As Indian journalists' death toll reaches 474, more voices call for COVID-19 protection

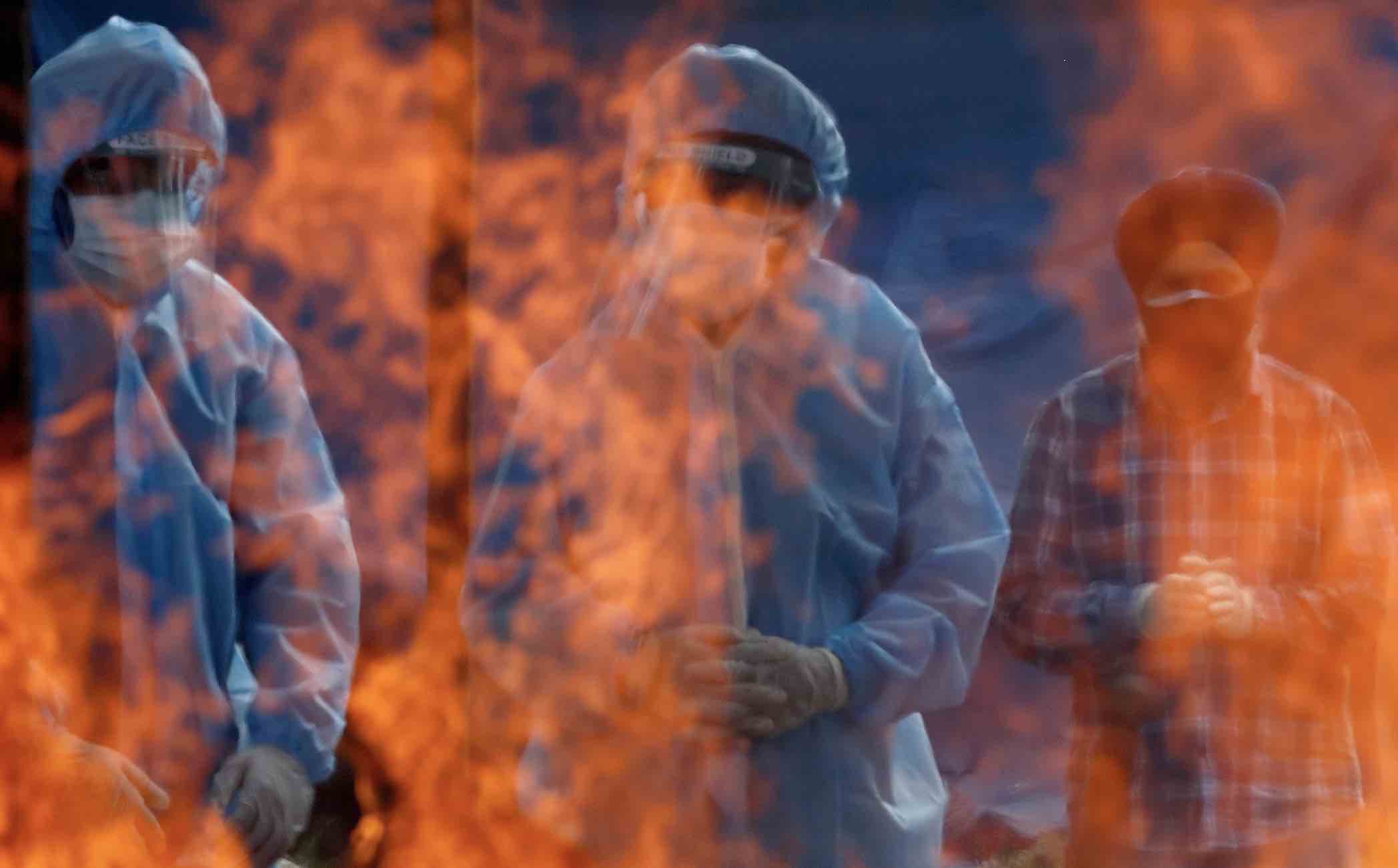

REUTERS/Danish Ismail

Journalist Pradeep Kumar, 28, helped many COVID-19 patients in Chennai access healthcare with his frontline reporting for The Hindu. When it was his turn to be helped, the journalism community tried to advocate on his behalf but it failed. His final tweet (pictured below) is a stark testament to the crisis unfolding in India in the last few weeks.

Hi @104_GoTN I'm trying to reach you urgently for an ICU bed request... Not able to connect... Pls help @mkstalin @Subramanian_ma @GSBediIAS #CovidHelp

— Pradeep Kumar (@pkayy92) May 17, 2021

By the end of May, at least 474 Indian journalists have died of COVID-19, according to a database compiled by the Network of Women in Media India (NWMI). In most cases, the deaths of these journalists were directly linked to the nature of their job: they were reporting from the field.

At greatest risk, according to award-winning journalist P Sainath, are journalists reporting from rural areas without easy access to vaccines or good healthcare. Sainath’s outlet, People's Archive of Rural India (PARI), recently reported on the death of Dadasaheb Ban, 39. Ban worked for Maratha-based daily Lokasha. His widow, 34-year-old Meena, told Pari: “He visited hospitals, testing centres and other places, and wrote about the situation on the ground. He caught the infection in late March while reporting on the second wave.”

Ban's family had to borrow money to cover a private healthcare bill of Rs1 lakh ($1,371). Despite the treatment, Ban, who had no co-morbidities, succumbed to COVID-19. He wanted his sons Rushikesh (15) and Yash (14) to study medicine. Now they face an uncertain future as the family must depend on what their mother earns with her farm.

Journalists in India say there is an urgent need for timely medical care for journalists. They ask for a vaccination plan for them similar to the ones for other frontline workers.

When Kumar died, he had not been vaccinated. Neither had Pawan Mishra, one of six journalists who died in Lucknow, waiting for a ventilator.

No social security net

At the end of May, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting announced that its Journalist Welfare Scheme would grant Rs 5 lakh ($6,858) to the kin of journalists who died of COVID-19. Some state governments – including Kerala and Tamil Nadu – have said they will also give compensations of Rs 10 lakh ($13,712).

However, R Shankar, general secretary of the Madras Union of Journalists, warns that this support is only offered to accredited journalists and accreditation is hard to come by. Even large media houses are only likely to receive accreditation for five to six members of their newsroom. “We are asking the government to give compensation for all journalists," Shankar said.

Beyond this problem, most journalists don’t work for one of the large English media houses that offer safety nets like life insurance, health insurance, and a pension. Most work for the nation’s many smaller digital and local-language outlets. They are poorly paid and unlikely to have insurance or even fuel or food allowance.

These problems are even worse for stringers and freelancers. Kavitha Muralidharan, an independent journalist working in Tamil, tells the story of 47-year-old K Manikandan, who was working as a stringer in Coimbatore for a Tamil newspaper and a news channel. “His family has received no compensation for his death as he was a freelancer," he says. Karthikeyan Hemalatha, who won a Pulitzer Centre grant for his work, agreed that freelancers are left to fight their own battles: “When I sprained my back, I was laid up for a month and had no income. I also have no health insurance or any safety net.”

Unsympathetic organisations

Any provisions once put in place to protect Indian journalists under the Working Journalists Act of 1955 have been steadily eroded by two decades of declining revenue and new business models that favour unprotected contract workers over full-time employees.

Journalists say weakened unions and a lack of protection mean many workplaces are getting away with blatant abuse, including punishing hours and a scant safety net. The Network of Women in Media India said in an official statement: "With little or no personal protective equipment (PPE), working with crippling wage cuts and threatened with the loss of their jobs, journalists have courted death daily and the roll call of those that did not make it back is rising by the day.”

Dhanya Rajendran, media entrepreneur and founder of TheNewsMinute, turned to the Committee to Protect Journalists for support in setting up protocols to protect her young newsroom. “Media houses need to ensure the safety and health of the journalists working for them,” she said. “Journalists with co-morbidities or aged parents at home shouldn't be forced to report on the ground. [...] Also with added work pressure and the looming threat of layoffs, it has become all too natural for journalists to put their personal safety at risk for that ‘important story’ or their next ‘big break’.”

Journalists under attack

All of this is finally compounded by an increasingly press-hostile government that labels journalists as "presstitutes”, “vultures” and “unpatriotic”. Top journalists like Reuters photographer Danish Siddiqui and Washington Post's Barkha Dutt have been criticised by ministers and their reporting has been called into question.

The Unlawful Activities Prevention Act of 1967 (UAPA) has been used to criminalise journalists for their work. In 2020 alone, NWMI reported, more than 60 journalists who reported on the pandemic and the plight of stranded and starving migrant workers were penalised for their work.

Among the journalists arrested under UAPA in 2020 was Siddique Kappan, who was taken into custody when covering the gang-rape of a Dalit woman in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh. “This is one of the most outrageous cases of misuse of laws and abuse of power against a journalist I have seen in 40 years,” wrote PARI founder P Sainath in an open letter to authorities, seeking his release.

When Kappan contracted COVID-19 in prison last month, he was chained to a hospital bed.

Rachel Chitra is a Journalist Fellow at the Reuters Institute. She is a finance journalist and special correspondent for the Times of India with a passion for using data to tell human stories. She has previously worked for Reuters, New Indian Express, and Deccan Chronicle, and specialises in covering banking, insurance and the capital markets. Rachel's project at the Reuters Institute will look at the documentation of lynching and rape of Muslims and Dalits in India.