In this piece

Snow White Mirror Syndrome: protecting editorial values in a reader revenue model

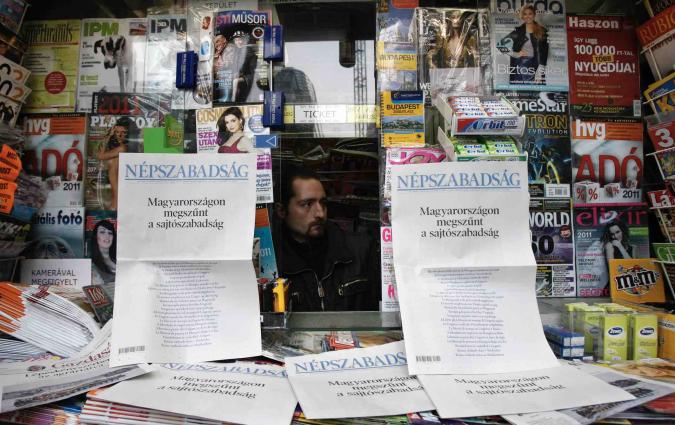

Ignacio Escolar, the editor and founder of Spanish newspaper 'elDiario.es', describes readers who protest any coverage that contradicts their values as having "Snow White Mirror Syndrome". | REUTERS/Laszlo Balogh

In this piece

In praise of the reader revenue model | Old values in a new reality | Indirect pressure: data | Direct pressure | A final word on OpinionAs winter’s frost retreated from Ukraine in mid-April of 2022, a temporary slowing of the Russian invasion allowed journalists on the ground to report on the atrocities of the war in better detail. Dozens of reporters risked their lives to independently document events and shed light on what’s happening there. Among them: elDiario.es’s team.

The Spanish news outlet offered its readers first-hand information from Ukraine and opinion columns about the invasion. But their coverage produced recurring “editorial friction” between the newspaper and a section of its audience. Part of elDiario.es’s community of readers were unhappy the outlet didn’t blame NATO for the invasion.

They wanted the outlet that they pay membership fees for – elDiario.es’s business model since its foundation in 2012 – to twist its coverage, and some threatened to withdraw their support if it did not.

The editor-in-chief of elDiario.es, Ignacio Escolar, calls this ‘Snow White Mirror Syndrome’: readers who are incapable of processing information that challenges their worldview and only want journalism that backs up their outlook. He said he is used to this kind of pressure and not willing to cave to such demands. The media outlet he founded with his colleagues will continue to practise independent journalism – it does not exist to reinforce ideas and preconceptions but to speak the truth, he said.

In praise of the reader revenue model

Journalism has endured harsh years: newspaper advertising revenues decreased by almost half in the 10-year period preceding 2019, and COVID-19 dealt a further contraction of revenue by 25% in 2020.

Pushed by the need for new income sources, some media bosses have finally opened the door to innovation. There are now several organisations – in multiple countries and with diverse content offerings – practising independent journalism and proving reader revenue models can deliver reliable results.

Of newsroom leaders surveyed in the Journalism, Media, and Technology Trends and Predictions 2022 report, 79% said a subscription or membership strategy was their most important revenue priority, ahead of both display and native advertising.

But as more news outlets turn to reader revenue models, what systems are in place to ensure that editorial impartiality is safeguarded from the influence of those who fund it? What lessons can we take from pioneers in this field?

This essay aims to capture key insights from leaders in reader-funded newsrooms – the Financial Times (FT), El País de Madrid, elDiario.es, Dennik N and 444.hu – about how they deal with indirect reader pressure (from data) and direct reader pressure (through feedback and cancellations).

Old values in a new reality

When advertising was the main source of income for the news, we knew instinctively that Sales and Editorial had to be clearly separated to preserve the impartiality of the news. A “Chinese Wall” existed between the newsroom and its business side, and outlets went to lengths to make that separation clear.

What happens when the revenue comes straight from the readers? Does building a “wall” make sense when your journalistic mission requires understanding and serving your audience’s information needs?

With time, we’ve come to understand that analytics are not implicitly a threat to independence; that data can also be used to make a business case for old values like editorial independence and high standards – an asset that readers are willing to pay for.

It would be naive, however, not to note that the consolidation of this business model is occurring within the context of increased political polarisation and the decline of freedom of expression in several countries worldwide. Both of these realities add complexity to the development of the model and its implications for how journalism is practised. These are best described in Rasmus Kleis Nielsen’s trilemma model, which outlines how a digital news business may be forced – knowingly or unknowingly, through a process of constant trial and improvement – to choose between different combinations of our core values.

Indirect pressure: data

What information about the audience a newsroom gets – and how it is used in editorial decision-making – varies significantly. From “page views” to “time spent” to conversion data: journalists may be exposed to different metrics in real-time or in trend reports. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to analysing audience needs. The solutions working well for one outlet will not necessarily work for others.

We do know, however, that an unchecked stream of information about audiences without providing proper support to journalists (or a clear set of goals and how to achieve them) can create anxiety in newsrooms. This is a summary of what newsroom leaders had to say about data pressure:

- Ensure journalists understand the business model, and that the model respects news culture With no perfect recipe — and considering that the ingredients are constantly changing to keep pace with evolving technology and audience consumption trends – everyone I spoke to said reader revenue newsrooms require journalists who understand how the business works.

“I think it is 100% absolutely fundamental that the newsroom is aware of the business model, even if it doesn’t go beyond any more than awareness,” said Reneé Kaplan, Head of Digital Editorial Development at the FT and Assistant Editor. “A news media business becomes financially viable only if there is real collaboration across all departments. Digital business pay-for-content models are, by definition, integrated models where format, product, product experience and topics and coverage and data and marketing and sales are all inextricably linked.”

“That said, there [are] cultural limits,” she said. “Part of what makes a successful cooperation between a newsroom and its business model, more broadly, is one that knows and deeply respects and speaks newsroom and newsroom culture above all else.” - Data should direct, not dictate El País de Madrid surpassed 200,000 subscribers in April this year, only two years after it was launched. Mari Luz Peinado, a digital strategist at El País, said: “Everything is about putting the reader at the centre and finding out if we manage to deliver the news to them,” Peinado said. This perspective informs adaptation of how the news is delivered, but not what it contains.

Metrics at El País showed their culture critics – a team whose work they are proud of – didn’t do well on the digital front page. Instead of killing content, El País decided to search for different strategies to increase the readership of those pieces. Now the newspaper distributes the cultural content through a newsletter and achieves better readership levels. - Use data to deploy resources accurately Reducing the number of articles produced daily is a goal recently pursued by media outlets, such as El País, elDiario.es, FT, Denník N, and many more. Metrics can help inform that process.

- Careful data can incentivise good journalism At Denník N, a digital-born Slovakian news outlet that launched in 2014 and has surpassed 70,000 subscribers, journalists receive a bonus for articles that result in the most conversions. Contrary to the expectation that this would encourage “easy hits”, readers are consistently rewarding high-effort journalism. Four of the five top stories rewarded in the past have been long-form investigations, the fifth was a piece of analytical reportage. “But of course, in reader revenue you still have [to beware of] risks,” said founder, Tomas Bella.

Direct pressure

Spanish newspaper elDiario.es has had a membership model since it started in 2012 and its members – over 70,000 of them – account for around 50% of their income. It makes them “much more vulnerable” to those readers who try to “punish” the media outlet, said director and co-founder Escolar.

It is what Escolar described earlier as ‘Snow White Mirror Syndrome’. “We rebel against that,” he said. “We make a show of our rebellion and try to educate our community members that it is our job to contradict them many times.” This is a summary of what newsroom leaders had to say about direct audience pressure:

- Know your reasoning, be open to dialogue When readers decide to stop paying for their membership at elDiario.es , they receive an email thanking them for their support in the past and telling them they can email the editor-in-chief to complain if their decision is due to editorial reasons. Escolar receives at least three and as many as 10 emails a day with “editorial cancellations”. He answers 95% of them.

Although he convinces most readers not to drop their membership, Escolar does not respond for economic reasons: he knows that answering one by one allows him to answer a “thousand by thousand” down the line.

“You have to understand what their arguments are. What you can't do is pretend that this problem doesn't exist,” he said. “It helps us improve: both in how we explain what we are doing and, if we are doing something wrong, to correct it.” - Ideological impartiality as a long-term strategy “When our work led to the resignation of Cifuentes [a conservative], we got 10,000 new subscribers. When we showed that a [progressive] government minister had done the same fraudulent university degree, we got 25 dropouts,” recalls elDiario.es’s Escolar. “It illustrates you can have much more reward by reporting in favour of the ideological positions of your readers rather than against them.”

But not caving pays off in the long term, he said: “If we are to have credibility, it will be because we have published both stories, and not because we have silenced one.”FT’s Kaplan, reflecting on Brexit coverage, added: “the divisive issues are the ones where you most need to take into account comments within context and user data: if they are sharing a lot of content, and reading a lot, then they are taking a lot of value and our mission is accomplished.” - Prepare for backlash through excellence Journalists usually know which topics will generate a backlash from their audience. “When faced with these scenarios, exercise journalistic caution,” Escolar said. “Be very careful in applying good journalistic principles: there can be no technical faults.”

- Acknowledge the risk There will always be those who are willing to pay for coverage that plays into their ‘Snow White Mirror Syndrome’. Jakub Parusinski, the CFO of the Kyiv Independent and co-founder of The Fix, said, “There's going to be media that are just going to focus on [...] pushing various political messages, activist messages as the way to fundraise. And, you know, can you do that a little bit without going overboard? Probably. Are there big risks about going too far with it? Definitely.”

A final word on Opinion

444.hu’s Erdelyi has identified a temptation that can arise when independent outlets look at what kind of content converts readers to members easily and cheaply. In an essay on the topic, he wrote: “Opinion pieces are known to drive conversions relatively well, while the resource cost associated with their production is relatively low. From a financial perspective, newsrooms are incentivised to produce more opinion journalism and more opinionated journalism.”

In an interview for this essay, he said media outlets operating a membership model have to be “very careful” not to cave to the “seduction” of opinion – particularly in countries like Hungary, where democracy has deteriorated and independent media is struggling. “I think that is a very dangerous path, and I am aware of the danger, but I don’t have a solution as to how to deal with it. We are trying to be very conscious about our decisions and why we make them.”

Dennik N's Bella agrees with Erdelyi: “In general, I think it is easier to have reader revenue if you have strong opinions, but we don’t think it is a good thing.”

“We are cautious not to go step by step towards the extremes because the extremes would attract more people, but in a bad sense. It is a risk that is there, and we are trying to be very careful about it. You don’t have to follow your readers when they push you to an extreme. This is the risk the media must actively think about.”

For the full findings and conclusions of this paper, download Guillermo’s paper below

This project and fellowship have been made possible by the support of the Thomson Reuters Foundation.