People are turning away from the news. Here’s why it may be happening

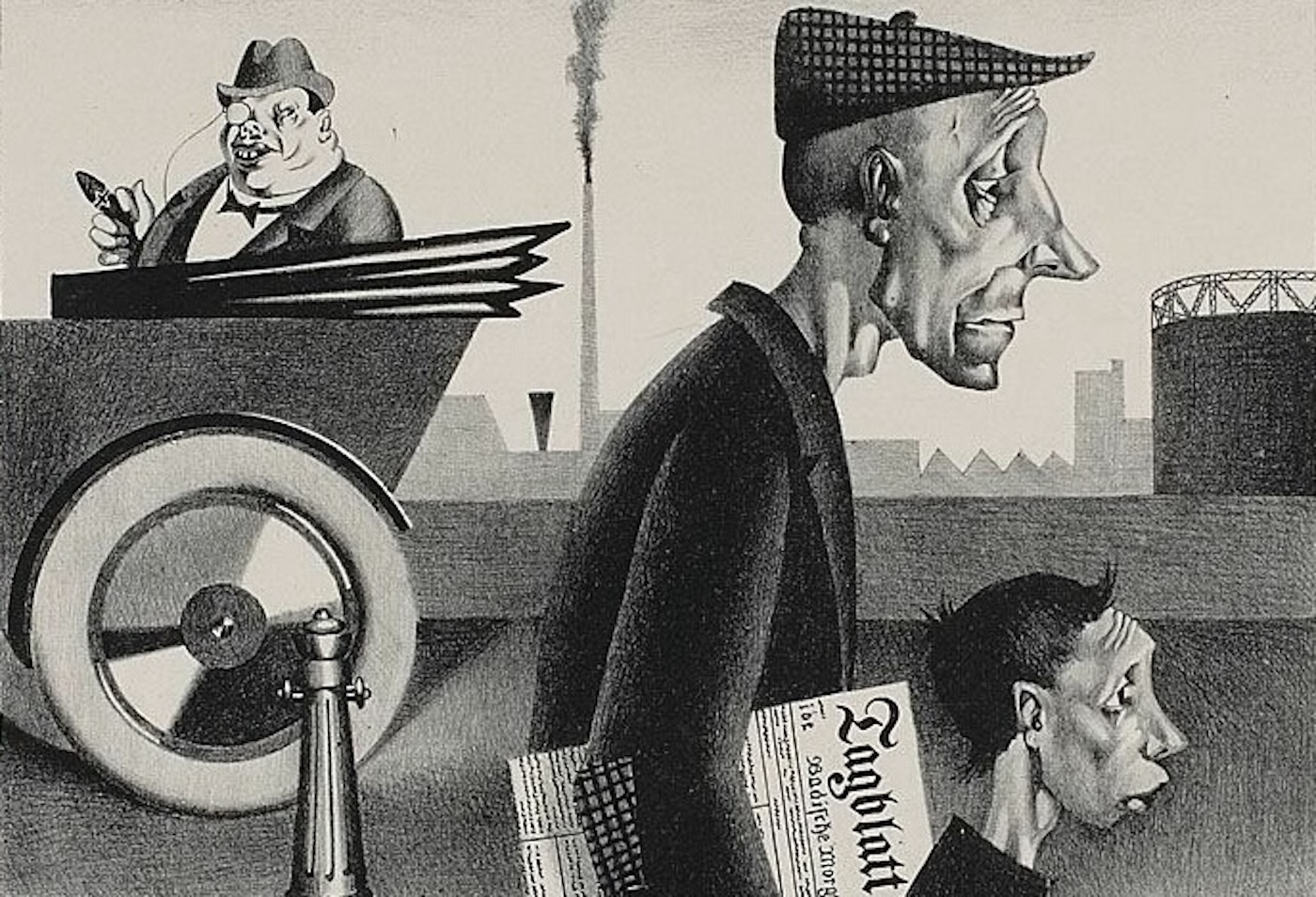

Newspaper Carriers (Work Disgraces) (1921) by Georg Scholz. Art Institute of Chicago.

Our research shows an important trend in the world of digital news: across countries, we are seeing stagnation or decline in online news engagement. People are turning away from the news – and this has a number of implications.

In this article, we explore this apparent disengagement from online news and examine what might be going on. This piece is based on data from our annual Digital News Report survey. Across a group of 17 countries we have been tracking since 2015 1, we trace falling interest in news and rising news avoidance. The trends are worse among younger people and those without a university degree, compounding already-existing information inequalities – “the uneven distribution of news use across the population” (Fletcher et al., 2020) which comes as a result of various factors we will explain in this piece.

Drawing attention to this trend is important because this declining news engagement may have negative implications for democratic participation and for combating misinformation, among other things. The news media provide people with information they may need in their daily lives, yet many are turning away from them.

The decline in online news engagement

Every year we ask respondents in our Digital News Report survey to tell us where they got their news in the last week. The charts below show trends in online news consumption between 2015 and 2024, broken down by age and education (degree or no degree). These are the proportions of people who say they got news online via any means, whether that’s directly going to a news website or seeing news on social media.

At the outset, it must be noted that online news consumption in general has been flat or declining in many countries. However, weekly use of online news has fallen at sharper rates among younger people and those without a university degree. Between 2015 and 2024, the proportion of 18-24s using online news weekly fell by -13 percentage points, compared to just -5 points among those in the 55+ age bracket.

While a higher proportion of younger people have consistently used online news over the years, with many older people still preferring to consume news in print or on television, this trend is shifting: we can now see that the proportion of 18-24s consuming news online sits below the proportion of 25-34s and 35-44s consuming news online.

This drop in online news engagement is not made up by offline news use: In the UK, for instance, only 11% of 18-24s reported using print news in 2024, and only 32% reported using TV news.

When it comes to education, we see similar disparities. The fall in online news usage between 2015 and 2024 has been -7 points among those without a university degree, compared to no meaningful change (-1 point) among those with a degree.

Keep in mind, however, that these are aggregate figures. Not all countries show the same trends, with Nordic markets, for instance, tending to stave off larger declines. The proportion of people in Finland consuming news online has only dropped -2 points since 2015 (from 90% to 88%). But the fact we see declines even in aggregate data that includes these countries tells us something about the size of some declines in markets like Brazil, where the proportion of people consuming news online has dropped -17 points (from 91% in 2015 to 74% in 2024).

The aggregate fall in online news consumption across a combined 17 countries and in only a ten-year timeframe raises the inevitable question.

What explains these declines?

There are many factors which may go into explaining the decline in online news engagement overall (and among some groups more than others). Explanations are often intertwined, operating in tandem. This makes explaining audience behaviour a complicated endeavour, which means the following does not purport to be an exhaustive accounting of possible explanations. But these are likely contributors.

1. A sharp fall in news interest

One of the strongest predictors of news consumption we tend to find in our research is interest in news. Naturally, you need to be interested in something in order to spend your time on it, whether that is playing video games, reading books, or consuming news. The charts below show trends in the proportion of people in each group with high interest in news.

As it is clear, there has been a decline in interest among all groups over time. The decline is steeper among those in the youngest age group and those without a university degree. Between 2015 and 2024, interest in news fell 22 points among 18-24s and 19 points among those without a degree. This may be contributing to reported declines in online news use.

When it comes to explaining why interest in news itself has fallen so steeply, and especially among certain groups, there are, again, many possible explanations.

One may be in the lure of other more appealing content online. A study by Markus Prior (2005), for example, pointed out how an increased availability of entertainment content can lead people to opt out of news consumption and instead choose that entertainment content instead. Prior noted that this has negative implications for democratic participation and political knowledge. This ‘relative entertainment preference’ may be stronger among younger people, especially because they have grown up in a world of abundant entertainment content online.

The way that social media sites or apps in particular operate is also a likely contributor to declining news interest and engagement. Social media algorithms are optimised for engagement, with the goal of keeping people on the platform as long as possible. This has seen social media companies prioritising things like entertaining short-form video and de-prioritising news. Facebook, in particular, has turned away from news and fact-checking following years of grief from all sides of the political spectrum.

Political news caused headaches for them, so they turned away. This is also a very likely contributor to declining interest among audiences: the deluge of political news has put people off, as we’ll see in the next section.

At the same time, however, if news is present on social media platforms, the way that they are optimised for engagement can mean that the most enraging, upsetting, or generally polarising content rises to the top (Bellovary et al., 2021). The negative comments underneath these news stories also add another layer, exposing people to media criticism and contributing to declining trust and interest in news (Dobber and Hameleers, 2024; Dutceac Segesten et al., 2022).

Another possible reason for these trends among younger people and those without degrees may be a lack of positive representation. A Reuters Institute report on trust in the news media (Ross Arguedas et al., 2023) found that working class people in the UK, for instance, often felt misrepresented and mistreated by the news media, which accounted for some of their low trust and disengagement.

Participants in the research spoke of not receiving attention from the news media and, if they did receive coverage, the reporting being negative, casting them as villains. If working class people feel that they are being portrayed this way, it may be no surprise if their interest in news declines and they engage less with news.

The same goes for younger people, especially young women, who perceive the news media as often representing them unfairly (Fletcher, 2021). News is not always made to feel for them. Higher interest in news among other groups who are catered to (i.e., wealthier, older, white men) sees the information rich getting richer, while the information poor get poorer.

At the same time, news may not be catering to the needs of different people. Our Digital News Report 2022 found that younger people were more likely than older people to avoid the news because they found news difficult to follow or understand, again highlighting how the news can be made to seem ‘not for me’ (Newman et al., 2022). As for education, in the US, the ‘diploma divide’ between people with and without college degrees is increasingly shaping people’s attitudes and behaviors (Zingher, 2022).

These factors, however, do not necessarily cover the full range of reasons behind the decline in news interest and online news engagement. There are likely many reasons which remain unexplored, requiring further academic research.

2. Tuning out the news: disengagement, avoidance, and fatigue

In recent years, we have noticed a trend in our data where an increasing number of people across countries say they don’t consume news – either offline or online. The charts below show the proportion of people in different groups who say they don’t consume news in print, via broadcast media, or online.

The long-term trend for all groups is an increase in disengagement from the news. But, again, those in the youngest age brackets and those without a university degree are more likely to say this. The proportion of 18-24s selecting ‘none of these’ in response to our survey question about news consumption has increased eight points since 2015, while the increase among those without a degree is six points. While not large, these shifts are still meaningful in the context of wider trends.

It’s also important to point out, however, that those reporting to have consumed no sources of news in our survey are not necessarily completely disconnected from information about the world around them.

People are given the option to say whether they have consumed news via print media, radio, television, or the internet in the last week. Among those saying ‘none of these’, at least some may hear about news in conversations with others or pick up on stories in their day-to-day lives. It is difficult to know for sure with our data. But other research has shown how people can be ‘incidentally exposed’ to news online, such as by coming across news unintentionally on social media (Fletcher and Nielsen, 2018).

Research which explores why many people have tuned out from the news has found a set of common reasons. In their book Avoiding the News (2024), Ben Toff, Ruth Palmer, and Rasmus Nielsen highlight sets of reasons which have to do with, first, the news media and, second, audiences themselves. Their conclusions are based on in-depth interviews with news avoiders in the UK, US, and Spain. Among the news-related (content) reasons for not consuming news, the authors note the following:

- News is doom and gloom: Why consume news when it’s so negative and depressing? In our research, we’ve found this is one of the primary reasons given for avoiding the news, along with a sense of fatigue and overload (Newman et al., 2022). People are fed up with political news, in particular, with people saying there is too much of it. They feel overloaded and bombarded by the amount of coverage, much of it negative.

- News is untrustworthy: Why engage with something you don’t trust?

- News takes too much effort: Why consume something that you feel is difficult, boring, tedious, and trivial to your life?

- News poorly represents ‘people like me’: Why consume something that makes people like you look bad?

Among the audience-related reasons for not consuming news, the authors highlight these factors:

- Genuine lack of interest: Many people just have no interest in news – and they never have.

- The stresses of everyday life: Many people just don’t have the time or energy to consume news because they are overworked, tired, and have more important things to attend to like childcare and the family budget. This adds a gender dimension to avoidance too (see Toff and Palmer, 2019).

These factors are supported by other research across various countries which has also shown news avoidance or low-to-no news consumption being related to low political interest, distrust in the news media, the perception that news lacks personal relevance or value, the difficulty of understanding or navigating the news, and feelings of anxiety or being overloaded by news (Goyanes et al., 2023; Edgerly, 2022; Toff and Nielsen, 2022; Park, 2019).

It is also important to acknowledge, however, that for some people news avoidance is a positive choice. There are many examples of people selectively avoiding the news to protect themselves from being overwhelmed by fear or anxiety, such as during the coronavirus pandemic (see de Bruin et al., 2021; Ytre-Arne and Moe, 2021; Mannell and Meese, 2022).

Again, this may not be an exhaustive accounting of the reasons why people choose to disconnect from the news, but these are some of the main factors research has uncovered so far. It is also clear how many of the factors are intertwined, with falls in consumption and interest, as well as increases in news avoidance, happening at the same time.

What should we make of all this?

The overall trend we have tracked over the last ten years has not been a positive one: consumption of online news appears to be in decline, interest in news has fallen sharply, and more people are avoiding news or choosing not to consume it at all.

These trends are apparent among many groups of people, but particularly younger audiences and those without college degrees. Gaps, while still small, are opening up between the information ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’. The implications of this include a potential decline in democratic engagement: political interest and knowledge are often crucial for political participation. Consuming reliable content is also a helpful antidote to the deluge of misinformation online: when you know what is actually true, lies have less of an impact.

While these trends are negative, they are perhaps not surprising when put in context. As we have seen, they are influenced by a number of factors: social, political, and technological. People choose to avoid the news when it becomes overwhelming or burdensome. They are put off by polarised politics. They are encouraged to consume entertainment content online, with news being de-prioritised on social media platforms.

The news media have been trying to find solutions and, in our own work, we have suggested a few. Publishers could address a wider range of topics or issues that are of interest to people, especially younger audiences. The relentless political coverage could be toned down, both in volume and negativity. The specific needs of audiences could be better addressed, making news useful and valuable. The formats or contents of news could be made more accessible or personal. Much could be done to better build your brand.

As for the public, there may be a need to recognise the importance of the social aspects of news consumption – and the role of news in society. Much news consumption is habitual or ritualised.

It was once the case that people read the newspaper at home while eating their breakfast. Or people sat down together to watch the evening news on TV. It’s unlikely that these rituals will make a roaring comeback. But the point is that news was (or is) social. Parents modelled TV news consumption behaviours to their kids. People shared the newspaper at the office. These behaviours embedded news in people’s lives, but that connection between news and audiences has frayed.

For these negative trends to reverse, there perhaps needs to be a realignment in the news media and wider society where news is again viewed as a social good, necessary for daily life and political participation. But to be that social good, it needs to be useful or valuable to people. Fixing that part is in the hands of news organisations.

Footnotes

1 Australia, Austria, Brazil, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, UK, and the US.

References

- Bellovary, A. K., Young, N. A., & Goldenberg, A. (2021). Left- and Right-Leaning News Organizations Use Negative Emotional Content and Elicit User Engagement Similarly. Affective Science, 2(4), 391–396.

- De Bruin, K., De Haan, Y., Vliegenthart, R., Kruikemeier, S., Boukes, M. 2021. News Avoidance During the Covid-19 Crisis: Understanding Information Overload. Digital Journalism, 9(9), 1286–1302.

- Dobber, T., & Hameleers, M. (2024). The Social Media Comment Section as an Unruly Public Arena: How Comment Reading Erodes Trust in News Media. Electronic News, 19312431241268012.

- Dutceac Segesten, A., Bossetta, M., Holmberg, N., & Niehorster, D. (2022). The cueing power of comments on social media: How disagreement in Facebook comments affects user engagement with news. Information, Communication & Society, 25(8), 1115–1134.

- Edgerly, S. 2022. The Head and Heart of News Avoidance: How Attitudes About the News Media Relate to Levels of News Consumption. Journalism, 23(9), 1828–1845.

- Fletcher, R. 2021. ‘Perceptions of Fair News Coverage Among Different Groups’, in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2021. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Simon, F. M., & Nielsen, R. K. (2020). Information inequality in the UK coronavirus communications crisis. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Are people incidentally exposed to news on social media? A comparative analysis. New Media & Society, 20(7), 2450–2468.

- Goyanes, M., Ardèvol-Abreu, A., Gil De Zúñiga, H. 2023. Antecedents of News Avoidance: Competing Effects of Political Interest, News Overload, Trust in News Media, and “News Finds Me” Perception. Digital Journalism, 11(1), 1–18.

- Mannell, K., Meese, J. 2022. From Doom-Scrolling to News Avoidance: Limiting News as a Wellbeing Strategy During COVID Lockdown. Journalism Studies, 23(3), 302–319.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Eddy, K., Robertson, C.T., Nielsen, R.K. 2022. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2022. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Park, C.S. 2019. Does Too Much News on Social Media Discourage News Seeking? Mediating Role of News Efficacy Between Perceived News Overload and News Avoidance on Social Media. Social Media + Society, 5(3).

- Prior, M. 2005. News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political Knowledge and Turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 577–592.

- Ross Arguedas, A., Banerjee, S., Mont’Alverne, C., Toff, B., Fletcher, R., Nielsen, R.K. 2023. News for the Powerful and Privileged: How Misrepresentation and Underrepresentation of Disadvantaged Communities Undermine Their Trust in News. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Toff, B., & Nielsen, R.K. 2022. How News Feels: Anticipated Anxiety as a Factor in News Avoidance and a Barrier to Political Engagement. Political Communication, 39(6), 697–714.

- Toff, B., Palmer, R. 2019. Explaining the Gender Gap in News Avoidance: “News-Is-for-Men” Perceptions and the Burdens of Caretaking. Journalism Studies, 20(11), 1563–1579.

- Toff, B., Palmer, R., Nielsen, R.K. 2024. Avoiding the News: Reluctant Audiences for Journalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ytre-Arne, B., Moe, H. 2021. Doomscrolling, Monitoring and Avoiding: News Use in COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown. Journalism Studies, 22(13), 1739–1755.

- Zingher, J. N. 2022. Diploma Divide: Educational Attainment and the Realignment of the American Electorate. Political Research Quarterly, 75(2), 263–277.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time