In this piece

Race and leadership in the news media 2020: evidence from five markets

CNN journalists Jake Tapper, Dana Bash and Don Lemon listen during a U.S. 2020 presidential Democratic candidates debate in Detroit. REUTERS/Lucas Jackson

In this piece

Key findings | General overview | Methods and Data | Findings | Conclusion | Footnotes | References | AcknowledgementsDOI: 10.60625/risj-azgk-7206

Key findings

In this Reuters Institute's factsheet we analyse the percentage of non-white top editors in a strategic sample of 100 major online and offline news outlets in five different markets across four continents, Brazil, Germany, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Looking at a sample of ten top online news outlets and ten top offline news outlets in each of these markets, we find:

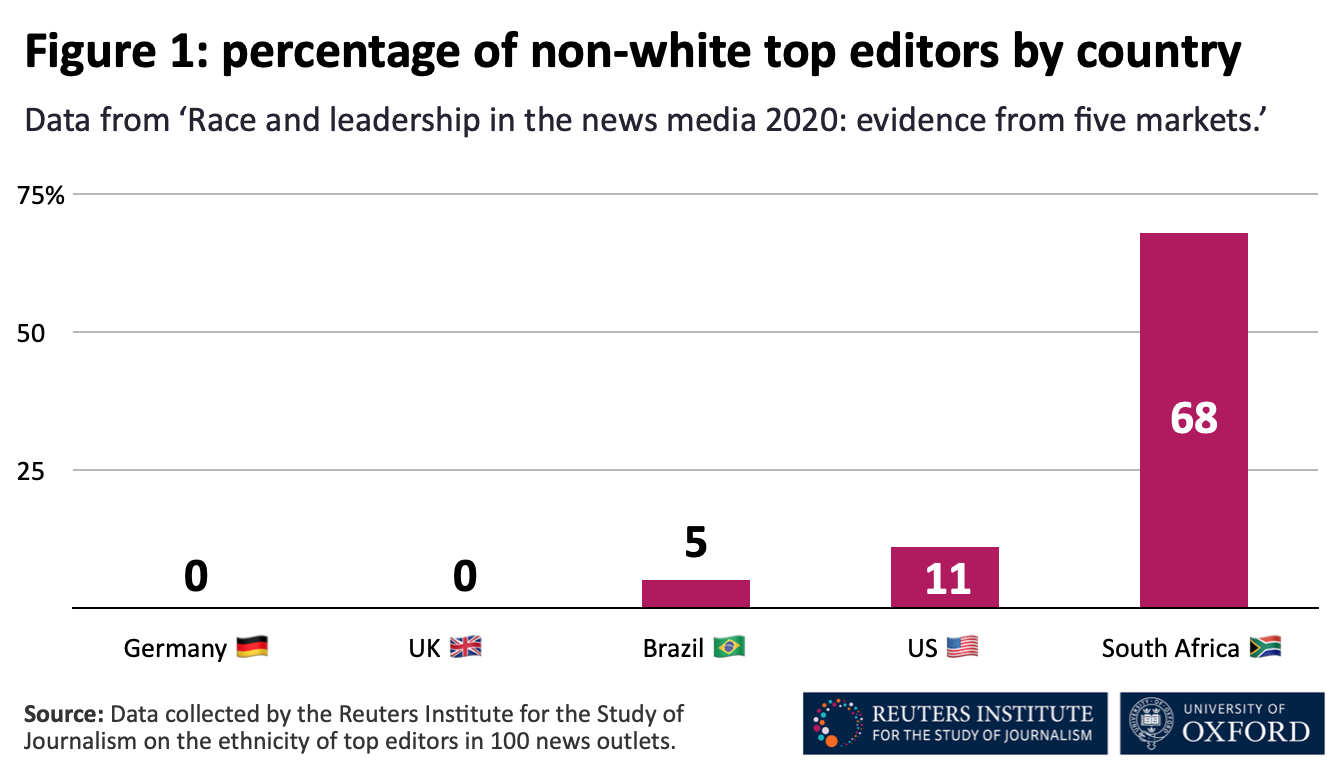

- In Germany and the UK, both home to millions of people of colour, none of the outlets in our sample have a non-white top editor. In Brazil, with a majority non-white population, we find just one non-white top editor (5%), in the US, two (11%), and in South Africa alone, a majority (68%).

- Overall, 18% of the 88 top editors across the 100 brands covered are non-white despite the fact that, on average, 41% of the general population across all five countries are non-white. If we set aside South Africa and look at the four other countries covered, 6% of the top editors are non-white, compared to, on average, 29% of the general population.

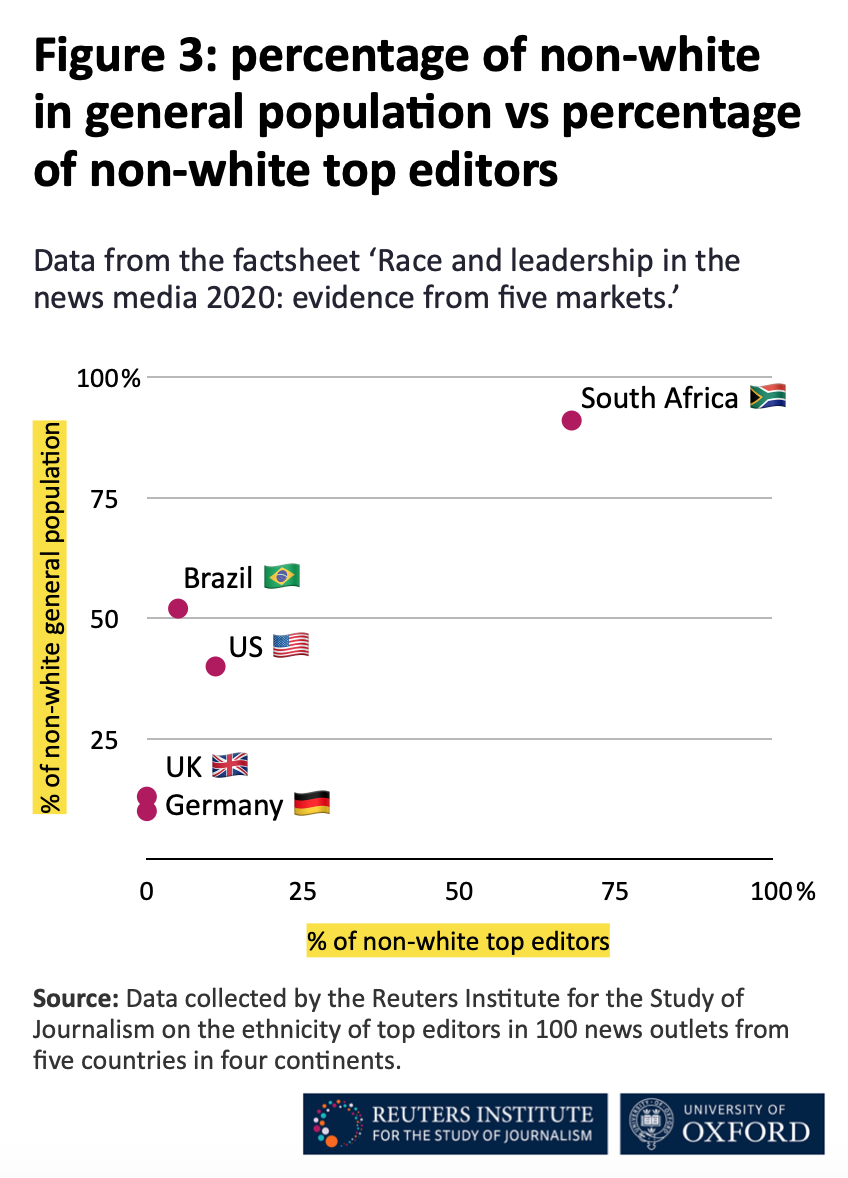

- In every single country covered, even in South Africa, which far outperforms the other four in terms of the racial diversity of top editors, the percentage of non-whites in the general population is much higher than it is among top editors.

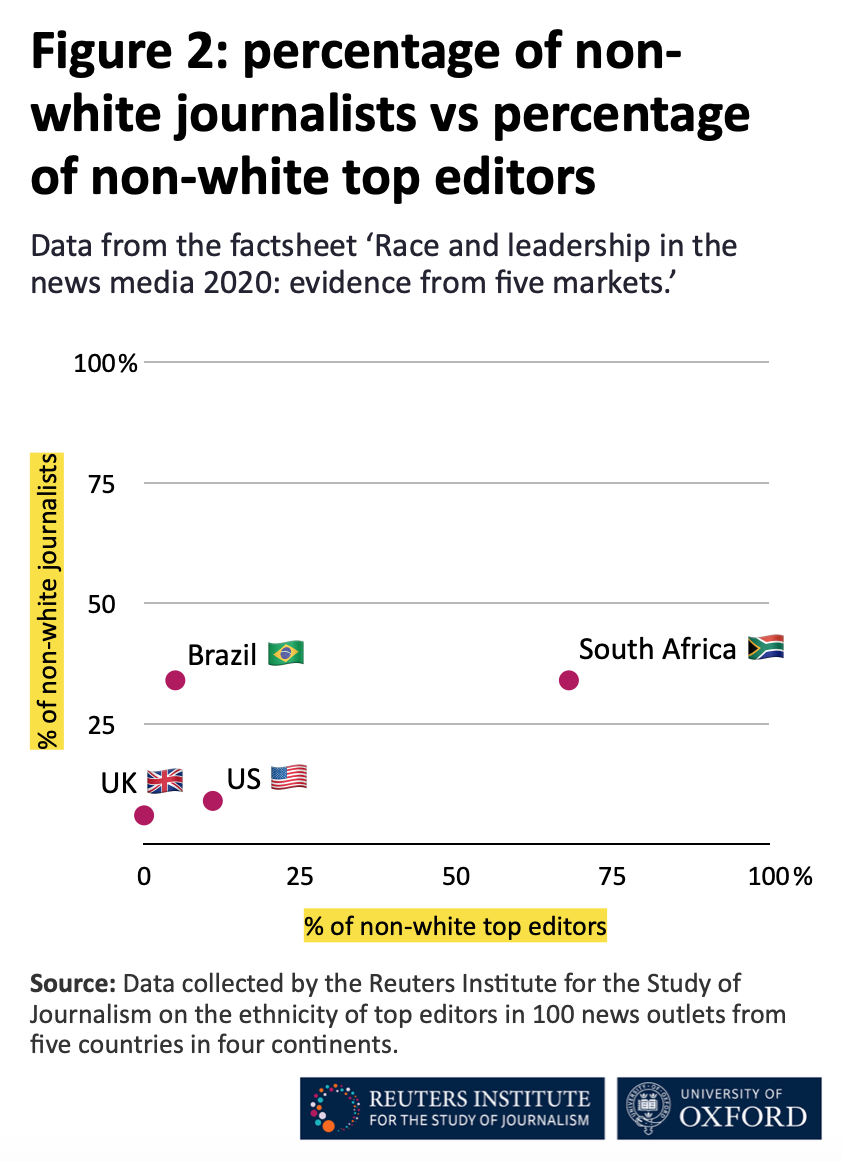

- In the four countries where data is available on the number of non-white journalists, there is no simple relation between the percentage of non-white journalists and the percentage of non-white top editors. In Brazil and the UK, there are fewer non-white top editors than there are non-white journalists, in the US, roughly similar numbers, while in South Africa, there are more non-white top editors than non-white journalists.

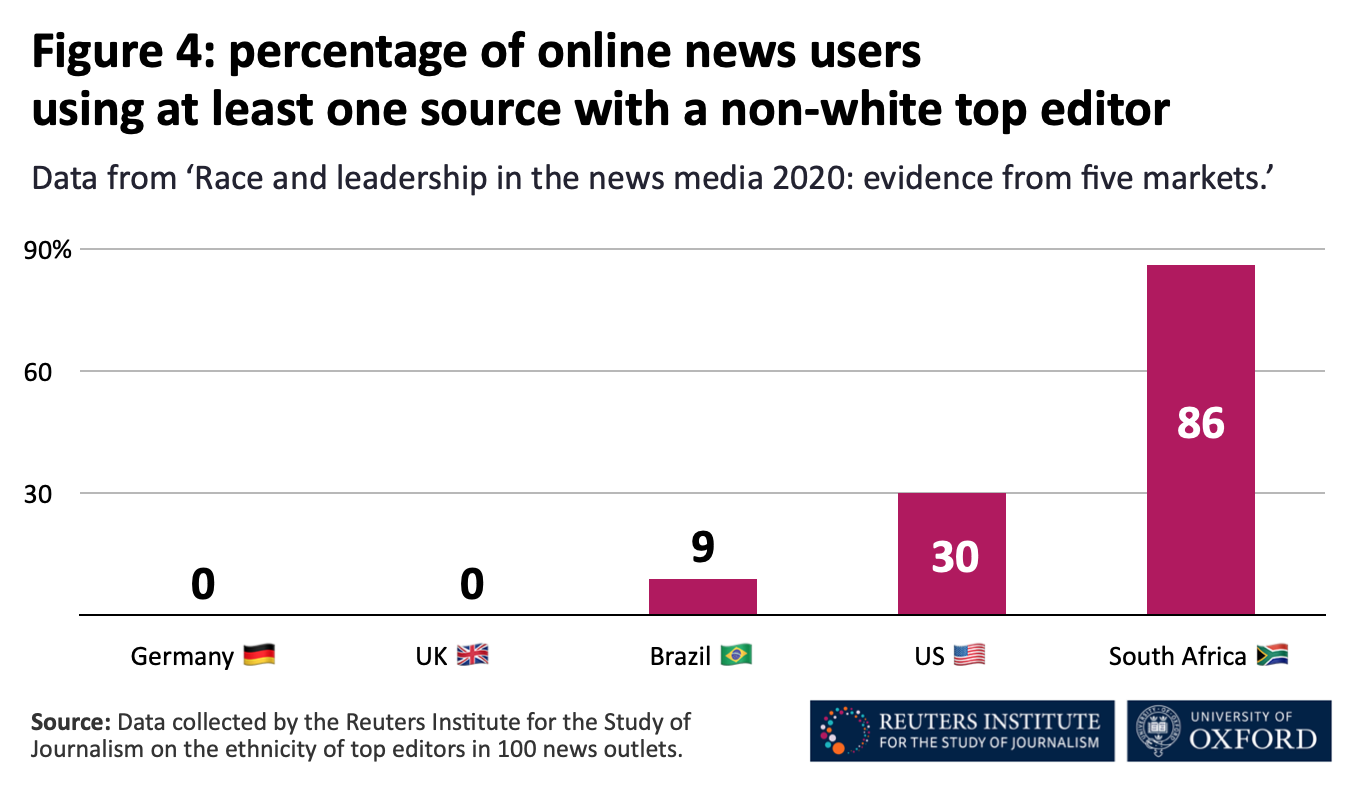

- The share of internet news users who say that they read news from at least one major outlet with a non-white top editor ranges from 0% in Germany and the UK to 86% in South Africa.

General overview

Top editorial positions in major news outlets matter both substantially and symbolically. This was the premise of our previous work on women and leadership in the news media (Andı et al. 2020), and it is the premise for this factsheet on race and leadership in the news media. Substantially, top editors make important decisions every day, and their personal experiences will sometimes be among the factors that influence these decisions. Top editors also represent their outlets, and collectively top editors help represent the news media more broadly. The diversity (or lack thereof) of top editors is thus symbolically important and likely to shape how news media are perceived by different parts of the public. That is why it is important to document the background and profile of top editors to understand more about how journalism is done and how it comes across to the rest of society (Allsop et al. 2018; Duffy 2019).

This short factsheet supplements important research conducted by others working on race in the news media. Recent studies we build on include, in the United States, the American Society of News Editors diversity survey, most recently led by Meredith Clark (Clark 2019), the Journalists in the UK report from Britain (Thurman et al. 2016), and the Diversity im deutschen Journalismus study by Neuen deutschen Medienmacher*innen in Germany (Boytchev et al. 2020). We also build on a number of important academic studies. These include, for example, Beulah Ainley (1998), who in a pioneering study in the 1990s documented how the entire British press only employed a few dozen black journalists; Cheryl D. Jenkins (2012) and others working on newsroom diversity and representations of race in the United States; and, more broadly, work like that done by, for example, Candis Callison and Mary Lynn Young (2019) on whom journalism, for whatever its other qualities, isn’t giving voice to, representing, and serving, in part due to unaddressed structural inequalities within the profession and industry itself.

Methods and Data

We examine top editorial leadership positions in a strategic sample of five markets with different demographics and different histories around race and inequality. We focus on countries shaped at least in part through different histories of white imperialism and slavery. The sample includes South Africa; Germany and the United Kingdom from Europe; the United States from North America; and Brazil from South America. To be able to leverage available data on the journalistic profession and on news and media use, we have picked the five markets from those covered in Worlds of Journalism (Hanitzsch et al. 2019) and in the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Newman et al. 2019). Where possible, we try to compare our findings to results on diversity in the journalistic profession (relying on Worlds of Journalism data) and in the wider population (relying on census data), but data is not always available and comparisons therefore are not always possible. This is in part because of a dearth of research, but also in some cases compounded by legal restrictions on collecting and retaining certain statistics on race (in for example Germany).

In each market, we focused on the top ten offline (TV, print, and radio) and online news brands in terms of weekly usage, as measured in the 2019 Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Newman et al. 2019). (Our focus on the most widely used offline and online brands means that some important outlets are not covered. For example both the Financial Times in the UK and Vox in the US have women of colour as editors-in-chief, but they are not included in the sample.)

For each brand, we identified the top editors by checking their official webpages. The data was initially collected in February 2020 for our previous work on gender, and all names validated in July 2020. Four editors had moved on or been replaced. When unable to detect who the top editor is we looked for editor-in-chief or nearest equivalent e.g. executive editor, head of news for TV. The exact terminology varies from country to country and organisation to organisation, but in most cases it is possible to identify a single person. We coded observations as missing in cases where both online and offline versions of the same brand share a top editor, so the analysis covers a total of 88 individuals across the 100 brands included. We refer to them collectively as the top editors. It is important to note that this of course does not imply that the top editor is the only person who matters, or even is always in fact the most important person in terms of day-to-day editorial decision-making.

The individuals identified were double-checked by journalists from the market in question who have been Journalist Fellows at the Reuters Institute, as well by our researchers. We also contacted the brands or their press offices to confirm who is their top editor. Where organisations responded, we always defer to their judgement. In some cases where an organisation has not responded to our query, and where there is no single clear designated editor-in-chief, or roles and responsibilities across online and offline parts of the same outlet are unclear, we have made a judgement call as to who to code as the top editor of the outlet in question.

Following recent work on the representation of race in editorial positions in the field of communications research (Chakravartty et al. 2018), we operationalised race through a narrow conception focused on documenting differences between institutionally dominant white populations and dominated non-white populations. Race and racial discrimination work in complex ways not always tied to skin colour, for example where it has a religious dimension. But white/non-white capture some important aspects of this in the countries we cover. We therefore deploy a simple and reductionist, but hopefully still illuminating and relevant, binary, and code each top editor as white or non-white. Non-white is not meant to suggest an identity, let alone a homogenous group, but provides a way to categorise otherwise very different people who come from dominated ethnic and racial groups.

All individuals in the dataset were coded independently by the three authors (who come from different countries and have different racial identities), and all codes for Brazil and South Africa were double-checked with journalists from the two countries. In the end, all codes were the same, so the inter-coder reliability score was 1.0. Race and ethnicity are complicated phenomena and so are statistics on race and ethnicity. All the numbers presented here, both those from our own data collection and those from secondary sources we rely on, should be seen with this in mind.

Findings

As is clear from Figure 1, the percentage of non-white top editors vary significantly in our sample of countries. In Germany and the UK, none of the outlets covered have a non-white top editor. In Brazil, just one (5%), in the US, two (11%), and in South Africa alone, a majority (68%).

The countries covered are thus very different. Overall, we find that 18% of the 88 top editors across the 100 brands covered are non-white. This is below the average percent of non-white journalists (21%) in the four countries where data is available from the Worlds of Journalism project (Hanitzsch et al. 2019). It is well below the average percent of non-whites in the general population across all five countries as reported in official census data and estimates (41%).1 If we set aside South Africa and look at the four other countries, across them, 6% of the top editors are non-white, compared to, on average, 29% of the general population.

When looking at the relation between the number of non-white journalists and the percentage of non-white top editors relying on data from the Worlds of Journalism project (Hanitzsch et al. 2019), we find a mixed picture (Figure 2).2 The UK has a small number of non-white journalists in the profession at large (6%), but no non-white top editors in our sample. In Brazil, a third (34%) of journalists are non-white, but only one top editor in our sample is non-white (5%). In the US, the percentage of non-white journalists (9%) about match the percentage of non-white top editors in our sample (11%) (but both numbers are far below the percentage of non-whites in the general population, as we show below). In South Africa, there are fewer non-white journalists (34%) than there are non-white top editors in our sample (68%).

Comparing data on the demographics of the population as a whole with the percentage of non-white top editors gives us a broader sense of racial inequality at the very top of journalism in these countries (Figure 3). It is striking here that in every single country covered, even in South Africa, which far outperforms the other four in terms of the racial diversity of top editors, the percentage of non-whites in the general population is much higher than it is among top editors.

The gap takes different forms in different countries. It is biggest in percentage points in Brazil, which has a majority non-white population (52%) but only one (5%) non-white top editor in our sample. The gap is very large in both South Africa (91% versus 68%) and the United States (11% versus 40%), in both cases almost 30 percentage points. The gap is numerically smaller in Germany and the UK, but in a way even more glaring given the absence of any non-white top editors in our sample in countries with significant non-white minorities.

Finally, by combining the data collected for this Reuters Institute factsheet with data from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Newman et al. 2019), we can determine how many people in each market covered access news from at least one major news outlet with a non-white top editor. As can be seen in Figure 4, the share of respondents who say that they read news from at least one major outlet with a non-white top editor ranges from 0% in Germany and the UK to 86% in South Africa. In four of the five countries covered, the vast majority of online news users do not regularly use any brands with a non-white top editor.

Conclusion

In this Reuters Institute's factsheet we have analysed the racial break-down of top editors at a strategic sample of 100 major online and offline news outlets in five different markets across four continents. Relative to their share of the general population, whites are significantly overrepresented among top editors in all five countries, and non-whites significantly underrepresented. All or nearly all top editors in our sample in most of these countries are white. South Africa is the only country where this is not the case, with 68% non-white top editors and 91% non-white population. Of the countries covered, it has the smallest discrepancy between the racial demographics of top editors relative to the general population, though whites, who make up 9% of the population according to the 2011 census, still occupy 32% of top editorial positions in our sample.

In all the four other countries, the discrepancies are much bigger in relative terms. In Germany and the UK, we did not find any non-white top editors in our sample, though both countries are home to millions of people of colour. In Brazil, where the 2010 census found that 52% of the population is non-white, only one top editor in our sample (5% of the total) is not white. In the United States, where other research (e.g. Clark 2019) has documented some modest progress in both the rank-and-file of the journalistic profession and in leadership positions in recent years, the top jobs are still overwhelmingly held by whites, even as the US population grows more and more diverse. But in the US too, historical trends are concerning. Comparing data on American journalists with census data shows that non-whites were about one-third the share of the journalistic profession that their share of the general population would suggest from the early 1970s till the early 2000s, but that the figure has since declined to about one-quarter (Willnat et al. 2014). While the US population has grown proportionally less white, US journalism has grown disproportionally more white.

The US example is instructive. The lack of diversity in journalism there has been subject to increasingly intense critical scrutiny, at least since the civil rights movement and the Kerner Report in 1968, scrutiny that has been constantly maintained by groups representing minority journalists, and occasionally discussed more widely in the aftermath of crises like that surrounding the police beating of Rodney King in 1991 and more recently the police killing of George Floyd in 2020. The American Society of Editors and others have recognised the problem and stressed the need for greater diversity for decades, in line with the Kerner Report more than half a century ago, stressing the need to ‘hire more black journalists and promote black journalists to decision-making roles’ (National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders 1968, p. 385).

Despite this, progress has often been incremental at best, and sometimes reversed. The years following the financial crisis, for example, saw a sustained decline in the number of minority journalists in US newsrooms as thousands were laid off in ways that further exacerbated racial inequalities (Anderson 2014). There is a real risk that the impact of the coronavirus crisis could have the same effect, even as some US newsrooms are trying to increase diversity among their journalists and editors.

Will they, and counterparts elsewhere, including Germany and the UK, where we find no non-white top editors in countries with significant non-white populations, deliver? We will know more when we repeat this analysis in 2021 to track developments in race and equality among top editors across the world.

Footnotes

1 For information about the general population, we have relied on official census data where possible, namely the 2010 census in Brazil, the 2017 mini-census in Germany, the 2011 census in South Africa, the 2011 census in the UK, and the 2019 US Census Bureau population estimate. Race does not have the same history or work the same way in all these countries, a complexity we set aside here to enable cross-national comparison. German law prohibits the collection of official statistics along ethnic categories, a practice that has important historical reasons behind it but has also been subject to some criticism. (‘[If] you’re not counted, then you don’t count’, as Daniel Gyamerah has put it.) To arrive at an approximate figure for comparison, we have aggregated census data on migrants with a Middle Eastern/Northern African/Central Asian, Sub-Saharan African, East Asian and South/Southeast Asian, Other/unspecified/mixed background.

2 We are grateful to the Worlds of Journalism project for sharing the data. Their fieldwork in Brazil was led by Sonia Virgínia Moreira and conducted from 2014 to 2016, in Germany by Thomas Hanitzsch, Nina Steindl and Corinna Lauerer from 2014 to 2015, in South Africa by Arnold S. de Beer, Sean Beckett, Vanessa Malila, and Herman Wasserman in 2014, in the UK by Neil Thurman and Jessica Kunert in 2015, and in the US by Tim P. Vos and Stephanie Craft in 2013.

References

- Ainley, B. 1998. Black Journalists, White Media. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

- Allsop, J., Ables, K., Southwood, D. 2018. ‘Who’s the Boss?’, Columbia Journalism Review, Spring/Summer.

- Anderson, M. 2014. ‘As News Business Takes a Hit, the Number of Black Journalists Declines’, Pew Research Fact Tank, 1 Aug.

- Andı, S., Selva, M., Nielsen, R. K. 2020. Women and Leadership in the News Media 2020: Evidence from Ten Markets. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Boytchev, H., Horz, C., Neumüller, M. 2020. Viel Wille, kein Weg: Diversity im deutschen Journalismus. Cologne: Neuen deutschen Medienmacher*innen.

- Callison, C., Young, M. L. 2019. Reckoning: Journalism’s Limits and Possibilities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chakravartty, P., Kuo, R., Grubbs, V., McIlwain, C. 2018. ‘#CommunicationSoWhite’, Journal of Communication 68(2), 254–66.

- Clark, M. D. 2019. How Diverse are US Newsrooms? Columbia, MO: American Society of News Editors.

- Duffy, A. 2019. ‘Out of the Shadows: The Editor as a Defining Characteristic of Journalism’, Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919826818

- Hanitzsch, T., Hanusch, F., Ramaprasad, J., de Beer, A.S. (eds). 2019. Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures around the Globe. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Jenkins, C. D. 2013. ‘Newsroom Diversity and Representations of Race’, in C. P. Campbell, K. M. LeDuff, C. D. Jenkins, R. A. Brown (eds), Race and News: Critical Perspectives. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. 1968. Kerner Report. Washington DC: National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Nielsen R. K. 2019. Digital News Report 2019. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Thurman, N., Cornia, A., Kunert, J. 2016. Journalists in the UK. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Willnat, L., Weaver, D. H., Wilhoit, G. C. 2017. The American Journalist in the Digital Age: A Half-Century Perspective. New York: Peter Lang.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Caithlin Mercer, Daniela Pinheiro, and Richard Fletcher for their valuable time, input and feedback, and Thomas Hanitzsch and the Worlds of Journalism project for sharing their data.

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

This report can be reproduced under the Creative Commons licence CC BY. For more information please go to this link.