monthly, including specialist, sport, entertainment, and a range of lifestyle content, but this year we have changed our approach, focusing more closely just on the news and current affairs category. By adding podcasts to our news consumption question we are able to compare weekly usage for the first time with radio, television, and print news, as well as other digital sources.

This new question still shows significant differences across countries, with higher weekly usage of news podcasts in the United States (15%), reflecting strong investment by publishers, independent producers, and advertisers over the last few years. Our data suggest that in the US a similar proportion now consume news podcasts each week as read a printed newspaper or magazine (14%) or listen to news and current affairs on the radio (13%). Nordic markets such as Denmark (12%), Sweden (11%), and Norway (11%) also have well-developed news podcast markets, but traditional radio remains much more important there (33% average weekly news reach across Northern Europe). In other parts of the world such as Italy (6%), Argentina (4%), and Japan (3%) the podcast market is more nascent.

In this year’s report we also asked an open survey question about which news podcasts people pay most attention to and we conducted qualitative research in a number of markets including the United States, exploring motivations for listening, as well as watching.

In the United States we find a clear split between analysis-led shows from legacy brands – such as The Daily (New York Times) and Up First (NPR) – and personality-led podcasts that mostly deal in commentary or point of view. Much of the latter overlaps with the growth of the (mostly right-leaning) alternative media ecosystem that we described earlier. In many cases their primary output is not audio but video, with YouTube now the main channel for podcast distribution in the United States. By contrast Spotify is the most popular podcast platform in the UK and Germany, along with public service media apps such as BBC Sounds and ARD Audiothek.

Personality-led, often consumed in video

Legacy news brand-led, mostly audio

Outside the US we tend to find that legacy media brands still play a bigger role, especially programmes produced by public service media. Having said that, in the United Kingdom commercial companies such as Goalhanger and Global Radio are providing strong competition for the BBC, with shows such as The Rest is Politics and the News Agents most mentioned by respondents. These commentary-based shows tend to be filmed for YouTube with highlight clips used to drive new audiences on TikTok and Instagram.

As we've pointed out in the past, news podcast consumption is higher amongst the under-35s, as well as those with higher incomes and education. This group is particularly appealing for news organisations looking to attract the next generation of subscribers. To that end publishers have started to experiment with a range of payment options that include early access, extra content, and even separate subscriptions at a lower price point. The Economist has around 30,000 subscribers paying $5/£5 a month for its podcast+ package and the New York Times charges a similar amount for some premium content including older episodes.

Exploring the question of payment further we find that 42% of news podcast listeners, across 20 countries we have been tracking for some time, say they would be willing to pay a reasonable price for news-related podcasts they like. The figure tends to be higher in countries with greater consumption and where the market offering is more developed. The affordances of podcasting, which include a deep connection to the host and a considerable amount of time spent listening, could be a key factor in this relatively high willingness-to-pay figure. A high proportion of people (73%) also say listening to podcasts helps them understand issues at a deeper level.

Online misinformation and news literacy

As audiences are exposed to a wider range of non-traditional news sources through social media and other platforms, a number of international organisations have expressed concern about the implications for society and democracies around the world. The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report (2025)5 identified misinformation and disinformation as the most pressing risks for the next two years, highlighting threats such as AI-generated fakes and declining trust in institutions.

In our survey, more than half of our respondents worldwide (58%) agree that they are worried about what is real and fake online when it comes to news – a similar number to last year, but 4 points higher than in 2022. Concern is highest in Africa (73%) where social media are widely used for news across all demographics, as well as the United States (73%), and lowest in Europe (54%). But it is important to put expressed concern in perspective, given that research shows that this is often driven by narratives they disagree with or perceptions of bias, rather than information that is objectively ‘made up’ or false (Nielsen and Graves 2017).

In many countries, leading national politicians are considered by respondents to pose the biggest threat, especially in the United States where Donald Trump’s second term has been marked by a strategy of ‘flooding the zone’, often with misleading information or false statements (e.g. that Ukraine started the war with Russia6). He has long used the term ‘fake news’ to vilify media critical of his policies.

In many African and Latin American countries, as well as parts of Asia, there is equal concern around the role of online influencers or personalities. A recent investigation by the news agency AFP in Nigeria and Kenya found that prominent influencers were hired by political parties or candidates in both countries to promote false narratives in social media.7

At the same time, a significant group (32%) believes that journalists are a big part of the problem. This is especially the case in countries where mainstream media are seen to be unduly influenced by powerful agendas (e.g. Greece and Hungary). In polarised markets such as the United States, those that identify on the right are also much more inclined to see news media as a major threat, with many believing that they deliberately misinform the public and work to a liberal agenda.

When it comes to the networks through which misleading or false information might be spread, Facebook and TikTok are seen as creating the biggest threat across markets. Facebook has been at the centre of public concern since we first asked about these issues, whereas TikTok has overtaken other long-established platforms in this regard. In Germany, Ireland, and the UK, X is considered to be an equally serious threat, with concerns about the lack of moderation feeding unrest in Dublin and UK cities in 2023 and 2024, as well as Elon Musk’s interventions in domestic politics angering many.

Messaging apps such as WhatsApp are mostly considered less of a threat, as discussion tends to be more contained within trusted groups of friends. One notable exception is India, the messaging app’s largest market, where fake news, including videos circulating in large groups, have in the past incited mob violence (and deaths).8 Just over one in ten (11%) think that people they know (including friends and family) also play a role in spreading misinformation.

In this year’s report we have explored the tactics and approaches audiences use when they want to check information that they think might be false. One important finding that will encourage many in the news industry is that the biggest proportion of respondents say they would first look to news outlets they trust (38%), official sources (35%), and fact-checkers (25%) rather than sources such as social media (14%). Having said that, younger users were proportionately more likely than other groups to check social media, including by reading comments from other users to help them make up their minds, as well as using AI chatbots. This highlights how younger groups have developed a ‘flatter’ pattern of trust in media than older generations, gathering information without a shared sense of a ‘hierarchy of validation’.9

Search engines (33%) are another important way in which people check for information but probing further we found that their underlying intent was to find the same trusted sources. In each case respondents were able to identify the specific brands they would turn to in each country (see next chart). In the UK, Germany, and Japan the majority – including those from both left and right – said they would turn to public service broadcasters or their websites, (BBC News, ARD, and NHK), with commercial sites a distant second, but in the United States people turned to the news brand that they identified with most politically – CNN for left-leaning respondents and Fox News for more right-leaning ones. In South Africa, consumers turned in equal numbers to commercial brands and the public broadcaster (SABC). These data show the continuing importance of independent public media brands as an anchor point in an uncertain world – and at moments of national and international significance – even if people don’t use them as often as they once did.

Most mentioned news brands for checking whether something was false, misleading, or fake – Selected countries

Fact-checking brands have much lower name recognition overall, with the exception of the United States where services like Snopes and Politifact play a significant role in the public conversation. Elsewhere, publishers have been doubling down on their own fact-checking services, including BBC Verify in the UK and the Daily Maverick’s FactCheck hub in South Africa in association with NPO Africa Check.

News literacy makes less difference than you might think

We also asked in this year’s survey about whether people had received any education or training – formal or informal – on how to use news. Across markets we find that only around a fifth (22%) of our global sample have done so but young people were roughly twice as likely to say they have had news literacy training compared with older groups (36% U35s compared with 17% 35+ globally). A number of Nordic markets, including Finland (34%), had the highest levels of news literacy training. France (11%), Japan (11%), and most of the countries in Eastern Europe and the Balkans had the least.

We do find that those who have engaged in news literacy training are slightly more trusting of news than those that have not, but this may just be a function of higher levels of education overall. When checking information, these groups tend to use more different approaches on average than those that have had no training – including visiting trusted sources, fact-checking websites, official sources, and politicians, but this exposure to different perspectives may also be making them more sceptical. Those that have had literacy training are more concerned about misinformation – and are more likely to see social and video networks as a major threat (83% compared with 74%).

How audiences view the issue of content moderation in social media

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump strongly opposed content moderation and fact-checking on social media platforms, which he suggested, without offering systematic evidence, censor conservative voices and ‘stifle free speech’.10 Just days before Trump took office, Meta’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced it would be abandoning Facebook and Instagram’s long-standing fact-checking programmes in the United States and replacing them with X-style ‘community notes’, where comments on the accuracy of posts are managed by users. All this comes as European governments are moving in the opposite direction, looking to work more closely with fact-checkers on an EU-wide disinformation code, aiming to reduce hate speech and protect the integrity of elections. Worries have grown since the Romanian presidential elections were annulled in December 2024 amid allegations about Russian interference. Against this background we asked users how they felt about the removal of content that could be seen as harmful or offensive, even if it was not illegal.

Across our entire sample, people were almost twice as likely to say that platforms were removing too little rather than too much (32%/18%). This view is particularly strong in the United Kingdom where new rules are starting to be enforced requiring platforms to do more to counter harmful content and make them safer by design,11 as well as in Germany. But it is a very different story in the United States and Greece where opinion is more split.

These differences around where the limits of free speech should lie are shaped in part by Europe’s history on one side and the US commitment to the First Amendment on the other. But even within the United States we find striking divisions too between those that identify on the left and the right. Almost half of those on the right (48%) think too much is already being removed, whereas a similar proportion of those on the left (44%) think exactly the opposite.

Across all 48 markets, those on the left also want more content moderation, but those on the right are much more evenly split. Younger people are also in favour of more content moderation in general, but are less likely to say that than older groups, perhaps because they have grown up seeing and managing a wider set of perspectives in social media.

Trust in the news

Despite a clear decline over the last decade, we find that levels of trust in news across markets are currently stable at 40%. Indeed, they have been unchanged for the last three years. But we do find significant differences at a national level. Finland has amongst the highest levels of trust (67%), with Hungary (22%), Greece (22%), and other countries in Eastern Europe bumping along the bottom. Some African countries such as Nigeria (68%), and Kenya (65%) also have high trust scores, but it is important to bear in mind that these are more educated, English-speaking survey samples so are not directly comparable. In these countries, we also find that high trust levels often co-exist with lower levels of press freedom. In Nigeria, for example, RSF (Reporters Without Borders) says governmental interference in the news media is significant.

In examining changes over time, we find that some bigger European countries such as the UK and Germany have seen a significant decline in levels of trust around news (-16 points and -15 respectively since 2015). In both countries, politics has become more divided, with the media often caught in the crossfire. There was a brief uptick at the beginning of the COVID pandemic as the value of news became heightened for many users and trust levels have been largely stable since. In Finland and Norway trust levels were already high before the pandemic bump. Here, COVID also seems to have halted any declines, and trust has been maintained or improved since the pandemic.

What the media could do to increase trust

Whilst recognising that some of the reasons for low trust lie outside the control of many newsrooms (e.g. politicians stoking distrust), we asked survey respondents to give their views on areas the news media itself could improve. The top four themes are consistent across countries and also with previous research.12

1. Impartiality: The most frequently mentioned audience complaint relates to the perception that news media push their own agenda rather than presenting evidence in a balanced way. Many respondents say that journalists need to leave their personal feelings at the door. Avoiding loaded or sensationalist language was a repeated theme.

2. Accuracy and truth telling: Audiences would like journalists to focus on the facts, avoid speculation and hearsay, and to verify and fact-check stories before publishing. Fact-checking the false claims of others was another suggestion to improve the trust of a particular brand.

3. Transparency: Respondents would like to see more evidence for claims, including fuller disclosure of sources, and better transparency over funding and conflicts of interest. More prominent corrections when publications get things wrong would be appreciated, along with clearer and more distinct labelling around news and opinion.

4. Better reporting: Respondents wanted journalists to spend their time investigating powerful people and providing depth rather than chasing algorithms for clicks. Employing more beat reporters who were true specialists in their field was another suggestion for improving trust.

Impartiality, accuracy, transparency, and original reporting are what the public expects, even if many people think that the media continue to fall short. The good news is that these are things many journalists and news media would like to offer people. The challenge is that, especially in polarised societies, there is no clear common agreement on what these terms mean. Improving ‘truth telling’ for one group, for example, could end up alienating another. Adding ‘transparency’ features (see the example) can end up providing more information for hostile groups to take out of context or weaponise.

News avoidance and low interest in the news

Low trust and low engagement in the news are closely connected with ‘avoidance’, an increasing challenge in a high-choice news environment, where news is often upsetting in different ways. Across markets, four in ten (40%) say they sometimes or often avoid the news, up from 29% in 2017 and the joint highest figure we’ve ever recorded (along with 2024).

Avoidance is highest in Bulgaria (63%), Turkey (61%), Croatia (61%), and Greece (60%). It is lowest in Nordic countries as well as in Taiwan (21%) and Japan (11%).

In previous research we have identified two groups: 1) consistent avoiders that typically have low interest in news and low education, and 2) selective avoiders who struggle with news overload and look to protect themselves at certain times or for particular topics. This year we have asked again about the reasons for avoidance. These are many, interlinked, and are mostly consistent across countries.

Younger respondents are more likely to say that they feel powerless in the face of existential issues such as economic insecurity and climate change, that the news doesn’t feel relevant to their lives, or that it can lead to toxic arguments.

It is also striking that across countries under-35s are much more likely to say the news is too hard to follow or understand, suggesting that more could be done to make the news more accessible to younger and other hard-to-reach groups.

While the issues relating to wars, volatile politics, and economic gloom may be hard to change, the news industry is working on other ways to make news seem less depressing and more relevant. The Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet (SvD) has developed an app called Kompakt, with the tagline: ‘Read less, know more’, incorporating more visual and playful news formats and a button that allows you to filter out difficult stories when you are tired of the news.

Other publications are looking to broaden their news agenda through user-needs-based approaches (which we discussed in detail last year) – as well as investing in personality-led curated newsletters or podcasts with a lighter tone. The Globe and Mail in Canada has invested in new journalistic beats including a happiness reporter and a healthy living reporter. Constructive journalism looks to find hope and opportunities in long-running and difficult stories, while many publications have invested in text and video formats that explain complex stories in a concise way.

Meanwhile news organisations such as the BBC see greater ‘personalisation’ as part of the answer to news avoidance and declining engagement. They have announced plans to use artificial intelligence to better tailor news content for younger audiences.

Personalisation and the role of AI

The news industry has seen many false dawns with personalisation, partly because audiences worry about missing out on important stories, but also because they sometimes appreciate seeing things outside of their main interests. But with generative AI providing new capabilities to transform the format and style of stories, as well as making story selection more relevant, personalisation has become a hot topic again. In this year’s survey we asked respondents about their interest in eight different potential AI applications that could be used to better suit their individual needs.

We found the interest in AI personalisation to be highest when it comes to approaches that make news content quicker/easier to consume and more relevant, such as summarised versions of news articles (27%) and translations of news articles (24%).

More broadly, we find that interest in options for adjusting the format and style of news is higher than options for personalising the selection of stories, likely linked to those concerns about missing out. This is especially important because, so far, news media have used automation more for personalised selection than for changing the form of the content itself.

There is less interest in using chatbots to answer questions (18%), perhaps not surprising given that this functionality is still emerging, with the FT and the Washington Post amongst those trialling chatbot-like applications trained on their own content. Overall, while a relatively small proportion are interested in any single option, it is worth keeping in mind that a majority (66%) is interested in at least one of them. The public seems curious about and interested in how AI might help improve their experience of the news and the value it offers, even as they – perhaps like the industry – still do not know what this should look like.

Generally speaking, younger people tend to express higher levels of interest, especially when it comes to the personalisation of formats. It is likely that these differences are at least in part driven by young people’s greater familiarity with and higher comfort with AI. The Independent (UK) has recently launched a new service aimed at younger readers called ‘Bulletin’ which uses Google’s generative AI service Gemini to present its regular stories in five to ten bullet points.

We also find significant country differences, with interest in translation services highest in linguistically unique European countries with relatively small populations such as Finland, where consumption of news outside the country is relatively high. By contrast, the ability to adapt news text to different reading levels ranks highly in countries with lower literacy. In India, it is the most popular option.

For further analysis see How audiences think about news personalisation in the AI era

Artificial intelligence and the news

Looking at audience attitudes to generative AI more widely, we repeated questions this year around comfort levels for the two most common scenarios: (a) news content that is produced mainly by AI, albeit with some human oversight, and (b) mainly by humans with some help from AI.

Over the last year more journalists have been using generative AI in newsrooms to support their work via research, transcription, suggested headlines/summaries, and other purposes. We have also started to see more cases where AI is generating stories automatically. The UK’s largest regional publisher Reach, for example, employs an AI tool called Gutenbot to assist its journalists in rewriting stories for different websites within its network, while the German tabloid Express.de has used an AI bot called ‘Klara Indernach’ to author more than 1,500 stories, accounting for 10% of stories read.13

Audiences remain broadly sceptical of these automated approaches to news production, with similar scores to last year, but are more accepting of journalists using AI in a supportive role. As with last year’s data we find that younger groups – who are more likely to use AI chatbots regularly – are more comfortable than older groups. We also see more scepticism in Europe than in the United States, where big tech companies are investing heavily in these new technologies.

It is a similar picture elsewhere, though we find less scepticism in Asia where both audiences and publishers have shown less caution than in Europe or North America.

In Indonesia, the leading broadcaster TVOne uses AI-generated reporters to present content via its social media channels. Nong Marisa is an AI anchor in Thailand which presents the news on the Mono 29 TV channel. And several Indian newspapers have launched YouTube channels using high levels of automation and AI presentation.

![]()

Looking across countries we find a clear correlation between levels of comfort with automatically generated news and reported usage of AI chatbots. Almost a fifth (18%) of our Indian sample said they were using chatbots such as ChatGPT and Google Gemini to access news weekly, with comfort levels of 44%. By contrast, usage in the UK was just 3%, with comfort levels of just 11%. All this suggests that AI news is likely to develop faster and in potentially different ways in certain parts of the world, with media coverage and attitudes to technology playing an important role in shaping opinions.

Delving into the reasons for scepticism, we find that respondents feel generative AI is likely to make news more (rather than less) cheap to make (+29 net score) and more up-to-date (+16), potentially increasing challenges around overload/avoidance, even if some feel it could make the news easier to understand (+7). At the same time a significant proportion think that AI will make the news less transparent (-8), less accurate (-8), and less trustworthy (-18). Well-publicised cases where Gen AI technology has made factual errors, made up or misrepresented quotes or citations,14 may be feeding these concerns.

Whatever publishers do with Gen AI, it is the tools created and popularised by big tech companies that are likely to have the most impact with consumers, as they increasingly integrate real-time news content. Averaged across markets, just 4% say they have accessed the most popular tool ChatGPT for news in the last week, with lower scores for rival services from Google, Meta, Microsoft, and others. The low score for Google’s AI Overviews is perhaps surprising given its prominence at the top of search results, but it is important to remember that audiences may not be aware that answers are being generated by AI and the tech giant has also been cautious about using the feature around news queries so far.

AI-driven aggregators increase their reach

One further area to watch is the growing importance of online and mobile aggregators that already play a dominant role in countries like Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia. Many of these now use Gen AI technologies to personalise the selection of news content, in the same way TikTok has done for user-generated content. One example in the United States is Newsbreak, a fast-growing app which has 9% weekly reach for its blend of national and international stories. Opera News, another personalised news app, is an important source of news in Kenya (38% weekly reach) and South Africa (14%).

Apple News, which reaches 14% weekly in the US and 9% in the UK, has also deployed Gen AI to summarise news alerts, though it later had to withdraw the feature after well-publicised inaccuracies.15 Gen AI apps such as Perplexity are developing news alerts and other personalised features, while Google surfaces personalised news selections as part of its main app or when you swipe right on an Android phone. These links, known within the industry as ‘Google Discover’, are accessed by 27% across markets but more in countries with a high proportion of Android phones in Latin America and Africa – though the embedded nature of these services makes it hard to produce accurate numbers through surveys.

Our research this year also shows how mobile notifications from aggregators, often driven by AI, are now one of the main ways of getting breaking news. This is especially the case in mobile-majority countries in Africa and Asia, such as Kenya and India. By contrast, in the UK and other parts of Northern Europe strong brands are in a better position to connect directly to consumers.

In the UK, notifications from the BBC News app, for example, reach almost half (46%) of those that receive alerts, the equivalent of around 4 million people – making it one of their most important channels for digital communication. At the same time publishers must be careful not to overload consumers, a significant proportion of whom (79%), across markets, either have never received alerts or have actively disabled them because they say they get too many or they are not relevant to their lives.

The smartphone deepens its hold on our time

Although the smartphone has been around for almost 20 years, there is no sign that its impact is diminishing. And this in turn continues to drive changes to how we access the news and the formats we use to consume it. One way of understanding this is with a question we ask about the first device people come across in the morning.

This gives us a picture of habits at a crucial point when people have traditionally looked to brief themselves for the day ahead. Taking the UK and the United States as examples, we see how radio and television have been eclipsed by the convenience of these powerful personal devices.

In the United States, shows like Good Morning America have lost around half their audience in the last decade as smartphones have become more ubiquitous, according to industry data16. This shift, which has been accompanied by an increase in platform power, has encouraged more personalised news consumption as well as the growing popularity of podcasts and online video.

Although the smartphone plays a much bigger role than it did in every market, we do see significant and surprising differences. TV news remains the most important starting point in Portugal and Japan, while in Ireland, Denmark, and South Africa radio news is a key part of the mix. Meanwhile, more than one in ten (11%) Austrians still start their day with a printed newspaper, even if most of them are over 45.

The age splits are also revealing because they show how much legacy formats such as TV, radio, and print, now depend on over-55s. Everyone else is not just digital-first but smartphone-first. Even within top news organisations conversations still focus around the front page of the website, with formats optimised for reading long text, but that is no longer how most people want to consume the news. The shift to smartphone as the anchor device, which has gone hand in hand with the rise of communication apps, has also made it harder for any individual publisher app to cut through.

When we ask audiences how they access news on a smartphone over time, again we see the growing importance of social media, mobile notifications, and aggregators.

Paying for online news and the role of bundling

Changing device use and the growing power and changing strategies of big tech platforms are making it harder than ever for publishers to build sustainable businesses. In recent years a key response has been to reduce dependence on advertising – where big platforms take much of the available revenue – and build direct reader payment models instead. MailOnline is one scale-based publisher that has recently added a premium subscription layer, and broadcasters CNN and Sky News have announced plans to invest in exclusive online video (and audio) programming for which they plan to charge over time. But despite this, our data continue to show that the vast majority of audiences remain unwilling to pay for online news.

Across a basket of 20 countries where a significant number of publishers are pushing digital subscriptions, less than a fifth (18%) have paid in the last year via an online subscription, membership, donation, or one-off payment. Payment levels are highest in smaller European markets where publishers have a strong market position and platforms have traditionally played a smaller role, such as Norway (42%) and Sweden (31%) as well as Australia (22%) and the United States (20%). In other large markets, such as Germany (13%), Japan (10%), and the UK (10%), however, it is proving hard to persuade more than a small minority to pay and that task is harder still in many parts of Eastern and Southern Europe where only a small number of publishers ask for payment (e.g. Serbia and Greece 7%, and Croatia 6%).

Over the last ten years ongoing subscription levels across our basket of 20 countries have more than doubled but they now look to have hit a ceiling. Publishers have already signed up many of those prepared to pay and in a tight economic climate it has been hard to persuade others to do the same. In most countries, we continue to see a ‘winner takes most’ market, with upmarket national newspapers scooping up a big proportion of users. In the United States, for example, the New York Times has extended its lead over the Washington Post partly off the back of its highly successful all-access subscription that includes games, recipes, audio sport, and product reviews.

In Germany, local and regional news titles perform relatively well in terms of subscription, a reflection of the importance of regional identity in this federal system. Consumers in Nordic countries and the Netherlands are also more likely than the average to pay for a regional or local online news service, but in the United Kingdom and Portugal payment is mostly confined to national titles. Meanwhile, in Canada and Ireland around half of subscribers (50% and 59% respectively) pay for a news service originating outside the country, leading to an even tougher market for domestic publishers.

In some markets, some publishers that own both national and local titles have been marketing bundled ‘all access’ subscriptions: +Alt from Amedia now reaches 16% of Norwegian subscribers (+6 points more than last year) with Schibsted’s Full tilgang (All access) package reaching 8%.

Alternative versions of these bundles include magazines, premium podcasts, and even international titles. At the same time publishers have been building new lifestyle products such as games and cooking as a way of building habit and reducing churn. Others such as the Washington Post and a number of European publications have been experimenting with cheaper or more flexible ways to pay, such as day passes or more limited propositions aimed at younger readers.

Around a fifth of survey respondents who are not currently paying in the United States (21%) and Germany (19%) said they might be interested in one of these options, especially the possibility of accessing multiple news providers for a reasonable price. But in all countries the vast majority say that none of these ideas could persuade them to pay.

These data suggest that it may be possible over time to get more customers to pay for news, even in countries where payment levels are already high. Innovative product development will be key but the challenge for publishers will be building more flexibility and value for different groups without reducing the core editorial proposition – or the average price paid by existing customers.

Local news under pressure

While many upmarket national newspapers can now see a path to profitability through a mix of digital subscription and diversified revenue streams, there are deepening concerns about the future of local news. In the United States and much of Europe, local and regional newspapers have struggled to adapt to the shift to digital while consumers have found more efficient ways of getting services they once provided.

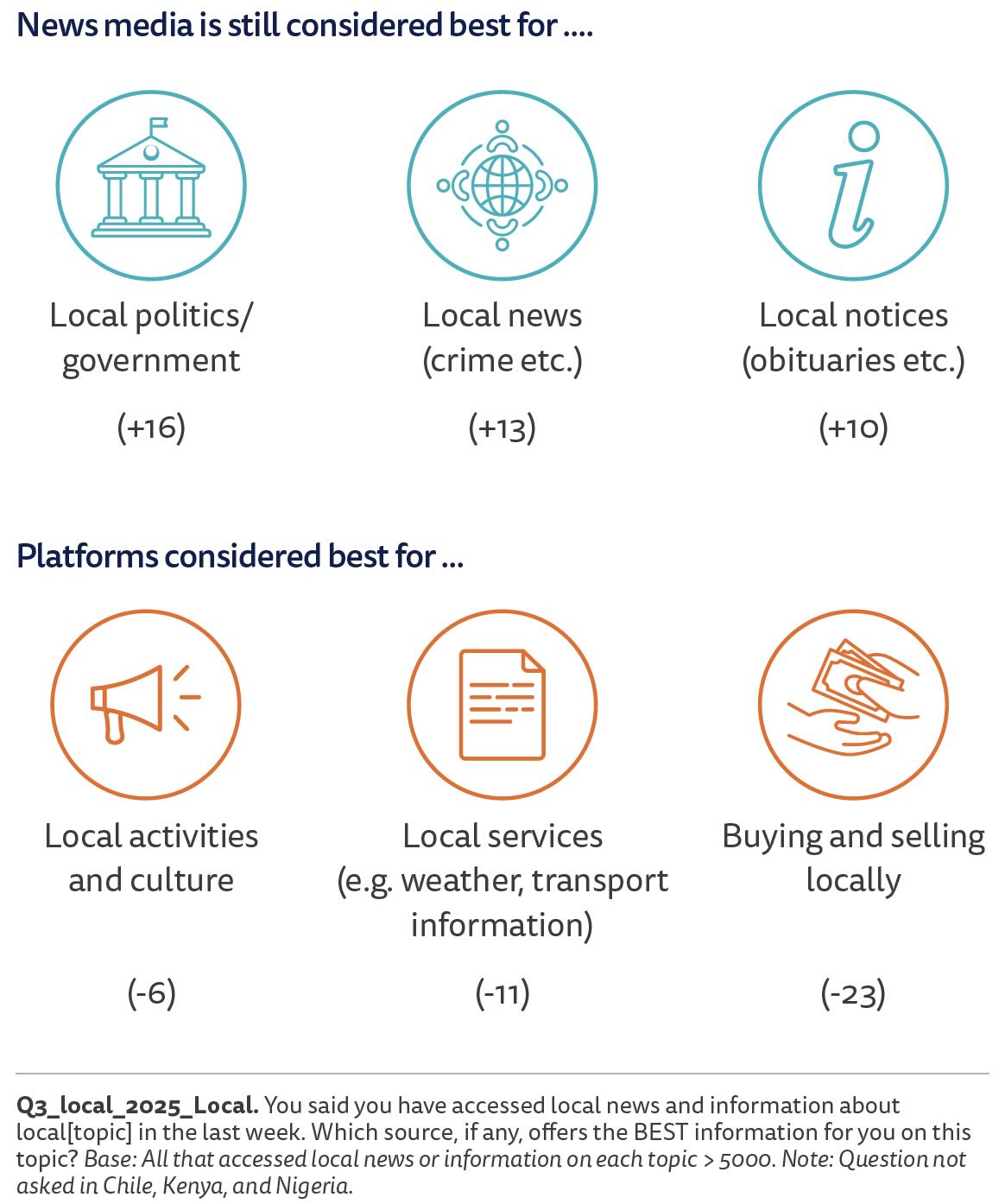

Our report this year shows the extent of this challenge. Although people repeatedly say in surveys that they are interested in local news, we find that most people across markets think news media (local television, newspapers, and radio) are only the best source of news for local politics, local news stories, including crime and traffic accidents, and notices (such as the obituaries of local people). Platforms or specialist apps tend to be seen as a better source for local activities, culture, information about local transport or weather, and buying and selling – all of which used to be dominated by local news media. This is part of the reason local media are struggling in many countries, and why models such as bundling and aggregation offer a potentially more hopeful path.

Net difference between proportion who think news media is best source and those that think platforms are best source

Conclusions

Over the last decade our report has documented how mobile devices and powerful tech platforms have upended the news industry, changing the content people see, the way news is presented, and the business models of leading publishers. Now the challenges for institutional journalism are intensifying in the form of a platform-enabled alternative media ecosystem, including podcasters and YouTubers, that is proving engaging both for audiences – and also for politicians, many of whom no longer feel they need to submit themselves to journalistic scrutiny. The growth of video-based networks like YouTube and TikTok, highlighted again in this year’s report, is encouraging the trend towards personality-led commentary, much of which is partisan, and which many worry is squeezing out facts and making it harder to separate truth from falsehood.

And yet in many countries where press freedom is constrained, these same trends sometimes also offer hope for greater diversity of expression and for alternative views to find a voice. Elsewhere still, creators and influencers are showcasing innovative and authentic ways to tell stories and build community in powerful new ways. These approaches have much to teach legacy media about how to re-engage with younger and hard-to-reach audiences and to combat selective news avoidance and news fatigue.

Everywhere there are common challenges around the pace of change and how to adapt to a digital environment that seems to become more complex and fragmented every year. Increasing the uncertainty is the emergence of generative AI as a source of news for the first time – as tech companies rapidly embed this into their core services – with younger people in particular using it both for getting the news and also for checking facts. We already find much higher use of Gen AI in parts of Asia and Africa, where comfort with these technologies around news is already much higher than in Europe, where audiences remain mostly sceptical. In turn this is affecting the speed at which publishers feel they can innovate and change. Publishers are looking to use AI technologies to increase efficiency but also improve the relevance of content through personalising story selection and formats. None of this provides a silver bullet but will be part of a wider toolkit that news organisations hope will enable them to rebuild connection and provide greater value. In this respect, some publishers are thinking radically about bundling news with lifestyle content, repackaging different titles and formats, or licensing content to AI platforms, but many others continue to struggle to convince people that their news is worth paying attention to, let alone paying for.

The danger is that publishers will use automation to cut costs and chase new AI algorithms. Some of that is already happening but it is clear that people don’t want more content. They already feel overloaded. They certainly don’t want sensationalist headlines optimised for AI aggregators. Our report is very clear that, across countries, audiences expect the news media to be more impartial, more accurate, more transparent, and critically to increase the amount and quality of their original reporting. Trusted news brands remain the first choice for many when it comes to checking information, or alerting them to important breaking news, even if people don’t need them as often as they once did. It is also striking that advances in AI come at a time when human connection seems more important than ever, in terms of other trends highlighted in this report such as personality-led news. The task for publishers is how to adjust to these new realities, to embrace technology where it makes sense while keeping humans in the loop – and to make the news more engaging and personal without losing sight of the values that attract people to their brands in the first place.

Footnotes

1 https://www.theguardian.com/media/2024/nov/13/why-the-guardian-is-no-longer-posting-on-x

2 https://techsabado.com/2024/08/28/social-media-x-formerly-twitter-engagement-rate-drops-almost-40/

3 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cy7kpvndyyxo

4 https://www.inma.org/best-practice/Best-Use-of-Social-Media/2025-546/VGs-Social-Media-Amplification-of-Investigative-Journalism

5 https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2025.pdf

6 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c9814k2jlxko

7 https://factcheck.afp.com/doc.afp.com.364Z8FB

8 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-57831201

9 ‘GenZ: Trends, Truth and Trust’, Channel 4 research, Jan. 2025.

10 https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/alerts/President-Trumps-Freedom-of-Speech-Order-Takes-Aim-at-Social-Media-Broadcasters

11 https://www.ofcom.org.uk/online-safety/illegal-and-harmful-content/time-for-tech-firms-to-act-uk-online-safety-regulation-comes-into-force/

12 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/trust-news-project

13 https://www.linkedin.com/posts/schultzhomberg_kstamedien-artificialintelligence-klaraindernach-activity-7185555200818970624-C1vd/

14 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cq5ggew08eyo and https://www.bbc.com/mediacentre/2025/bbc-research-shows-issues-with-answers-from-artificial-intelligence-assistants

15 Apple Suspends Error-Strewn AI Generated Alerts, BBC, 16 January 2025.

16 Around 2.6m watched GMA in March 2024 compared with 5.1m in April 2015. ABC News, 16 April 2025.