Japanese public broadcaster NHK has monitored misinformation for over a decade. Here’s what they’ve learnt

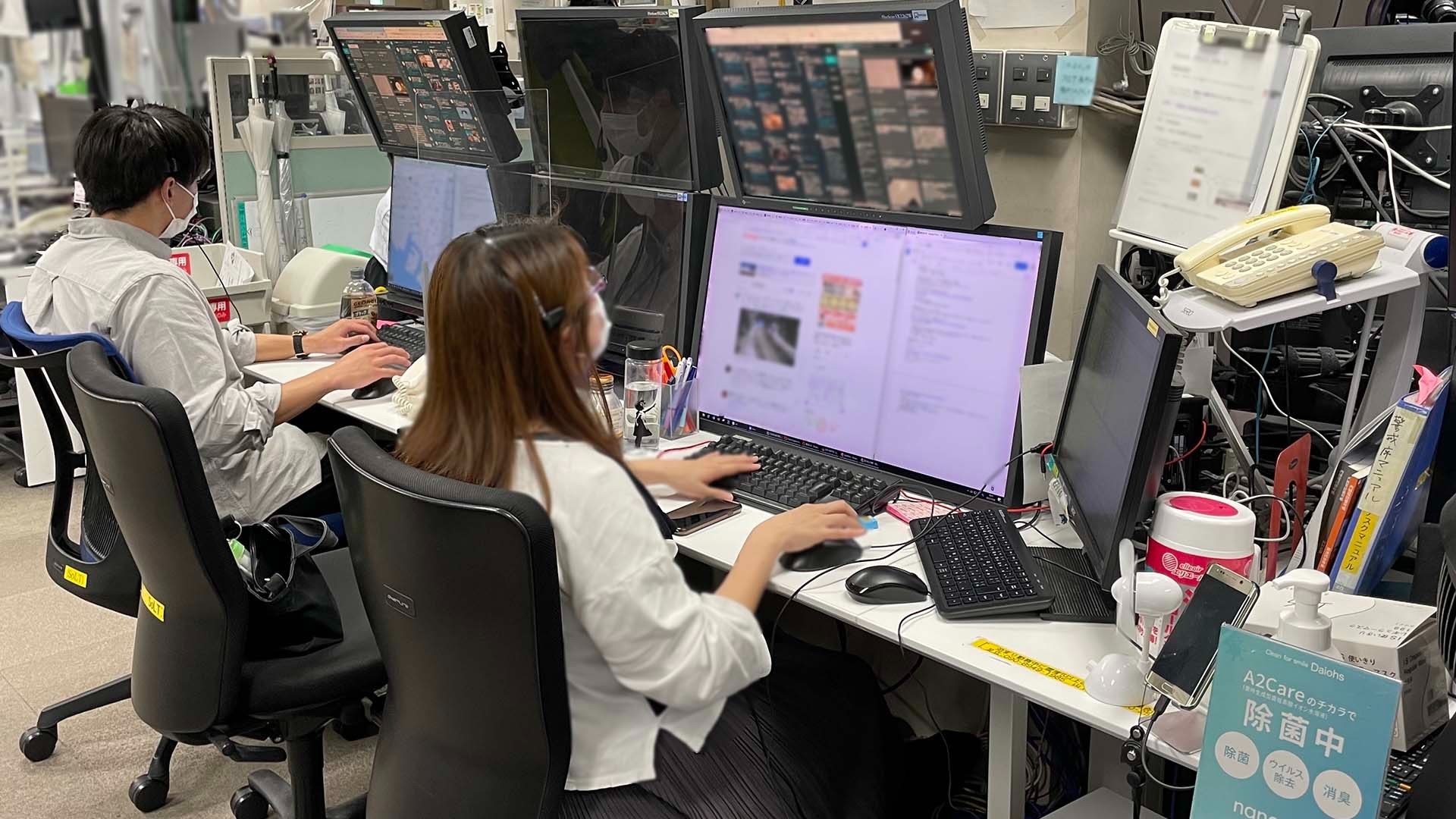

Propelled by increasing social media use, managers at Japan’s public broadcaster NHK felt the need to monitor social media. That’s why they launched the Social Listening Team (SoLT), a small newsroom that closely monitors Japan’s X and Facebook every single day 24/7. It has been operating since 2013.

Given the increase in misinformation across social media channels and the public's reliance on social media for news consumption, they felt they needed to put more resources on fact-checking news items on social media. Every week they run at least 2-3 pieces debunking fake news and misinformation, and explainers on how to deal with misleading content on social media.

The Social Listening Team has been particularly effective any time that news about natural disasters or street crimes breaks on social media.

In the aftermath of the Noto earthquake in Japan in 2024, for example, posts on social media falsely claimed the earthquake was man-made. “We saw 250,000 posts on the artificial earthquake hypothesis by the end of the second day,” said Kaori Iida, then-Director of the Digital News Division at NHK.

The Social Listening Team was originally launched to make effective use of social media in NHK’s broadcasting. But monitoring and fighting such a deluge of misleading information on social media is only a part of the team’s role. Housed in NHK’s head office in Shibuya city in Tokyo, the team includes journalism students and monitors social media in three shifts checking news in Japanese and other languages.

NHK’s Junya Yabuuchi works closely with the Social Listening Team to tackle misinformation. He has covered science, technology, and healthcare for nearly 20 years. Previously, he was based in New York and reported on issues like NASA, cancer research, and the #MeToo movement. He also reported on atomic bomb survivors when he was in Nagasaki. During the pandemic, he was one of the main news editors who covered COVID-19 and its effects on healthcare and society.

I recently spoke to Yabuuchi to learn more about the Social Listening Team, why it is important for Japan’s public broadcaster, and how it could be replicated elsewhere.

Q. When did you launch the project?

A. The starting point was the great earthquake and Fukushima nuclear power plant accident in 2011. At the time, Twitter and other platforms were becoming popular in Japan. One of our news desk editors who was overseeing social media posts related to the earthquake came up with the idea. It was not an experimental project. We quickly gathered around a dozen people, including reporters and students working part-time in the news desk. We were very encouraged by the response.

Q. Why did you feel the need to launch this project?

A. At the time, we did not have the know-how to even check the truthfulness of information that was shared on Twitter. At the same time, there was a lot of misinformation about the damages and about the Fukushima accident. These factors made us feel the need to monitor the information coming out on social media.

As NHK aims to provide our audience with accurate and reliable information, we make sure that only verified information goes out on our traditional media like TV and radio, and also on our official social media channels.

Q. How has the situation changed since the time you started? Do you still monitor the same platforms? Do you continue to work in the same way?

A. In response to the evolving landscape of social media, we have adapted our monitoring strategies accordingly. While we scrutinise various platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky and Threads, our primary focus remains on X (formerly Twitter) due to its high usage rate in Japan and the rapid dissemination of information. This is particularly crucial for swiftly detecting incidents when they occur.

Having said that, X is a significant source of dis- and misinformation as well, and this trend has accelerated since its acquisition by Elon Musk. So we do monitor other social networks as needed, but X remains to be one of our major platforms and we monitor it 24/7.

Q. Why did you decide to get students involved in the project?

A. At the beginning, university students were the only possible option, since we needed so much manpower to monitor social media 24/7. We called on students who had already been assigned to work as NHK reporters, and also on students who were working part-time at NHK. Students were very helpful in suggesting words to search for on Twitter, and their participation really made the monitoring process effective. The students are paid for the work they do at NHK.

Q. Can you give an example of a piece of misleading content that students marked as suspicious while monitoring social media?

A. During the latest US election, a student observed an “image of a poll showing Donald Trump with a large margin over Kamala Harris in the US presidential election” going viral. Upon investigation, they found that it was a screenshot from a website that allows users to freely change the colours on a map of the United States. So we immediately notified everyone in our newsroom that this was not real.

Another example was related to the COVID-19 vaccine. There was false information saying that “the virus would spread from someone that had that vaccine injection”. By monitoring social media, we found that shops and beauty parlours were rejecting people who had been administered the injection. We investigated this claim and aired a news report with verified information and an explainer on what was going on.

Q. Do you factcheck Japanese politicians or is that off limits due to impartiality rules?

A. The need for fact-checking statements made by politicians often becomes prominent during election campaigns, and this is a challenging aspect for us due to the necessity of maintaining impartiality as a public broadcaster. However, in recent years, there has been a noticeable trend of unsubstantiated information spreading on social media, particularly during elections. As the election of the House of Representatives approaches this summer, we are now deliberating on how best to address this issue.

Q. What would be your advice to other news organisations willing to replicate this approach?

A. You need people with news judgement who can post on the kind of information that’s flying around in social media, but also IT-savvy people who closely observe what is happening. Our team is funded by NHK’s budget. The cost will depend on how much manpower is required. Operating 24/7 costs significant amounts of money. But you can start a team like this with just a few staff members.

Q. We’ve seen lots of climate mis- and disinformation trending lately. How has your team monitored this?

A. Japan is prone to natural disasters and every year they become more extreme. For this reason, fewer people are sceptical about climate change than in countries like the US. In Japan, false information about the damage caused by disasters seems to be more common than information about the causes of climate change.

During a typhoon in August, some people falsely claimed that“a river near Tokyo overflowed” by using images of past disasters or overseas floods. We caught this spreading on social media, reported it on the news, and urged people to be careful.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time