In this piece

Rethinking journalism’s silence on animal agriculture

A factory-farmed pig in confinement alongside others. Credit: Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals

In this piece

Uniquely placed yet still failing | Silence is political | Science first – but with context and policy | Part of the environment, but not just the environment | Change can be tiny – yet still we miss opportunities | Beings, not bodies – mind your language | Name the powers | Talking like an animal | But what if I just ate a mozzarella stick?What does a pig say? In English, a pig says “oink, oink”. In Finnish, “röh, röh”. In Danish, “øf, øf”.

But in the language of journalism a pig is usually silent.

They would have a lot to say, if only we let them speak. And there would be plenty of them, and other farmed animals, for us to listen to: it’s been estimated that every 24 hours, between 3.4 and 6.5 billion animals are killed for food globally. A huge proportion of them spend their entire lives in factory farms.

How could journalists better incorporate nonhuman angles into stories about farmed animals? Various campaign groups have already published guidelines and training materials for journalists; with this project, I wanted to contribute to the conversation from within the industry. With the help of 12 accomplished individuals in academia, journalism, advocacy, and their intersections, this project explores what’s wrong with animal agriculture journalism and practical ways of fixing it.

Uniquely placed yet still failing

The root of the problem is deeper than what we put on the pages of newspapers. The roles humans assign to factory-farmed animals pay no heed to the species-typical behaviours, needs, or perspectives of nonhumans. Instead, the focus is on the instrumental and financial value of these animals to humans, a status quo in which nonhuman life is inherently dispensable and available for predatory commercialisation. While the media didn’t create this idea, it’s currently, by and large, reflected in and perpetuated by journalism.

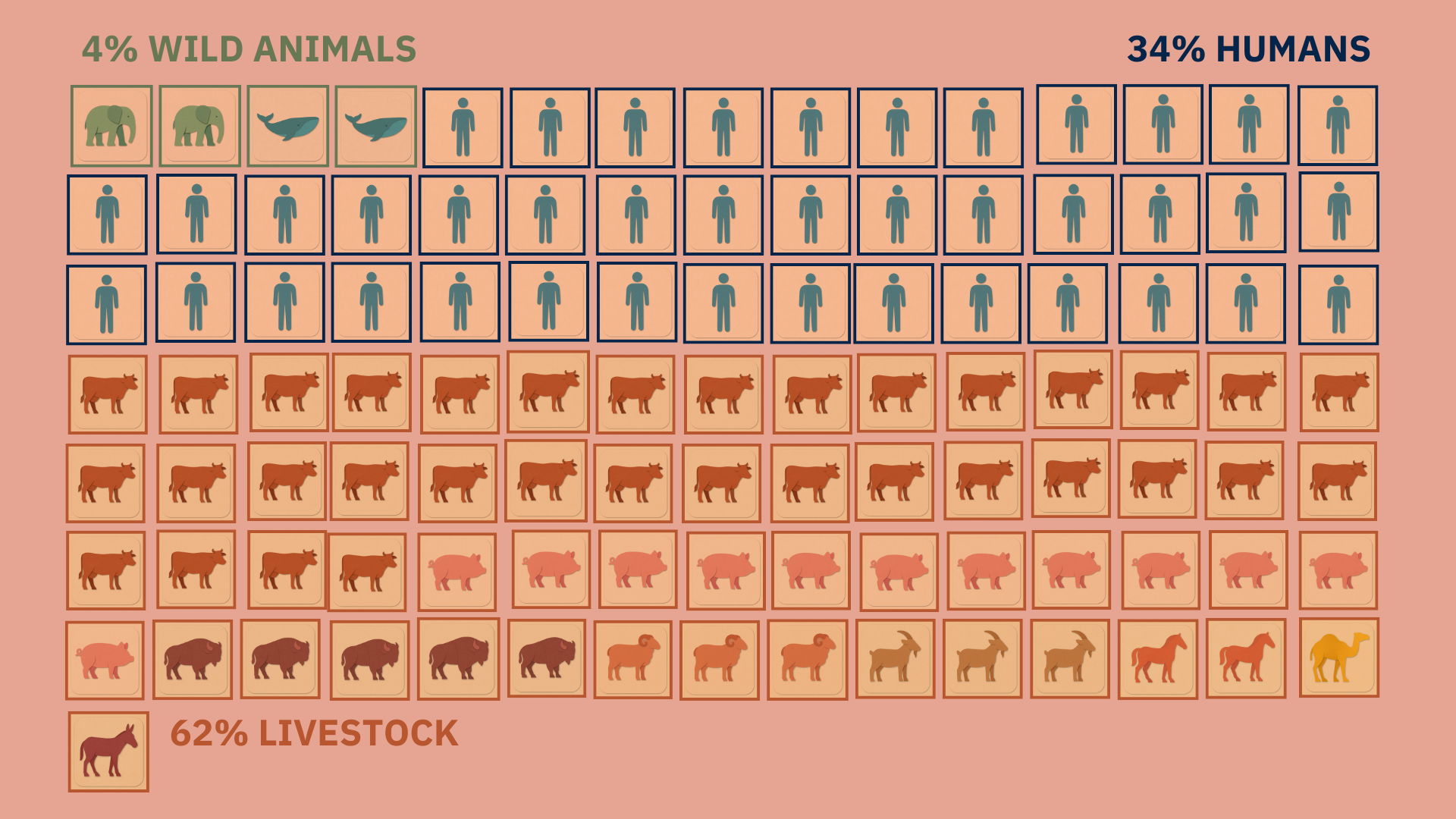

There are many reasons why the current state of affairs is unsustainable and unfair. It’s also a huge contributor to the existential threat our species is currently facing in climate change. (If you’re interested in learning more about this, read the project chapter “Animals on our plates: figures for thought”.) Journalism should be uniquely placed to shine light on how our public policies are letting down not only nonhumans but also ourselves, yet it routinely fails to do so. (More on this in the chapter “Nonhumans in journalism: figures, again”.)

How could journalists make their work fairer and more sustainable then? With the help of my interviewees, I collected eight points that can help journalists give a voice to the voiceless. These are all elaborated in the full project.

Silence is political

Ignoring nonhuman suffering is just as much a statement as being explicit about it. As one of my interviewees wisely put it, there is no moral neutrality in money or politics.

Science first – but with context and policy

An abundance of research can teach us a lot about nonhuman experiences. However, reporting on the findings requires a link to current animal agriculture policies, as science doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Part of the environment, but not just the environment

Animal agriculture has a huge impact on the climate and environment, but it’s not the only reason to reduce nonhuman suffering. Focusing only on climate impact may be harmful to the conversation.

Change can be tiny – yet still we miss opportunities

No one is expecting journalists to start reporting like they were writing for a nonhuman audience. Just acknowledge that farmed animals have a perspective and include it somewhere in the story. This is the bare minimum considering the skin they have in the game, literally, but it would be a huge step forward.

Beings, not bodies – mind your language

Privileged, human-centric vocabulary and narratives do a disservice to farmed animals. We need to carefully consider the roles we give to farmed animals in our stories.

Name the powers

The animal agriculture lobby is immensely powerful, and journalists should keep power in check. Journalism isn’t their PR.

Talking like an animal

No, a phone interview with a chicken isn’t possible, and you can’t have a veal calf as a guest on the nine o’clock news. But there is plenty of impartial information available; we just need to give it the space it deserves.

But what if I just ate a mozzarella stick?

Nonhuman exploitation is a systemic and structural issue, and solving it needs system-wide change. Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good: we all benefit from many kinds of abuse, but that shouldn’t stop us from calling it out and advocating for change.

If journalists covering issues related to farmed animals only ask themselves one question, the simplest one might be this: what does – or would – a pig say?