Jailed, exiled and harassed, journalists defy authoritarian leaders in Central America

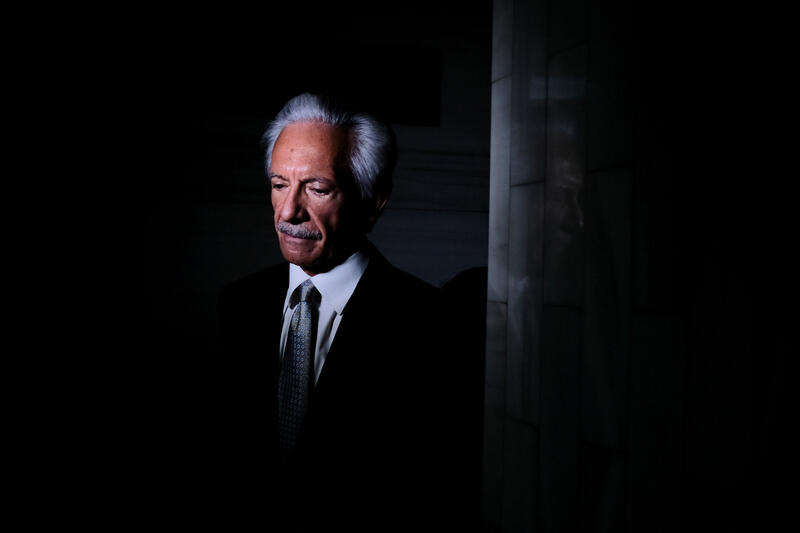

Journalist José Rubén Zamora, founder and president of elPeriodico, after a court hearing in Guatemala in 2022. REUTERS/Josue Decavele

Editor's note: this piece has been updated to reflect elPeriódico's announcement that it's shutting down.

El Faro is one of El Salvador’s most prominent news outlets and a reference for independent journalism across Central America. So when its founders announced in April that it had found a new home outside of the country, many voices saw it as a bad omen for press freedom in a region where journalism has been under pressure for too long.

Ant yet this was not the first warning. In neighbouring Guatemala, José Rubén Zamora, president of the elPeriódico newspaper, was arrested in July 2022 on charges of money laundering, blackmail and influence peddling. He has been in jail ever since.

On Friday 12 May, Zamora's colleagues announced that the newspaper will be forced to shut down due to government pressure. They explain that nine of their journalists are being investigated, four of their lawyers have been arrested and two are still in jail. "We'll keep believing in a Guatemala where justice and free speech are possible, a country where democracy can flourish," they say.

?? Aviso importante a nuestros lectores, anunciantes, sociedad en general y comunidad Internacional. ⚠️ pic.twitter.com/jt0Z8Y8gMc

— elPeriódico (@el_Periodico) May 12, 2023

Driving an outlet to exile

Founded 25 years ago, El Faro has registered as a non-profit in Costa Rica. While the main newsroom will remain in El Salvador, its legal and administrative operations have been forced out of the country due to what they describe as a relentless campaign of government harassment.

El Faro’s move marks the latest sign of a continuing decline of press freedom in Central America, a region that is one of the most dangerous for journalists and a place where news publishers are facing government harassment, delegitimisation, and complex legal challenges. For this piece, I spoke to three journalists from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to assess the extent of the decline of press freedom in each country and in the region as a whole.

For Sergio Araúz, El Faro’s deputy editor-in-chief, moving their administrative and legal operations to Costa Rica is a “shield” protecting them against the ongoing harassment they are facing in the country at the hands of President Nayib Bukele. “Our permanence as a media outlet could only be conceived in a democratic system with independence of powers,” he says.

El Salvador has experienced a sharp dismantling of its press freedoms ever since the election of Bukele in 2019. Before he rose to power, the country stood at 66 in the RSF's World Press Freedom Index. By 2023, El Salvador has fallen to 115 out of 180 countries. President Bukele has attacked journalists relentlessly and created a hostile environment for them to operate in, with actions ranging from espionage to discreditation.

An independent investigation revealed in 2022 that over 35 activists and journalists were monitored for more than a year with the Pegasus spy software, whose Israeli developer sells exclusively to governments. The investigation also revealed that hacking took place while journalists were reporting on sensitive issues involving Bukele’s administration. Once installed on a device, Pegasus can monitor text messages, search histories, GPS locations, and even turn on the device’s microphone and camera to record conversations without detection.

“When we read these expert reports, we saw that they have our life because they’ve had access to our conversations,” said Araúz, who is identified as one of the victims in the report.

The Pegasus hacking scandal took place against a backdrop of other attacks against the press in El Salvador. Journalists have been prevented from covering protests and visiting homicide scenes, and they have being frequently barred from accessing government conferences.

Bukele routinely attacks journalists from his podium. He devoted a two-hour press conference to denigrating and condemning independent media. He has referred to journalists as “political activists” multiple times and has suggested they are corrupt. A special report by the Reuters news agency even uncovered how the Bukele government has employed paid influencers, trolls, and “probably bot farms” to create and engage in pro-government messaging on social media.

Araúz says that these tactics are used by the government as methods to “despise or delegitimize” independent media outlets like them. “In El Salvador, El Faro has the connotation, thanks to the president and all his spokespersons, of being a kind of opposition,” says Araúz. “This is another way of making us vulnerable: the delegitimization or this label that the President has placed on us.”

The law as a weapon against journalism

Legal challenges against journalists in the region have also been ramping up. They have also become more complex and insidious than ever before. In El Salvador, the government has opened an investigation on money laundering charges against El Faro. This is a tactic intimately familiar to Guatemalan journalist José Carlos Zamora, whose father José Rubén Zamora is currently behind bars in pre-trial detention and has been in prison for over 10 months. José Rubén’s son, who I spoke to before the closure of his father's newspaper, points out that these attacks have a very high cost for journalists in terms of time and finances.

“[The authorities] started with this whole series of lawsuits,” says Zamora. “They were originally civil lawsuits. The goal is always to attack the finances of journalists because they have to be paying lawyers and going to hearings. For the last 10 years, they tried to flood journalists with spurious lawsuits that made no sense.”

Journalists in other countries in the region have been subjected to similar fates. In April 2022, a judge in Nicaragua sentenced Juan Lorenzo Holmann, publisher of the daily newspaper La Prensa, to nine years in prison for money laundering in addition to ordering the newspaper’s facilities to be closed. He has since been released, expelled from Nicaragua and stripped of his citizenship.

Nicaragua: a taste of the future?

The repression against press freedom is starker in Nicaragua than in neighbouring countries. But other leaders in Central America are implementing similar tactics to put journalists under pressure and silence the press. Ortega has systematically both imprisoned journalists and forced them into exile. It has also made it very difficult for anyone to speak to the press.

“This double-sided criminalisation of both freedom of the press and freedom of expression with the purpose of silencing journalists, news sources and freedom of opinion represents the latest stage in a long process of demolishing the rule of law in Nicaragua,” exiled Nicaraguan journalist Carlos F. Chamorro recently said in our annual Reuters Memorial Lecture.

Nicaragua has also enacted legislation that has then been used to undermine press freedom. In 2021 the regime adopted the Special Cybercrime Law which punishes with prison time, for example, those who spread “false or biassed information that causes alarm and terror amongst the population.”

A 2020 law for the regulation of foreign agents required any Nicaraguan citizen working for “governments, companies, foundations or foreign organisations” to register with the government, report monthly their income and spending, and provide prior notice of what the foreign funds will be spent on. This law, which has been adopted in different forms by other authoritarian countries, allowed Ortega’s regime to monitor the finances of independent news organisations supported by foreign benefactors.

A similar law is now being discussed in El Salvador but with another dangerous caveat: that it would levy a 40% tax on all those civil society organisations or media outlets that the government considers to be participating in politics or disrupting the order and stability of the country.

“This threat basically made the sustainability of the newspaper impossible,” El Faro’s Araúz says. “How are you going to operate with a tax like that? This was another reason that led us to accelerate our departure.”

A spurious use of a well-intentioned law

The use of legislation as a weapon against journalists has also been heavily implemented in Guatemala. “A couple of years ago, a very important law was passed to protect women who live with a violent or abusive partner,” says Zamora. “And what happened? Female politicians and congresswomen started to use that law to sue journalists, which is a legal aberration. It is a serious use of that law and it even affects people who use that law legitimately.”

In 2022, Guatemalan public official Dina Bosch Ochoa filed a criminal lawsuit against three journalists of elPeriódico for psychological violence against women under the Law Against Femicide. That filing came right after the newspaper reported that the Guatemalan Electoral Authority renewed Bosch Ochoa’s contract and covered her alleged links to a corruption case. The piece suggested that she was hired for the job because her mother is president of the Constitutional Court.

The US newspaper Los Angeles Times also documented seven other examples where Guatemalan courts have issued restraining orders against reporters under this law that seeks to protect women against violence.

Since the beginning of President Alejandro Giammattei's administration in Guatemala in 2020, more than 30 justice operators, lawyers, journalists and human rights activists have left the country due to alleged persecution against them. In the three years of Giammattei's presidency, there have been more than 350 attacks against journalists and their work, according to the Association of Journalists of Guatemala.

Zamora says these attacks are a political persecution. “The state is all-powerful. It creates a criminal case with invented facts or twists some real facts to tell a lie, and this allows politicians to capture journalists and put them in jail,” he says.

No respite in the region

El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua are not the only countries in the region where the press is under siege. Jennifer Ávila, the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Hondurean investigative outlet Contracorriente, is also working in a very challenging environment.

While the main threat to journalists in Honduras is physical violence, Ávila explains, those who work in the media have also been prevented from doing their work in different capacities. Getting access to government sources has become increasingly difficult, as well as getting accountability from public officials. “Ministers or the president or the authorities talk directly to the people,” she says. “They use their government channels and don’t face public scrutiny.”

Even countries like Costa Rica and Panama, considered the most stable in the region, are experiencing attacks against journalists. Following the playbook of many regional leaders, Costa Rican president Rodrigo Chaves has been hostile towards journalists referring to some of them as “political hitmen”, “rats”, “evil people who want to harm the country” and “feudal lords.”

“The independent press is now stigmatised,” Ávila says. “Journalists are presented as sellouts or people who want to destabilise the government. In other words, all these types of narratives used by Nayib Bukele, by Ortega and even by Costa Rica’s President are narratives that place a greater stigma on journalists.”

Panama has also seen an increase in legal attacks against journalists and news organisations. Lawyers of former President Ricardo Martinelli attempted to seize assets from two journalists as part of civil lawsuits filed against them. Since 2020, one of the country’s main newspapers, La Prensa, has been unable to access any of its funds.

The Panamanian judiciary seized the shares and bank accounts of the newspaper at the request of former president Ernesto Pérez Balladares, who years ago filed a lawsuit against the newspaper for publications on alleged acts of corruption and money laundering committed by him. The case is still open. Earlier this year, unions denounced the use of lawsuits as a mechanism to threaten freedom of expression, asking justice authorities to be aware of these increasing threats.

A similar playbook

Authoritarian leaders and elected politicians across the region are using a similar playbook to attack the press. “We have a government that greatly admires Ortega and Bukele,” says Ávila. “We are no longer talking about the Cold War times in which there was a left or right. Now ideology doesn’t matter. Everyone is aligned.”

While Honduras still has independent media outlets operating in the country unlike its neighbour Nicaragua, press guilds are aware of the tactics used in the region.

“There is very little confidence that this will improve,” Ávila says. “On the contrary, it could get worse. Civil society organisations are keeping a close eye on this here in Honduras so that it does not turn into Nicaragua or El Salvador.”

For Zamora, the situation in Guatemala is made more complex because the country presents itself as a formal democracy with elections and a theoretical division of powers. This allows the state to get away with human rights violations.

“There is this facade of democracy,” says Zamora. “Then the President and members of his cabinet come out and say that these journalists are criminals and that they are being prosecuted for being criminals and not for being journalists.”

At the time this article was published, Zamora’s father was on trial for the charges brought forward by the state. On the first day in court, Zamora Sr. told reporters he was a “political prisoner” and expected to be convicted because he had no confidence in the court.

In El Salvador, spirits are equally dire. While Araúz hopes that the media environment improves, there is a strong possibility that Bukele will remain in power. He has announced he will be running for reelection in 2024 despite the Salvadoran Constitution having at least six articles that prohibit his immediate reelection.

“El Faro will continue to defend itself even though we know that the accumulation of power in El Salvador cannot ensure the rule of law,” Araúz says.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time