“Journalists shouldn’t drift towards activism. Our job is to hold power to account”

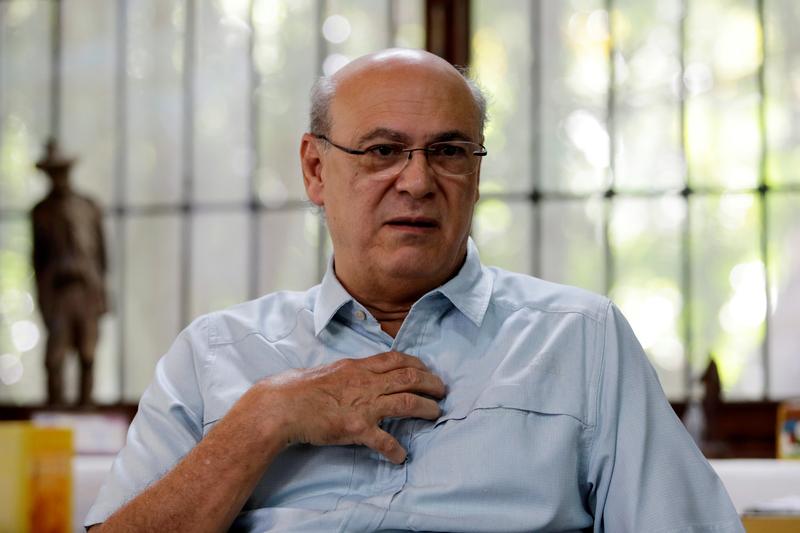

Journalist Carlos F. Chamorro, speaks during an interview with Reuters in 2018. REUTERS/Oswaldo Rivas

The life of Carlos F. Chamorro changed forever when his father was murdered in 1978. Pedro Joaquin Chamorro Cardenal, a well known figure in Nicaragua, was the editor of La Prensa, a daily newspaper. He was also one of the fiercest critics of Anastasio Somoza's dictatorship.

After Pedro Joaquín’s murder, his son Carlos abandoned his plans to study a masters degree in economics and enrolled in journalism and politics. He joined both La Prensa and the Sandinista Front, the party which ousted Somoza and was in power from 1979 to 1990. “I saw journalism as an instrument of change against the dictatorship”, he says.

In the early 1990s, Chamorro was the editor of Barricada, a newspaper owned by the Sandinista Front. In 1994 he was fired along with some of his colleagues after publishing news stories the party’s leadership didn’t like. In 1995 he launched Esta Semana, his own TV programme. A year later, he founded Confidencial – first a magazine, now a news site with newsletters in English and Spanish.

Born in Managua in 1956, Chamorro was forced into exile in 2021 along with many other journalists by Daniel Ortega, a former Sandinista leader who has jailed dozens of activists and opposition leaders since getting back to power in 2007. Ortega’s regime raided Chamorro’s newsroom and seized his property. Earlier this year, Ortega also stripped Chamorro of his Nicaraguan citizenship along with intellectuals and activists such as Dora María Téllez, Sergio Ramírez and Gioconda Belli.

On Monday 6 March, Carlos F. Chamorro will deliver the 2023 Reuters Memorial Lecture, the most important event the Reuters Institute hosts every year.

With Ortega’s latest repressive measures still in the headlines, I spoke with Chamorro, who lives in San José, Costa Rica, where most Nicaraguan journalists are now based. We discussed the challenges of reporting from exile, the ups and downs of his career and the decline of press freedom in Central America. Our conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity. You can watch the event on our Memorial Lecture webpage.

Q. At the end of the 1970s, you decided to enrol in both journalism and politics. Why?

A. I saw journalism as an instrument of change against the dictatorship. But mixing journalism and politics never worked. Journalism always loses out when faced with the imperative of politics. And this was even more so in the midst of a war of external aggression that imposed a series of restrictions on the exercise of freedoms. We suffered from censorship and self-censorship in Nicaragua throughout the 1980s. We tried to do journalism. But politics was always in the way. I believe I only became a true journalist later, when I again faced this dilemma between journalism and politics. Then I said: “No. I don’t want to have a political career. What I want is to do journalism.”

Q. When did you face that dilemma?

A. It happened in 1990, when another big change took place in Nicaragua. The Sandinista Front lost the election and my mother, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, initiated a democratic transition. At the time I was the editor of Barricada, a newspaper owned by the Sandinista Front, and we wanted to transform it into a professional newspaper at the service of its readers. But three or four years later, I was fired. Then I decided to create my own news outlets.

Watch Carlos's lecture

Q. From 1990 Nicaragua experienced a golden age of press freedom. How do you remember those years?

A. We must give credit to my mother, who [defeated the Sandinista Front and] made press freedom one of her key policies. She was convinced that press freedom was essential. Journalism became much more professional. Newspapers competed with each other on their ability to hold power to account. My mother’s government was one of the most scrutinised in Nicaragua’s history by journalists exercising these freedoms.

Q. How did that golden age of press freedom come to a close?

A. That golden age spanned 16 years and included the governments of Barrios de Chamorro, Arnoldo Alemán and Enrique Bolaños. In those years, a free press and civil society flourished. Without the strength of civil society the press wouldn’t have been as strong. We believed this was irreversible and this was a mistake. Everything changed when Daniel Ortega returned to power in 2007. There were many promises that there would be no censorship, but this did not last.

For me the clearest sign that something was wrong arrived when we published Blackmail in Tola. It was the first major corruption scandal of the Ortega regime: a story about politicians offering to solve legal problems for businessmen in exchange for millions of dollars. The scandal was huge, but Ortega didn’t order an investigation into the scandal. He launched an inquiry into our own sources and even accused us of drug trafficking. For me that was a clear warning.

Then came electoral fraud and a gradual dismantling of the rule of law. Between 2007 and 2017, Ortega tolerated a critical press because he didn’t feel threatened. But everything collapsed with the protests in April 2018.

Q. A key difference between today’s repression and the one your father suffered in the 1970s is the presence of the internet as a tool for freedom. To what extent has this factor helped journalism in Nicaragua?

A. Newspapers and radio stations have always carried a lot of weight in Nicaragua. However, between 2007 and 2017, television was the key medium and also the one the regime tried to control the most. In 2010, for example, Ortega used Venezuelan money to buy a private channel where I presented a programme. As a result, I was forced to leave.

Then Ortega created a big group with television channels, radio stations and news sites. When protests began in April 2018, the first thing the regime did, apart from launching physical attacks against journalists and killing journalist Ángel Gaona, was to impose TV censorship.

During those months, cell phones and internet connection were key to covering the protests. We curated and verified posts from social media and told stories of repression and resistance. When the regime removed me from TV, we continued broadcasting through a YouTube channel that today has more than 400,000 subscribers. Social networks were essential to defeat censorship, but they also became a space for polarisation and misinformation.

Q. This is a phenomenon that we’ve seen in countries as different as the United States, Brazil and the Philippines. Have you experienced this in Nicaragua too?

A. Social media has always been a disputed space. In the case of Nicaragua, though, I would say the regime has never had the upper hand. The regime has used troll farms and its own disinformation platforms, but a national majority has spoken up against the repression on social media and will continue to do so.

Ortega is not Nayib Bukele, [a politician who serves as El Salvador's President and who’s social media savvy]. Neither Ortega nor his vice president Rosario Murillo has a Twitter account. The regime has criminalised freedoms and assaulted the media. That’s what happened with Confidencial and with Nicaraguan news site 100% Noticias in December 2018. The police arrived, stole our equipment and occupied our newsroom. A year later, the same thing happened with La Prensa, a daily newspaper.

Then the regime passed the so-called cyber crime law, which threatens those who disseminate information that causes anxiety, moral damage or instability with up to four years in prison.

More than 30 people have been sentenced under that law, including several priests and the Bishop Rolando Alvarez, who is still in jail today. There was even a farmer sentenced who did not have any social networks. The regime created them later to justify his conviction.

Q. How do you manage to practise journalism in such a difficult environment?

A. Practising journalism today in Nicaragua from exile, where almost all journalists find ourselves, requires two things: protecting journalists and protecting sources, which need to remain anonymous in any pieces we publish. I'm talking about lawyers, economists, legal experts, health experts, priests. Anyone who speaks to journalists may be subject to retaliation by the regime.

Q. You have been living in exile for a few years. How do you manage to find out what is happening in the country?

A. First of all, anything we publish must be double-checked and triple-checked. Some people use their anonymity to give opinions and not proven facts. Our standards must be even higher than usual.

Secondly, we must make an effort to cultivate sources that can tell us what’s happening within the regime. It’s important to know the impact repressive measures have on the police, the prison system or the judicial system. We don’t know everything. But we do have a few sources that have been instrumental in providing reliable information that allows us to continue investigating corruption and human rights violations.

Journalism in exile is at risk of living within its own bubble. Of course we tell the stories of Nicaraguans in exile. But our primary goal is to cover the Nicaraguan crisis from within the country.

Q. In this difficult context, how is your relationship with other Nicaraguan news outlets?

A. Since protests broke out in April 2018, there has been a process of collaboration. We created a forum where all independent news outlets are represented. We collaborate in different ways. We help each other when needed in terms of physical safety. We also share news stories from other newspapers and help them broaden their reach. Of course, each news organisation wants to preserve its own style and its own identity. But we’ve collaborated a lot and we’ve worked with other outlets to investigate cross-border issues.

Q. In his memoirs, Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramírez says that what happens in a Central American country often influences what happens in others. Authoritarianism is now on the rise in countries like El Salvador or Guatemala. Is press freedom also threatened in those countries?

A. First of all, I would like to highlight the strength of the democratic institutions of Costa Rica, which has been a shelter for journalists and politically persecuted people in the region and beyond. My father was in exile in Costa Rica from 1957 to 1959. When I arrived here in my first exile in 2019, I found great solidarity from news organisations such as Teletica, Channel 7 or La Nación. Several broadcasters opened their doors for us so that we could do journalism from here.

Secondly, I would say that Nicaragua today is a mirror for other countries in Central America, and especially for our colleagues from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. Nicaragua is a country where the rule of law has already collapsed. In Guatemala and El Salvador there is a restricted and defective rule of law, but the rule of law still exists. Journalists in those countries do their jobs in an emergency context, but they haven’t been forced into exile yet.

Exile for Nicaraguan journalists is not a temporary condition but a permanent condition. No other Central American country is going through the same situation yet. But we share experiences with media colleagues like Contracorriente in Honduras, El Faro in El Salvador or Contrapoder and El Periódico in Guatemala, whose founder José Rubén Zamora has been in prison for months.

Survival of journalism in authoritarian regimes depends on us. When the rule of law collapses, everything depends only on our credibility and the quality of our work.

Q. What would you say is on the horizon for free journalism in Nicaragua?

A. The horizon is very uncertain. The regime has stripped me and other journalists and activists of our citizenship. They seized our property time and again. But they’ve never been able to seize journalism. As journalists, we shouldn’t drift towards activism. Our job is to hold power to account. We shouldn’t drift towards activism. We should keep doing quality journalism. That’s our main challenge.

Even today we can still practise journalism. We do it with enormous difficulties, but it’s still possible to do it. In a country like Nicaragua, where there is no freedom of assembly or movement or religion, we journalists continue to report with the help of the internet and social media. We don’t accept censorship or self-censorship. If the press preserves its credibility, we will preserve our freedoms.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time