In this piece

The future is feminist: lessons from journalists in Mexico and Argentina

A woman places flowers on an altar in memory of femicide victims before the Day of the Dead in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, October 31, 2021. The letters read "Not one less". REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez

In this piece

Femicide covered in a sexist tone | Covering criminalised abortion as gendered violence | The cost of covering feminist issues | New digital voices | Feminist leadershipJournalist Irene Benito recently covered the femicide of 32-year-old teacher Paola Tacacho. Tacacho was killed just 200 metres from Benito’s home in downtown Tucumán, Argentina: Benito heard the screams while she was working.

Tacacho was murdered by a former student who had stalked her for five years.

“It was a chilling case,” Benito told me. “The more I learned about the story, the more I felt the injustice of the case, and the more I needed to tell it.”

Journalist Irene Benito arrives at court on Dec. 21, 2021 Photograph: Soledad Dato/Supplied

Tacacho had gone to local authorities to file 13 complaints against him in that time, obtained a restraining order that he ignored, and finally took him to court. A judge rejected the case, citing a lack of evidence of harassment.

Women’s perspectives on this kind of story have historically been lacking in newsrooms, especially in Latin America. With so few women and LGBTQ people in the industry, their voices and impact in newsrooms continue to be marginalised.

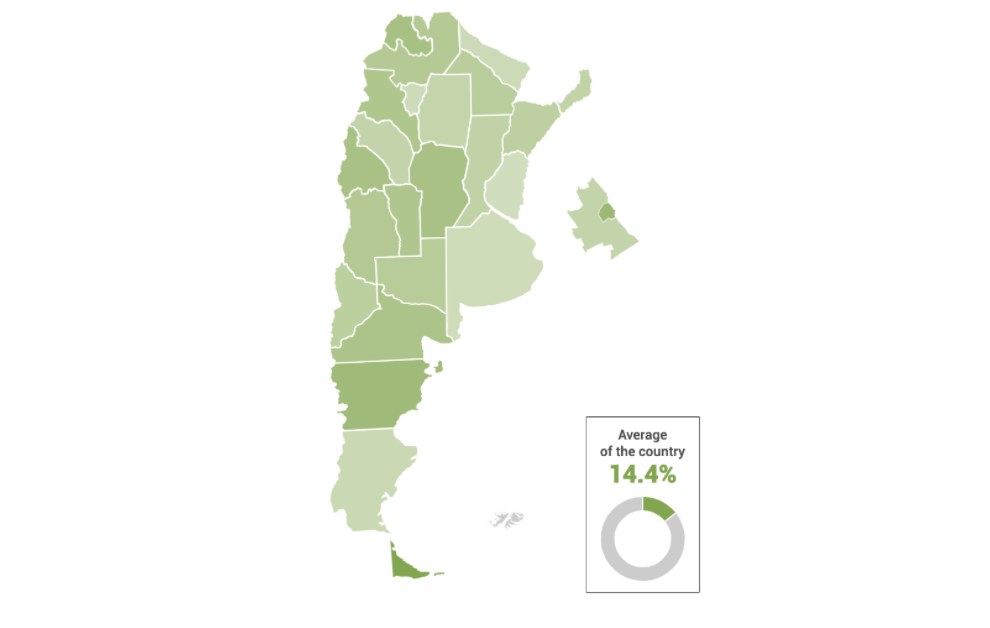

In 2021 the Forum of Argentinian Journalists (FOPEA), an organisation that advocates for journalists and press freedom, conducted the first country-wide study of local news deserts with funding from the Google News Initiative. With that data they analysed gender in leadership of local news outlets nationwide, creating the first directory of the 354 women who lead local newsrooms in the country. They found that 14% of local outlets are led by women and only 13% of all journalists surveyed work in a female-led organisation.

FOPEA’s survey of 2,464 news organisations in Argentina found female directors lead 354 (14.4%) of the news outlets

“The media are channels for disseminating women’s grievances, but we don’t look within. It’s as if we were far away from the demand for equality, equity and diversity,” said Benito, who was on the research team. She sees the research as a huge step forward in recognising the magnitude of the problem.

Benito found that while there are women who are thought leaders with influence in newsrooms, they are generally not in decision-making positions to lead teams within the newsroom. They take on different, informal leadership roles that are important – like moral leadership – but are not recognised as those who steer the ship. It is time for a conversation about gender inclusion in these newsrooms.

Femicide covered in a sexist tone

A scourge of femicides documented in Latin America over the past decade, likely due to increased reporting, has set the stage for activists to demand more sensitive coverage of extreme violence against women and LGBTQ people in the media.

Much of the coverage of femicide exploits gory details that harm ongoing criminal investigations, the victim’s family or their dignity post-mortem – including publishing naked photos of mutilated bodies, as was the case with Ingrid Escamilla in Mexico.

Escamilla’s 46-year-old partner stabbed and dismembered the 25-year-old in their home. Crime tabloid Pásala and Mexico’s La Prensa published disturbing graphic images of Escamilla’s naked bloody body on the front page with the headline It Was Cupid’s Fault, days before Valentine’s Day 2020.

Ten women are killed every day in Mexico. In Argentina, a woman is killed on average every 30 hours. The vast majority of femicides (killing of women because of their gender) are perpetrated with impunity by intimate partners, usually accompanied by sexual violence and often the result of ongoing abusive relationships.

Many feminist journalists in Mexico and Argentina describe mainstream news coverage of femicides as problematic, justifying perpetrators and blaming victims with headlines like, Blind with Jealousy, He Killed Her. Many news organisations print photographs of the clothing the victim was wearing when killed, implying that her choice of outfit played a role in her murder. Use of the passive voice is also common, deflecting guilt from the perpetrator and normalising violence as something that occurs rather than a criminal act that is perpetrated, by saying “she was killed” rather than “he killed her”.

Publishing graphic photos of Escamilla post-mortem earned the tabloids viral levels of traffic and sparked anger among hundreds of women who demonstrated following the controversial coverage, marching to the La Prensa newsroom and destroying several vehicles belonging to them.

The case represented a flashpoint in the intersection between extreme violence against women and sexist news coverage that exploits trauma as clickbait.

Ingrid’s Law was approved in Mexico in February of 2021. It is a set of legal reforms which seek to protect the victims of femicide from having their photos widely distributed. The reforms introduce criminal charges of three to six years of prison or fines for anyone who distributes photos, videos or documented evidence of murder victims.

Covering criminalised abortion as gendered violence

Feminist movements in Mexico and Argentina like Ni Una Menos (Not One Woman Less) and Marea Verde (Green Wave, a movement for safe and legal abortion) have gained traction over the past several years.

With feminist activism confronting the mainstream cultural climate, the journalism industries in Mexico and Argentina are grappling with what accurate non-sexist coverage means and how to achieve it. When most newsrooms are run by men and violent culture is dominant in society and in the workplace, the problem of skewed coverage is difficult for many to see because sexism is normalised and internalised.

Debates around abortion are a perfect example. Unlike cases of femicide, which are perpetrated with close to absolute impunity, criminal charges are brought against women who have abortions and even against those who suffer obstetric emergencies like miscarriages in Mexico. Feminist journalists and activists are now framing the lack of legal abortion as a form of gendered violence.

Activist from "Marea Verde" take part in a performance to film a message to spread awareness during the International Safe Abortion Day in Mexico City, Mexico September 28, 2019. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso

In the investigation series Cuando parir es un delito (When Giving Birth is a Crime) Katia Rejón and Lilia Balam reported on the experiences of young women and teenagers who miscarried and were later charged with homicide. The investigation explored how a lack of training in gender sensitivity (and a lack of knowledge of female biology) results in legal decisions being made based on faulty evidence.

In Mexico over 3,600 criminal complaints were filed for the crime of illegal abortion between 2010 and 2020 according to GIRE, a Mexican reproductive rights group. Within that same timeframe, 380 people were criminally tried and 142 were sentenced.

Due to lack of sexual education, many don’t know that they are pregnant until miscarrying and they are then accused by medical staff and prosecutors of committing a crime. Every day in Latin America, girls between the age of 10 and 14 give birth – the vast majority having been raped.

The reframing of issues like these is pushing the boundaries of conventional journalistic norms of objectivity, replacing them with human rights advocacy frameworks that help contextualise complex issues in news coverage.

Activism and journalists reporting on the issue has led to recent policy changes in both countries. Argentina legalised abortion in the first 14 weeks of pregnancy in December 2020. In Mexico abortion has been decriminalised, after the country’s Supreme Court declared that abortion is not a crime in September 2021.

The cost of covering feminist issues

Reporting on abortion does not come without cost, and reporters who cover it are often harassed. Katia Rejón, a young journalist in Mérida, Mexico was the target of so-called pro-life groups after reporting on abortion and verifying that group members had lied about facts.

“There is a hostility for touching those kinds of topics, but not only topics of gender, also human rights and the indigenous community,” Rejón told me.

She was the subject of a public attack when Jorge Álvarez Rendón (the Chronicler of the city of Mérida, a man whose books she’d read as a student), wrote a public letter to her on his Facebook page, insulting her credibility as a journalist and her looks.

These kinds of cases cast a shadow over female journalists as they do their job.

Raised in the school of journalism that values objectivity as a core principle, Rejón began reporting stories involving obstetric violence, menstruation, the #MeToo movement and street harassment.

“At some point I understood that feminism wasn’t just something that served me as a person, as a woman, but also my work. Because these were subjects of social interest. Gendered violence in Mexico is outrageous. We can’t cover that news without considering that there is a whole system underneath it,” said Rejón.

Rejón represents a new generation of feminist journalists creating their own content through independent nonprofit digital publications. Her magazine Memorias de Nómada, started as a blog when she was 19 and now has a reach of up to 20,000 views per month focusing on cultural content, including the indigenous Maya population in the Yucatan region.

Mexican journalist and coordinator of the International Network of Journalists with Gendered Vision (RIPVG) Rosa Maria Rodriguez Quintanilla had to relocate out of her home state of Tamaulipas to Nuevo León because of threats against her and her family. Her home state has seen growing violence and several local journalists have been murdered.

“Now I’m conscious about what I experienced, but when I lived in my state I wasn’t aware of the violence I was experiencing every day,” Rodriguez Quintanilla told me.

At least seven in every 10 journalists in the country have received some type of threat or attack, Rodriguez Quintanilla said, adding that it’s never just one incident; the constant repetition is a key aspect of how the violence works.

“This time we left because the threats were against my children,” she said.

Mexico has a 99% impunity rate for crimes against freedom of expression and is one of the deadliest places in the world to be a journalist.

To make matters worse, authorities often minimise threats received via social media, or say that they’re unable to investigate. Social platforms like Facebook and Twitter do little to intervene. Even when threats of murder are shared on Facebook groups with thousands of followers, where people’s identities are exposed, like in Rodriguez Quintanilla’s case, results are nil.

Rodriguez Quintanilla credits CIMAC with supporting her during the abuse. CIMAC is the most widely recognised feminist digital publication in Mexico, which many see as the pioneers of feminist journalism in the country and the first organization to document press freedom through a lens of gender.

New digital voices

It’s not all bad news online: feminist journalists in Mexico and Argentina are using the internet to network, launch new initiatives, and reach new audiences. In Mexico, platforms like Memorias de Nómada and EsParaMiTarea are thriving. In Argentina, LATFEM is a digital publication with highly successful reach and engagement that has published a variety of investigations.

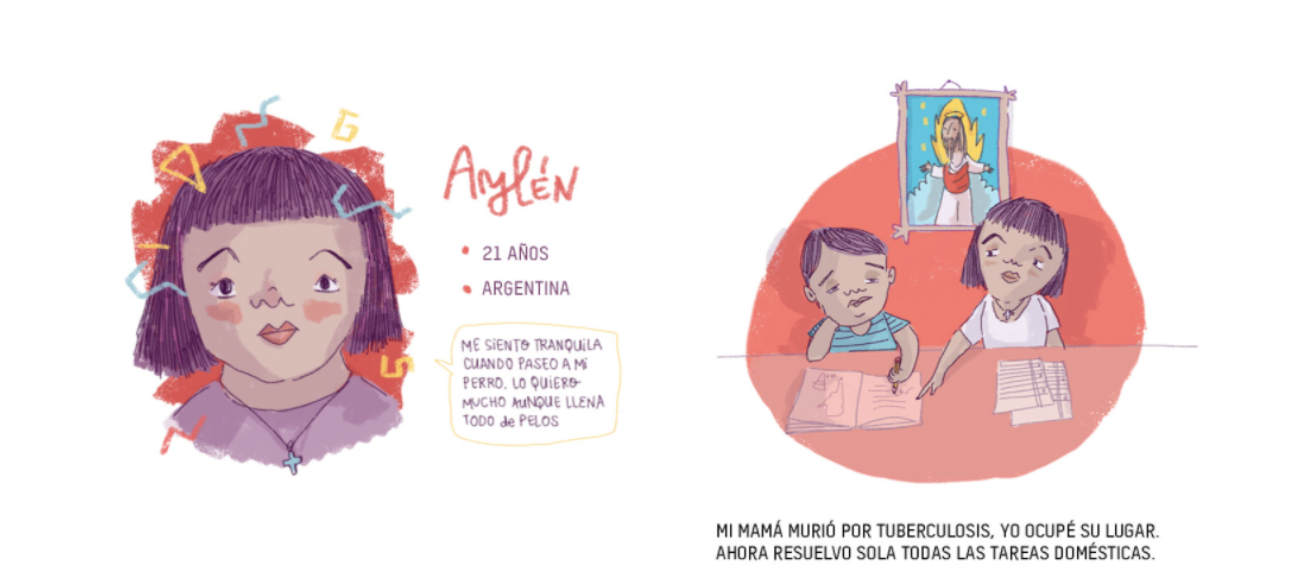

The organisation uses innovative methods to show the results of their investigations: Cuarantenials used illustrations to provide a feminist perspective on stories about young people in Latin America coming of age during the pandemic.

Screenshot from LATFEM’s Cuarentenials series, which illustrated the experiences of young people in lockdown. Illustrations by Kiti & Seelvana

The founders and journalists of LATFEM are journalists who come from activist backgrounds involved in feminist organising in Argentina. Founder Flor Alcaraz describes 2015 and the Ni Una Menos movement as a before-and-after moment which marks the era that took feminist activism mainstream in Argentina, and when she personally became comfortable calling herself a feminist journalist.

Though both LATFEM and Memorias de Nómada in Mexico are successful in terms of audience engagement, innovation and originality, both have struggled with funding to sustain their efforts.

While they do generate revenue through their workshops on gender, through collaborations with other nonprofit organisations, or by educating young journalists, neither receives any funding to do journalistic work. This means all their writers and staff work on a voluntary basis and have day-jobs to support themselves. Because they are both mission-driven organisations, unwilling to compromise their values for funding, their work for these outlets remains a passion project.

Both Rejón and Alcaraz are members of international networks of journalists which have helped support their work by connecting them with like-minded journalists throughout Latin America, like the Red de Periodistas Feministas de Latinoamerica y el Caribe, the Latin American Network of Young Journalists and Coalición LATAM, a group which provides mentorship to organisations like Memorias de Nómada.

“I think that it’s really helped us a lot to have alliances in other states [and] in other countries to help us legitimise our work. We are investigating topics that weren’t being touched before,” said Rejón.

These networks have brought journalists together for transnational investigative projects like Violentadas en Cuarentena (Abused in Lockdown). The project was a collaboration of over 66 people including reporters, fact-checkers, illustrators and translators in 19 countries, and won a Google News Award.

Feminist leadership

Feminist journalists like Miriam Bobadilla and Alejandra Benaglia of Argentina see their work as making the industry more feminist, not only in terms of equitable representation, but also in the styles of leadership and how the industry is organised.

Both Bobadilla and Benaglia are part of the RIPVG (International Network of Journalists with a Gendered Vision): a network that connects journalists with online events, publishes research around gender in the media, and hosts educational workshops to teach journalists new methods to incorporate gendered perspectives into their work.

Some are starting to use labour unions to advocate for women’s advancement in the newsroom. FATPREN, the Federation of Press Workers of Argentina, is a union that has an agenda which includes a committee on gender. The group fought for and secured sexual harassment and gendered violence protocol in 2016.

The female leadership sees their work as combating the hypermasculine culture of both unionism and the news industry so that women are included in meaningful ways.

Legacy media around the world is beginning to view gender coverage as profitable and starting to take notice, according to Aimée Vega Montiel, a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Major publications like the Guardian, El País, and Mexican publications like La Silla Rota and Reforma are starting to incorporate human rights coverage of women in some of their reporting.

Spanish editions of the Washington Post and the New York Times have also published content focused on gender and human rights in their Opinion sections. Flor Alcaraz, LATFEM founder, was recruited by the Washington Post for her expertise in feminist content in Argentina. Other news outlets in Latin America like La Silla Rota in Mexico and Página 12 in Argentina are creating gender verticals to speak to the growing demand for content. Página 12 and Tiempo Argentino also use inclusive or gender neutral language, which is an editorial decision that Bobadilla and Benaglia said other mainstream publications don’t incorporate in their coverage.

Women, LGBTQ people and their allies within the industry are organising and building power through traditional methods like labour unions, as well as entrepreneurial and investigative projects. They are pushing to improve newsrooms slowly and in the face of resistance. But the changes being implemented are not moving in pace with the cultural moment that activists have forced into existence.

Much like the groundswell of feminist activism that inspired major policy changes for gender equity, few can predict the fervor or force with which the situation will progress.

The only certainty is that the male gaze has dominated the journalism industry for as long as it has existed. Anyone interested in accurate news coverage and newsroom equity can see a long overdue change on the horizon. The future of journalism is feminist.

A more detailed version of this report is available for download as PDF below.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time