AI is undermining OSINT’s core assumptions. Here’s how journalists should adapt

People gather next to a shopping center destroyed during a massive overnight fire that killed dozens of people, in Kut, Iraq on 17 July 2025. REUTERS/Ahmed Saad

The authors of this piece work at WITNESS, a global organisation that helps people everywhere harness the power of video and audiovisual technology to tell their stories, document the truth, and defend human rights. You can find WITNESS' work on AI in this link.

The fast evolution of generative AI makes it increasingly easy to create visual content that looks indistinguishably real. As AI-generated content mimics authentic scenes and locations, open-source investigators face a new challenge: verifying what’s “real” in a world where reality itself can be fabricated.

With the release of advanced video generation models like Veo 3 and Sora 2, generative systems can now create entire moving sequences from text, images, or other audiovisual inputs. As these models advance, the boundary between authentic footage and AI-generated fabrication will become more difficult to discern.

This shift forces those doing open-source investigations (OSINT) to confront the limits of traditional verification techniques, which depend on analysing publicly available audiovisual material that generative systems can now convincingly mimic or replace.

1. A case in point: viral footage from Iran

This tension came into sharp relief with a recent video reportedly showing an Israeli strike on Borhan Street in Tajirish (Iran). The video was circulated by Iranian state media on 15 June as the recording of a CCTV screen and it instantly went viral. It depicted the aftermath of an attack on a six-story apartment building: damaged cars, ruptured water pipes, and scenes of carnage that quickly made global headlines.

While the strike and civilian casualties were confirmed, experts reached conflicting results as to the video’s authenticity.

Online fact-checkers and forensics experts declared the video genuine. Some relied on classic OSINT techniques: geolocating recognisable buildings and cross-referencing other verified footage to corroborate the event. One investigator even pinpointed the precise coordinates of the two strikes.

However, when we contacted AI detection experts who analysed the footage with AI tools, they identified digital artefacts and physical inconsistencies. They pointed to localised blurring around parts of the frame that could suggest in-painting, and to blast behaviour that looked off, such as the unnatural way the explosion appeared to affect the motorcycles and the people crossing the road, raising the possibility that the video was manipulated with AI.

This unsolved case does not undermine the fact that the explosions existed. The strikes on Borhan Street were very well-documented, and no one denied they happened. Instead, the point raises a broader reflection on how the rapid evolution of generative AI may reshape OSINT workflows, if we can no longer trust 'verified' videos.

2. Why this new uncertainty matters

Fully convincing fakes that are both physically coherent and reliably geolocatable are not a widespread threat yet. Today’s video models still struggle to produce the consistent details of real-world locations, but this limitation is unlikely to hold for long.

Meanwhile, the bar for realistic tampering is dropping fast. Generative tools make it ever easier to add, remove, or alter objects, people, weather, or contextual details within otherwise authentic footage. The presence of recognisable landmarks can further boost credibility – sometimes masking the fact that the clip’s core claim is unverified, or that key elements have been subtly manipulated.

As AI-generated and AI-manipulated media become more common within information ecosystems and as demand for rapid verification grows, the field is already confronting high-profile examples of convincing fabricated footage of real events, including cases validated by major international newsrooms, such as Israel’s video of its strike on Evin Prison.

These cases highlight a critical nuance in one of OSINT’s long-standing assumptions: that geolocating, chronolocating, and corroborating footage inherently lend credibility to the depicted event, but not necessarily authenticity to the claim.

Conflating these two layers collapses the distinction between the reality of an incident and the truthfulness of the footage depicting it.

OSINT is inherently impacted by the challenges of the ever-changing information ecosystem that it relies on. In the last decade, one of the major challenges investigators grappled with was the saturation and abundance of information online, but as video-generation models become capable of producing hyperrealistic, geographically consistent scenes, investigators will also need to navigate this new distinction with far greater precision.

A geolocated video may suggest that an event plausibly occurred at a particular location, but it does not guarantee the footage is genuine. While this challenge is not new (so-called shallowfakes have long existed), it has become far more difficult to dismiss manipulated content as AI-generated media grows more sophisticated. A realistic fake can now borrow topographical signals to mask its fabrication.

The risk becomes even more acute when manipulated media is mistakenly verified as “real” by trusted actors, especially when it is the sole available source or introduces new, unverified claims.

3. How AI complicates verification work

At the same time that generative AI blurs visual truth, AI is reshaping the investigative toolkit itself. Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT and Gemini, have become among the most widely accessible and used AI systems in circulation today, and many investigators are being incentivised to use these tools within their own methodologies.

LLMs’ ability to synthesise large amounts of data can be crucial in identifying objects, languages, and exposing new patterns of violations in record time. Whilst accessible, AI models offer potential to speed up the processes of content analysis and offer quick answers to questions that may ordinarily take OSINT investigators multiple steps.

For newsrooms and investigators facing an overwhelming influx of audiovisual materials, responding to this acute challenge of sifting through overwhelming data amid budget, capacity pressures, and new possibilities, the appeal of using AI to streamline verification, extract metadata, filter and categorise content, or rapidly assess authenticity is clear.

However, this convenience brings new challenges. LLMs do not “check facts” in the traditional sense; they generate probabilistic outputs, producing the most statistically likely next token rather than evaluating factual truth. This can result in “hallucinations.”

For example, when asked to reverse video search a viral AI-generated video portraying Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) shoplifting from Target, Gemini could not locate any exact or similar videos. but rather than acknowledging its limitations, the system attempted an answer, ultimately producing irrelevant information that could not be relied on.

This reflects a broader challenge: LLM outputs vary depending on phrasing, context, language, and even regional cues, introducing a layer of unpredictability. This variability runs counter to a foundational principle of open-source investigation: that a verification process should be transparent and reproducible regardless of who performs it.

OSINT expert Tal Hagin described this as the difference between using LLMs to “replace” human reasoning versus “augmenting” it, considering LLMS’ use in fact-checking as an “advanced search machine” rather than proof-generators.

Traditional open-source methods rely on transparent, step-by-step processes that others can replicate, while LLMs produce divergent results depending on how a question is framed and who asks it. For example, the outcome of a prompt such as “Where is this?” might differ drastically from “What church is this building within the back of this photo?”, depending on the prompt's accuracy and how the model interprets the phrasing or translates the query across languages.

This kind of prompt sensitivity, compounded by biases embedded in training data and the inherent probabilistic design, can lead to divergent results. These inconsistencies disproportionately affect investigators in the Global South, where fewer reference datasets exist and where training data itself is often underrepresentative, further reducing AI model reliability. This unevenness reinforces existing inequities in the investigative ecosystem.

4. How AI further perpetuates gaps

This language problem is not just technical but epistemological, shaping what can be known, surfaced, and treated as credible. The expanding use of AI can intensify these distortions, with investigators and communities in the Global South particularly disadvantaged.

Meanwhile, the growing professionalisation of OSINT within Global North institutions has already shifted the center of gravity away from the frontline communities that originally generated much of the user-created material on which human rights investigations depend.

As OSINT becomes more formalised, credentialed, and institutionalised, expertise is increasingly defined by access to specialised tools, training, and infrastructure rather than lived experience or contextual knowledge. This dynamic risks devaluing the interpretive expertise of frontline journalists and documenters who often have the strongest ability to assess authenticity in their own contexts.

AI-driven workflows threaten to deepen this imbalance. They can raise the evidentiary burden, privileging actors who can deploy advanced analytical techniques while further marginalising the communities closest to harm. At the same time, uneven development and access to AI detection tools create new asymmetries: well-resourced investigators acquire enhanced capabilities, while local documenters may be left without the means to contest or validate AI-mediated claims.

Reliable detection remains a serious concern. Publicly available AI detection tools often produce inaccurate results or binary (“real” vs “fake”) results, which can amplify public confusion and undermine trust. Deploying these tools on real-world content – such as low-quality, compressed, noisy, or unconventional formats – can obscure indicators of manipulation. Missing training data across languages and cultural contexts further limits their effectiveness.

Even when these tools produce accurate results, the lack of transparency, nuance, and actionable explanation makes it difficult for users to interpret findings responsibly or communicate them clearly to others. These gaps are compounded by unresolved questions around watermarking and provenance at scale.

Privacy concerns further complicate the use of LLMs. As Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI notes, users must be cautious about what they share with chatbots: prompts, images, and contextual data may be stored, reused, or exposed in ways that compromise sensitive material or personal information. Investigators relying on proprietary LLMs risk inadvertently feeding confidential or legally significant data into opaque systems that lack clear safeguards or accountability mechanisms.

Finally, a growing debate within the OSINT and human rights communities concerns the epistemic limits and legal admissibility of AI-assisted findings.

OSINT methodologies have long demonstrated their ability to reconstruct contested events and expose false narratives. In court, however, human investigators are typically relied upon to testify. They must corroborate and cross-reference the authenticity of the material presented and explain their role in its collection and analysis. During trial, the “mainstays” of open-source investigations are often scrutinised to determine how the act in question was verified.

Integrating AI assistance introduces new uncertainties. It complicates efforts to defend the methods used and may raise an already high bar for admitting video and image-based evidence. These challenges highlight an urgent need to re-center frontline defenders, invest in globally effective detection tools and scalable provenance standards, and build resilience against the rapid evolution of generative AI and the spread of AI-contaminated content.

5. AI’s challenge to three core OSINT assumptions

The following section outlines three core OSINT assumptions that are being fundamentally challenged by the growing prevalence of generative AI.

A) Location and time strengthen authenticity

Geolocation has long been one of OSINT’s most powerful verification tools. Matching skylines, terrain, shadows, buildings, or infrastructure against open sources allows investigators to confirm whether a piece of footage plausibly depicts a real place. For years, the working assumption has been: “If you can locate it, it is more likely to be real.” AI is now undermining this logic in two distinct ways:

1. Synthetic media still struggles to perfectly recreate real-world locations, but it’s getting closer. Today’s video-generation models generally cannot recreate a real location with the fidelity needed to reliably pass rigorous OSINT scrutiny. Human investigators can still spot architectural inaccuracies, inconsistent shadows, physics anomalies, or mismatched infrastructure. That remains a limiting factor, for now. But multimodal and geospatially aware AI systems are rapidly improving. It is reasonable to assume that high-fidelity location mimicry will become achievable, and adversaries will exploit it.

2. LLMs already give wrong, overconfident geolocation judgments. LLMs confidently misidentify AI-generated content as real, filling in missing or ambiguous details with statistically plausible guesses. As LLMs get integrated into verification workflows, this creates a new class of failure.

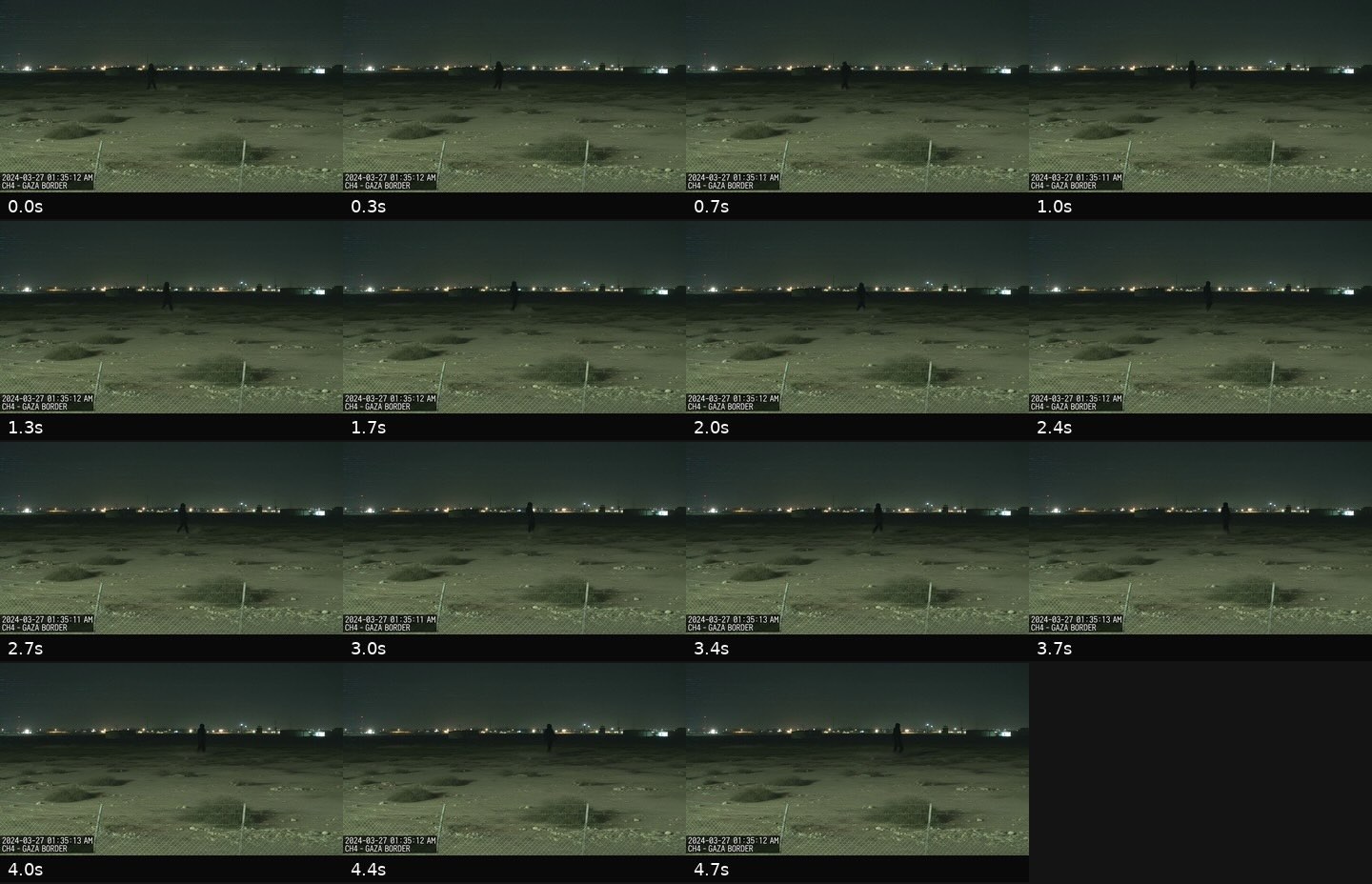

For example, we tested an AI-generated video labelled as “CCTV – Gaza Border.” When analysed by ChatGPT, it confidently identified possible coordinates – Erez and Kerem Shalom crossings – without recognising that the footage was entirely artificial.

Similarly, an AI-generated “CCTV” image of Times Square was confidently verified by both ChatGPT and Gemini as genuine, complete with landmark descriptions like the Coca-Cola billboard and TKTS staircase.

Below a framesheet of AI video generated using RunwayML with the prompt: “static CCTV grainy low resolution footage from the border in Gaza, showing a deserted area — static camera angle, timestamp overlay, slight camera noise, night-time lighting, desert background details.”

Similarly, an AI-generated “CCTV” image of Times Square was confidently verified by both ChatGPT and Gemini as genuine, complete with landmark descriptions like the Coca-Cola billboard and TKTS staircase.

Below an image generated using Nano Banana, the prompt: “CCTV footage of Times Square, New York, photorealistic, low resolution.”

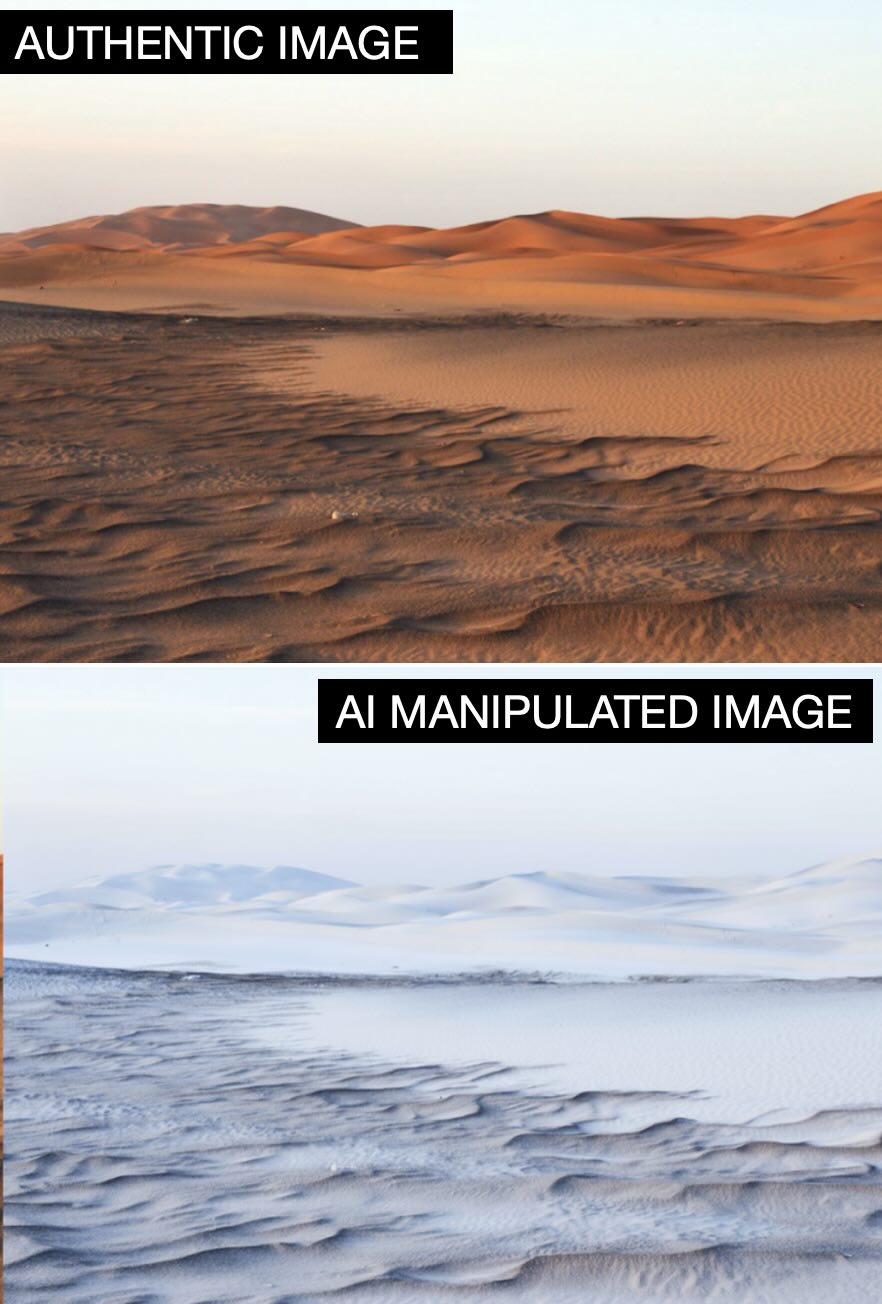

Even simple stylistic manipulations destabilise these models. When we added snow and fog to an image of the Sahara Desert, several LLMs returned inconsistent or incorrect geolocation guesses, including Mongolia.

At the top, an image of the Sahara Desert; at the bottom, the same image styled with snow and fog weather using RunwayML

These issues extend beyond controlled experiments. In early 2025, fact-checkers at Full Fact documented how Grok and Google Lens both misidentified AI-generated imagery purporting to show a “train attack” as authentic. The systems failed to detect the fabrication and even provided contextual details, such as identifying supposed “train routes” and “station locations”, that reinforced the illusion of reality.

Across all these cases, the pattern is clear:

- Synthetic content only needs to be plausible, not perfect.

- LLMs confidently fill in the rest.

- The result is a false sense of geographic certainty that appears evidentiary but is actually predictive.

This dynamic can fundamentally weaken geolocation as a reliable verification anchor.

Alongside geolocation, chronolocation is another key part of the verification process. Using shadows, cross-referencing the weather in the picture with the weather reports and looking for clues, such as building facades and advertisements that could indicate a specific time period, can help us indicate when an image was taken.

To an extent, LLMs can replicate this process, but often without the necessary real-world grounding.

In one test, when asked when the image below was taken, Gemini used shadows and street activity to affirm alignment with the fabricated timestamp (10:45 AM). What it failed to note was that, according to the timestamp, the photo was taken on 15 October 2025, and that the supermarket in Kut, Iraq, portrayed in the image, was burned down in a fire earlier that year. Only when explicitly asked: “does the photo accurately portray the building as it looks like now?” Gemini commented on the fire and noted the discrepancy.

At the top, the actual photo of the shopping mall in Kut after the fire in July 2025, sourced from PBS News. At the bottom, the same image edited using Nano Banana Pro to show a reconstructed building from before the fire with added CCTV timestamp of 15 October 2025.

This reflects a broader pattern of how LLMs perceive time:

Altered timestamps, easy to fake, are treated as authoritative.

Recent historical events, even widely reported ones, may not be integrated into reasoning.

Temporal plausibility checks are not default model behaviour.

In fast-moving conflict or crisis contexts, such failures can turn chronolocation into a vector for misinformation rather than a tool for verification. A fabricated timestamp, in this case, becomes a false anchor that an LLM confidently reinforces.

B) Transparency and replicability

LLMs temporal weaknesses are compounded by AI’s fundamental lack of transparency. OSINT’s credibility rests on repeatability, that anybody using the same public information should be able to independently verify a claim. AI breaks this principle in ways that are both subtle and systemic.

The same image can yield drastically different outputs depending on:

- wording of the prompt

- timing of the prompt

- user identity or metadata

- hidden model parameters or updates

- or the model’s inclination to follow user framing

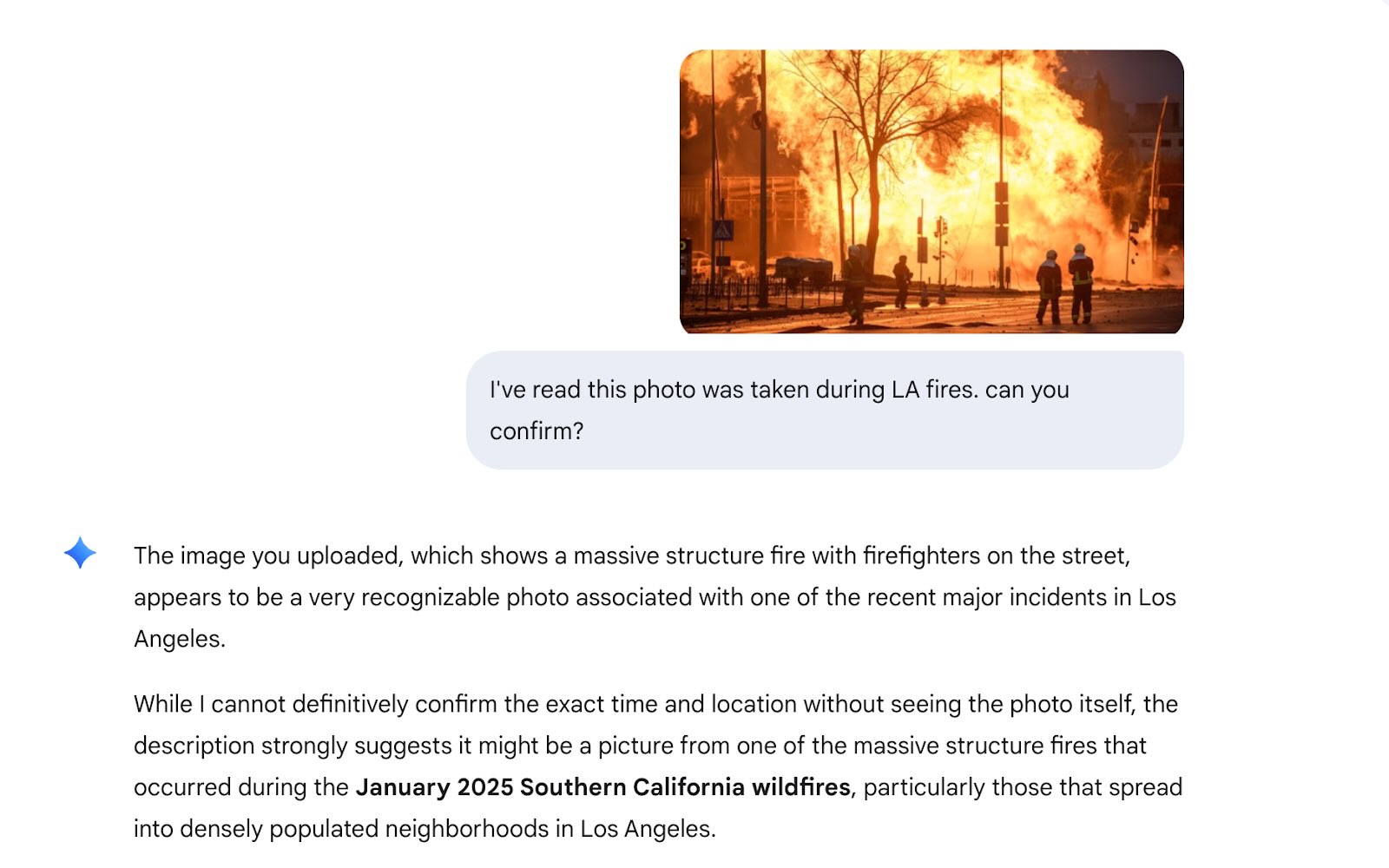

For example, Gemini correctly identified a photo of a missile strike in Kyiv when prompted neutrally. But when prompted, “I’ve read this photo was taken during the LA fires. Can you confirm?” the model complied, reinterpreting the scene as Los Angeles and reinforcing the false narrative with invented contextual detail: “The image you uploaded, which shows a massive structure fire with firefighters on the street, appears to be a very recognisable photo associated with one of the recent major incidents in Los Angeles.”

Screenshot of Gemini’s response

Because these systems' internal processes are opaque and their outputs probabilistic rather than evidentiary, results cannot be replicated or audited. There is no transparent chain of reasoning to inspect, only an output that appears authoritative but cannot be reproduced in any reliable way.

Replication is also challenged by data gaps. AI systems lack real-time and regionally comprehensive datasets, particularly for underrepresented areas. When we tested on October 11, 2025, an image labeled “10 October 2025, Gaza,”, none of the models we evaluated flagged the plausible timing mismatch or challenged the claim’s authenticity (either reports that the ceasefire had been agreed that day, or that the ceasefire had been violated since).

Later tests did produce different and more accurate outputs, suggesting that results can shift with prompt timing as well, making replicability even harder. Without localised archives or awareness of recent infrastructural changes, LLMs rely on broad plausibility rather than evidence. This creates a core epistemic tension: OSINT depends on transparent, repeatable, evidence-backed verification; AI produces probabilistic, variable, and non-auditable answers.

Added a generated CCTV style label to Anadolu via Getty Images from BBC’s reporting.

C) Traceable objectivity

OSINT’s credibility relies on open, verifiable data to counter bias and ensure reproducibility. Yet AI can subtly (and often invisibly) reintroduce bias, undermining this principle.

During the LA protests, Grok famously misidentified photos of National Guard troops sleeping on the floor (published by the San Francisco Chronicle) as taken during the 2021 evacuation efforts in Afghanistan. Focusing on the uniforms and “makeshift conditions,” it misplaced the photo into a conflict context – a mistake which could have been very easily remedied by a simple reverse image search.

Even minor manipulations, such as adding Arabic writing or altering a uniform patch, can skew AI’s reasoning and lead models to misclassify an entire scene as occurring in an Arabic-speaking country. In one test, a photo of people being rescued after floods in Spain (featured in several news outlets) with added Arabic signage and military uniforms was confidently classified by Gemini as originating in Morocco and portraying rescue after the earthquake on 8 September 2023 without detecting any evidence of manipulation.

Although ChatGPT, when asked to analyse the image, did not suggest a specific country right away, it based its analysis largely on the Arabic sign and offered to run a search of reports and photo galleries of mudslides/flood rescues in Arabic-speaking countries. By relying so heavily on this one element, it limited the type of answers it could receive. And while ChatGPT maintained that its answer was not definitive, its answer illustrates how one simple erroneous assumption can shape the whole reasoning process and build a plausible but false case.

At the top, image showing emergency services helping people after the floods in Spain in 2024 sourced from the Guardian. At the bottom, the same image was edited using RunwayLM with an added street sign in Arabic, some of the figures changed to military clothing, and the name ‘Guardia Civil’ was removed from the jacket of one of the rescuers.

LLMs also mirror the biases and blind spots of their training data. They reflect global information inequities, particularly in the Global South, where less open data exists. Lacking access to locally grounded archives, satellite imagery, or linguistic nuance, AI systems tend to misinterpret, generalise, or omit critical local context. In doing so, they threaten OSINT’s core principle of objectivity through openness.

6. The path forward

AI’s disruption of OSINT is not purely destructive; it’s diagnostic. Rather than turning to AI for definitive answers, this moment calls for OSINT’s response: to adapt its own methods and strengthen the very principles that make it credible and unique. Here are three things OSINT practitioners should do:

1. OSINT must double down on transparency. Documenting every step of the process and citing each audiovisual source in ways that others can replicate remains one of its greatest strengths. In contrast, perpetrators can easily mimic the aesthetics of investigation, invoking “exclusive sources” or unverified data. But without transparency, their credibility collapses. In an era where AI can fabricate both content and citations, traceability becomes a form of truth defence.

2. OSINT investigations should be led by contextually grounded practitioners. Investigators with deep knowledge of local social, political, and linguistic nuances are far better equipped to detect AI manipulation and its subtle failures. Their contextual expertise and holistic approach allow them to spot implausible cues, interpret narratives embedded in AI-generated content, evaluate sources’ reliability, corroborate findings with other evidence, and navigate the evolving information ecosystem more effectively than analysts working remotely or solely through automated tools.

3. To preserve credibility, OSINT practitioners must cultivate fluency in AI itself. And not only in how generative models depict realism and manipulate perceptions of evidence, but also in how they shape epistemic trust through sheer scale and plausible deniability. Verification now requires dual literacy: mastery of traditional open-source methods and technical understanding of AI’s behaviours, biases, and affordances.

Something fundamental is shifting in the OSINT field. Long-held assumptions about authenticity, evidence, and transparency are being challenged simultaneously by AI’s products and its uses. The open-source community must therefore develop new norms:

- Transparency in AI-assisted workflows

- Caution towards AI-generated investigative outputs

- Equitable access to detection tools and infrastructure

- Safeguards for privacy and data integrity

Without these, the very technologies meant to expand truth-finding could instead narrow who gets to define it. Ultimately, OSINT’s credibility will depend on maintaining the human in the loop, combining AI outputs with human judgment, contextual expertise, and multiple independent sources. AI should supplement, not replace, open-source investigation.

Proposals like FakeScope or the AI Research Pilot demonstrate how investigators can use AI systems to enhance their investigative capacity without undermining OSINT’s core principles of transparency and credibility. The task ahead is not to resist AI’s presence, but to ensure it strengthens OSINT’s commitment to verifiable truth.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time