Reporting elections on the frontline of the disinformation war

How mission-driven news organisations in three unstable democracies have worked to combat ‘information pollution’

National elections in South Africa, the Philippines, and in India have tested the disinformation-busting strategies of three digital-born newsrooms on the frontline of the fightback against disinformation. At the Daily Maverick in South Africa, Rappler in the Philippines, and The Quint in India, a combination of network mapping and analysis, audience-engaged fact-checking verticals, and traditional investigative reporting, along with community-focused issues and policy analysis, has been driving coverage. Underpinning these strategies was a common sense of democratic mission associated with accountability journalism.

In the lead up to the elections, Senior Research Fellow Julie Posetti spent a month embedded within these newsrooms for the Reuters Institute’s Journalism Innovation Project observing their strategies for combating disinformation and election reporting preparation up close. During this period, Rappler’s Executive Editor Maria Ressa was arrested for the second time in the context of a concerted campaign by the Duterte government to chill Rappler’s reporting, and conflict loomed on the border of India and Pakistan in the aftermath of a terrorist attack, which dramatically increased the ‘pollution’ in the information ecosystem being trawled by The Quint. At the Daily Maverick in South Africa, the threat of violence associated with the country’s impending elections was a serious concern as racial tensions escalated.

Countering disinformation as an innovative, mission-driven journalistic defence of democracy

Each of these news outlets demonstrated a deeply held and passionately espoused commitment to what they separately referred to as their ‘mission’ – closely tied to their self-identified role as ‘guardians’ of democracy and open societies which has caused them, they say, to be targeted by political actors seeking to chill media freedom and critical reporting in their countries.

Directly connected to this shared sense of mission is the commitment of the three news organisations to innovatively countering state-linked disinformation campaigns which involve the direct targeting of their outlets and reporters, and threaten to swamp credible journalism, while damaging trust in the ‘fourth estate’. Among the concerns expressed by many of the interviewees participating in our research was the notion of ‘trolls’ or ‘cyber armies’ usurping the gatekeeper role traditionally occupied by the free press in open societies.

These are not trends limited to fragile democracies in the Global South. However, the potential impacts in these countries are arguably more dangerous, with the threat of physical violence often linked to orchestrated and/or state-sponsored disinformation campaigns that begin online.

The Rappler Effect

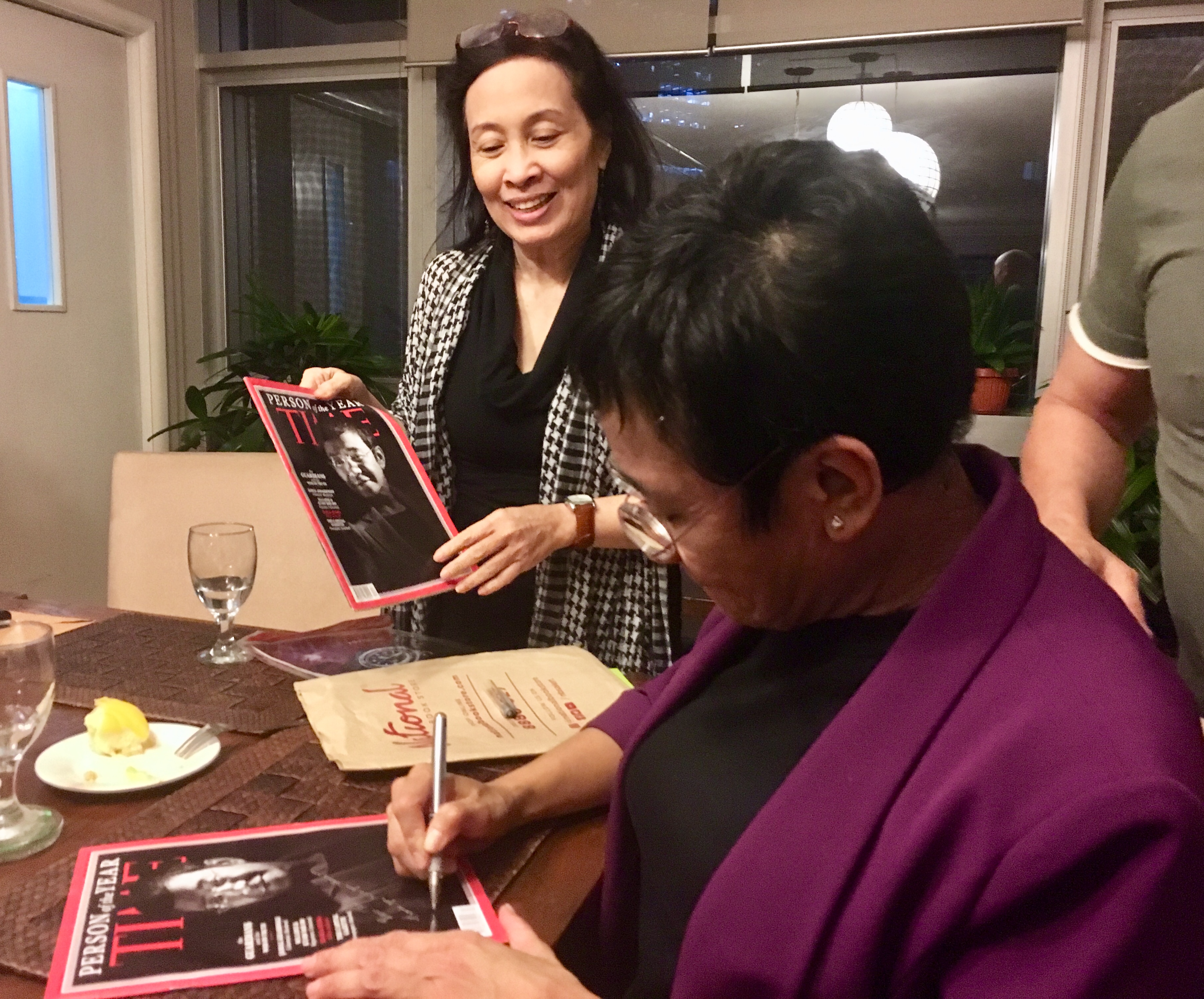

In the case of Rappler CEO and Executive Editor, Maria Ressa, this democratic mission led to a slew of international press freedom and investigative journalism awards and designation as a Time Magazine Person of the Year. The threats posed to news organisations by the disinformation campaign driven by a populist Philippines government range from what Ressa calls the “weaponisation of the legal system” against independent news outlets and editors (through spurious cases and defamation actions designed to limit their capacity to operate and chill their reporting), to journalism safety threats involving the targeting of reporters through online harassment. These are campaigns which Ressa said demand to be called out as attacks on democracy and exposed through reporting:

"Frankly, for the government to be using this crap means they don't care about the future of this nation, because not only are they dumbing people down, they're even misleading themselves. It's really ridiculous. It's a scorched earth policy. They can gain power for a short period of time, but they will kill our country."

But the concerns expressed by the Rappler interviewees were directed at both state actors and the platforms. In the Philippines, Facebook’s role in enabling the scale of the disinformation threat, in denying gatekeeper responsibility, and in failing to defend news organisations and journalists against prolific, targeted online harassment, was also highlighted by Ressa:

"If I go to jail, it's partly Facebook's fault. They've enabled this. News groups lost their gatekeeping powers…the new gatekeepers allowed the poison to come in. I mean, it's the worst of human nature that it’s rewarded. I think this is part of the reason I'd pushed really hard and one of the reasons I'm helping in the clean-up of this because…information is power. That's the basic foundation. That's why journalists are important, right? We did our jobs as gatekeepers, the new gatekeepers allow lies to create toxic sludge that people believed."

A Maverick defence of South Africa’s young democracy

In South Africa, Daily Maverick journalists identified as being committed to a form of accountability journalism that defends against disinformation as a service to a democracy. The country’s recent past as a racist authoritarian state looms large as a motivating force, as articulated by Associate Editor, Ferial Haffajee:

"My mission has always been quite a simple one because I grew up under apartheid. Freedom is intrinsically and fundamentally important to me. Protecting our democracy is a vital part of my being, what drives me as a journalist."

The state-linked disinformation campaign associated with the #GuptaLeaks ‘state capture’ investigation, which helped bring down the corruption-plagued Zuma Government, woke South African journalism up to the local manifestation of a global problem. “It has shown us that South Africa is not immune from that kind of… conscious, funded, driven disinformation,” Daily Maverick’s senior political reporter Marianne Mertens said.

Stoking racism and seeding disunity along racial lines in a country still recovering from apartheid was a notable feature of the disinformation campaign seeded by the British PR firm Bell Pottinger under contract to President Zuma’s son. The stated objective was to “turn the tide of the country’s trajectory in the long term… the language and psychology used will be crucial”, and invoked South Africa’s fear of Zimbabwean-style assets seizure. Subsequently, the populist political party Economic Freedom Front applied similar disinformation tactics, targeting female journalists – notably several Daily Maverick reporters – in a campaign designed to chill their critical coverage.

The Quint’s ‘post truth’ mission

In India, populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his BJP party have been associated with disinformation campaigns targeting news organisations and journalists critical of Hindu nationalism, with gendered online harassment of journalists a major feature of these campaigns. Journalists at the Quint have been among those subjected to such abuse, but this has served to strengthen the organisation’s commitment to combating organic and orchestrated disinformation campaigns as an expression of a democratic mission to provide audiences with accurate, reliable information. This is what Editor-in-Chief Raghav Bahl described as ‘public service journalism’.

The Quint’s journalists described their roles as ‘truth tellers’, ‘fact-checkers’, and ‘myth-busters’. While acknowledging low levels of trust in news media, in part caused by concerns about misinformation, they expressed a belief that The Quint was seeking to address a void. “Many people don’t trust mainstream media. That is when they come back to us. We're filling that gap,” Malavika Balasubramaniam, editor of Quint’s fact-checking vertical WebQoof said.

But there is a deeper disinformation challenge being taken up by The Quint in the service of a democratically-connected journalism mission, described by Senior News Editor Jaskirat Singh Bawa as India’s “biggest challenge”. It’s the reality that many people don’t want to believe the truth:

Unfortunately, we are in a post-truth world. A substantial number of people are not comfortable enough to know what the facts are. They just want the narrative to be based on what they already believe in. That's been a very tough issue to counter. Do you take them head on? Do you tell them, "No, you're wrong."? Or do you try and involve them in a dialogue, and try and make it more participative, and try to explain how damaging that can be to the social fabric, to the welfare of society in general?

Many of the editors, CEOs, and journalists interviewed from the three outlets we studied identified themselves as media freedom activists and advocates, invested in the preservation of democracies under threat, along with their news organisations’ missions. Importantly, too, they connected this shared mission with their audiences, who were identified as being ‘joined in the cause’.

The recent history of these countries, which involves revolution, political violence, and the overthrow of corrupt dictatorships in pursuit of democracy and independence (movements in which journalists and news organisations actively participated) means that the journalism traditions are informed by living memories of societies where the press was shackled and journalists were jailed for critical reporting. Journalists in the Philippines, South Africa and India are also at greater risk of being targets of violence and imprisonment in their countries based on global press freedom rankings. As such, the rise of digital era disinformation (with the power for high-speed viral amplification via social platforms) that threatens democracy is both a particular concern, and one which the news organisations studied have had to ‘pivot’ to address.

Election reporting strategies from the frontlines of the ‘disinformation war’

Paramount in the minds of editors at the three news organisations we examined was the need to defend against and combat ‘information pollution’ during election campaigns. One way they aimed to do this was to increase voters’ sense of political agency through community-engaged election coverage.

There was also a sense of ‘returning’ election coverage to the voters. “We, not just Rappler, but the Philippines has forgotten why we always say that the voters are powerful during elections, [which] are a measure of whether Democracy works in your country. The media’s responsibility… is to give people the room and the chance to think the issues through,” Rappler’s News Editor Miriam Grace Go said. “Are we contributing to giving people the space to think before voting?”At the Daily Maverick, Johannesburg Managing Editor Jillian Green planned to shape the outlet’s election coverage according to a ‘citizen’s agenda’. “This election should really be driven by the voters and their concerns about South Africa ,” she said. For example, a series called The Voter was seen as “a chance to really get out to the small towns and villages so that social justice drives the narrative rather than corruption,” Associate Editor Ferial Haffajee said. “We have to return the voice to people.”

In India, The Quint journalists were well-accustomed to the pace of a “crazy election cycle”, Senior News Editor Shelley Walia said. “We have five to six elections every year… you can actually pick up every (Indian) state and treat it as a country.” Like the Daily Maverick, The Quint intended to focus on informing people about their rights and policy implications for the issues fundamentally concerning them.

When everyone is a publisher

Nonetheless, the landscape has permanently changed. The Quint’s Social and Community Editor Sohini Guharoy acknowledged at the outset that India’s election would be “very difficult” because of the information and opinion overflow. “This year everything is out there, everyone has an opinion, and they do not need to pay to put their opinion out. You're just a Facebook status away, you’re just a Twitter status away, it is no longer even limited to your friends group,” she added, alluding to the well-documented viral spread of disinformation on WhatsApp in India.

Gemma Bagayaua-Mendoza at Rappler agreed. “The space that we are living in is really something that can be used … for manipulating people, and propaganda. “The reality is that these platforms are also today’s public communication spaces.”

Fine-tuning fact-checking

Covering the elections in a less traditional, more innovative way was one rule of thumb for all three news organisations studied – but fact-checking and verification processes were prioritised as foundational processes. Historically, Rappler’s research team would focus on election day polling data – which now generates content and potentially monetisable outputs. This election, Rappler made a deliberate effort to avoid ‘story-fying everything’, News Editor Miriam Grace Go said. “We make harder decisions every day about ignoring press releases, or antics, or statements by the president”. For political reporter Pia Ranada, who has been banned from the Presidential Palace and covering Duterte’s entourage in retaliation for Rappler’s critical coverage of the President, the latter meant avoiding reporting centred on populist political figures. Instead, her focus was on agenda-setting reporting based on topics. “If it was about climate change or Metro Manila traffic, we would collate the positions of all the candidates for that topic,” Ranada said. Similarly, the Daily Maverick undertook ‘deep dive’ reporting on issues identified as having the most direct impact on citizens and local communities – particularly marginalised townships and forgotten regions. The issues identified for ‘deep dive’ coverage included gender-based violence, housing, education, employment, the youth vote, and sex workers’ rights.

The Quint’s Senior News Editor Jaskirat Singh Bawa noted a substantial increase in the number of fact-checked stories published, even ahead of the election. “We have so many politicians from both the government and the opposition parties indulging in a lot of figures and a lot of data being thrown around, which doesn't always match the actual numbers. Some of these stories [have been] flagged by our readers,” he said. Editor of The Quint’s successful fact-checking vertical WebQoof Malavika Balasubramaniam added that the team was “actively looking for information and not just relying on our readers. We are also trying to identify and understand what is going viral”. Conversely, many of the audience tip-offs come to The Quint via WhatsApp – the Facebook-owned messaging app frequently blamed for sending disinformation viral in India.

Rappler decided to focus election fact-checking on misleading or false stories that ‘spike’ and warrant reporting. It is collaborating with academics and student journalists to identify and fight misinformation during the election period. Fantastical claims have only been fact-checked by Rappler when they have found significant traction, to avoid risking amplifying low-signal falsehoods. At Daily Maverick, Green pointed to the need to give selected academics and professionals with expertise time to review party manifesto content to ensure a considered assessment was able to be provided. “We’re not looking for quick and dirty quotes. It’s about providing meaningful commentary to augment what we’re doing in our own reporting, so that the audience is in a position of power to make informed decisions.”

The social media ‘electorate’

Rappler’s fact-checking capability has involved gathering and analysing data on social media, particularly Facebook to identify networked disinformation and what they call ‘black propaganda’. Rappler managers see this function as a potential public service supporting election monitoring, by providing research aided by network mapping technology to election officials and watchdog groups monitoring propaganda – not only about candidates and parties, but also about the election process. “We can even probably help the Commission on Elections to monitor this in real time,” Managing Editor Glenda Gloria said. “We intend to use those tools to better capture any election violation online, whether that has something to do with advertising, spreading of fake claims, exposing them immediately. Only Rappler has those tools and the staff.” For Rappler’s Investigations Editor Chay Hofliena, analysing key candidates’ social media trajectory to see "[whether] these candidates are working with or are part of a network of disinformation… [is] part of the exploration and investigation.”

At The Quint, there are inbuilt tools, teams and formats aiding election coverage – such as the growing fact-checking vertical WebQoof, and ‘Social Dangal’, a dedicated fact-checking format applied to politicians called ‘neta fact-check’, an explanatory graphical series called Elections ABCD; and videos dedicated to the mechanics of elections, citizen agenda setting via My Vote, and gender-focused election stories sources from diverse communities through Me, The Change.

The Daily Maverick went one step further with their ‘sanity checks’, which fact-checked political manifestos not just in terms of their accuracy, but also in accordance with the reality of the promises being affordable and executable by any South African Government. One of Maverick’s Managing Editors Jillian Green said the response had been positive about ‘lifting the blinkers from readers eyes’. “We’re very conscious of not selling the electorate a false sense of what the parties are offering,” investigative reporter Rebecca Davis, who led the ‘sanity check’ project, said. “We’re constantly asking the question, who benefits from the publication of this story? Are we being used by any particular faction?”

Rappler’s Managing Editor Glenda Gloria said the team would be more discerning of the use of the Facebook Live video tool during elections because of the potential for the exploitation of such opportunities by those peddling misinformation and disinformation – in the absence of mediation. “There's got to be more very selective story selections… You don’t want power to be used to promote certain advocacies that run contrary to yours, which is transparency and accountability. You don’t want to unduly promote people,” she said.

Another challenge for The Quint’s WebQoof fact-checkers and storytellers was based on the different platforms that they use. “The ‘fake news’ is happening on WhatsApp. It's happening on Instagram. There’s these Instagram groups, because it appeals to the younger audience. It definitely happens on Twitter, but that’s not where a lot of the voting class is. We are still wrapping our heads around how to bust this on Instagram and TikTok, but WhatsApp has been the best lesson learned,” Senior News Editor Jaskirat Singh Bawa said.

Mapping propaganda and disinformation

Rappler planned to monitor social media noise and track propaganda networks using new skills learned to map the spread of state-linked disinformation, Managing Editor Glenda Gloria said. The plan was for journalists to track spending in real time by assessing the cost of campaign advertising and events. “The challenge I'm giving to the newsroom is that we can measure it in terms of the billboards, in terms of the campaign paraphernalia. Let's not do this [as a] post-mortem because… we will not have impact then.”

It evolved into a mission to include election-watching of digital propaganda networks - an activist mission that emerged from the failure of the historic gate-keeping role of the press. The Rappler team has targeted a kind of malicious misinformation which they call ‘black propaganda’. Here, the ‘other side’ is smeared to wean away or transfer votes. Banned political reporter Pia Ranada: “It will just be interesting to see how they evolve, like how they morph into viral videos and the strategy behind it. That can be an explainer, right? Is this black propaganda? How do we know it? Can we trace the source of this black propaganda? Who's funding it?”

Ballots and bloodshed

“It’s never been like this before, except in the 1960s when the ANC was resisting apartheid. Bloodshed is a real prospect,” Daily Maverick Senior Investigative Reporter Marianne Thamm said over tea at her kitchen table in Cape Town just a few weeks before South Africa’s national election on May 8th. “This time around I absolutely fear violence – there is a massive pushback going on in the ANC... death squads have been trained. There’s a plan to get rid of [re-elected president] Cyril Ramaphosa. We’re on a knife edge”, she said. The editorial focus, she argued, therefore needed to be on investigative reporting into political plots behind the scenes.

One of the other election coverage strategies adopted at Daily Maverick in recognition of these risks was designed to guard against editorial manipulation by political actors seeking to seed violence and unrest. Open editorial debate is encouraged as a strategy for supporting the outlet’s “strong ethical spine”, as Editor-in-Chief Branko Brkic described as being one of the core characteristics of their journalism. As a result, among election year debates was the need for caution regarding coverage of incendiary fringe political groups. “We had a big debate, for instance, about the amount of airtime we should be giving to fringe political movements... A lot of other media outlets will publish that stuff unthinkingly for clicks – and it does get you clicks. DM staffers and editors do grapple with issues of ethics and representation in a much more thoughtful way than elsewhere,” Rebecca Davis said.

The potential for violence connected to populist politicians using disinformation tactics during the Philippines poll was also concerning Maria Ressa at Rappler. “One, you are being manipulated. Two, people are dying,” said Ressa, who called for a combination of strong editorial values and skilled reporting – combining cutting edge digital network analysis methods and traditional processes – to ensure election coverage quality control.

Drawing on our detailed case study analysis of three digital born news organisations operating in countries where journalism is increasingly under attack, here are our key takeaways for election reporting in an environment of information pollution: