This year’s report comes at a time when around half the world’s population have been going to the polls in national and regional elections, and as wars continue to rage in Ukraine and Gaza. In these troubled times, a supply of accurate, independent journalism remains more important than ever, and yet in many of the countries covered in our survey we find the news media increasingly challenged by rising mis- and disinformation, low trust, attacks by politicians, and an uncertain business environment.

Our country pages this year are filled with examples of layoffs, closures, and other cuts due to a combination of rising costs, falling advertising revenues, and sharp declines in traffic from social media. In some parts of the world these economic challenges have made it even harder for news media to resist pressures from powerful businesspeople or governments looking to influence coverage and control narratives.

There is no single cause for this crisis; it has been building for some time, but many of the immediate challenges are compounded by the power and changing strategies of rival big tech companies, including social media, search engines, and video platforms. Some are now explicitly deprioritising news and political content, while others have switched focus from publishers to ‘creators’, and pushing more fun and engaging formats – including video – to keep more attention within their own platforms. These private companies do not have any obligations to the news, but with many people now getting much of their information via these competing platforms, these shifts have consequences not only for the news industry, but also our societies. As if this were not enough, rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are about to set in motion a further series of changes including AI-driven search interfaces and chatbots that could further reduce traffic flows to news websites and apps, adding further uncertainty to how information environments might look in a few years.

Our report this year documents the scale and impact of these ‘platform resets’. With TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube on the rise, we look at why consumers are embracing more video consumption and investigate which mainstream and alternative accounts – including creators and influencers – are getting most attention when it comes to news. We also explore the very different levels of confidence people have in their ability to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy content on a range of popular third-party platforms around the world. For the first time in our survey, we also take a detailed look at consumer attitudes towards the use of AI in the news, supported by qualitative research in three countries (the UK, US, and Mexico). As publishers rapidly adopt AI, to make their businesses more efficient and to personalise content, our research suggests they need to proceed with caution, as the public generally wants humans in the driving seat at all times.

With publishers struggling to connect with much of the public, and growing numbers of people selectively (and in some cases continuously) avoiding the news, we have also explored different user needs to understand where the biggest gaps lie between what audiences want and what publishers currently provide. And we look at the price that some consumers are currently paying for online news and what might entice more people to join them.

An episode on the findings

This 13th edition of our Digital News Report, which is based on data from six continents and 47 markets, reminds us that these changes are not always evenly distributed. While journalism is struggling overall, in some parts of the world news media remain profitable, independent, and widely trusted. But even in these countries, we find challenges around the pace of change, the role of platforms, and how to adapt to a digital environment that seems to become more complex and fragmented every year. The overall story is captured in this Executive Summary, followed by Section 1 with chapters containing additional analysis, and then individual country and market pages in Section 2.

Here is a summary of some of the key findings from our 2024 research.

-

In many countries, especially outside Europe and the United States, we find a significant further decline in the use of Facebook for news and a growing reliance on a range of alternatives including private messaging apps and video networks. Facebook news consumption is down 4 percentage points, across all countries, in the last year.

-

News use across online platforms is fragmenting, with six networks now reaching at least 10% of our respondents, compared with just two a decade ago. YouTube is used for news by almost a third (31%) of our global sample each week, WhatsApp by around a fifth (21%), while TikTok (13%) has overtaken Twitter (10%), now rebranded X, for the first time.

-

Linked to these shifts, video is becoming a more important source of online news, especially with younger groups. Short news videos are accessed by two-thirds (66%) of our sample each week, with longer formats attracting around half (51%). The main locus of news video consumption is online platforms (72%) rather than publisher websites (22%), increasing the challenges around monetisation and connection.

-

Although the platform mix is shifting, the majority continue to identify platforms including social media, search, or aggregators as their main gateway to online news. Across markets, only around a fifth of respondents (22%) identify news websites or apps as their main source of online news – that’s down 10 percentage points on 2018. Publishers in a few Northern European markets have managed to buck this trend, but younger groups everywhere are showing a weaker connection with news brands than they did in the past.

-

Turning to the sources that people pay most attention to when it comes to news on various platforms, we find an increasing focus on partisan commentators, influencers, and young news creators, especially on YouTube and TikTok. But in social networks such as Facebook and X, traditional news brands and journalists still tend to play a prominent role.

-

Concern about what is real and what is fake on the internet when it comes to online news has risen by 3 percentage points in the last year with around six in ten (59%) saying they are concerned. The figure is considerably higher in South Africa (81%) and the United States (72%), both countries that have been holding elections this year.

-

Worries about how to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy content in online platforms is highest for TikTok and X when compared with other online networks. Both platforms have hosted misinformation or conspiracies around stories such as the war in Gaza, and the Princess of Wales’s health, as well as so-called ‘deep fake’ pictures and videos.

-

As publishers embrace the use of AI we find widespread suspicion about how it might be used, especially for ‘hard’ news stories such as politics or war. There is more comfort with the use of AI in behind-the-scenes tasks such as transcription and translation; in supporting rather than replacing journalists.

-

Trust in the news (40%) has remained stable over the last year, but is still four points lower overall than it was at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic. Finland remains the country with the highest levels of overall trust (69%), while Greece (23%) and Hungary (23%) have the lowest levels, amid concerns about undue political and business influence over the media.

-

Elections have increased interest in the news in a few countries, including the United States (+3), but the overall trend remains downward. Interest in news in Argentina, for example, has fallen from 77% in 2017 to 45% today. In the United Kingdom interest in news has almost halved since 2015. In both countries the change is mirrored by a similar decline in interest in politics.

-

At the same time, we find a rise in selective news avoidance. Around four in ten (39%) now say they sometimes or often avoid the news – up 3 percentage points on last year’s average – with more significant increases in Brazil, Spain, Germany, and Finland. Open comments suggest that the intractable conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East may have had some impact. In a separate question, we find that the proportion that say they feel ‘overloaded’ by the amount of news these days has grown substantially (+11pp) since 2019 when we last asked this question.

-

In exploring user needs around news, our data suggest that publishers may be focusing too much on updating people on top news stories and not spending enough time providing different perspectives on issues or reporting stories that can provide a basis for occasional optimism. In terms of topics, we find that audiences feel mostly well served by political and sports news but there are gaps around local news in some countries, as well as health and education news.

-

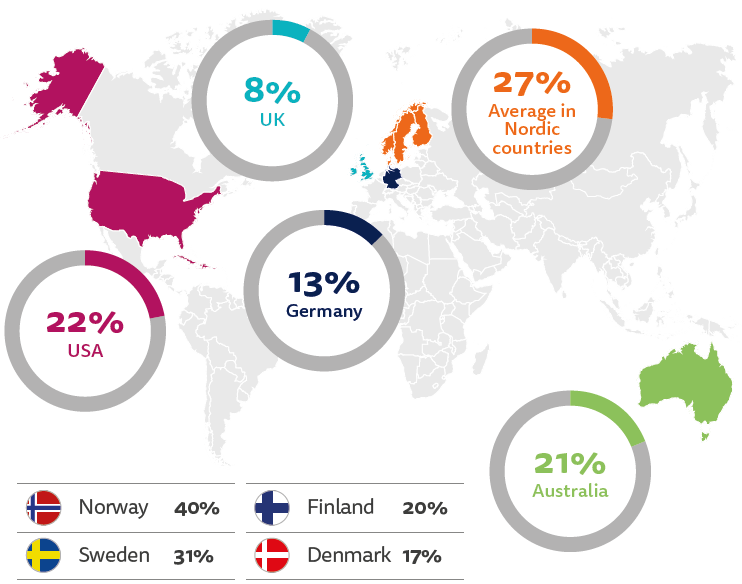

Our data show little growth in news subscription, with just 17% saying they paid for any online news in the last year, across a basket of 20 richer countries. North European countries such as Norway (40%) and Sweden (31%) have the highest proportion of those paying, with Japan (9%) and the United Kingdom (8%) amongst the lowest. As in previous years, we find that a large proportion of digital subscriptions go to just a few upmarket national brands – reinforcing the winner-takes-most dynamics that are often linked with digital media.

-

In some countries we find evidence of heavy discounting, with around four in ten (41%) saying they currently pay less than the full price. Prospects of attracting new subscribers remain limited by a continued reluctance to pay for news, linked to low interest and an abundance of free sources. Well over half (55%) of those that are not currently subscribing say that they would pay nothing for online news, with most of the rest prepared to offer the equivalent of just a few dollars per month, when pressed. Across markets, just 2% of non-payers say that they would pay the equivalent of an average full price subscription.

-

News podcasting remains a bright spot for publishers, attracting younger, well-educated audiences but is a minority activity overall. Across a basket of 20 countries, just over a third (35%) access a podcast monthly, with 13% accessing a show relating to news and current affairs. Many of the most popular podcasts are now filmed and distributed via video platforms such as YouTube and TikTok.

The great platform reset is underway

Online platforms have shaped many aspects of our lives over the last few decades, from how we find and distribute information, how we are advertised to, how we spend our money, how we share experiences, and most recently, how we consume entertainment. But even as online platforms have brought great convenience for consumers – and advertisers have flocked to them – they have also disrupted traditional publishing business models in very profound ways. Our data suggest we are now at the beginning of a technology shift which is bringing a new wave of innovation to the platform environment, presenting challenges for incumbent technology companies, the news industry, and for society.

Platforms have been adjusting strategies in the light of generative AI, and are also navigating changing consumer behaviour, as well as increased regulatory concerns about misinformation and other issues. Meta in particular has been trying to reduce the role of news across Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, and has restricted the algorithmic promotion of political content. The company has also been reducing support for the news industry, not renewing deals worth millions of dollars, and removing its news tab in a number of countries.1

The impact of these changes, some which have been going on for a while, is illustrated by our first chart which uses aggregated data from 12, mostly developed, markets we have been following since 2014. It shows declining, though still substantial, reach for Facebook over time – down 16pp since 2016 – as well as increased fragmentation of attention across multiple networks. A decade ago, only Facebook and YouTube had a reach of more than 10% for news in these countries, now there are many more networks, often being used in combination (several of them are owned by Meta). Taken together, platforms remain as important as ever – but the role and strategy of individual platforms is changing as they compete and evolve, with Facebook becoming less important, and many others becoming relatively more so.

The previous chart also highlights the strong shift towards video-based networks such as YouTube, TikTok (and Instagram), all of which have grown in importance for news since the COVID-19 pandemic drove new habits. Faced with new competition, both Facebook and X have been refocusing their strategies, looking to keep users within the platform rather than link out to publishers as they might have done in the past. This has involved a prioritisation of video and other proprietary formats. Industry data show that the combined effect of these changes was to reduce traffic referrals from Facebook to publishers by 48% last year and from X by 27%.2 Looking at survey data across our 47 markets we find much regional and country-based variation in the use of different networks, with the fastest changes in the Global South, perhaps because they tend to be more dependent on social media for news.

TikTok remains most popular with younger groups and, although its use for any purpose is similar to last year, the proportion using it for news has grown to 13% (+2) across all markets and 23% for 18–24s. These averages hide rapid growth in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. More than a third now use the network for news every week in Thailand (39%) and Kenya (36%), with a quarter or more accessing it in Indonesia (29%) and Peru (27%). This compares with just 4% in the UK, 3% in Denmark, and 9% in the United States. The future of TikTok remains uncertain in the US following concerns about Chinese influence and it is already banned in India, though similar apps, such as Moj, Chingari, and Josh, are emerging there.

The growing reach of TikTok and other youth-orientated networks has not escaped the attention of politicians who have incorporated it into their media campaigns. Argentina’s new populist president, Javier Milei, runs a successful TikTok account with 2.2m followers while the new Indonesian president, Prabowo Subianto, swept to victory in February using a social media campaign featuring AI-generated images, rebranding the former hard-line general as a cute and charming dancing grandpa. We explore the implications for trust and reliability of information later in this report.

Shift to video networks brings different dynamics

Traditional social networks such as Facebook and Twitter were originally built around the social graph – effectively this means content posted directly by friends and contacts (connected content). But video networks such as YouTube and TikTok are focused more on content that can be posted by anybody – recommended content that does not necessarily come from accounts users have chosen to follow.

In previous research (Digital News Report 2021, 2023) we have shown that when it comes to online news, most audiences still prefer text because of its flexibility and control, but that doesn’t mean that video – and especially short-form video – is not becoming a much bigger part of media diets. Across countries, two-thirds (66%) say they access a short news video, which we defined as a few minutes or less, at least once a week, again with higher levels outside the US and Western Europe. Almost nine in ten of the online population in Thailand (87%), access short-form videos weekly, with half (50%) saying they do this every day. Americans access a little less often (60% weekly and 20% daily), while the British consume the least short-form news (39% weekly and just 9% daily).

Live news streams and long-form recordings are also widely consumed. Taking the United States as an example, we can see how under 35s consume the most of each format, with older people being relatively less likely to consume live or long-form video.

One of the reasons why news video consumption is higher in the United States than in most European countries is the abundant supply of political content from both traditional and non-traditional sources. Some are creators native to online media. Others have come from broadcast backgrounds. In the last few years, a number of high-profile TV anchors, including Megyn Kelly, Tucker Carlson, and Don Lemon, have switched their focus to online platforms as they look to take advantage of changing consumer behaviour.

Carlson’s interview with Russian president Vladimir Putin received more than 200m plays on X and 34m on his YouTube channel. In the UK, another controversial figure, Piers Morgan, recently left his daily broadcast show on Talk TV in favour of the flexibility and control offered as an independent operator working across multiple streaming platforms. (It is worth noting that many of these platform moves came only after the person in question walked out on or were ditched by their former employers on mainstream TV.)

The jury is currently out on whether these big personalities can build robust traffic or sustainable businesses within platform environments. There is a similar challenge for mainstream publishers who find platform-based videos harder to monetise than those consumed via owned and operated websites and apps.

YouTube and Facebook remain the most important platforms for online news video overall (see next chart), but we see significant market differences, with Facebook the most popular for video news in the Philippines, YouTube in South Korea, and X and TikTok playing a key role in Nigeria and Indonesia respectively. YouTube is also the top destination for under 25s, though TikTok and Instagram are not far behind.

Older viewers still like to consume much of their video through news websites, though the majority say they mostly access video via third-party platforms. Only in countries such as Norway do we find that getting on for half of users (45%) say their main video consumption is via websites, a reflection of the strength of brands in that market, a commitment to a good user experience, and a strategy that restricts the number of publisher videos that are posted to platforms like Facebook and YouTube.

Where do people pay attention when using online platforms?

One of the big challenges of the shift to video networks with a younger age profile is that journalists and news organisations are often eclipsed by news creators and other influencers, even when it comes to news.

This year we repeated a question we asked first in 2021 about where audiences pay most attention when it comes to news on various platforms. As in previous years, we find that across markets, while mainstream media and journalists often lead conversations in X and Facebook, they struggle to get as much attention in Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok where alternative sources and personalities, including online influencers and celebrities, are often more prominent.

It is a similar story across many markets, though differences emerge when we look at specific online networks and at a country level. In the following chart we compare attention around news content on YouTube, the second largest network overall. We find that alternative sources and online influencers play a bigger role in both the United States and Brazil than is the case in the United Kingdom.

But who are these personalities and celebrities and what kind of alternative sources are attracting attention? To answer these questions, we asked respondents that had selected each option to list up to three mainstream accounts they followed most closely and then three alternative ones (e.g. alternative accounts, influencers, etc). We then counted and coded these responses.

In the United States, in particular, we find a wide range of politically partisan voices including Tucker Carlson, Alex Jones (recently reinstated on X), Ben Shapiro, Glenn Beck, and many more. These voices come mostly from the right, with a narrative around a ‘trusted’ alternative to what they see as the biassed liberal mainstream media, but there is also significant representation on the progressive left (David Pakman and commentators from Meidas Touch). The top 10 named individuals in the US list are all men who tend to express strong opinions about politics.

Partisan voices (from both left and right) are an important part of the picture elsewhere, but we also find diverse perspectives and new approaches to storytelling. In France, Hugo Travers, 27, known online as Hugo Décrypte, has become a leading news source for young French people for his explanatory videos about politics (2.6m subscribers on YouTube and 5.8m on TikTok). Our data show that across all networks he gets more mentions than traditional news brands such as Le Monde or BFMTV. According to our data, the average audience age of his followers is just 27, compared to between 40 and 45 for large traditional brands such as Le Monde or BFM TV.

Youth-focused brands Brut and Konbini were also widely cited in France, while in the UK, Politics Joe and TLDR News, set up by Jack Kelly, attract attention for videos that try to make serious topics accessible for young people. The most mentioned TikTok news creator in the UK is Dylan Page, who has more than 10m followers on the platform. In the United States, Vitus Spehar presents a fun daily news round-up, often from a prone position on the floor, @underthedesknews (a satirical dig at the classic TV format).

Youth-based news influencers around the world

Coverage of war and conflict

We also found a number of accounts sharing videos about the wars in Gaza and Ukraine. With mainstream news access restricted, young social media influencers in Gaza, Yemen, and elsewhere have been filling in the gaps – documenting the often-brutal realities of life on the ground. Because these videos are posted by many different accounts and ordinary people, it is hard to quantify the impact, but our methodology does pick up a few individual influencer accounts as well as campaigning groups that pull together footage from across social media. As one example, the Instagram account Eye on Palestine appears in our data across a number of countries. The account says it brings ‘the sounds and images that official media does not show’. WarMonitor, one of a number of influential accounts that have been recommended by prominent figures such as Elon Musk, has added hundreds of thousands of followers during the Israel–Palestine conflict.

Finally, celebrities such as Taylor Swift, the Kardashians, and Lionel Messi were widely mentioned by younger people, mostly in reference to Instagram, despite the fact that they rarely talk about politics. This suggests that younger people take a wide view of news, potentially including updates on a singer’s tour dates, on fashion, or on football.

Motivations for using social video

In analysing open comments, we found three core reasons why audiences are attracted to video and other content in social and video platforms.

First, respondents, including many younger ones, say the comparatively unfiltered nature of much of the coverage makes it come across as more trustworthy and authentic than traditional media. ‘I like the videos that were taken by an innocent bystander. These videos are unedited and there is no bias or political spin,’ says one.3 There is an enduring belief that videos are harder to falsify, while enabling people to make up their own mind, even as the development of AI may lead more people to question it.

Secondly, people talk about the convenience of having news served to you on a platform where you already spend time, which knows your interests, and where ‘the algorithm feeds suggestions based on previous viewing’.

Thirdly, social video platforms are valued for the different perspectives they bring. For some people that meant a partisan perspective that aligns with their interests, but for others it related to the greater depth around a personal passion or a wider range of topics to explore.

It is important to note that very few people only use online video for news each week – around 4% across countries according to our data. The majority use a mix of text, video, and audio – and a combination of mainstream brands that may or may not be supplemented by alternative voices. But as audiences consume more content in these networks, they sometimes worry less about where the content comes from, and more about the convenience and choice delivered within their feed. Though there are examples of successful video consumption within news websites and apps, for most publishers the shift towards video presents a difficult balancing act. How can they take advantage of a format that can engage audiences in powerful ways, including younger ones, while developing meaningful relationships – and businesses – on someone else’s platform?

To what extent do people feel confident about identifying trustworthy news in different online platforms?

In this critical year of elections, many worry about the reliability of content, about the scope for manipulation of online platforms by ‘bad actors’, over how some domestic politicians and media personalities express themselves, and about the opaque ways in which platforms themselves select and promote content.

Across markets the proportion of our respondents that say they are worried about what is real and what is fake on the internet overall is up 3pp from 56% to 59%. It is highest in some of the countries holding polls this year, including South Africa (81%), the United States (72%), and the UK (70%). Taking a regional view, we find the highest levels of concern in Africa (75%) and lower levels in much of Northern and Western Europe (e.g., Norway 45% and Germany 42%).

Previous research shows that these audience concerns about misinformation are often driven less by news that is completely ‘made up’ and more about seeing opinions and agendas that they may disagree with – as well as journalism they regard as superficial and unsubstantiated. In this context it is perhaps not surprising that politics remains the topic that engenders the most concern about ‘fake or misleading’ content, along with health information and news about the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

Against this backdrop of widespread concern, we have, for the first time, asked users of specific online platforms, how easy or difficult they find it to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy content. Given its increasing use for news – and its much younger age profile – it is worrying to find that more than a quarter of TikTok users (27%) say they struggle to detect trustworthy news, the highest score out of all the networks covered. A further quarter have no strong opinion and around four in ten (44%) say they find it easy. Fact-checkers and others have been paying much more attention to the network recently, with Newsguard reporting in 2022 that a fifth (20%) of a sample of searches on prominent news topics such as Ukraine and COVID vaccines contained misinformation.4 Most recently it was at the centre of a flood of unfounded rumours and conspiracies about the Princess of Wales after her hospital operation. A significant proportion of X users (24%) also say that it is hard to pick out trustworthy news. This may be because news plays an outsized role on the platform, or because of the wide range of views expressed, further encouraged by Elon Musk, a self-declared free speech advocate, since he took over the company.

The numbers are only a bit lower in some of the largest networks such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and WhatsApp, which have all been implicated in various misinformation problems too.

While there is widespread concern about different networks, it is also important to recognise that many people are confident about their ability to tell trustworthy and untrustworthy news and information apart. In fact, around half of respondents using each network say they find it easy to do so, including many younger and less educated users – even if these perceptions may or may not be based on reality. All of the major social and video platforms recognise these challenges, and have been boosting their technical and human defences, not least because of the potential for a flood of AI-generated synthetic content in this year’s elections.

In exploring country differences, we find that people in Western European countries such as Germany (see the next chart) are less confident about their ability to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy information on X and TikTok than respondents in the United States. This may reflect very different official and media narratives about the balance between free speech and online harms. The EU has introduced legislation such as the Digital Services Act, imposing greater obligations on platforms in the run-up to June’s EU Parliament elections.5 X is currently being investigated over suspected breaches of content moderation rules.

But even within the United States, which has lower concern generally, we find sharp differences based on political beliefs. Amid bitter debates over de-platforming, some voices on the left have been calling for more restrictions and many on the right insisting on even more free speech. We see this political split clearly in the data, especially in terms of attitudes to X and to some extent YouTube.

In our data, people on the left are much more suspicious of content they see in both networks, but other platforms are seen as mostly neutral in this regard. In no other market do we see the same level of polarisation around X, but the same broad left-right dynamics are at play, with the left more uncomfortable about the societal impact of harmful online content.

In some African markets, such as Kenya, we see a significant difference in concern over TikTok compared with other popular networks such as X or WhatsApp, the most used network for news. The app has been labelled ‘a serious threat to the cultural and religious values of Kenya’ in a petition to parliament after being implicated in the sharing of adult content, misinformation, and hate speech.6 But one other reason for TikTok’s higher score may be because most content there is posted by people they don’t know personally. WhatsApp posts tend to come from a close social circle, who are likely to be more trusted. Paradoxically, this could mean that information spread in WhatsApp carries more danger, because defences may be lower.

Fears around AI and misinformation

The last year has seen an increased incidence of so-called ‘deepfakes’, generated by AI including an audio recording falsely purporting to be Joe Biden asking supporters not to vote in a primary, a campaign video containing manipulated photos of Donald Trump, and artificially generated pictures of the war in the Middle East, posted by supporters of both the Palestinian and Israeli sides aimed at winning sympathy for their cause.

AI-generated (fake) pictures from the war have been widely circulated on social media

Our qualitative research suggests that, while most people do not think they have personally seen these kinds of synthetic images or videos, some younger, heavy users of social media now think they are coming across them regularly.

In the US some of our participants felt widespread use of generative AI technologies was likely to make detecting misinformation more difficult, especially around important subjects such as politics and elections; others worried about the lack of transparency and the potential for discrimination against minority groups.

Others took a more balanced view, noting that these technologies could be used to provide more relevant and useful content, while also recognising the risks.

Journalistic uses of artificial intelligence

News organisations have reported extensively on the development and impact of AI on society, but they are also starting to adopt these technologies themselves for two key reasons. First, they hope that automating behind-the-scenes processes such as transcription, copy-editing, and layout will substantially reduce costs. Secondly, AI technologies could help to personalise the content itself – making it more appealing for audiences. They need to do this without reducing audience trust, which many believe will become an increasingly critical asset in a world of abundant synthetic media.

In the last year, we have seen media companies deploying a range of AI solutions, with varying degrees of human oversight. Nordic publishers, including Schibsted, now include AI-generated ‘bullet points’ at the top of many of their titles’ stories to increase engagement. One German publisher uses an AI robot named Klara Indernach to write more than 5% of its published stories,7 while others have deployed tools such as Midjourney or OpenAI’s Dall-E for automating graphic illustrations. Meanwhile, Digital News Report country pages from Indonesia, South Korea, Slovakia, Taiwan, and Mexico, amongst others, reference a range of experimental chatbots and avatars now presenting the news. Nat is one of three AI-generated news readers from Mexico’s Radio Fórmula, used to deliver breaking news and analysis through its website and across social media channels.8

Nat, one of Radio Fórmula’s AI-generated news readers

Elsewhere we find content farms increasingly using AI to rewrite news, often without permission and with no human checks in the loop. Industry concerns about copyright and about potential mistakes (some of which could be caused by so-called hallucinations) are well documented, but we know less about how audiences feel about these issues and the implications for trust overall.

Across 28 countries where we included questions, we find our survey respondents to be mostly uncomfortable with the use of AI in situations where content is created mostly by the AI with some human oversight. By contrast, there is less discomfort when AI is used to assist (human) journalists, for example in transcribing interviews or summarising materials for research. Here respondents are broadly more comfortable than uncomfortable.

Our findings, which also show that respondents in the US are significantly more comfortable about different uses of AI than those living in Europe, may be linked to the cues people are getting from the media. British press coverage of AI, for example, has been characterised as overly negative and sensationalist,9 and UK scores for comfort with less closely monitored use of AI are the lowest in our survey (10%). By contrast, the leading role of US companies and the opportunities for jobs and growth play a bigger part in US media narratives. Across countries, comfort levels are higher with younger groups who are some of the heaviest users of AI tools such as ChatGPT.

Our research also indicates that people who tend to trust the news in general are also more likely to be comfortable with uses of AI where humans (journalists) remain in control, compared with those that don’t. We find comfort gaps ranging from 24 percentage points in the US to 10 percentage points in Mexico. Our qualitative research on AI suggests that trust will be a key issue going forward, with many participants feeling that traditional media have much to lose.

Comfort with AI is also closely related to the importance and seriousness of the subject being discussed. People say they feel less comfortable with AI-generated news on topics such as politics and crime, and more comfortable with sports, arts, or entertainment news, subjects where mistakes tend to have less serious consequences and where there is potentially more value in personalisation of the content.

While participants were generally more concerned for some topics rather than others, there were some important nuances. For example, some could see the value in using AI to automate local election stories to provide a quicker comprehensive service, as these tended to be fact-based and didn’t involve the AI making political judgements.

Finally, we find that comfort levels about the different uses of AI tend to be higher with people who have read or heard more about it, even if many remain cautious. This suggests that, as people use the technology and find it personally useful, they may take a more balanced view of the risks and the benefits going forward.

Overall, we are still at the early stages of journalists’ usage of AI, but this also makes it a time of maximum risk for news organisations. Our data suggest that audiences are still deeply ambivalent about the use of the technology, which means that publishers need to be extremely cautious about where and how they deploy it. Wider concerns about a flood of synthetic content in online platforms means that trusted brands that use the technologies responsibly could be rewarded, but get things wrong and that trust could be easily lost.

Gateways to news and the importance of search and aggregator portals

Publishers are not just concerned about falling referrals from social media but also about what might happen with search and other aggregators if chatbot interfaces take off. Google and Microsoft are both experimenting with integrating more direct answers to news queries generated by AI and a range of existing and new mobile apps are also looking to create new experiences that provide answers without requiring a click-through to a publisher.

It is important to note that across all markets, search and aggregators, taken together (33%), are a more important gateway to news than social media (29%) and direct access (22%). A large proportion of mobile alerts (9%) are also generated by aggregators and portals, adding to the concerns about what might happen next.

Unlike social media, search is seen as important across all age groups – 25% of under 35s also prefer to start news journeys with search – and because people are often actively looking for information, the resulting news journey tends to be more valuable for publishers than social fly-by traffic.

Looking at preferred gateways over time we find that search has been remarkably consistent while direct traffic has become less important and social has grown consistently (until this year). Beneath the averages however we do see significant differences across countries. Portals, which often incorporate search engines and mobile apps, are particularly important in parts of Asia. In Japan, Yahoo! News and Line News remain dominant, while local tech giants Naver and Daum are the key access points in South Korea – developing their own AI solutions. In the Czech Republic, Seznam has been an important local search engine, now supplemented with its own news service and also an innovator in AI. Social and video networks tend to be more important in other parts of Asia, as well as Africa and Latin America, but direct traffic still rules in a few parts of Northern Europe where intermediaries have historically played a smaller role. Publishers without regular direct access will be more vulnerable to platform changes and will inevitably find it harder to build subscription businesses.

Even in countries with relatively strong brands such as the UK, we find significant generational differences when it comes to gateways. Older people are more likely to maintain direct connections, but in the last few years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen both 18–24s and now 25–35s becoming less likely to go directly to a website or app. Across markets we see the same trends with the gap between generations just as significant as country-based differences, if not more.

It is also worth noting the increasing success of mobile aggregators in some countries, many of which are increasingly powered by AI. In the United States, News Break (9%), which was founded by a Chinese tech veteran, has been growing fast with a similar market share to market leader Apple News (11%). In Asian markets, multiple aggregator apps and portals play important gateway and consumption roles, with AI features typically driving ever greater levels of personalisation.

Mobile aggregators tend to be more popular with younger news consumers and are becoming a bigger part of the picture overall, partly fuelled by notifications on relevant topics. In terms of search, there is little evidence that search traffic is drying up and it is certainly not a given that consumers will rush to adopt chatbot interfaces. Even so, publishers expect traffic from search and other gateways to be more unpredictable in the future and will be exploring alternatives with some urgency.

The business of news: subscriptions stalling?

A difficult advertising market, combined with rising costs and the decline in traffic from social media, has put more pressure on the bottom line, especially for publishers that have relied on platform distribution. These factors, together with news about US-based layoffs at the Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, NBC, Business Insider, Wall Street Journal, Condé Nast, and Sports Illustrated, recently led the New Yorker to publish an article titled: ‘Is the Media Prepared for an Extinction-Level Event?’. The article argued that certain kinds of public interest journalism were now uneconomic and a new, more audience-focused approach was needed.

In this context, and with similar pressures all over the world, we are seeing news media looking to introduce or strengthen reader payment models such as subscription, membership, and donation. Paid models have been a rare bright spot in some of the richer countries in our survey, where publishers still have strong direct connections with readers, but have been difficult to make work elsewhere. As in previous years, our survey shows a significant proportion paying for online news in Norway (40%) and Sweden (31%) and over a fifth in the United States (22%) and Australia (21%), but much lower numbers in Germany (13%), France (11%), Japan (9%), and the UK (8%). There has been very little movement in these top line numbers in the last year.

Proportion that paid for any online news in the last year

Selected countries

Via subscription/membership/donation or one-off payment

Across 20 countries, where a significant number of publishers are pushing digital subscriptions, payment levels have almost doubled since 2014 from 10% to 17%, but following a significant bump during the COVID pandemic, growth has slowed. Publishers have already signed up many of those prepared to pay, and converted some of the more intermittent payers to ongoing subscriptions or donations. But amid a cost-of-living crisis, it is proving difficult to persuade most of the public to do the same.

In most countries, we continue to see a ‘winner takes most’ market, with a few upmarket national titles scooping up a big proportion of users. In the United States, for example, the New York Times recently announced that it has over 10m subscribers (including 9.9m digital only) while the Washington Post’s numbers have reportedly declined. Having said that, we do find a growing minority of countries where people are paying, on average, for more than one publication, including in the United States, Switzerland, Poland, and France (see table below).

This may be because some publishers in these markets are bundling together titles in an all-access subscription (e.g., New York Times, Schibsted, Amedia, Bonnier, Mediahuis). As one example, Amedia’s +Alt product, which offers 100 newspapers, magazines, and podcasts, now accounts for 10% of Norwegian subscriptions, up 6 percentage points this year.

In Nordic countries, it is worth noting the high proportion of local titles being paid for online. In Canada, Ireland, and Switzerland, a significant proportion of subscriptions are going to foreign publishers.

Heavy discounting persists in most but not all markets

This year we have looked at the price being paid for main news subscriptions in around 20 countries and compared this with the price that the main publications are charging for news. The results show that in the US and UK a large number of people are paying a very small amount (often just a few pounds or dollars), with many likely to be on low-price trials, as we found in last year’s qualitative research.10 In the next chart we find that well over half of those in the US who are paying for digital news report paying less than the median cost of a main subscription ($16), often much less. By contrast, in Norway, we see a different pattern with fewer people paying a very small amount and a larger number grouped around the median price, which in any case is much higher than in the US (the equivalent of $25).

The reasons for these differences become clearer when we compare the proportion that are paying the full sticker price for each brand. This allows us to estimate the proportion of subscribers in each country that are paying full price and the proportion that may be on a trial or other special deal. Using this methodology, we find significant differences between countries, with more than three-quarters (78%) in Poland paying less than full price, four in ten (46%) in the United States, but fewer in Norway (38%), Denmark (25%), and France (21%). It is not only the case that more people pay for digital news in the Nordic countries. It is also the case that fewer of them are paying a heavily discounted rate, and in Norway the median price is much higher than in other rich countries such as France, the UK, and the US.

We also asked those not currently paying, what might be a fair price, if anything? Across markets just 2% of non-payers say they would pay the equivalent of an average full price subscription, with 55% saying they wouldn’t be prepared to pay anything. That last number is a bit lower in Norway (45%) but considerably higher in the UK (69%) and Germany (68%). In a few markets in the Global South, such as Brazil, we do find more willingness to pay something, but it rarely amounts to more than the equivalent of a few US dollars.

Not every publisher can expect to make reader revenue work, in large part because much of the public basically does not believe news is worth paying for, and continues to have access to plenty of free options from both commercial, non-profit, and in some countries, public service providers. But for others, building digital subscriptions based on distinctive content is the main hope for a sustainable future. Discounting is an important part of persuading new customers to sample the product but publishers will hope that over time, once the habit is created, they can increase prices. It is likely to be a long and difficult road with few winners and many casualties along the way.

Trust levels stable – have we reached the bottom?

There is little evidence that upcoming elections or the increased prevalence of generative AI has so far had any material impact on trust in the news. Across markets, around four in ten (40%) say they trust most news most of the time, the same score as last year. Finland remains the country with the highest levels of trust (69%), Greece and Hungary (23%) have the lowest levels. Morocco, which was included in the survey for the first time, has a relatively low trust rating (31%), compared with countries elsewhere in Africa, a reflection perhaps of the fact that media control is largely in the hands of political and business elites.

Low trust scores in some other countries such as the US (32%), Argentina (30%), and France (31%) can be partly linked to high levels of polarisation and divisive debates over politics and culture.

As always, it is important to underline that our data are based on people’s perceptions of how trustworthy the media, or individual news brands, are. These scores are aggregates of subjective opinions, not an objective measure of underlying trustworthiness, and as our previous work has shown, any year-on-year changes are often at least as much about political and social factors as narrowly about the news itself.11

This year, we have also been exploring the key factors driving trust or lack of trust in the news media. We find that high standards, a transparent approach, lack of bias, and fairness in terms of media representation are the four primary factors that influence trust. The top responses are strongly linked and are consistent across countries, ages, and political viewpoints. An overly negative or critical approach, which is much discussed by politicians when critiquing the media, is seen as the least important reason in our list, suggesting that audiences still expect journalists to ask the difficult questions.

These results may give a clear steer to media companies on how to build greater trust. Most of the public want news to be accurate, fair, avoid sensationalism, be open about any agendas and biases including lack of diversity, own up to mistakes – and not pull punches when investigating the rich and powerful. People do not necessarily agree on what this looks like in practice, or which individual brands deliver on it. But what they hope news will offer is remarkably similar across many different groups.

Audience interest in transparency and openness seems to chime with some of the ideas behind recent industry initiatives, such as the Trust Project, a non-profit initiative that encourages publishers to reveal more of their workings using so-called ‘trust indicators’, the Journalism Trust Initiative orchestrated by Reporters without Borders, and others. Some large news organisations, such as the BBC, have gone further, creating units or sub-brands that answer audience questions or aim to explain how the news is checked. BBC Verify, launched in May 2023 aims to show and share work behind the scenes to check and verify information, especially images and video content in an era where misinformation has been growing. ‘People want to know not just what we know (and don't know), but how we know it,’ says BBC News CEO Deborah Turness. Leaving aside the risk that journalists and members of the public often mean different things when talking about transparency, with the former focusing on reporting practices, the latter often on their suspicion that ulterior commercial and/or political motives are at play, our data suggest that these initiatives may not work for all audiences. Transparency is considered most important amongst those who already trust the news (84%), but much less for those are generally distrustful (68%) where there is a risk that it hardens the position of those already suspicious of a brand, if they feel that verification will not be equally applied to both sides of an argument.12 Those that are less interested in the news are also less likely to feel that being transparent about how the news is made is important.

Attention loss, news avoidance, and news fatigue

For several years we have pointed to a number of measures that suggest growing ambivalence about the news, despite – or perhaps because of – the uncertain and chaotic times in which we live. Interest in news continues to fall in some markets, but has stabilised or increased in others, especially those like Argentina and the United States that are going through, or have recently held, elections.

The long-term trend, however, is down in every country apart from Finland, with high interest halving in some countries over the last decade (UK 70% in 2015; 38% in 2024). Women and young people make up a significant proportion of that decline.

While news interest may have stabilised a bit this year, the proportion that say they selectively avoid the news (sometimes or often) is up by 3pp this year to 39% – a full 10pp higher than it was in 2017. Notable country-based rises this year include Ireland (+10pp), Spain (+8pp), Italy (+7pp), Germany (+5pp), Finland (+5pp), the United States (+5pp), and Denmark (+4pp). The underlying reasons for this have not changed. Selective news avoiders say the news media are often repetitive and boring. Some tell us that the negative nature of the news itself makes them feel anxious and powerless.

Selected news avoidance at highest levels recorded

All markets

But it is not just that the news can be depressing, it is also relentless. Across markets, the same proportion, around four in ten (39%) say they feel ‘worn out’ by the amount of news these days, up from 28% in 2019, frequently mentioning the way that coverage of wars, disasters, and politics was squeezing out other things. The increase has been greater in Spain (+18), Denmark (+16pp), Brazil (+16pp), Germany (+15pp), South Africa (+12pp), France (+9pp), and the United Kingdom (+8pp), but a little less in the United States (+3pp) where news fatigue was a bigger factor five years ago. There are no significant differences by age or education, though women (43%) are much more likely to complain about news overload than men (34%).

Since we started tracking these issues, usage of smartphones has increased, as has the number of notifications sent from apps of all kinds, perhaps contributing to the sense that the news has become hard to escape. Platforms that require volume of content to feed their algorithms are potentially another factor driving these increases. It was notable that in our industry survey, at the start of 2024, most publishers said they were planning to produce more videos, more podcasts, and more newsletters this year.13

User needs and information gaps

Industry leaders recognise the twin challenges of news fatigue and news avoidance, especially around long-running stories such as the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. At the same time, disillusion with politics in general may be contributing to declining interest, especially with younger news consumers, as previous reports have shown. Editors are looking for new ways to cover these important stories, by making the news more accessible and engaging – as well as broadening the news agenda but without ‘dumbing down’.

One way in which publishers have been trying to square this circle has been through a ‘user needs’ model, where stories that update people about the latest news are supplemented by commissioning more that educate, inspire, provide perspective, connect, or entertain.

Originally based on audience research at the BBC, the model has been implemented by a number of news organisations around the world. In our survey this year, we asked about eight different needs included in User Needs 2.0, which are nested in four basic needs of knowledge, understanding, feeling, and doing.14 Our findings show that the three most important user needs globally are staying up to date (‘update me’), learning more (‘educate me’), and gaining varied perspectives (‘give me perspective’). This is pretty consistent across different demographic groups, although the young are a bit more interested in stories that inspire, connect, and entertain when compared with older groups. In the United States, for example, over half (52%) of under 35s think having stories that make them feel better about the world is very or extremely important, compared with around four in ten (43%) of over 35s.

We also asked about how good the media were perceived to be at satisfying each user need. By combining these data with the data on importance, we can create what we call a User Needs Priority Index. This is a form of gap analysis, whereby we take the percentage point gap between the proportion that think a particular need is important and the proportion that think the news media do a good job of providing it and multiply this by the overall importance (as a decimal) to identify the most important gaps. Audiences say, for example, that updating is the most important need, but also think that the media do a good job in this area already. By contrast, there is a much bigger gap in providing different perspectives (e.g. more context, wider set of views) and also around news that ‘makes me feel better about the world’ (offers more hope and optimism).

News organisations may draw different conclusions from these data, depending on their own mission and target audience, but taken as a whole, it is clear news consumers would prefer to dial down the constant updating of news, while dialling up context and wider perspectives that help people better understand the world around them. Most people don’t want the news to be made more entertaining, but they do want more stories that provide more personal utility, help them connect with others, and give people a sense of hope.

Agenda and topic gaps

Adopting a user needs model is one way to address some of the issues that lie behind selective news avoidance and low engagement, but a topic-based lens may also be useful. When looking at levels of interest in different subject areas by age, we find commonalities but also some stark differences. For all age groups, local and international news are considered the most important topics, but there is less consensus around political news. This doesn’t feature in the top five for under-35s but it is a very different story for over-45s where politics remains firmly in the top three. Younger groups are more interested in the environment and climate change, as well as other subjects such as wellness, which are less of a priority for older groups.

If anything, we find even bigger gaps around gender, with men more interested in politics and sport; women more interested in health/wellness and the environment. Much of this is not new but a reminder that older, male-dominated newsrooms may not always be instinctively in tune with the needs of those who don’t look or think like them.

Beyond interest, we also asked respondents to what extent, if at all, they felt their information needs are being met around each of these topics. Across countries we find that most people feel their needs around sport and politics (and often celebrity news) are well served, while there are substantial gaps in some other areas such education, environment, mental health, and social justice.

Local news is a mixed bag. In some countries, including the United States, more than two-thirds (68%) feel that most or all of their needs are being met, despite the loss of many local newspaper titles and journalist jobs over the past decade. Our data suggest that in most countries much of the public does not share the view that there is a crisis of local news – or at least that much of the information they value is being provided by other community actors accessed via search engines or social media.

But in a few countries, notably the UK and Australia, only a little over half say their needs are being met, suggesting that in these countries at least, local news needs are being significantly underserved. These are also countries where local publishers have taken a disproportionate share of job cuts. In countries such as Portugal, Bulgaria, and Japan a higher proportion of unmet needs are largely down to lower interest in local news overall, leaving aside the important role that local news can play in supporting democracy.

Overall, we find clear differences in terms of subject preferences by age and gender which help explain why some groups are engaging less with the news or avoiding it altogether. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to these issues but improving coverage of subjects with higher interest that are currently underserved would be a good starting point.

New formats and the role of audio

Publishers are also exploring different formats as a way of addressing the engagement challenge, especially those that are less immediately reliant on platform algorithms, such as podcasts.

In the last few years, leading publishers such as the New York Times and Schibsted have joined public broadcasters in trying to build their own platforms for distribution to compete with giants like Spotify, using exclusive content or windowing strategies to drive direct traffic. Legacy print publishers have been ramping up their podcast production, finding the combination of text and audio a good fit for specialist journalistic beats, and relatively low cost compared with video. In countries such as the United Kingdom, a strong independent sector is emerging with a range of new launches for politics and economic shows this year, as well as US spin-offs for popular daily podcasts such as the News Agents. Many of the most popular podcasts are now filmed and distributed via video platforms such as YouTube, further blurring the lines between podcasts and video. Across 20 countries where we have been measuring podcast consumption since 2018, just over a third (35%) have accessed one or more podcasts in the last month, but only just over one in ten (13%) regularly use a news one. The share of podcast listening for news shows has remained roughly the same as it was seven years ago.

Podcasts continue to attract younger, richer, and better educated audiences, with news and politics shows heavily skewed towards men, partly due to the dominance of male hosts, as we reported last year. Many markets have become saturated with content, making it hard for new shows to be discovered and also for existing shows to grow audiences.

Conclusions

Our report this year sees news publishers caught in the midst of another set of far-reaching technological and behavioural changes, adding to the pressures on sustainable journalism. But it’s not just news media. The giants of the tech world such as Meta and Google are themselves facing disruption from rivals like Microsoft as well as more agile AI-driven challengers and are looking to maintain their position. In the process, they are changing the way their products work at some pace, with knock-on impacts for an increasingly delicate news ecosystem.

Some kind of platform reset is underway with more emphasis on keeping traffic within their environments and with greater focus on formats proven to drive engagement, such as video. Many newer platforms with younger user bases are far less centred on text and links than incumbent platforms, with content shaped by a multitude of (sometimes hugely popular) creators rather than by established publishers. In some cases, news is being excluded or downgraded because technology companies think it causes more trouble than it is worth. Traffic from social media and search is likely to become more unpredictable over time, but getting off the algorithmic treadmill won’t be easy.

While some media companies continue to perform well in this challenging environment, many others are struggling to convince people that their news is worth paying attention to, let alone paying for. Interest in the news has been falling, the proportion avoiding it has increased, trust remains low, and many consumers are feeling increasingly overwhelmed and confused by the amount of news. Artificial intelligence may make this situation worse, by creating a flood of low-quality content and synthetic media of dubious provenance.

But these shifts also offer a measure of hope that some publishers can establish a stronger position. If news brands are able to show that their journalism is built on accuracy, fairness, and transparency – and that humans remain in control – audiences are more likely to respond positively. Re-engaging audiences will also require publishers to rethink some of the ways that journalism has been practised in the past; to find ways to be more accessible without dumbing down; to report the world as it is whilst also giving hope; to give people different perspectives without turning it into an argument. In a world of superabundant content, success is also likely to be rooted in standing out from the crowd, to be a destination for something that the algorithm and the AI can’t provide while remaining discoverable via many different platforms. Do all that and there is at least a possibility that more people, including some younger ones, will increasingly value and trust news brands once again.

Footnotes

1 https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/mar/26/instagram-meta-political-content-opt-in-rules-threads

2 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2024

3 While not necessarily a reliable indicator of underlying trustworthiness, such reliance on ‘realism heuristics’ also helps shape often high trust in television news versus other sources.

4 https://www.newsguardtech.com/misinformation-monitor/september-2022/

5 https://www.theguardian.com/media/2024/mar/26/tech-firms-poised-to-mass-hire-factcheckers-before-eu-elections

6 https://www.semafor.com/article/04/19/2024/tiktok-fight-in-kenya

7 https://wan-ifra.org/2023/11/ai-and-robot-writer-klara-key-todumonts-kolner-stadt-anzeiger-mediens-tech-future-as-it-switches-off-its-presses/

8 https://www.d-id.com/resources/case-study/radioformula/

9 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-023-02282-w

10 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/paying-news-price-conscious-consumers-look-value-amid-cost-living-crisis

11 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/trust-news-project

12 https://europeanconservative.com/articles/commentary/whos-verifying-bbc-verify/

13 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2024