How a newsroom of teens is fact-checking news for their generation in Brazil

Mediawise's TikTok account.

Every year since 2018, a new cohort of reporters is welcomed to MediaWise’s virtual fact-checking newsroom. They scan social media looking for pitches, bring story ideas to their editors, and then prepare a piece for publication by scripting and shooting their own videos. What makes this fact-checking newsroom different from others is that all the reporters are mostly 13 through 21 years old.

MediaWise is a nonprofit initiative of the Poynter Institute that fights disinformation by educating teens about media literacy. Its Teen Fact-Checking Newsroom (TFCN) launched in 2018. “What makes TFCN a little bit different from other regular fact-checking organisations is that not only are they fact checking, but they're also teaching a media literacy skill to their peers,” says youth programming manager Kathleen Tobin.

The fact-checkers are paid like real reporters and produce videos on MediaWise’s TikTok and YouTube channels. Fact-checking claims range from drug dealers targeting kids on Halloween through candy (they are not) to comparing two pictures of the Arctic 100 years apart to see if they are legit (they are).

The purpose of the TFCN is to help young people sort out what is fact from fiction. Tobin, who has a background as a journalist and journalism educator, serves as the newsroom’s editor and teaches participants how to fact-check. “Not only do they pitch me a possible claim they want to fact-check and how they're going to fact check it, but also what media literacy skill they might use,” she says.

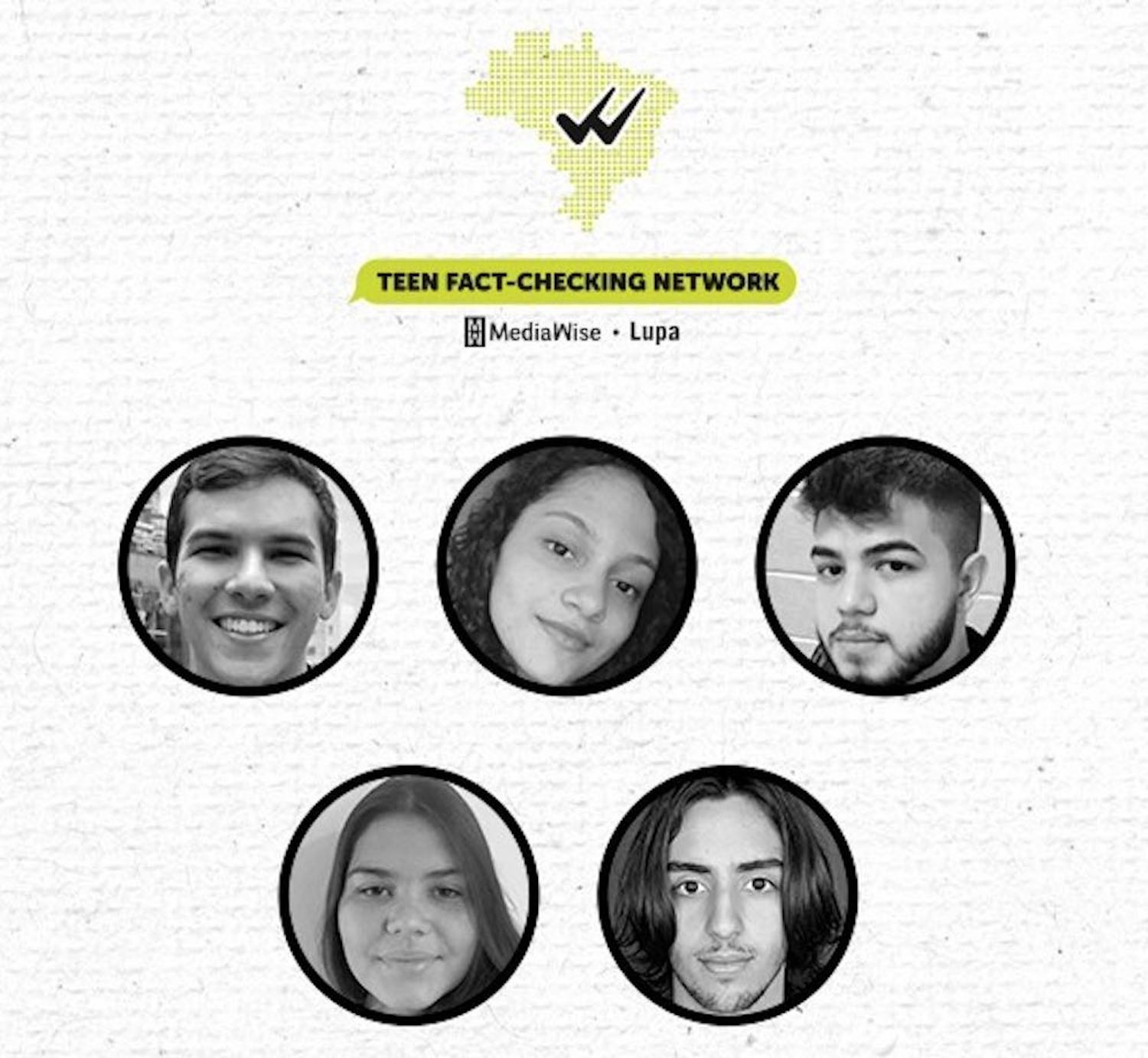

The project is now going international. Partnering with Agência Lupa in Brazil and Deutsche Presse-Agentur (DPA) in Germany, the teen fact-checking newsroom is expanding beyond the United States. I spoke to some of the young people behind Brazil’s operation about building a newsroom for Gen Z by Gen Z.

Zooming in on Brazil

The media landscape in Brazil deteriorated after the election of former President Jair Bolsonaro, who regularly attacked journalists publicly. In fact, most of the young people I spoke with said they were emboldened to join the project after seeing the increasing amount of misinformation being spread in Brazil during Bolsonaro’s presidency.

“During the election and the pandemic, there was so much disinformation,” says Camila Reis, a 17-year-old high-school student from Rondonia, in the North West of Brazil. “I would get to school and there was this person saying this, and that person saying that and I would be like, ‘wow, what's going on? How does this disinformation get to you? What makes you share this? And why do you believe in this? Why did you never stop to research and see if this is true?’”

One of the most prevalent conspiracies at the time, she says, revolved around communism. Many conspiracy theories in Brazil are attached to anti-communist sentiments, and these took a new spin with COVID-19. Some even said that the pandemic was part of a communist plan for world domination.

Throughout the 2022 presidential campaign, Brazilian voters were bombarded by online misinformation, particularly on social media platforms. According to one of the reports of our Trust in News Project, most Brazilians say misinformation is a problem on platforms like Google, Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube. Trust in news has fallen 16 points in Brazil since Bolsonaro’s election in 2018. Although correlations between age and trust are not especially big in Brazil, under 35s are the lowest-trusting age groups, according to our Digital News Report 2022, with only a third of both 18–24s and 25–34s saying they trust most news most of the time.

The teen fact-checkers in the project are avid news consumers and admit that the main way they get their news is through the Internet and social media networks, particularly Instagram and Twitter.

“Teenagers like fast things and don't really look at what they're sharing,” says Linda Oliveira, a 19-year-old student from the outskirts of São Paulo. “This is a real problem: that we just share and don’t pay attention to.”

How to engage with Gen Z

The participants say that the best way to reach their age group is to meet them where they are, which is why they were intrigued by the project in the first place. “Young people and teenagers in general have great access to the Internet,” says Reis. “The best way to disseminate facts is precisely within social networks.”

Alessandro Fernandes, a 21-year-old journalism student from Fortaleza, joined this newsroom to understand what journalism looked like in the country after so many years under attack. “In the past four years, we’ve had bad experiences with fake news and disinformation,” Fernandes says.

Bolsonaro’s government was notorious for its antagonism of journalists. The attacks ranged from offences and threats to journalists to boycotting campaigns against the main Brazilian TV channels and publications.

Bolsonaro has also spread disinformation himself. According to a federal police report, the former President had a "direct and relevant" role in spreading disinformation about the country's electoral process during live-streams on social media. Additionally, a group of Bolsonaro's allies allegedly coordinated a disinformation campaign ahead of the 2022 election targeting his political rivals, according to a public extract from a federal police probe.

To fight misinformation among their peers, these young fact-checkers are tasked with debunking fake news online. “They are supposed to create videos,” says Carol Macário, a non-teenage reporter at Lupa who is helping train the teens. “They’re supposed to debunk some stories and some claims and we are going to help them fact-check those claims.”

How teens are trained

Dominique Gogolesky, educational analyst at Lupa, says that the training process is a collaboration between the young people and the reporters at Lupa, who have been running a training programme for journalists at large since 2017. “[The programme] was really focused on fact-checking techniques and methodology,” says Gogolesky. “In 2021 we changed it to focus on media literacy so we are using our experience to build with this team the methodology of fact-checking but also on media literacy.”

While training the young people was somewhat based on the techniques of that programme, the process is very much collaborative, with the team meeting once a week online. The syllabus includes theoretical classes, practical exercises, and even lectures with other checkers from India and Germany. The initiative runs for seven months, starting in March and ending in September.

Similarly to the teens in the US, these Brazilian teenagers will be pitching, fact-checking, scripting, recording, and editing themselves, and they are already planning what their first projects will be about. Once they’ve finished them, they will be published in the Agência Lupa pages from mid-June.

Tiago Cortes, a 19-year-old student in the Northern state of Roraima, says he wants to focus on debunking misinformation about his state as he thinks it’s the only one being covered negatively by the national media.

“[Roraima] is the state with the highest percentage of Indigenous people in the country,” says Cortes. “I want to bring information about Indigenous culture and about the Amazon.”

Others just want to speak truth to power and target issues that affect their communities and their generation. David Rodrigues, a 20-year-old law student from Pará, says that disinformation is very present in his region and also among his peers. “In my region there is a very strong presence of authoritarianism and these people have a very strong investment in disinformation,” says Rodrigues. “In my city people are in need of information. There can be a collective hysteria by fake news and by the lack of instruction in identifying whether information is false or not.”

Rodrigues recounts an incident that happened at his college where students began debating the existence of a ‘non-binary bathroom’ in his province. “For the first time I bursted,” says Rodrigues “I said that we were 20 minutes discussing something that didn't exist – there is no ‘non-binary bathroom’ in Marabá.”

He said this debate of something that didn’t exist made him join the Lupa project to help people tell what's real from what is not. “It's about trying to be part of this active militancy in the fight against disinformation,” says Rodrigues.

Social media as a double-edged sword

Fact-checkers see the Internet and social media as both conductors of disinformation and tools to fight disinformation, particularly for this age group. TikTok has emerged as a fast-growing outlet for news and information among young people. Research from the Reuters Institute reveals that almost half of 18-24-year-olds use TikTok for any purpose and one-in-five use the app for news. Some of the fastest growth has taken place in Latin American countries and particularly in Brazil, where this social network has been widely adopted.

For some of the fact-checkers, the reliance on social media for news can be problematic. “I think it is dangerous to get informed this way because it is content created to generate engagement and not with the intention to inform,” says Cortes. “Journalism often doesn’t gather visibility on the platform.”

Many of the participants in this initiative see journalism as an essential agent in maintaining the democratic institutions of Brazil. In fact, some of them are already studying journalism or thinking of going into journalism themselves to improve the state of the profession in their country. “As a student of Journalism in Brazil, I believe that we have an important instrument to defend democracy and represent the interests of people, specially the communities living in favelas, indigenous villages, rural zones and ribeirinhas areas,” says Fernandes.

For others, this project is an opportunity to contribute to the journalistic landscape of their country, but it also gives them the opportunity to tell stories that are important to them. “The best part of doing journalism is social communication,” says Cortes. “We can give visibility to social minorities, tell inspiring stories, and by exposing a complaint we can pressure the government to do something.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time