These women-led newsrooms are helping change journalism in the Global South

Members of the newsroom of AzMina, a women-led news organisation in Brazil.

From the COVID-19 pandemic to violence in Ethiopia, Ukraine and Afghanistan, women and girls have been disproportionately affected by recent crises

In a recent report on gender equality in news media, the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) found that only 25% of the subjects and sources in 30,172 news stories studied were women. While this marks a one-point improvement since 2010, the report also exposes persistent challenges. Women are still more likely to report on stories centred around women’s issues, and gender stereotypes are less likely to be challenged in reporting than 15 years ago.

At a time of shifting reproductive rights and ahead of a busy election year worldwide, feminist media can play an existential role. “It is [in feminist media] where you will find the voices best able to call out and counter the rise in anti-democratic impulses and action that is growing all around us,” writes Jennifer Weiss-Wolf in this piece for Ms. Magazine.

Despite many challenges, a cadre of journalists, largely women, advocate for coverage of women’s issues and broader beats like climate, politics and business through a gender or intersectional lens.

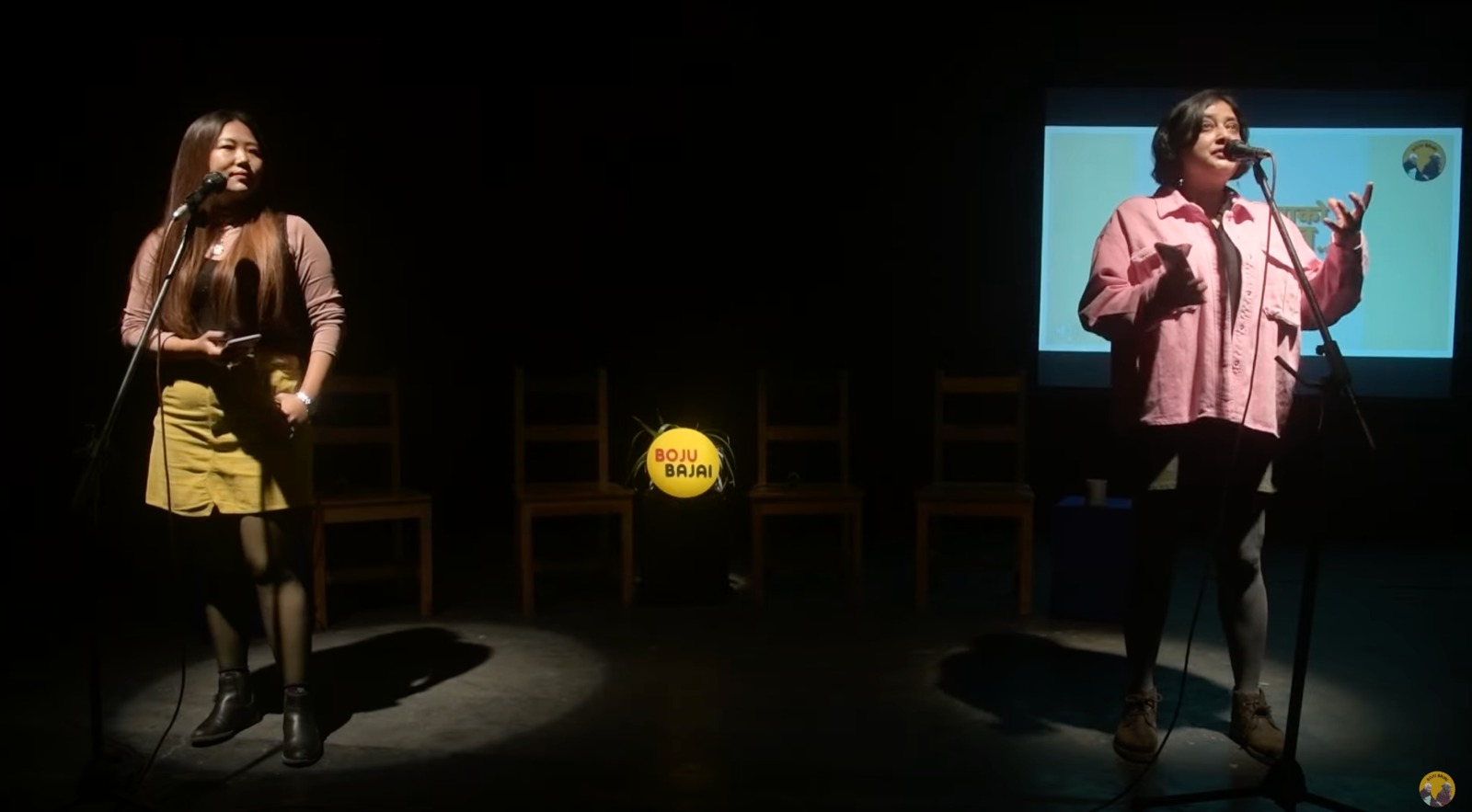

Several independent female-led or feminist media outlets are at the forefront of this trend. In different languages, across different continents and with teams of different sizes, Brazil’s AzMina, Uganda’s HerStory, Nigeria’s BONews Service and Nepal’s Boju Bajai are all part of this movement. I spoke with journalists in these publications to learn more about their work and the challenges they face.

A moment for feminist newsrooms

Carolina Oms and her founders had high-profile journalism jobs in Brazil before launching digital-first, feminist newsroom AzMina in 2015. A reporter with Valor Econômico, one of Brazil’s biggest business newspapers, Oms worked for 12 hours a day and had no time to produce in-depth investigations.

“We were all frustrated with the precarity of journalism, so we decided to do something about it,” says Oms, who’s now AzMina’s institutional and fundraising director.

She defines AzMina as the first feminist media in Brazil and explains it was launched as a response to the failure of mainstream Brazilian media to reflect these changes.

“Newspapers would still call femicide a crime of passion,” she says. “The women on the covers of magazines all looked alike and the discussion about sexuality was centred around men. We want to do investigative work and solutions journalism for women in which they can see themselves.”

For Culton Scovia, who formally launched HerStory in Uganda in January 2022, the platform is a chance to focus her broadcast journalism talents on a feminist themes. But it’s also an opportunity to address the underreporting of women and the gender stereotypes often featured in mainstream media in her home country.

“The newsrooms I have worked in cover women’s issues as though there are no female journalists,” says Scovia. “Stories about women struggle to get media attention.”

Commenting on female-led news outlets in Africa, Sarah Macharia, who directs the GMMP, says shrinking employment opportunities in mainstream media and a sustainability crisis have led to a sprouting of women-led, women-owned micro news outlets.

“These are easily accessible to women for whom the space to continue participating as professionals in mainstream organisations has closed,” she says. “Similar to other women-owned micro enterprises [in other industries], the motivation to set up micro media outlets is economic and perhaps to some extent also driven by a desire to provide a service to the community.

Nepali feminist outlet Boju Bajai started in 2016 as a podcast. Co-founder Bhrikuti Rai has been a journalist for more than 10 years, including for the Nepali Times, The Kathmandu Post and the Los Angeles Times. She met co-founder Itisha Giri, a poet, during rehearsals for The Vagina Monologues in 2016.

Rai and Giri often discussed the state of the news landscape in Nepal and attitudes toward women online. “The news media did not prioritise or have the space for issues that affected us as women,” she says. “It's overwhelmingly men who run the newsrooms in Nepal.”

The idea behind Boju Bajai was to provide an alternative space for an audience of Nepali women “slowly being made visible” online. Rai and Giri’s recorded conversations in Nepali and English about sexual assault, ‘slut shaming’ online and how women are censored. What started as a passion project became a company in 2019.

Stories that matter

AzMina wants the audience to use the stories they produce, whose focus is often on solutions. For example, recent reporting on abortion includes information on what to do if you are seeking an abortion, what rights you have when in hospital and what not to do after the procedure.

Boju Bajai’s episodes now include more narrative, reported stories across all beats, through a feminist lens. This has led to stories on frontline health workers’ mental health, an award-winning two-part podcast on abortion rights and an investigation into what the mass migration of men from Nepal means for social structures and women and girls.

This perspective helps reach more diverse audiences across social classes, geographies and languages than typical mainstream media, says Rai.

Alongside the podcast, Boju Bajai has developed different products to allow it to reach different audiences on different channels. These include Cold Takes, a newsletter rounding up feminist stories from Nepal. Rai says its informal tone creates the space to critique the media’s reporting of women’s issues and gender-based violence.

Blessing Oladunjoye, who founded BONews Service in Nigeria in 2018, says there’s a gender angle to every topic. BONews focuses on issues affecting children and disabled people. Collaborating with advocacy groups on these topics has helped amplify its work. “There are big newsrooms in Nigeria so it’s easier for them to get attention, but working with advocacy groups helps BONews give women a voice,” she says.

A different newsroom culture

The make-up of AzMina’s newsroom is also a response to mainstream media – and starkly different from most newsrooms in Brazil, contends Oms: “We are a mostly black, non-white newsroom.” This better reflects the Brazilian population: according to the 2022 census, released in December 2023, more than half of Brazil’s population identifies now as people of colour.

AzMina’s team is all women – again a contrast to mainstream newsrooms in Brazil, where women filled just 41.8% of available reporting positions in 2018. In radio stations women were outnumbered by men three to one.

“We have policies to take care of the people we work with because they work with difficult issues,” says Oms. “We try to make the environment as inclusive as possible with the money we have available – it’s still not enough.”

Remote working is incentivised to make the workplace more inclusive and extend AzMina’s geographic cover – it has journalists working in more than 20 of Brazil’s 26 states and partners with media organisations in the north of the country and in the Amazon region, where it does not yet have team members.

Rai says she wants Boju Bajai to differ culturally from its mainstream counterparts too. As a four-person team, it’s open to collaborations to extend and amplify the scope of its journalism. As journalists in Nepal’s newsrooms fight for better pay, despite Boju Bajai’s size, Rai pledges to always pay those it works with fairly.

A feminist audience?

With a range of products and the difficulty of accessing podcast metrics, Boju Bajai views itself first as an online community for young Nepalese women and girls and measures its impact in these terms. It had an almost full house for a live podcast recording, for example, with attendees paying what they feel despite a culture of not paying for such events in Nepal, says Rai.

AzMina’s web stories also find a male audience: according to Google Analytics, one third of its users in November were men. Amongst its social media audience, however, 80% are women and “very young.” The newsroom’s audience research suggests that for many of its social media fans, AzMina was their first encounter with feminism.

“They begin at 15 years old,” says Oms, saying this group of “AzMina lovers” are more likely to share, engage and donate. The team has produced two documentaries alongside its digital journalism and shown these in public schools. After the last viewing, female students said they planned to found a student feminist organisation.

Here comes the backlash

Response to AzMina’s work has not always been positive. In 2019, Brazil’s then minister for women, family, and human rights filed a complaint with the public prosecutor’s office following an article on safe methods for obtaining abortions. Team members’ photos and home addresses were doxxed and the website was taken offline. The newsroom has strong digital security protocols after suffering numerous cyberattacks, including DDoS attacks.

Opponents have previously branded AzMina’s work as activism journalism to undermine its credibility. The team comes together fortnightly to discuss their work and any safety concerns or issues raised by the topics reported.

Boju Bajai’s Rai was initially surprised not to see more public support from men who privately encouraged the project, but she believes this is a reflection of Nepali society’s general attitude to feminism.

The platform has been criticised for receiving grants and foreign funding to fund special podcast series and its founders have been labelled as “dollarwadi” feminists – a term frequently used in parts of Asia, including Nepal, to suggest greediness and used to dismiss the work of feminist organisations, including Boju Bajai.

“Over the years we have made sure that we don't let such criticism get to us, by playing on this narrative to create more tongue-in-cheek content about people who use such terms,” says Rai.

Ensuring the safety of reporters and sources, especially for journalists who don’t operate from Kathmandu, is critically important, says Rai, who explains that any abuse aimed at Boju Bajai has so far been online rather than physical.

Rai uses her personal social media accounts less and less to avoid trolling and other online abuse. But she acknowledges that social media has ultimately been crucial for the platform’s growth.

When asked, Scovia and Oladunjoye say they have not personally experienced threats or abuse either for being female journalists or for reporting on stories through a gender lens. Oladunjoye has faced resistance from Nigerian government agencies, including accusations of malice and “not portraying the state in the right perspective”.

While there are safety concerns for female journalists reporting from certain places, she thinks that BONews’ team can build trust more easily with communities of disabled women, for example, than mainstream media.

A central issue in Uganda, says Scovia, is the lack of space given to coverage of women’s issues. “It is not that women do not want to comment on these issues or that we do not have female experts in this kind of field,” she says. “You [newsroom editors] do not approach them, you do not reach out to them.”

How to fund feminist newsrooms

Before launch, AzMina’s founders imagined the main revenue streams would be advertising from brands and donations, but these revenues proved hard to attract. Instead, AzMina was asked to deliver internal workshops and talks for organisations.

This is still something the team does, as it allows them to connect with a wide range of women, including those who don’t consider themselves feminists, as well as like-minded companies. Such activity accounts for less than 10% of its income.

International foundation funding now makes up approximately 70% of AzMina’s revenue, but this wasn’t always the case, says Oms: “We don’t come from the philanthropy ecosystem. We didn't know how to get funding.”

Crowdfunding from readers helped show potential funders that AzMina has support from its audience even though the content is available for free. Reader donations are still 10-20% of revenue. “It’s not a huge number but it’s very important,” Oms says. “We can use donations to connect with people; it’s not all about the money.”

Boju Bajai has a similarly diverse revenue portfolio. Initial funding from Open Society Foundations helped get the idea started and grants are still important, but the organisation is aiming to generate at least a quarter of its revenue from other sources – many of which weren’t available when it launched during the pandemic.

For example, Boju Bajai trains other organisations looking to produce podcasts. The team has tried to source in-podcast advertising, but the return on investment wasn’t there. Partnerships with like-minded organisations work better. For example, it has run social media campaigns with UN Nepal and produced episodes with Urgent Action Fund, a feminist activism fund.

“We've realised that perhaps Boju Bajai is not supposed to be this massive conglomerate. That's not what we are aiming for,” says Rai. “We just want to be able to serve our audience, no matter how small.”

The long-term sustainability risks for these newsrooms are high, says the GMMP’s Macharia, adding that few women-owned media organisations in Africa command wide audiences: “The outlets will remain very niche, serving tiny audiences if they are eventually unable to grow, a consequence of shoestring budgets and capacity limitations.”

Scovia wants HerStory to become more consistent, producing stories more regularly and launching more investigations. To date, however, the site has been personally financed by Scovia and her team. A new partnership for the site starting in November is a test of a different revenue model with three stories per month funded.

For BONews funding is a challenge too. Oladunjoye initially used her income from other journalism work to fund the newsroom. Story grants from the Solutions Journalism Network, for example, have enabled some specific reporting and freed up resources for operational needs, but she is applying for additional funding not tied to individual stories and thinking about establishing an NGO arm to incorporate more advocacy work.

Changing the landscape

While these newsrooms work towards security and sustainability, the impact of their feminist focus and values is already being felt. In Brazil, says Oms, things have changed for the better: another major print title calls itself feminist now and gender violence has risen on the public discourse agenda.

“A lot of magazines and newspapers, not only those that are women-led or for women, have begun to do stories that could be considered feminist,” she says, though reproductive rights and sexuality are still seen as potentially alienating to sections of mainstream media’s audience.

Fortunately for women in Brazil and around the world, that’s where newsrooms like AzMina (as well as India’s Khabar Lahariya, Somalia’s Bilan Media and exiled Afghanistani newsroom Zan Times) step in. “We say where we stem from and we are not going to say ‘Amen’ to injustice,” Oms says.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time