How evidence can help us fight against COVID-19 misinformation

A Hindu watches a healthcare worker fill a syringe with a COVID-19 vaccine in Ahmedabad, India. REUTERS/Amit Dave

The below is adapted from a presentation at the BBC Trust in News Conference March 22-24, 2021.

We are in the middle of a complex information disorder where credible, trustworthy news and other kinds of information competes with various kinds of false and misleading material. This contributes to confusion and many other problems, and at worst poses the risk of physical harm or undermining the integrity of elections.

The public knows this. In our 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, across 40 markets globally, more than half of internet news users worry about whether news they come across online is real or fake.

When we ask them about what sources of false or misleading information they are most concerned about, by far the most common response is domestic politicians – people recognise that misinformation often comes from the top.

When we ask them about what platforms they are most concerned about false or misleading information from, by far the most common response is social media, especially Facebook – people recognise that platforms enable and incentivise the dissemination of all sorts of information, including misinformation.

What can research tell us about how we can fight back?

First, at its best, journalism really matters. There is a lot of concern that people can’t tell the difference between news and misinformation, that we live in a post-truth era, in an environment where lies always travel faster and farther than news reporting.

There are very real problems we need to understand and address, but also important evidence of how news stands out, provides signal amid the noise.

Take two key findings from the United States, which has had severe forms of information disorder and four years with plenty of misinformation coming from the top as well as several prominent hyper-partisan outlets both on cable TV and online generating tons of social media interaction.

On the volume of news versus misinformation, one team of researchers found that across offline and online media use, “news consumption [comprises] 14.2% of Americans’ daily media diets” whereas “fake news comprises only 0.15% of Americans’ daily media diet.” – with time spent with news outweighing fake news, highly biased, and hyper-partisan sites by a factor of almost 100.

Looking specifically at Twitter, which may give at least an indication of dynamics on far larger platforms such as Facebook and YouTube where it is harder for researchers to access data, another team found that “fake news accounted for nearly 6% of all news consumption, but it was heavily concentrated—only 1% of users were exposed to 80% of fake news, and 0.1% of users were responsible for sharing 80% of fake news.”

There are wider issues than “f*ke news” as narrowly defined in these studies, including dangerous narratives that aren’t necessarily tightly tied to discrete checkable claims or specific sites, networked propaganda from specific constellations of political actors and partisan media, and problematic information including various kinds of hyper-partisan material, harassment, and trolling - often targeted at women, ethnic minorities, and marginalised communities.

But these findings on the relatively limited scale and scope of “f*ke news” narrowly defined are in the same order of magnitude as other peer-reviewed research from different teams, including this study and this study.

This is good news for journalists, who may fear the broad public no longer recognise the difference between their work and misinformation. Most do.

It is good news for media executives, who may fear that news is losing the battle for attention to “f*ke news”. It clearly isn’t.

It is also good news for all of us as citizens, because years of research document that paying routine attention to professional journalism from independent news media is associated with being more informed about public affairs, more active in political processes, and more engaged in local communities – just as our research at the Reuters Institute have found that those who rely on news media for information about covid-19 are significantly more informed about the disease than others.

This does not mean we have no problems with misinformation. We do have very serious problems. To address them, we need to understand the scale and scope and identify more precisely the actors driving the problems and the platforms where they are most severe. We also need to see information disorder from the public’s perspective, and remember that most people are sceptical of information they come across online, especially on social media and other platforms.

It is true that there are specific groups who believe in and actively spread conspiracy theories and other false or misleading narratives including around vaccines, that ordinary users can play an ambiguous role and sometimes inadvertently share false or misleading content or even co-create disinformation, and that there are political partisans who amplify and sometimes believe misinformation that comes from prominent figures they like and support.

In the United States, for example, much misinformation is consumed and spread by older conservative white men who express high levels of racial resentment. (Remind you of anyone?) But that does not mean that the public at large is lost at sea. Suggesting that they are is factually wrong and frankly condescending.

Part of this is healthy scepticism. Part of it is about the more “generalized scepticism” (perhaps sometimes even excessive scepticism!) that people show towards news and media. Part of it is about the specific “trust gap” we have documented time and again between news media in general, and then specifically news and information seen on for example social media such as Facebook, messaging applications such as WhatsApp, or video-sharing sites such as YouTube.

As said, some of the wider information disorder problems we face cannot be reduced to a clear distinction between true and false, narrowly associated with specific fake news sites, and sadly also reflect that, as one team of researchers have argued, rather troublingly, that mainstream news media playing “a significant and important role in the dissemination of fake news”.

The problems we face are not limited to easily identified “bad actors” or foreign agents. They involve domestic politicians, home-grown groups, news media, and platform companies, and reflect the fact that some powerful actors and organised groups are actively weaponising news media’s avowed commitment to impartiality and platforms’ express desire to be seen as politically neutral, and are turning these positions into forms of false balance that risk in practice empowering those who are willing to seek to subvert them.

But looking more narrowly at interventions designed to contain identified false or misleading information, or potentially increase the prominence of news reporting, scientists are beginning to independently test their efficacy.

Examples include work documenting how, by and large, citizens heed factual information even when it challenges their ideological commitments, independent fact-checking, in addition to generally having a significantly positive overall influence on the accuracy of political beliefs can also increase the reputational costs or risks of spreading misinformation for political elites, that nudging people to think about accuracy can reduce sharing of false claims, that correcting posts that include misinformation can significantly reduce misperceptions, and that relatively simple media literacy interventions can significantly improve discernment between mainstream and false news headlines.

None of these findings on their own provide “The Solution” to “The Problem”, because information disorder is not one problem with one solution - but all of them provide important evidence of things that can make a difference for the better.

However, the vast majority of these studies have been focused on the United States, despite the fact that we know that countries differ, both in terms of their political system, their media system, patterns of media use and public attitudes to politics and media. We cannot simply assume that interventions that work in one country will necessarily work, or work similarly, in other countries, where information disorder problems often have at least partially different, distinct dynamics.

To begin to expand our international basis of evidence on interventions that might work in different countries and different contexts, a team of us at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism has worked with funding from the BBC World Service to conduct research in Brazil, India, and the UK.

The research involved a series of online experiments conducted with respondents in each of the three countries, with control groups and treatment groups. Each experiment in each country involved a sample of about 1,000 respondents, representative of the population that uses the internet, for a total of about 9,000 respondents. In the UK and Brazil the sample had quotas for age, gender, region and income. In India, the research was limited to English-speaking respondents, and had quotas for age, gender and region.

This is work in progress, and full results from these pre-registered studies will be published after peer review, but here are a few preliminary findings from two of the online experiments we have conducted.

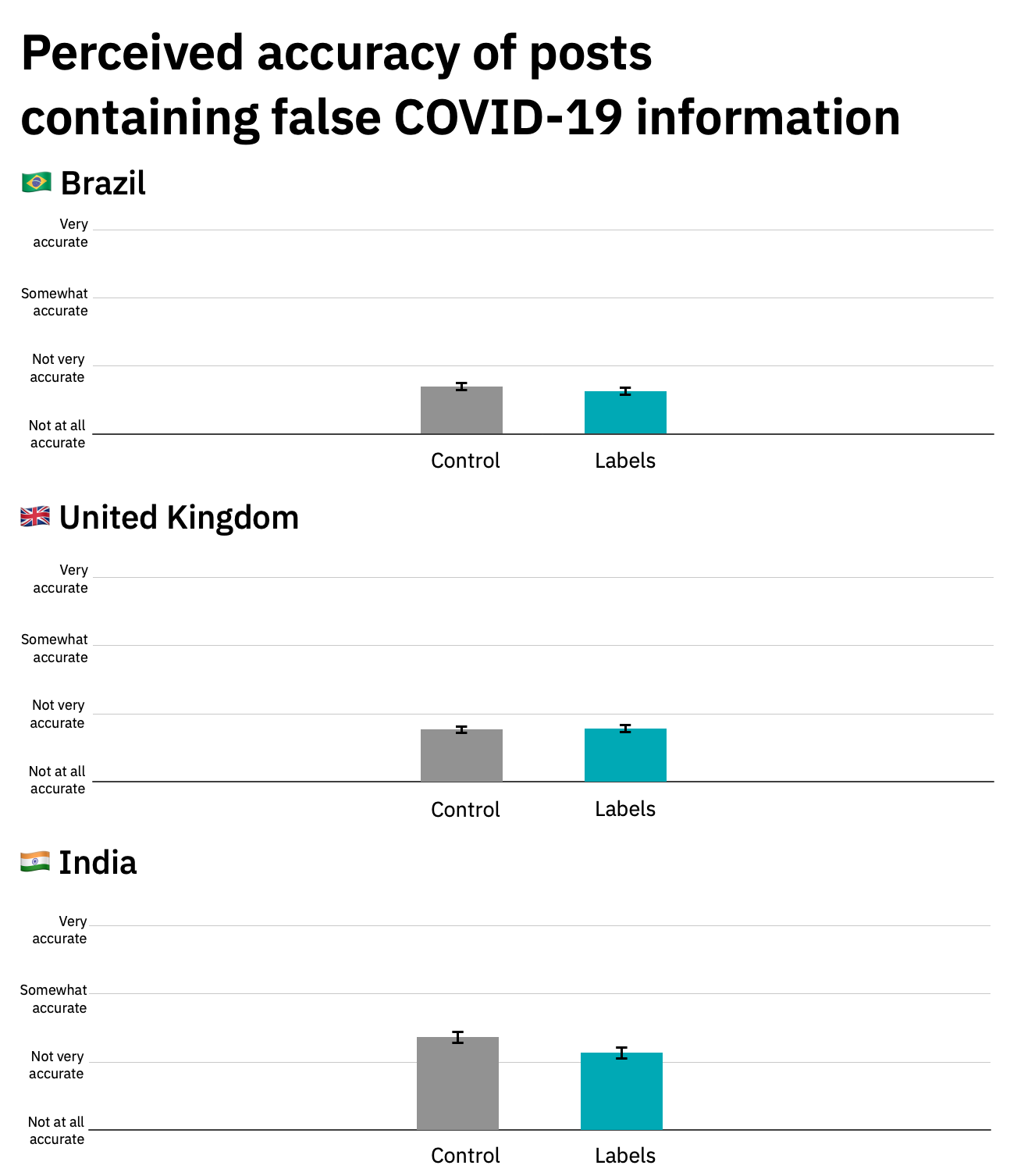

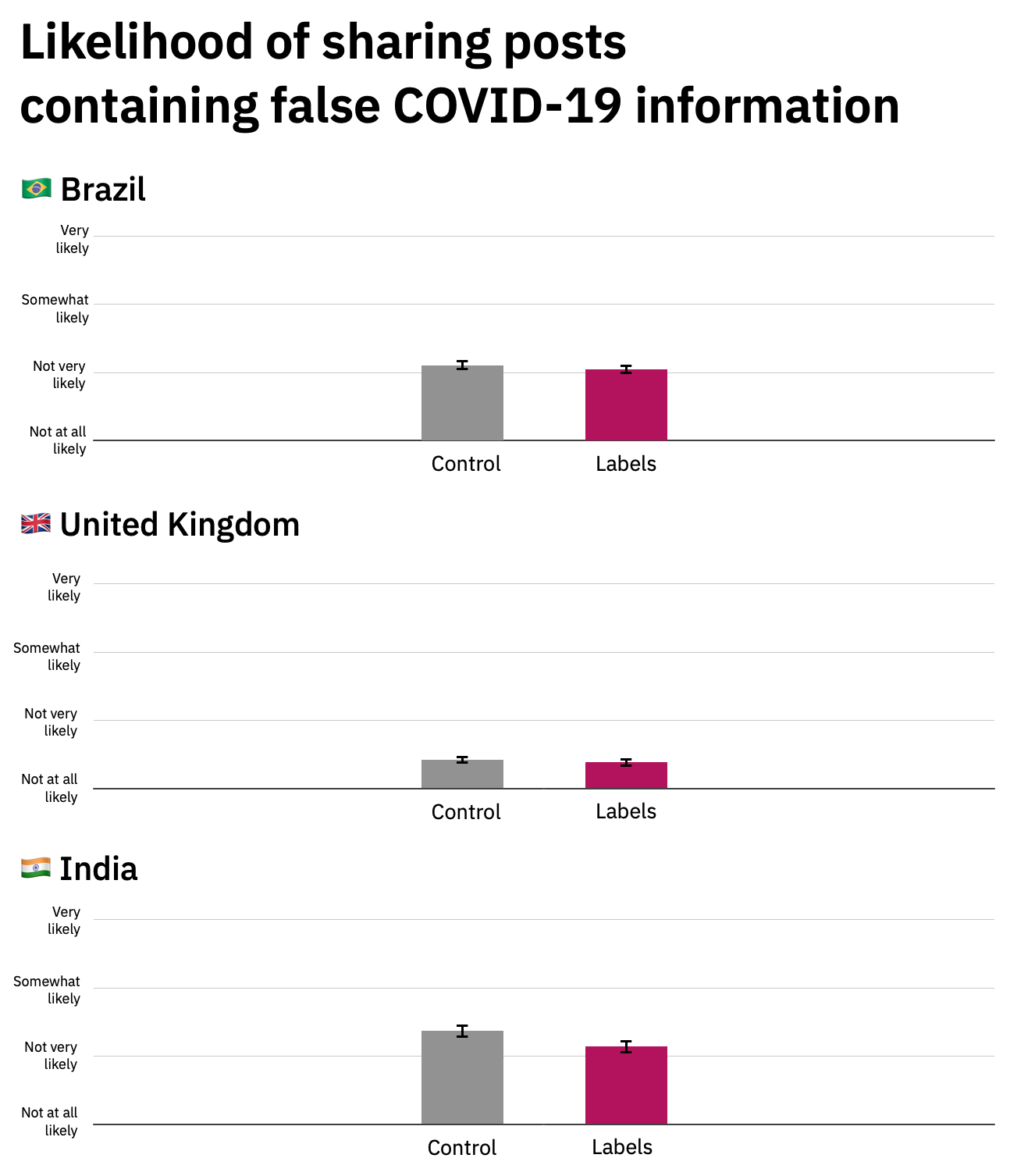

In the first set of experiments, we wanted to know if attaching “false” or “partly false” labels lead people to see COVID-19 social media posts identified as false or misleading by independent fact-checkers as less accurate (as one study from the US has found), and whether such labels influence their propensity to share such items.

Our preliminary analysis (see figures below) suggests that respondents generally rate false or misleading posts included in the experiments as not at all accurate or not very accurate, and the experiments show that attaching labels warning against “false information” or “partly false information” based on the work of independent fact-checkers can in some cases significantly reduce the already low perceived accuracy of these posts.

Furthermore, preliminary analysis also shows such labels can also significantly reduce people’s propensity to share the false or misleading COVID-19 posts (figures below).

In this experiment, our preliminary analysis shows statistically significant results in India, similar to what has been found in previous research in the US. The results in Brazil and the UK were not statistically significant. This underlines the importance of testing interventions in different markets, as their effect may vary.

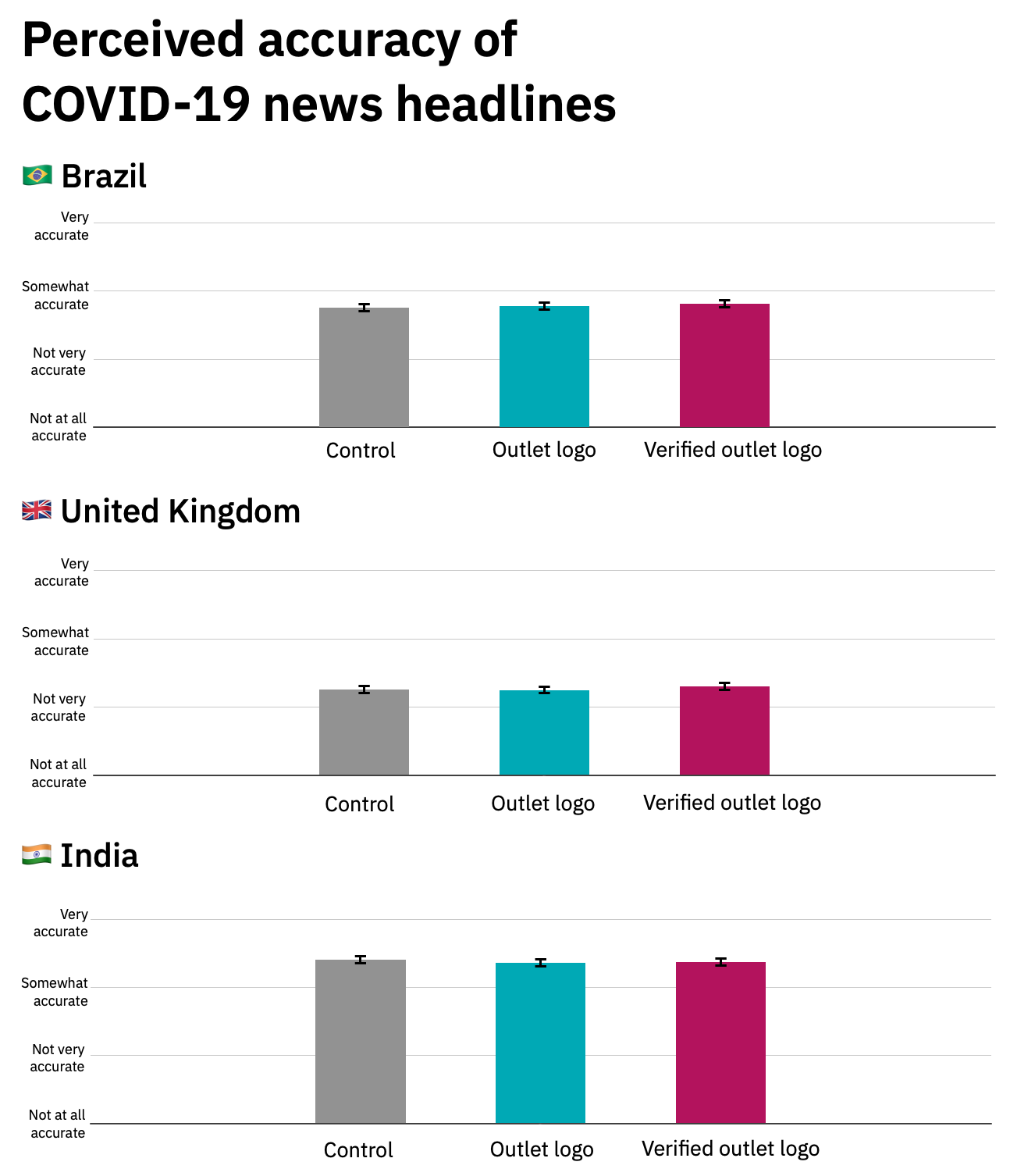

In the second set of experiments, we look at how people engage with COVID-19 news on social media, and how providing additional context (brand logos, verification) might influence the perceived accuracy of stories, based on similar research carried out in the US. Brand logos provide important cues to media users, remind them that the content in question is from, say, BBC, O Globo or the Indian Express, not just any random site on the internet.

Our preliminary analysis (see figures below) shows that people generally rate COVID-19 news items included in the experiments as relatively accurate, suggesting most people still have a clear sense of the difference between news reporting and false or misleading information. The experiments also show that adding additional context (a visible news brand logo, URL, or a news brand logo with a blue “verified” check) does not significantly further increase the perceived accuracy of news items.

This result is similar across all three countries, and similar to results from previous research in the US. Brands clearly matter greatly in many ways for how people access, engage with, and think about news, but not always in the ways we might imagine.

These experiments will provide an important basis of independent, evidence-based analysis on some possible interventions meant to counter misinformation and help people navigate information on social media. Statistically significant findings provide support for the efficacy of interventions. The absence of statistically significant evidence, whether around labels or brand logos, is not in itself evidence of the absence of effectiveness, and interventions can have other important effects than effects on end users (which is what we focus on here), but does suggest that some effects may only be meaningful at much bigger scale than our experiments (which of course applies to the biggest platforms), and suggest the need for further analysis to independently assess their impact.

Research like the work I’ve cited above (and more like it) as well as the work-in-progress we are doing in Brazil, India, and the UK with funding from the BBC World Service can help us better understand the precise scale and scope of the information disorder problems we face. Researchers find again and again that much misinformation, especially the most consequential misinformation, often comes from the top, is spread across platforms, in asymmetric ways with some politicians and partisan media playing an outsized role, and that the consumption and sharing of it is often heavily concentrated in specific communities.

News media are not new to the fact that some powerful people lie and mislead, or that some people buy into conspiracy theories and falsehoods, and actively try to spread them. But it is ever more urgent they find ways of responding to this to avoid amplifying misinformation.

Similarly, platforms have to decide how to deal with the frequently highly political, very asymmetrical, and often concentrated nature of many misinformation problems. Will they stand up to Presidents and other powerful actors if they lie and mislead the public, attack the integrity of elections, or spread potentially harmful health misinformation, the way some news media have sometimes done?

Tactical interventions like labelling false and misleading posts or providing more context on news stories won’t solve these bigger, more political, problems, but research suggests that some of them can make a demonstrable, significant difference, though they don’t always work equally well, or the same way, in every country. This underlines the importance of drawing on actual evidence when we seek to counter and contain misinformation. If we stick to doing things that feel good or look good, the risk is we do nothing to actually improve the situation.

And beyond focusing on the very real problems we have with identifiable false and misleading information, especially on platforms, we should also remember that people still engage with far more news than “f*ke news”, and that journalism can help keep people more informed and build resilience to misinformation, especially if it manages to reach a broad audience beyond the most engaged and privileged people that many news media are better at serving than they are less privileged, more diverse, and historically marginalised communities.