How an old newspaper in Hiroshima is keeping the memory of survivors alive

Kunihiko Sakuma, an atomic bomb survivor, poses for a photograph in front of the Cenotaph for the Victims of the Atomic Bomb in Hiroshima. REUTERS/Issei Kato

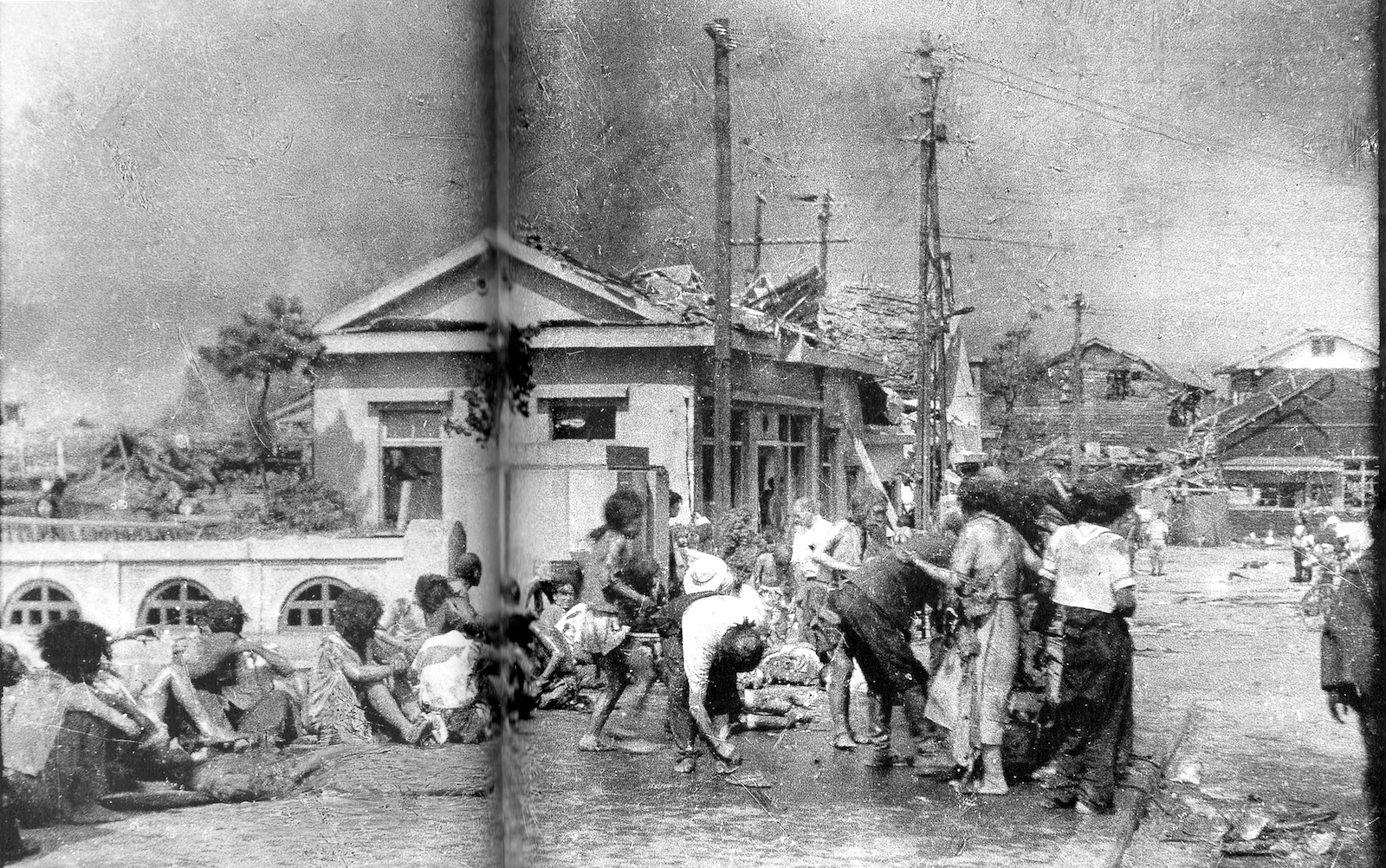

On 6 August 1945, an atomic bomb exploded above Hiroshima, about 900 meters from the offices of Chugoku Shimbun, one of Japan’s leading newspapers. By the end of that year, more than 100,000 were killed due to the blast, heat rays and radiation, including 113 employees of the newspaper.

The newspaper’s offices were completely destroyed, including the two rotary presses. One-third of the people in the building were killed and the surviving employees were injured. Many lost family members too.

From the very next day, however, employees of Chugoku Shimbun took on the responsibility of documenting the first nuclear attack in human history.

There are many photos of the bomb’s mushroom cloud taken from a distance that day, but very few that capture the human cost of the bombs from up close. The five images captured by staff photographer Yoshito Matsushige depict what happened to human beings under the atomic cloud.

“Of course, they won’t tell everything about the horror of the bombing, but I still feel I had done well to get even a few pictures under such extreme circumstances. Without those photos, nothing would tell what really happened,” he said to the International Review of Red Cross in an account years later.

The employees were not insulated from the impacts of the bomb. Yasuo Yamamoto, who was manager of the paper’s stenographic department, wrote an account of how those few days in August had impacted him: “After 20 days my hair began to fall out in the places where I had been burned … But I couldn’t take a day off from our preparations to put out the paper, so I continued to make that long-distance round trip by bicycle with my white bandages on. Some of those who had been lucky enough to escape harm began to come back to work and then got leukaemia and died. I was depressed and wondered if we’d really be able to put out the paper there.”

With the help of other newspapers, Chugoku Shimbun remarkably restarted publishing on 9 August, only three days after the bomb was dropped. It was printed by other newspaper companies until 3 September.

On 17 September 1945, its publication came to a halt again when a massive typhoon hit Japan. But the employees of the newspaper soldiered on, literally in the eye of the storm.

In the 80th year of Hiroshima's bombing, few survivors are left to tell the story first hand and the world is growing more volatile, with President Trump calling for a new missile defence system and a changing global order. In this volatile environment, the journalists of Chugoku Shimbun feel the need to warn the world of the dangers of nuclear weapons urgently. So they have started reporting an 80-year-old story with the urgency reserved for breaking news.

The urgency of history

“Since then, we have been thinking about peace obsessively,” said Yumi Kanazaki, director of the Hiroshima Peace Media Center, who has worked in the organisation for 30 years now. “One of the ways we hope to foreground peace is by relentlessly documenting human tragedy in the aftermath of the a-bomb,” she added.

The Hiroshima Peace Media Center, which is part of the Chugoku Shimbun newsroom, does peace-related reporting in multiple languages and advocates for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the advancement of peace in the world. Established in 2008, the center’s website contains more than 23,000 articles, which cover not only the damage caused by the atomic bombing and the current state of nuclear weapons in the world, but also issues involving nuclear energy, including the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant and the suffering that Japan inflicted on the people of other nations in the past.

Today, the office is in downtown Hiroshima in a plain white building unadorned by sign boards. The newspaper sells around 480,000 copies with Kanazaki saying that sports, city news and lifestyle news are among the most-read pages. Most of their revenue comes from subscriptions and advertising.

Numerous photographs connected to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima are also featured on this dedicated website, as well as articles contributed by experts on nuclear issues from around the world. The website has millions of visitors from 200 countries and territories. Kanazaki estimates that nearly 10% of these visits are from outside Japan.

Maintaining the memory alive

Another area of focus for the Chugoku Shimbun involves handing down the experiences of the atomic bombing to younger generations.

The 400-strong newsroom comes together to plan stories that should be published in August every year.

Last August, they started a series simply called Documenting Hiroshima. It is an ongoing series rigorously researched based on records and testimonies of citizens of that time. “We have tried to get to the story from all angles possible,” said senior writer Kyosuke Mizukawa, who has anchored the project. They have published one story almost every day since August 2024.

The newspaper is now working on this 80-year-old story with a true sense of urgency. “Most atomic bomb survivors are in their 80s, and there will soon come a time none of them will be around,” said senior staff writer Michiko Tanaka. “Many don’t have clear memories already.”

Reaching out to survivors

Three days after the US dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, they dropped another nuclear bomb on Nagasaki. Therefore many survivors of these bombs – called hibakushas – are spread across both the cities, and others have moved to other cities in Japan or overseas.

Earlier this year, rival newspapers Chugoku Shimbun, Nagasaki Shimbun and Asahi Shimbun came together to draft a questionnaire to send to as many of the survivors as possible. “We do realise that they are tired of telling their stories over and over for the past 80 years,” said Tanaka.

They distributed the questionnaire to 11,000 survivors in the 47 prefectures of Japan. About 3,564 responded, including 916 people living in Hiroshima.

Although such questionnaires have been distributed to hibakushas in the past, this one was different, asking questions about the survivor’s feelings regarding nuclear weapons.

Having a nuclear bomb

Japan is covered under the US nuclear umbrella. This means if any country were to attack Japan, the US has taken the responsibility to defend Japan. However, given the global uncertainties on the economy and Donald Trump’s second term, many in Japan are nervous about their security.

Proximity to China and South Korea has put Japanese leadership on edge too.

“You can’t really take the US presence for granted,” said Matsukawa, a member of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) influential national security policy council. “Trump is so unpredictable, which is his strength maybe, but we have to always think about Plan B. Plan B is maybe go independent, and then go nukes.”

This is in direct conflict with the way the hibakushas feel. Around 80% of the hibakushas who responded to the questionnaire said that Japan should join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a legally binding international agreement that aims for the total elimination of nuclear weapons.

Constantly working with stories about their city going up in nuclear flames takes a toll on the mental health of the staff, Tanaka admitted. “I cry with the survivors every time I interview them,” she said. But, she said her and her colleagues lend their shoulders all the time. “Unless we support each other, we cannot get through a doomsday story like this for eight decades.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time