How billionaires and powerful law firms are working to restrict libel protections and silence the press in Trump’s America

A man carries a 'Fake News' T-shirt at a campaign rally in Orlando, Florida in June 2019. REUTERS/Carlo Allegri

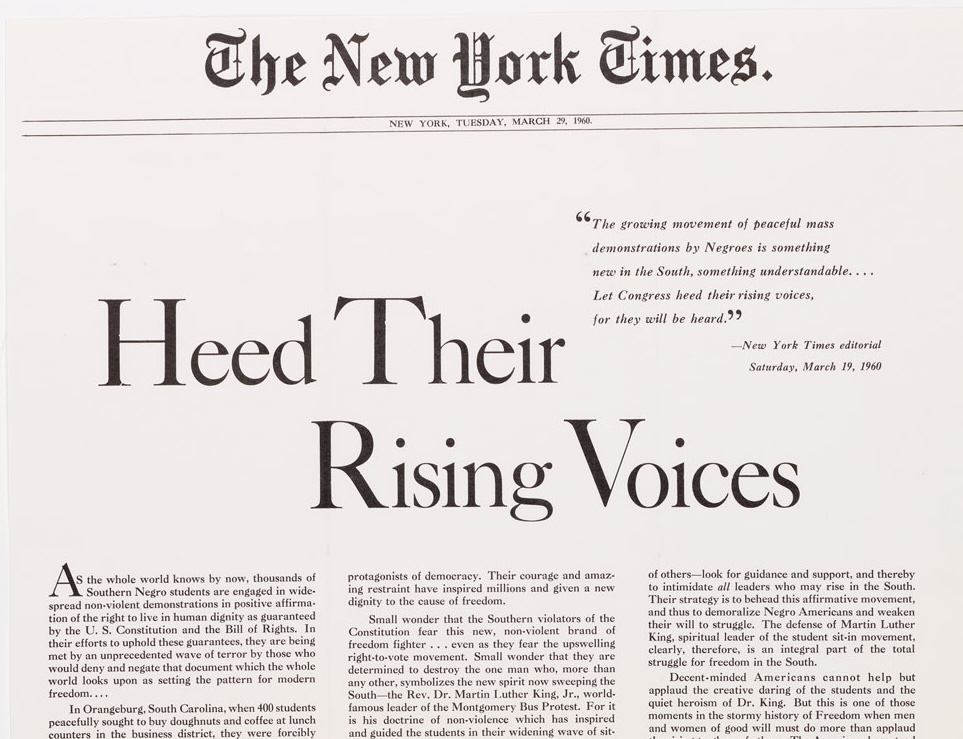

It all started with a one-page ad in the New York Times. It was paid by a group of civil rights activists and published on 29 March 1960 under the title Heed Their Rising Voices to steer support towards Martin Luther King Jr.

The gist of the advertisement was true, but it contained several factual inaccuracies. For example, Dr King had been arrested four times, not seven as the text said. The police hadn’t been called to the Alabama State College campus, they only deployed near it. Student protestors hadn’t been padlocked inside a dining hall “in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

Although the Times only sold 394 copies in Alabama at the time, local journalists spotted the ad and wrote about it. This brought the issue to the attention of Montgomery’s city commissioner, L. B. Sullivan, who filed a libel lawsuit against the Times. Other Southern public officials followed, seeking $3 million in damages, which is around $31 million today.

After losing the case in local courts where some of the jury members showed up in Confederate costumes, the newspaper's lawyers appealed to the Supreme Court arguing that the verdict made it so dangerous “to criticise official conduct that it abridges the freedom of the press.”

In March 1964, the Court announced a unanimous decision in the case New York Times vs. Sullivan. This decision would become a legal precedent protecting journalists from libel prosecution by public officials. Lawsuits could only succeed if they proved that any statements were “made with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard” for the truth.

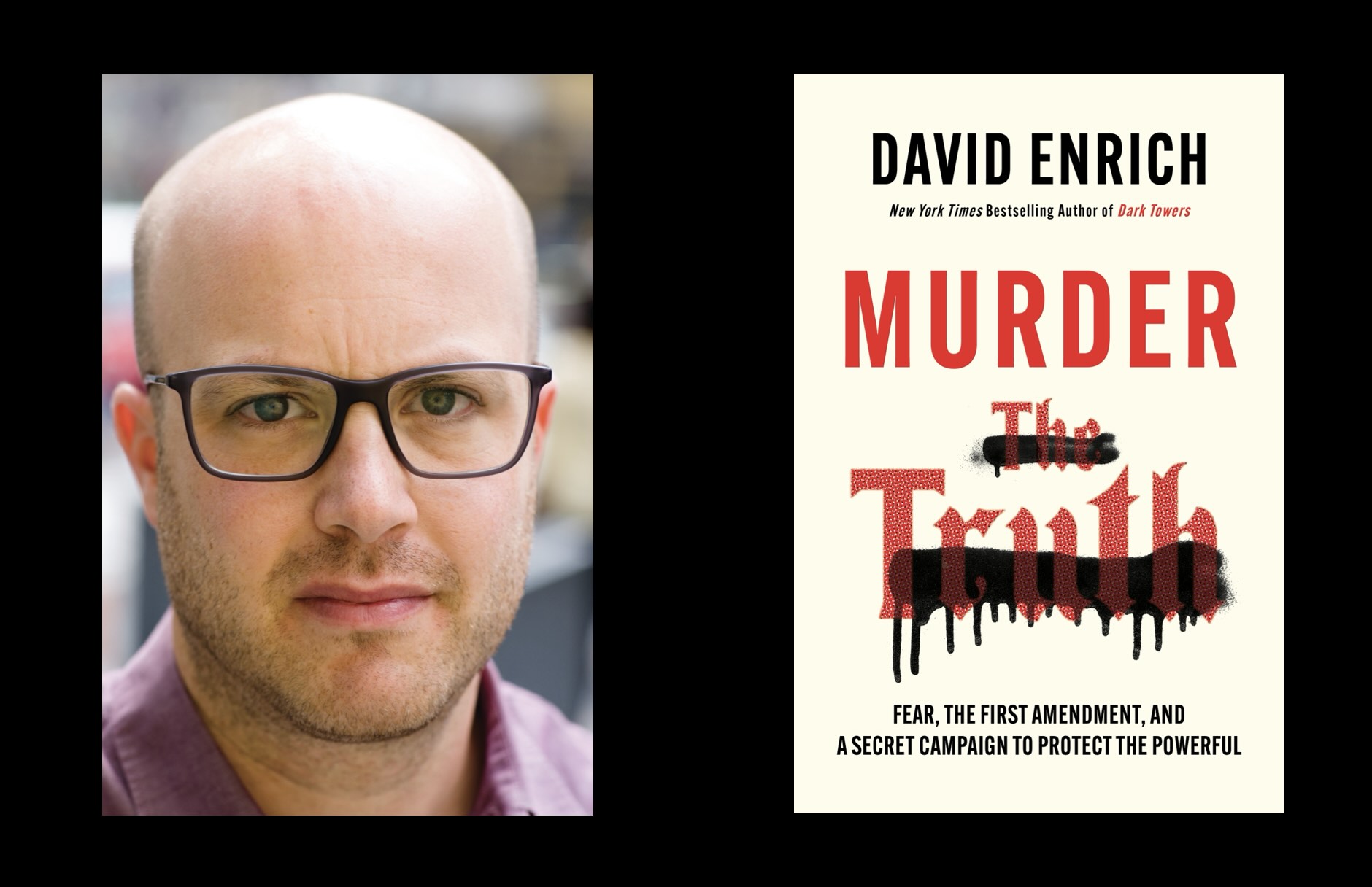

The Court later expanded the protections afforded by New York Times vs Sullivan to protect against libel cases by any public figures, and helped create a framework under which public interest journalism flourished. This framework is now under attack, according to a new book by New York Times investigations editor David Enrich.

Murder the Truth is an exposé of the right-wing campaign to overturn this important precedent to muzzle the media and silence dissent. I recently spoke to Enrich about this campaign against press freedom, how it affects independent journalists and small publications, and why it might be turbocharged under Donald Trump.

1. Why ‘New York Times vs Sullivan’ matters

It’s important to keep in mind how American journalists operated before Sullivan. Before 1964, it was easy for any public figure to sue the news media if they accidentally got a fact wrong. Powerful industrialists like Henry Ford or James Fisk fought any negative coverage with ruinous lawsuits. With Sullivan’s lawsuit still pending and fearing a wave of litigation, even the Times barred its journalists from reporting in Alabama and urged them not to write about the state’s institutional racism.

The Sullivan decision upended the status quo and made it much more difficult for any public figure to win a libel case. “The test is what’s known as the ‘actual malice standard’,” Enrich said. “This means that the only way that a public figure can prevail in a defamation case is if they can prove that the journalist either knew that what they were publishing was false or acted with reckless disregard for its accuracy.”

The Court aimed to encourage vigorous debate. There is no way to do that if every time someone speaks or writes about a powerful person, they have the threat of ruinous litigation hanging over their head.

This standard was later extended and came to apply to businesspeople, major companies and even to borderline public figures, such as an air traffic controller who is on duty when a plane crashes.

“This air traffic controller is certainly not seeking out the spotlight,” Enrich said. “But under the way the Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment, journalists have the right to get some facts wrong about them as long as they are operating essentially in good faith. That might seem unfair to the air traffic controller, but the idea is that it's important for them to be able to look at matters of public interest without having to censor themselves.”

The Sullivan decision crucially shifted the burden of proof from the defendant onto the plaintiff. What a journalist writes is assumed to be true, and it’s up to the plaintiff to prove otherwise. “Investigative journalists tend to operate in good faith,” Enrich said. “Sometimes we get things wrong, and we are mortified, but it’s not for lack of trying.”

The model is very different in places like Britain, where it’s much easier to silence journalists through the legal system and where the burden of proof is reversed: when sued, journalists have to prove that what they wrote was true. This is the world before Sullivan and the one envisioned by those who want to overturn it.

“I’m an American journalist, and so I'm doubly biased,” Enrich said. “As a journalist, I believe in the free flow of information. As an American, I cherish the First Amendment, which has created a very different media climate in the US that is much more robust and hard-nosed.”

2. Why ‘Sullivan’ is now under threat

The protections of New York Times vs Sullivan have been widely accepted across the political spectrum. As recently as 2010, far-right Republican Senator Jeff Sessions celebrated the unanimous passing of the so-called SPEECH Act, a piece of legislation that made foreign libel judgments unenforceable in US courts, unless any foreign legislation applied offers at least as much protection as the First Amendment.

This environment started to shift in the spring of 2016. The first salvo was the case that brought down Gawker, a news site with a reputation for breaking news about celebrities and pushing the envelope. Unhappy about being outed as gay by the outlet, billionaire Peter Thiel secretly funded a lawsuit by professional wrestler Hulk Hogan against the site.

Hogan sued Gawker for invasion of privacy after it published a tape of him having sex with a friend’s wife. A jury awarded $140 million to Hogan. A later settlement reduced this sum to $31 million, but this was still too costly for Gawker, which filed for bankruptcy and was sold to Univision in June 2016.

“The Gawker case established a roadmap for billionaires to destroy news outlets that they didn’t like,” Enrich told me. “Thiel had an army of lawyers searching for any avenue by which they could attack Gawker. The Hulk Hogan case was very strong, but regardless of its merits, it established very clearly that a well financed campaign targeted against an individual news outlet can be effective.”

The timing mattered too. A couple of weeks later, Trump, already the frontrunner in the Republican primaries, called for opening up the American libel laws. The lawsuit which brought down Gawker was not a libel suit and was very different from the usual libel lawsuits from powerful people. But Trump was impressed and publicly marvelled at the Gawker verdict at a meeting with the Washington Post editorial team.

“He was almost awestruck,” Enrich said. “The case sent a clear message to other billionaires: that there was a roadmap for taking down a news organisation. Trump’s recognition in real time that this type of lawsuit could be weaponised explains a lot.”

There was another important connection between Trump and the Gawker case. In May 2016 Trump picked up an important new backer: Peter Thiel, who had been flirting with right-wing extremism for a long time. Thiel explained privately that part of his reason for betting on Trump was what he’d learnt from the surveys they’d commissioned in Florida before the Gawker trial. These surveys showed strong feelings against the news media and an electorate who despised coastal elites.

3. The law firms involved

A few months after the Gawker verdict, Rolling Stone was found guilty in a defamation case over a flawed article, now debunked and retracted, about gang rape in the University of Virginia. The firm representing the key plaintiff in the case was Clare Lock, a company that presents itself as the leading defamation law firm in the US.

Soon after this legal victory, Libby Lock, who founded the firm with her colleague Tom Clare, started to speak up about libel laws. As a member of the right-wing Federalist Society, she was frequently featured at legal conferences and often appeared on Fox News.

“Lock used her public profile to campaign aggressively for the overturning of New York Times vs Sullivan and to advance the argument that the current interpretation of libel laws was so onerous on plaintiffs that they couldn’t possibly prevail in court,” Enrich said. “The great irony was that the reason why she had this megaphone was that she had just won a case which completely contradicted this argument.”

This didn’t stop other high-profile experts from pushing for overturning (or at least restricting) Sullivan. Not everyone on the right agreed.

A few months before he launched his failed bid for the Republican presidential nomination, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis announced a bill designed to provoke a Supreme Court reckoning over this case. The legislation, presented by DeSantis at an event with Lock and others, failed when conservative radio stations lobbied aggressively against it.

The lawyers behind these cases are quite open about being inspired by Trump. They saw his tactics and thought this made juries willing to consider cases that, not long ago, would have been lost

Around the same time, Fox News agreed to pay Dominion Voting Systems nearly $800 million to avoid a defamation trial that would have exposed how the conservative network promoted lies about the 2020 presidential election.

“The case showed that this is not a black and white issue,” Enrich said. “A couple of things happened as a result. On the one hand, the case helped build a little bit of support for Sullivan on the right as Newsmax and others were also being sued. On the other hand, some voices on the left complained about Sullivan as a stupid precedent that protects people who lie.”

Enrich doesn’t think this issue cuts cleanly across partisan lines: “There are people who are for free speech and others who are more interested in ridding the world of anything that might resemble misinformation, and are willing to constrain the media in the process. I don't think there's a very good way to bridge that gap.”

4. How Trump is fanning the flames

Why is the mood now shifting among Republicans? “The simplest answer is Donald Trump,” Enrich said. “A lot of the lawyers behind these cases are quite open about being inspired by Trump. They saw his tactics and the way he was selling distrust towards the media and thought this made juries much more interested and willing to consider cases that, not long ago, would have been thrown out of court or would have been lost.”

Trump’s frequent lawsuits against news organisations, his threats at reporters, his recent statements saying that critical news outlets should be illegal, and his campaign’s decisions to ban journalists from covering events have created an atmosphere that benefits powerful people suing the media.

“If those cases now stand a chance,” Enrich said,” it’s partly because Trump remade the federal judiciary in his own image by nominating judges at the Supreme Court and lower courts. His rise also created a very clear signal that this was an effective strategy, which is now trickling down from the national to the local level.”

All around the country, conservative lawyers and activists are pursuing claims that seem far-fetched at first glance, but end up being quite effective. Even if they lose, they drag journalists through years of very expensive litigation.

Enrich’s book details how this tidal wave of litigation has muzzled independent journalists, small magazines and local reporters around the country.

There’s the case of Sheereen Siewert, the editor of a small newspaper in Wisconsin, who’s spent thousands of dollars in litigation after publishing that a powerful businessman had slurred a teenager during a community meeting. “Every time I write a major story today, I have to think twice about the risk I’m taking,” Siewer says in the book.

Small publications are often the most vulnerable. Idaho billionaire Frank Vandersloot sued Mother Jones top editor Monika Bauerlein for calling him antigay in one of their pieces. The magazine corrected some significant errors in the article, but rejected this request and litigation dragged on for about two years.

When a judge threw out the lawsuit on Sullivan grounds in 2015, Mother Jones had spent $600,000 to cover its legal bills. When it came time for the magazine to renew its libel insurance, 40 out of 42 insurers refused to even offer a quote. Ultimately, they found an insurer, but their premiums more than doubled to $75,000, the amount of coverage dropped by a third, and their deductible soared to $150,000. Right after the verdict, Vandersloot announced the creation of a fund to finance lawsuits against the media.

“We are used to dealing with these letters at places like the New York Times, but it’s ruinous for smaller publishers,” Enrich said. “One of the good things about today’s media environment is the rise of these people doing newsletters or podcasts or just being independent journalists. But they are so vulnerable to these legal threats. They are operating on a financial knife’s edge and they can’t afford to hire expensive lawyers or to pay for libel insurance. So this campaign takes a severe toll on them.”

5. Will ‘Sullivan’ fall?

The campaign against Sullivan has gathered pace in the past few years. In February 2019 Clarence Thomas, seen as the leading conservative justice in the Supreme Court, changed his mind and supported overturning Sullivan in a surprising opinion outlining his thinking on the matter. Thomas argued that libel should be a matter of state law and that the Court should find an appropriate case with which to reconsider what he views as a wrong precedent.

Prominent conservative voices saluted Thomas’ opinion. Two years later, another conservative justice came out in support for overturning Sullivan in an opinion about a case brought by the son of an Albanian former prime minister against a journalist who published a book about him.

Neil Gorsuch, nominated by Trump during his first term in office, argued that Sullivan should be restricted on the grounds that today’s media landscape is very different from the one in 1964. Gorsuch borrowed this argument from an obscure academic article by David Logan, a legal scholar from a small university in Rhode Island.

The article included several inaccuracies that seeped into Gorsuch’s opinion. For example, Logan’s article quoted a report from the Media Law Resource Center that claimed that only one in ten jury awards survived on appeal between 2010 and 2017. But this didn’t mean the rest was overturned: eight of those 21 cases were settled before any appeal, four were never appealed at all, and the appeals in three other cases were pending at the time the report was published. That left only six cases in which higher courts had ruled on damages. In four of those cases, appeals courts had modified the damages awarded by jurors. In the other two, the damages had been affirmed.

It’s easy to take the ‘Sullivan’ world for granted. I’m not predicting it will change, but it definitely might, and there certainly are a lot of powerful people who are hoping it will

The real ratio was one in three (not one in ten) and it was based on a very small sample, which made it misleading and dubious as a legal argument. After an attorney pointed this out to the Supreme Court’s public information officer, justice Gorsuch, quietly and retroactively, took this out from his dissent.

Powerful law firms and conservative activists are now actively gunning for Sullivan, with several cases aiming to reach the Supreme Court, including lawsuits by Sarah Palin and billionaire and Trump donor Steve Wynn.

Enrich doesn’t know where every member of the Supreme Court sits on this issue right now. Those against Sullivan need at least two more votes beyond Thomas and Gorsuch to accept one of these cases, and three more votes to overturn the current precedent.

“In the short term a more likely scenario is that the Supreme Court agrees to take a case that seeks to narrow the kind of public figures who have to meet the higher standards imposed under Sullivan,” Enrich said. “The air traffic controller we discussed earlier would be a good candidate. This might sound innocuous, but would be a very big deal because it would protect secretive Russian oligarchs or local real estate companies. These people deserve public scrutiny too.”

6. Why Trump 2.0 matters

Enrich filed his book before the 2024 US presidential election. But it’s tempting to read it as a warning about some of the ways in which the current president can silence the press. ABC News has recently paid $15 million to settle a weak lawsuit Trump filed against the network. Paramount, the company behind CBS, is reportedly exploring to do the same. Other news organisations are either caving to him or not fighting Trump’s most arbitrary decisions.

Will Trump turbocharge the campaign against Sullivan? Enrich thinks he will. “Trump himself has an outstanding defamation case against CNN,” he said. “So there is definitely a scenario in which Trump himself, or at least Trump's lawyers, file a petition with the US Supreme Court seeking to overturn Sullivan, and one of the things we’ve seen with the Supreme Court in recent years is that certain justices have shown a surprising deference to the President.”

From the vantage point of the Oval Office, Trump continues to file or threaten to file lawsuits against news publishers for news stories he doesn’t like. Enrich sees this as a dangerous precedent. “It sends a powerful message in a country that prides itself on its free press,” he said. “Most media lawyers I’ve talked to see this as something designed to curb the press, which is something that really runs counter to our traditions.”

Does Enrich think that the First Amendment has given American journalists a false sense of security? “I’m not sure, but we have benefited from having journalists who are not constantly terrified of getting sued,” he said. “We screw up all the time. We get facts wrong. We emphasise the wrong stories. But we operate in good faith and we provide an extremely valuable service to the public.”

The Sullivan precedent was decided 15 years before Enrich was born. He’s always operated within that framework, but he’s imagining a much darker world. “Sullivan enables us to do that job much better than we otherwise would be able to. It’s easy to take this world for granted. I’m not predicting it will change, but it definitely might, and there certainly are a lot of powerful people who are hoping it will.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time