What Russian audiences may lose if Trump shuts down Radio Free Europe

A view shows the now-closed newsroom of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) in Moscow in April 2021. REUTERS/Evgenia Novozhenina

In early April satellite television viewers relying on news from outside the Kremlin’s information space were in for an unpleasant surprise: Instead of Current Time, a news broadcast by US-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), they saw a red screen with an ominous message. The satellite transmitting RFE/RL’s much-watched format into Russia was switched off by Donald Trump’s administration in its effort to shut the outlet down, together with Voice of America and Radio Free Asia.

Trump’s plan left thousands of journalists in limbo and a void that authoritarian regimes are trying to fill. But it could also strip Russian speakers and other RFE/RL audiences of a vital resource.

“In most countries we work in, people don't have access to free or fair press,” RFE/RL editor-in-chief Nicola Careem told me during an interview late last year. “We are fulfilling what I would call lifeline journalism for people across our broadcast region,” which encompasses 27 languages in 23 countries including Belarus, Bulgaria, Azerbaijan and Pakistan.

According to Careem, who was appointed editor-in-chief in July 2023 and also serves as Vice President, reaching Russian-speaking audiences inside Russia and elsewhere has been a “huge strategic priority” for the broadcaster.

“We are the only international media to provide a 24/7 television channel in Russian for audiences outside Russia as well,” Careem said. On an average week, she adds, RFE/RL programmes reach around 9% of Russia’s adult population, roughly 10 million people. According to RFE/RL, the station also reaches 10% of Iranians and 25.8% of Ukrainians every week. With its radio, digital and television programs, RFE/RL says it reaches close to 50 million people every week in their own languages and in 23 countries, from South Eastern Europe over the Caucasus, Central Asia and the Middle East to South Asia.

During my conversations with RFE/RL journalists at its 2-year-old Riga hub late last year, it became clear how much people in the broadcaster’s reporting area depend on its journalistic offerings and how much institutional knowledge, resources and risks it takes to operate in repressive environments. This suggests RFE/RL is difficult and, in some areas, perhaps even impossible to replace.

“With RFE/RL's closure, local media won't be able to fill in that huge void,” CPJ Europe and Central Asia Program Coordinator Gulnoza Said told me. “But the state propaganda machine will be able to strengthen its propaganda, disinformation and misinformation, including propaganda of the war by the Kremlin since the authoritarian governments have resources amid the lack of accountability.” Said worked with RFE/RL's English-language newsroom in the early 2000s.

Based on my conversations with four reporters and media managers from RFE/RL, this article explains how the organisation reaches Russian-speaking audiences from Riga, how they manage to report stories very few others can, and what audiences in authoritarian societies stand to lose if Trump’s team succeeds in severing this critical lifeline.

RFE/RL: a very short history

Headquartered in the Czech capital Prague and in Washington, DC, RFE/RL’s yearly budget of $142 million, over 1,300 staff and more than 20 bureaus make it one of the largest news organisations in the world.

When Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty began broadcasting mainly from Munich in 1950 and 1953, respectively, they were a clandestine US intelligence effort aimed at infiltrating the Iron Curtain. In 1971, five years before the merger of both ‘radios’, as they were commonly called, the CIA stopped funding RFE/RL. After more than two decades funded by a Congressional appropriation, the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM) started bankrolling the broadcaster in 1995, the same year it moved its broadcasting center to Prague.

RFE/RL survived calls to end its operation after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and expanded its coverage to newly independent states like Kyrgyzstan. The 1990s saw RFE/RL’s Russian Service (Radio Svoboda) open a bureau in Moscow after its coverage of the failed 1991 military coup against Mikhail Gorbachev. The outlet closed its language services in the Baltic states and the countries in the Soviet block in the early 2000s.

During the first two decades of this century, RFE/RL launched several Russian-language alternatives to Kremlin-controlled media in response to Russian aggression and disinformation campaigns. They included a programme in Georgia after the 2008 invasion, the Crimea.Realities and Donbas.Realities projects in 2014 following the first iteration of the war in Ukraine, and the now 24/7 Russian-language TV and digital network Current Time, also in 2014. According to RFE/RL, almost 9% of Russians aged 15-24 consumed RFE/RL’s flagship Russian-language channel every week in 2023.

In 2017 and 2024, respectively, the Russian Federation declared RFE/RL a ‘foreign agent’ and an ‘undesirable organisation’, severely hampering its journalists’ ability to do their work. Amid democratic backsliding, RFE/RL returned to Romania and Bulgaria as well as to Hungary in 2019 and 2020, respectively. One year later, the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan forced RFE/RL to close its local bureau and evacuate hundreds of staff members.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 led to RFE/RL suspending its operation in Russia and relocating its Russian Service and Current Time journalists to the Latvian capital Riga, where it opened its new reporting hub in 2023 along with an office in Lithuania.

What makes RFE/RL unique

“Riga was already becoming a hub for Russian journalists in exile, so it made sense for us to be part of the diaspora there,” said Andrey Shary, director of RFE/RL's Russian Service, referring to the flurry of Russian reporters and Western media outlets relocating their staff from Moscow to Riga. “The thinking over the last few years has been to keep [these people] as close as possible to their markets and to their audiences.”

When asked what makes RFE/RL indispensable, Shary pointed to the multi-platform Russian-language content it’s been producing from and about Ukraine, such as its award-winning coverage of the first hours of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

“Our frontline reporting is unique for the Russian-language market,” claimed Shary, who joined RFE/RL in 1992 and served as the Moscow bureau’s editor in chief in 2002-2004 and as director of RFE/RL’s organisation in Russia in 2021-2023. “Nobody else has it to such an extent. We also make Russian-language content for Ukraine. Serving it in a way so it’s consumed by both Russians and Ukrainians requires an extremely technical and fine-tuned balance, but it's doable.”

Another distinctive feature of RFE/RL are its region-specific programs that broadcast in local languages. In Russia alone, RFE/RL has six of these formats, including Sibir.Realii (Siberia Realities), Sever.Realii for residents of northwestern Russia and Kavkaz.Realii (Caucasus Realities), which broadcasts in Russian and Chechen, a language spoken by less than two million people.

“We have very different audiences, and each of our many teams serves a different one,” Shary told me. “Their content might be similar, but they all focus on local issues, too.”

According to Shary, Russia’s population is roughly divided into three groups: hard-to-reach Putin supporters with a closed worldview; anti-Putin people, which Shary said are RFE/RL’s core audience; and an estimated 50% of Russians who are at least open to consuming non-Kremlin media. It is the last group in particular that RFE/RL tries to reach with its Russian-language content.

Reaching Russians from Riga

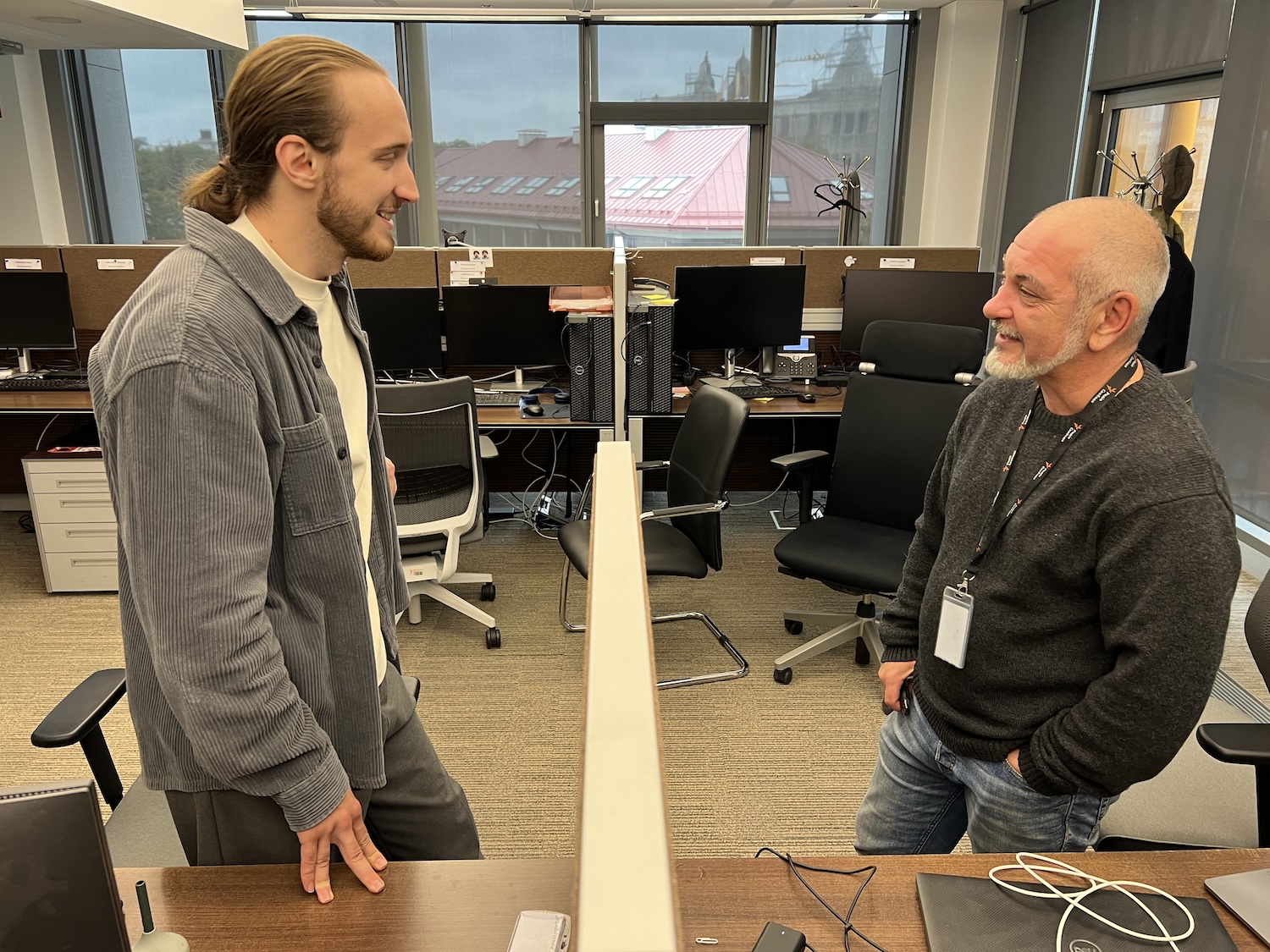

Shary oversees around 60 journalists who work for the Russian Service, 19 of whom are based in Riga, RFE/RL’s third-largest office. They are all Russian nationals who went into exile in the days and weeks after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

One of them is 25-year-old Artyom Radygin, who co-anchors Facing the Event, a weekday evening news show that analyses the most important events coming out of Russia. Together with two Georgia-based reporters, two producers and up to two video editors, Radygin shows how political and nonpolitical developments affect ordinary Russians’ lives and fact-checks Kremlin statements.

“In the comments under our videos, I frequently notice how people – even our regular audience – pick up the narratives of Russian propaganda,” Radygin said. “So it's even more important to be the beacon of light for the audiences who are being devoured by this propaganda. It really devours their minds. It's coming from everywhere.”

According to Radygin, an episode of Facing the Event illustrates this quite well: the one in which they dissected Russia’s state budget for 2025, for which the Kremlin hiked defense spending by 25% compared to 2024.

“We invited two economists to discuss the budget from the perspectives of the Russian citizens,” he said. “One prepared package summarised how much money will be spent on Putin's priorities like military needs. The second package covered how the authorities and the media cherry-pick only positive parts of the budget. According to Kremlin propaganda, social security would be increased and disabled people, for instance, would get more money. But they did not mention inflation. So we tried to show how Russians will actually lose money.”

Facing the Event is a 27-minute format and is broadcast live on YouTube, on the radio, on the website and on Current Time. The programme is also repackaged for Telegram, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter/X.

Since Radio Svoboda is cut off from television and radio frequencies, Russians inside Russia can only watch the live news show via virtual private networks (VPNs) or YouTube, which has long been a fixed part of many Russians’ daily routines. Although they haven’t officially banned it, Russian authorities have slowed YouTube down from last summer as they regard it as a way to access antiwar content.

According to anchor Radygin, newscasts used to get up to 400,000 views before the loading speed was throttled, compared to up to 50,000 views now. What hasn’t changed, he said, is the approximately 40% of viewers that make up their returning, loyal audience. Echoing Russian Service director Shary, he says it’s the 60% newcomers they focus on.

“These newcomers might be Putin supporters or even people who support the war. I can clearly see it in our analytics: the vast majority of that audience comes to us after having watched some Kremlin-admiring YouTube channels.”

Equipped with this knowledge, Radygin said, he and his team try to “tone down” their language, especially concerning the war. “Some newcomers might still not realise what’s been happening,” he explains. “So if you are too explicit, you will just scare them away. Of course we cover atrocities committed by Russian soldiers. But we also shift the focus to the perspective of the Russian citizens by showing them how the actions of the Russian military in Ukraine harm Russia’s economy and Russian social life in the long term.”

The risks of reporting on Russia

The Riga hub is also home to digital-first video news project Current Time Baltics, whose target audience are the large Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia.

Until recently, RFE/RL’s ‘digital innovation lab’ was another unit that had staff working out of Riga. The lab develops tools and strategies to circumvent online censorship that include so-called mirror sites – copies of websites hosted on a different server to ensure sites remain available –, downloadable apps with built-in VPNs, which hide IP addresses and keep users anonymous (more than half of Russia’s Internet users reportedly at least know what VPNs are); and transmitting data through radio waves (satellite datacasting).

People in Russia caught sharing, liking or commenting on RFE/RL content have been facing fines or imprisonment since the broadcaster has been declared an ‘undesirable organisation’. This severely restricts its ability to report on the ground.

“We have our sources and possibilities to get content out of Russia,” Russian Service director Shary said, adding that the situation is “extremely difficult” nonetheless.

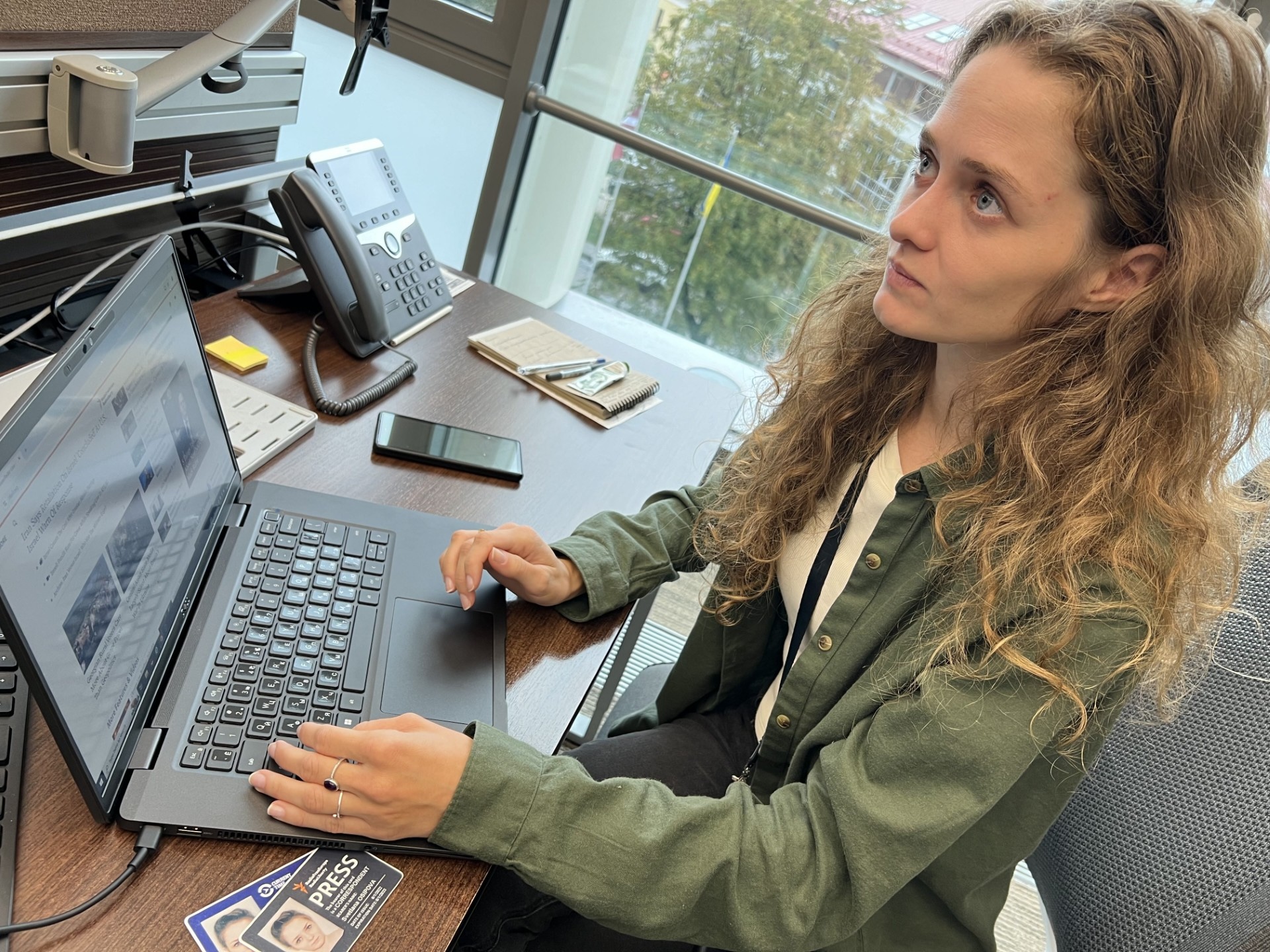

For RFE/RL’s investigative journalists like Svetlana Osipova, contacting sources in Russia is a sensitive and risky undertaking.

“We have a big responsibility when we contact someone in Russia,” Osipova told me. “It’s a crime to create material about the war [in Ukraine], as is talking to an undesirable organisation like us. I'm also afraid to text people in Russia in [social network] VKontakte, because security services can read everything. It's already a crime if this person responds to me, even if they wouldn’t want to talk to me.”

Osipova is one of 15 investigative reporters who work for Systema, an over two-year-old unit that publishes exclusive investigations about Russia on YouTube in addition to smaller investigations disseminated on Telegram.

When RFE/RL was labeled an ‘undesirable organisation’, Osipova was making a video about conversion therapy for LGBTQ people in Russia and had to contact each interviewee to make sure they’re still onboard: “One person no longer wanted to participate, but when we offered to change her voice and blur her face, she agreed. It saved our film.”

Facing the Event anchor Radygin said one of the biggest risks is telling people’s stories. “Even if you find a freelancer in Russia who decides to make a good piece, the person who appears on your video is under a great threat. So you have to blur, make people unrecognisable, change their voice, everything; and even after that it does not guarantee their safety.”

“You cannot be completely safe”

Even high-profile journalists in exile like Radygin and Osipova haven’t been safe due to the ‘undesirable’ designation, according to editor-in-chief Nicola Careem.

“We are very aware of the heightened risk that we face,” Careem said. “Being labelled ‘undesirable’ criminalises every single one of our journalists. Our Russian citizens are unable to travel back to Russia. Imagine never knowing when you can go home again, never knowing when you might be reunited with your loved ones or what the future holds for you. It's profoundly traumatic.”

To help them protect themselves as much as possible, RFE/RL offers staff resources such as digital safety and hostile environment training. But Russian exiles are being surveilled and worse. Journalist Elena Kostyuchenko was likely poisoned on a German train in 2023 and Navalny ally Lenoid Volkov was attacked in Lithuania last year.

“You cannot be completely safe. It's daunting and depressing,” Radygin told me. “I do not pay anywhere in my name. I do not take a taxi to my home. I do not order any deliveries to my home.”

According to CPJ’s Said, Russian authorities have targeted RFE/RL's Russian Service throughout its 72-year history. “Killings, imprisonments, harassment – nothing was beyond the government's arsenal of tools used to silence journalists.”

At present, RFE/RL has four journalists behind bars in Russia, Belarus, Azerbaijan and Russia-occupied Crimea. Although the Trump administration secured the release of Radio Liberty journalist Andrey Kuznechyk from Belarus in February, its executive order to dismantle the outlet’s parent organisation USGAM could have dire consequences for the fight for these journalists’ release.

“If your broadcasts hadn’t covered my plight, I would have remained in prison for a longer time than I did,” said Vaclav Havel, the former Czech President who invited the broadcaster to Prague in the early 1990s.

With the station’s future under threat, hundreds of Riga- and Prague-based journalists from Russia, the Middle East and elsewhere, who are unable to work freely in their home countries, face a time of uncertainty and fear.

In contrast to Prague, none of the 75 staff in Riga had been affected by furloughs at the time of this writing, according to RFE/RL. But the forced savings have taken a toll on operations in Riga nonetheless: For instance, anchor Radygin says he’s been unable to commission the two Georgia-based freelance reporters who regularly work for Facing the Event.

“For my team it is a tremendous loss, because these people did exclusive reporting in Russia,” Radygin explains, adding that he’s trying to find external funding so that he can hire them again.

If the Trump administration succeeds in shutting the radios down completely it would be a blow to global press freedom, depriving millions of Russians and other people in RFE/RL's broadcast region of fact-based reporting.

Russian Service director Shary believes in the broadcaster’s resilience: “We have been battling Kremlin propaganda for 70 years. We used to do it during Soviet times when Radio Svoboda was jammed, and we survived and we won. So now is another epoch, but we’ve fared better than others because we have this tremendous experience.”

Editor's note: The percentage of Ukrainian population reached by Radio Free Europe is 25.8%, and not 40% as a previous version of this article said. The Riga hub opened in 2023, and not in 2024 as a previous version of this piece stated.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time