How AI-generated prose diverges from human writing and why it matters

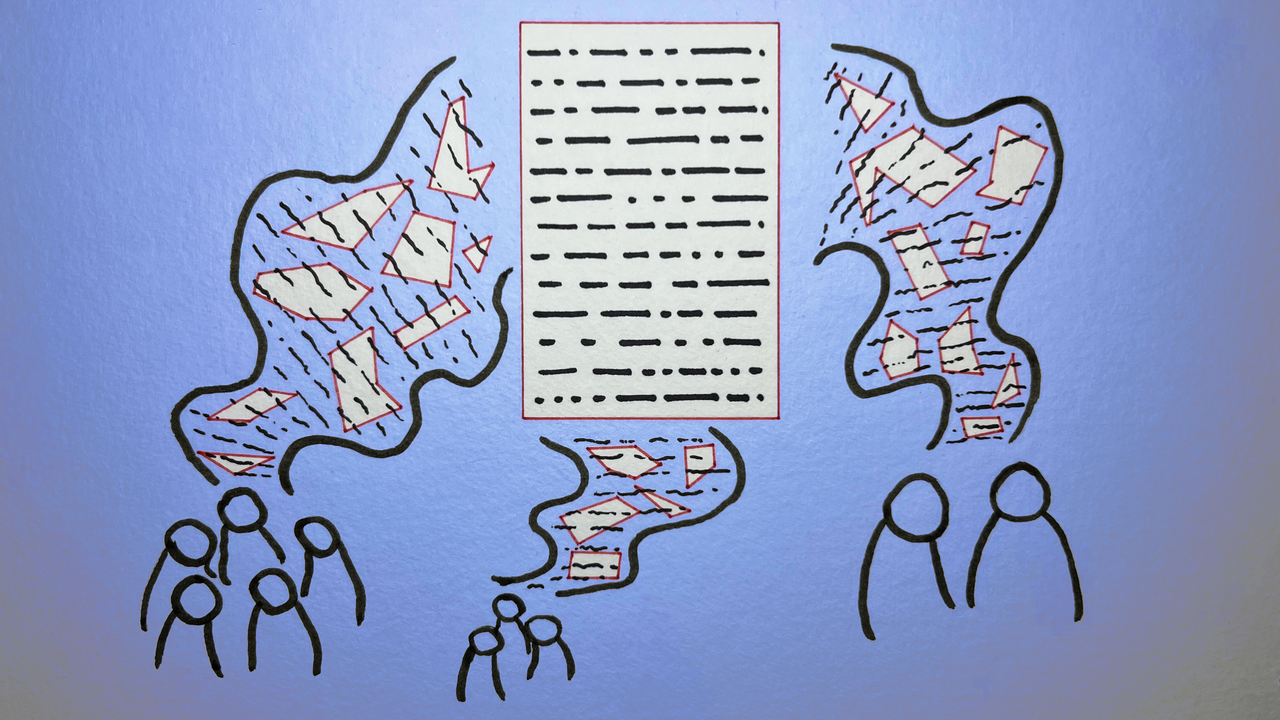

Credit: Yasmine Boudiaf & LOTI / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Delve, intricate, underscore, commendable. These English words are seeing an uptick in usage. You may also recognise them as hallmarks of ChatGPT’s prose.

Over the past couple of years, numerous observers have pointed out what they see as telltale signs of AI-generated writing. It could be previously rare words that have quickly become clichés or a formulaic sentence structure repeatedly used in the same text.

On social media, some users approach spotting AI writing as a game. In the UK, members of parliament and political journalists noted a recent increase in parliamentary speeches beginning with the phrase ‘I rise to speak’, which some have attributed to ChatGPT’s use in speechwriting. Online daters are wondering about AI writing on dating app profiles. Commenters are highlighting subtle differences in punctuation as telltale signs of AI, angering defenders of the em dash (—) and fans of 19th-century poet and prolific em dash user Emily Dickinson.

A lot of the online text we question may well be AI-generated. ChatGPT has recently hit 800 million weekly users, and 22% of the respondents of our recent survey on generative AI and news in six countries say they use it every week. According to Common Crawl data, a narrow majority of new articles on the web are authored by generative AI.

But apart from tips, hacks and intuition, is there a way to know if what you’re reading has been generated by AI? And how is AI affecting the way humans use language? I spoke to two linguists and a journalist specialised in AI and media literacy to find out what the research says, how AI could be influencing the development of the English language, and how this could impact journalism.

This discussion focuses on English as the language both at the forefront of LLM development and the main subject of linguistic research on the impact of LLMs so far. When it comes to other languages, LLMs tend to work better when there are large text databases to learn from, disadvantaging some ‘smaller’ languages, those more likely to be spoken than written down, and those where the written form differs significantly from spoken forms.

1. Is GenAI changing language?

“Especially in the popular discourse, there is a lot of jumping to conclusions, but causality is really hard to show,” said Dr Tom S. Juzek, assistant professor of computational linguistics at Florida State University.

Linguists like Juzek are working to find evidence of LLMs’ impact on language. Their work so far suggests that ChatGPT does overuse certain English words. These are often semi-formal and corporate or academic-sounding, such as ‘delve’, ‘resonate’, ‘navigate’, and ‘commendable’. These words are cropping up more and more in texts, from scientific papers to news reports.

In a paper from January, Juzek and Dr Zina B. Ward, also of Florida State University, cross-referenced words whose usage recently spiked (without an obvious reason) in scientific writing with words used more frequently in ChatGPT-generated scientific abstracts than human-authored ones. This identified a set of ‘focal words’, the increasing prevalence of which in scientific English is likely because of ChatGPT usage.

It’s important to stress that this doesn’t necessarily mean the authors of abstracts that include ‘delve’ have used ChatGPT to help write it. Separate research shows that these same words have been increasing in contexts where we can be relatively confident that there has been no LLM-generated language, such as conversational podcasts.

Research led by Dr Hiromu Yakura at the Max-Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin found that words overused by ChatGPT – the famous ‘delve’, as well as ‘comprehend’, ‘boast’, ‘swift’, and ‘meticulous’ – saw a spike in usage in conversational podcasts and academic YouTube talks after ChatGPT’s release, suggesting that these words are now used more often by humans as a result of being exposed to AI-generated content in which they are overrepresented.

“These findings suggest a scenario where machines, originally trained on human data and subsequently exhibiting their own cultural traits, can, in turn, measurably reshape human culture,” the authors write.

A student-led project at FSU, supervised by Juzek, also examined the prevalence of AI buzzwords in conversational podcasts and arrived at similar conclusions. But Juzek stressed that it’s very hard to prove that LLM-ish buzzwords are increasing in popularity because of generative AI. This is a plausible explanation, he said, but there are also other possibilities, like natural language change.

In a recent paper, also co-authored with Ward, Juzek employs a different method to get closer to the missing causal link. They took a sample of scientific abstracts, cut them in half, and tasked the LLMs Llama 3.2-3B Base and Llama 3.2-3B Instruct to generate the second half. In comparing this to the original second halves of the abstracts, they were able to identify a set of words that were likely favoured by LLMs and have also recently seen a spike in use.

Proving causality, however, would require an effective AI detector or asking authors if they used AI, Juzek said. Both of these methods also have issues: AI detectors are notoriously not foolproof, and there’s no guarantee that people would respond truthfully when asked if they’d used LLMs to write, particularly if they work in fields where this is frowned upon.

LLMs are not just increasing the popularity of some words, but also avoiding or correcting other words or constructions, according to Dr Karolina Rudnicka, assistant professor in the faculty of languages at the University of Gdańsk, Poland. When asked to review drafts, ChatGPT and the AI writing tool Grammarly both remove the phrase ‘in order to’, which is correct but can be rephrased in fewer words, she said, favouring conciseness. They also avoid slang, contractions (like 'gonna' and 'wanna'), colloquial language and passive voice.

Rudnicka’s work also shows that different LLMs have different writing styles. She compared texts on the same topic – diabetes – authored by ChatGPT and Gemini, and found that the two sets of texts showed a similar kind of distinct authorship to that of different human authors. ChatGPT tended to be more formal, while Gemini preferred more accessible language. For example, in the context of diabetes, the former used the more academic ‘glucose’, while the latter preferred ‘blood sugar’.

2. Why are certain words overused by AI?

This line of research raises an important question: if LLMs are trained on human-authored text and meant to mimic human behaviour, why does their output disproportionately use some words?

In their latest paper, Juzek and Ward suggest this discrepancy might originate in one of the stages of LLM development: reinforcement learning from human feedback. In this stage, a base model that has already been trained on a large quantity of data is refined by human annotators who rank its outputs to help predict the quality of a given response.

The human ranker is given two potential outputs and asked to pick the better one, again and again. This low-paid and repetitive work, like content moderation for social media companies, is often outsourced to the Global South, and sometimes known as ‘sweatshop data’.

This layer in AI training has been responsible for making LLMs like ChatGPT safe to use, free from swear words and offensive material. But reporting has shown that those responsible for this work received very low pay and were exposed to violent and sexually explicit material, putting them at risk of moral injury and secondary trauma.

With regards to language choice, Juzek and Ward hypothesised that the testers themselves have subtle preferences for what have become AI buzzwords, with these preferences then amplified by the training process and eventually becoming recognisable biases.

The researchers tried to replicate reinforcement learning from human feedback themselves for a base model, recruiting English-speaking testers from the Global South to try to closely mimic what big tech companies do, but paying them $15 an hour instead of less than $2. Their research found that their testers did prefer outputs that contained AI buzzwords.

3. Does it matter if GenAI is changing language?

The fact that generative AI does have a distinct writing style worries some observers. One of the concerns is the feedback loop: the idea that growing amounts of AI-generated text re-fed into new systems will reinforce existing biases and lead to an erosion of quality.

Even without taking into account new AI systems, some fear that the growth of AI-generated content on the internet, repeating the same linguistic quirks, will lead to a homogenisation of language.

So far, there’s not much evidence that homogenisation is happening, but Juzek is among those concerned.

“I share the worry, and we should keep a close eye on whether or not that is happening. When it comes to evidence for whether language will become more homogeneous, we still have to see,” he said.

However, AI is probably not singlehandedly changing the English language. According to both Rudnicka and Juzek, it’s much more likely that LLMs are accelerating language changes already underway. In Rudnicka’s view, these changes can be compared to seismic shifts in language like the advent of mass literacy in the 19th century.

In the meantime, generative AI has already challenged the assumptions behind a lot of linguistic analysis. While linguists were once safe to assume that written text reflected human language choices, this is no longer the case. This is why researchers looking at impacts on human language are using conversational podcasts, which they can more safely assume are unscripted. We can no longer take for granted that any written text hasn’t been authored, even just partly, by an LLM.

Alex Mahadevan is a journalist and director of MediaWise, the Poynter Institute’s digital media literacy programme. He also leads Poynter’s new AI Innovation Lab. I asked him, as an experienced media literacy educator, what he thought about supposedly telltale signs of AI.

Mahadevan identifies as an ‘em dash apologist’, and has always used the punctuation mark which many now associate with ChatGPT use: “It's actually been really frustrating to me, because now I have to think every time I use one of them, especially as the AI guy at Poynter, whether someone is going to think that I'm using AI to write this.”

This reflects a wider concern affecting many journalists, especially those whose newsrooms are stricter about generative AI use: will their use of a specific word, punctuation mark or sentence structure raise concerns they’re not doing the writing themselves?

Our recent survey-based report on audience attitudes towards generative AI and the news found that only a third of respondents said that they would be comfortable with the use of AI to write the text of an article, a proportion much lower than those comfortable with AI helping with spelling (55%) or writing headlines (41%).

Both findings from linguistic research and existing best practices for fact-checking would suggest it may be counterproductive to hyperfocus on specific features in a piece of writing as definitive evidence that it was generated by AI.

When suspecting a piece of text or an image has been AI-generated, “it comes back to the basic tenets of digital media literacy,” Mahadevan said, such as checking the source and seeing if the same material is referenced elsewhere.

“I do get concerned that we fixate on these quick heuristics to identify AI,” he said, as most of them, like specific words, aren’t definitive proof. The technology’s fast evolution also means that many of the small flaws that distinguished AI images in the past, for example, are no longer relevant.

4. Why should journalists care about these changes?

Some of the most identifiable AI buzzwords may already be on the path towards a decline in use. In Juzek and Ward’s experiments, recruiting humans to mimic reinforcement learning from human feedback, they note that their participants, while overall favouring AI buzzwords, tended not to prefer texts containing ‘delve’ and ‘nuanced’, possibly because they’re so often talked about as hallmarks of ChatGPT.

When it comes to journalism, one of the features of AI writing that Mahadevan finds most jarring isn’t punctuation or vocabulary, but especially ChatGPT’s tendency to “make broad, sweeping, emotional statements. For example, ‘AI in journalism isn't just a tool, it's a revolution.’”

“If you put AI-generated text in front of most editors, they will shake their heads, because it is empty. The dead giveaway for me is just that it's a lot of words that don't say anything. In journalism, we always say, ‘Show, don't tell.’”

Mahadevan worries that an over-reliance on AI writing will lead to ‘LinkedIn posts everywhere all the time’.

“If journalists lean on that, local crime stories start to read like police press releases, climate coverage starts to echo corporate sustainability reports and every homepage blurs into the same voice. That default style also tends to smooth out dialects, activist language and ways specific communities actually talk, which is bad for fair and equitable coverage,” he added.

The fact that generative AI has made sleek writing widely available also calls for a reassessment of what we take to be quality markers in a piece of writing, according to Juzek. “In the past,” he said, “people were too quick to make the link between quality of form and quality of content, and ChatGPT broke that.”

The consequences go beyond journalism and academia. Mahadevan voiced concerns about scammers, previously identifiable through typos and poor grammar in their emails, now finding it easier to fly under the radar.

But generative AI, he said, has also levelled the playing field for non-native English speakers wishing to write, for example, research papers in a global language so they may be more widely shared.

“Just because something was generated with AI doesn’t necessarily mean it is without merit,” Mahadevan said. “But there have to be ethics policies in place, and there have to be measures taken to make sure what is being generated has merit.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time