On the cusp of abundance? How AI may redefine our relationship with news

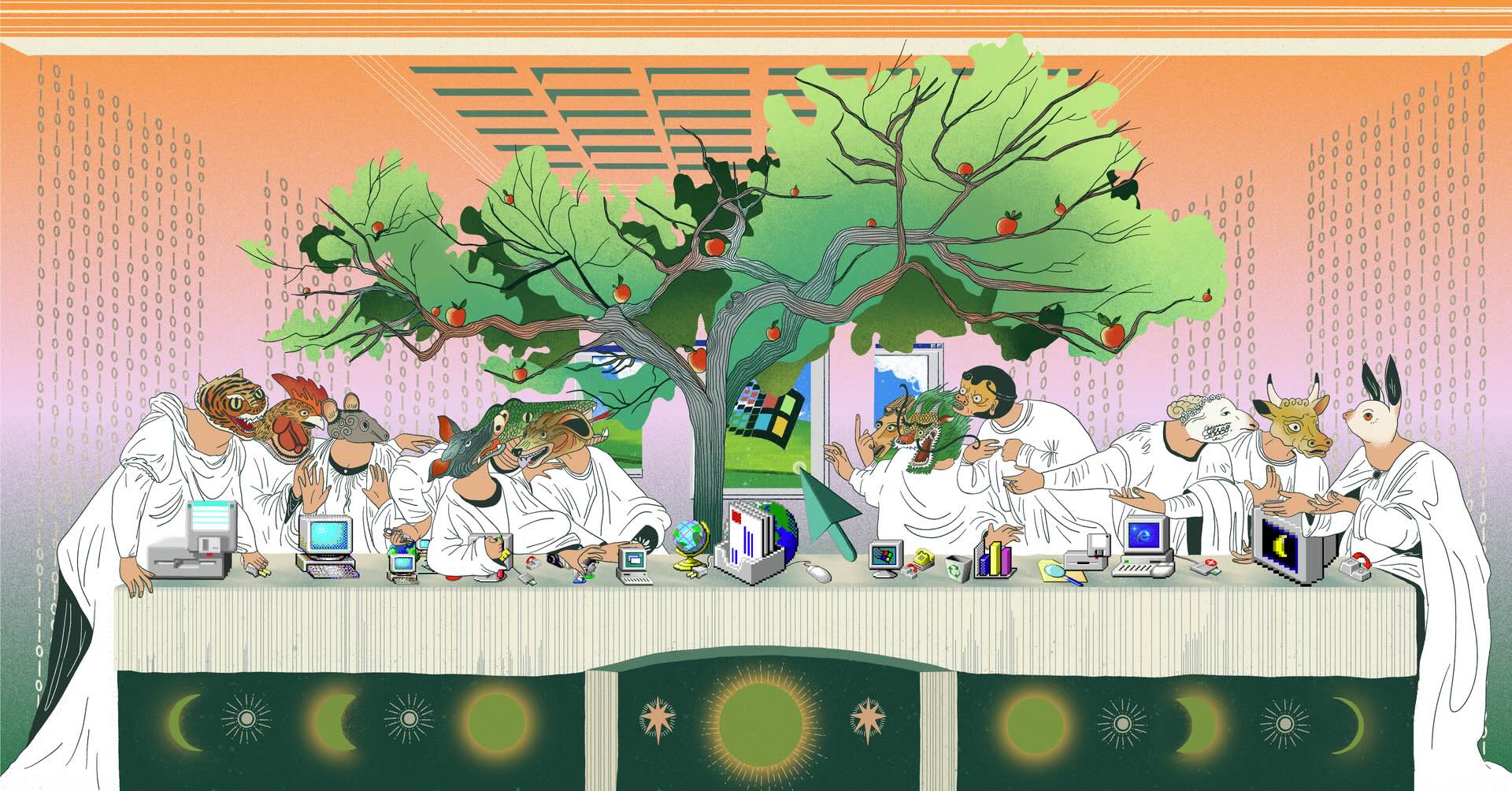

Jamillah Knowles & Digit / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This essay is an extract from a much longer and more detailed discussion published by David Caswell on the Radically Informed Substack, as part of a series titled An AI Enlightenment?

We are often told that AI will utterly transform our lives and societies in the coming years. This disruption will be particularly intense, it is claimed, in knowledge-producing sectors like academia, publishing and journalism. This isn’t just idle speculation, or the pronouncement of experts, but also the common conclusion of most people who engage significantly with AI interfaces like ChatGPT.

When you have personally experienced a Large Language Model (LLM) reading, writing and speaking, articulately and fluently, with encyclopedic knowledge and careful reasoning, then it is quite natural to assume that societal functions based on those skills will be transformed beyond recognition.

But transformed into what?

What would a society whose information flows were fully mediated by AI look like? More specifically, what would the experience of living in such a society be like? How would it differ from today’s familiar media experiences? What would we know? How would it feel?

Imagining a different future

We don’t know, of course, but it is interesting to observe how difficult it is to even speculate about radically different models of news and societal information. Science fiction has been notoriously uninventive when it comes to journalism, and we lack an array of imagined possibilities commensurate with the flying cars, limitless fusion energy, starships and humanoid robots that drive investment in the physical world.

We don’t get to see how the Heptapod aliens of the movie ‘Arrival’ do journalism on their home planet, or how the employees of Starfleet Command receive their news in the San Francisco of the 23rd century.

Perhaps news and informational narratives are just too close to us, too deeply embedded in our minds and lives, for us to easily imagine how they might be fundamentally different. Perhaps deeper and broader demand for journalism is somehow constrained by the limitations of its supply.

The speculation about possible futures for journalism that we see most frequently from the news industry and from academia tends to be both vague and pessimistic – a dystopian world of ubiquitous AI-generated misinformation marked by widespread ignorance, riven by conspiracy-driven passions and filled with conflict actively stoked by authoritarians and eagerly exploited by greedy corporations and their AI accomplices. A just deserts, perhaps, for a world that has displaced traditional journalism from its ‘rightful position’ and turned its back on the sober guidance of important editors.

This is a vision of the future of journalism that is oriented primarily by the past – a vision for which the true ideal, the desired North Star, is The Way Things Used To Be. Furthermore, this is a vision that is subtly but significantly influenced by the role of journalists and editors in that future.

This vision privileges the importance of journalists in the information ecosystem over the wants and needs of citizens, customers and societies – a warning about the awful consequences of embracing alternatives to the status quo. It is also, in my opinion, deeply infused with paternalistic assumptions about the ability of people to accurately value and effectively consume societal information in ways that benefit them – assumptions that are generally not well-supported by evidence.

Lastly, it is a vision that is inherently unactionable, even futile, because it fights against the largest tides of culture, business and technology.

What this essay is for

In this essay I will try to imagine a positive future for news in a world of ubiquitous AI. I will try to be relentlessly ‘user-centric’, prioritizing individual consumers in their lives over the situation of information producers. I will aim to de-centre the past and orient instead towards the ideal of a well-informed and high-functioning society in which AI-enabled access to information is an engine that drives individual wellbeing and expands the common good.

I will be optimistic not only because I choose to position myself on the AI Vanguard, but more importantly because optimism permits agency in a future that is still unwritten.

Finally, I will try to be specific, in the hope that specificity can encourage practical advancement towards positive outcomes, as well as inviting useful criticism and proposals of alternatives.

This essay is the first of a fourth-part series:

- In a second essay I will examine investment in a positive vision of AI-mediated journalistic information, making the case that fully embracing the potential of AI can plausibly convert ‘news’ from a damaged sector in terminal decline into a thriving sector exhibiting explosive growth and justifying tech-like investment and valuations.

- In a third essay I will review specific opportunities for significant investment in the emerging AI-mediated information ecosystem, focusing particularly on ‘line-of-sight’ from existing and likely near-term AI capabilities to the broad diffusion of AI-mediated information throughout society.

- A fourth essay will focus specifically on culture as both a constraint and increasingly as an accelerant towards a positive vision of an AI-mediated information ecosystem, including at the level of teams, organisations and especially of societies.

These four essays together are intended to form a sort of manifesto for an abundance agenda for news. My primary objective is to inspire ambition. I am trying to make the case that in the long span of human history the application of journalistic information to the cause of a better society is a journey that has barely begun. AI is the next, and perhaps greatest, step on that journey.

How far have we come?

Imagine that you live in Europe in 1425 – perhaps as a peasant on a farm or as a shopkeeper in a small town. Now imagine how much you know about your world. You probably know much about your immediate surroundings, about the activities of your neighbours and about the daily and seasonal patterns of nature.

You might learn something from time to time about what is happening in your region from passing travellers, or during your infrequent visits to a market town. You are probably sometimes required to listen to information from monarchs or nobles, delivered by their soldiers, or from popes and bishops, delivered by their priests. And that is probably all that you know.

Your ignorance about the world beyond what you personally experience would be almost total. Not only do you not know, but you don’t even know that you don’t know. Your ignorance, and that of your fellow citizens, is likely also reflected in the quality of your life and of your society. It would probably not be a life or society in which a person from 2025 would voluntarily choose to live.

A person in 2025 knows far more about their world than a person in 1425. From the moment we wake in the morning until the moment we fall asleep at night we are saturated with journalistic information. We consume information from a bewildering array of devices, alerts, apps, websites, social media feeds, video platforms and podcasts and, for a few, from printed newspapers, magazines and broadcast news programmes.

We hear that the Pope has died 30 minutes after his death. We read about a new study suggesting that red wine is bad for your health. We watch prime ministers and presidents respond to questions posed to them about contentious issues just a few hours ago. We get a feel for a day in the life of a soldier in a grinding war on the other side of the continent. We know what Billy Eilish said about Taylor Swift at a party in Santa Monica yesterday evening.

We know that an ongoing heatwave in Pakistan is unprecedented in recorded history and is most probably caused by changes in our climate. We hear about a court case in America that has blocked new tariffs from coming into effect. We know that a member of our local council has called for an external audit of a street revitalisation project. We know what experts have recently said about affordable housing, or about the prospects for the economy, or about the best washing machine to buy, or about a quick and easy recipe for baked salmon. We know that a football team in Italy is winning a match that began just 30 minutes ago, and that a tennis player in Australia feels confident about a qualifying match she will play in a few weeks.

Here in 2025, we know inconceivably more about what is happening in our world than a person in 1425. Even those of us who are uninterested in news, or who actively avoid news, are steeped in knowledge about events and society that sometimes seems to seep into our minds through digital osmosis.

This explosion of journalistic knowledge has improved our lives to a degree that would be utterly unimaginable to a person of 1425. It enables us to grow as aware and engaged individuals. It provides us with opportunities, choices and control over our lives. It fosters participation, collaboration and accountability. It enables democracy, human rights and the rule of law, as well as markets, contracts and trade. It lets us feel informed. It has, directly and indirectly, played an enormous role in delivering us comforts and security unprecedented in human history, including the banishment of hunger, and the doubling of our lifespans. Most people would eagerly choose to live a modest life in 2025 over even the most privileged life of 1425.

How have we come this far?

This truly dramatic improvement in our ‘journalistic knowledge’ was driven, obviously, by innovation. Humanity, collectively, figured out: how to print information on paper at scale; how to organise the production of accurate information using the scientific method, journalism and similar truth-seeking processes; how to communicate centralised information using postal services, radio and television; and how to share distributed information using the internet and social media.

We have come a very long way since 1425, but we still share a very important characteristic about journalistic knowledge with the people of that time: we still don’t know what we don’t know.

Why would we believe that this centuries-long journey towards more and more knowledge about our world and society has somehow reached its full conclusion? Why would we believe that we no longer have enormous opportunities to improve our lives and our societies by better informing ourselves? What evidence do we have that the current level of activity and service in journalism and news production just happens to be at some kind of end state, beyond which there is nothing more to do? And why would we think this at the dawn of the era of AI and quite possibly of AGI or even ‘superintelligence’?

We have clearly not reached any kind of ‘end of history’ in journalism, and so we should take the prospect of radically expanding our access to journalistic knowledge in the AI era very seriously. To understand what such an expansion might look like, let’s first consider the extreme limits of manual journalism, from an idealised consumer perspective.

Life as a billionaire news junkie

Imagine you are a news junkie. You really like to know what’s going on. You subscribe to three national or global news sources, plus a local news source. You spend several hours each day reading news on your phone, or on your laptop. You have a list of magazine sites, specialty publications and Substacks that you visit often. You are informed and knowledgeable – the kind of person that journalists often think of as their audience and that journalists often are themselves. You genuinely enjoy consuming news.

Now, imagine that you win several billion US dollars in a lottery, even though you don’t remember buying a ticket. Your first step in your new life as a billionaire is to hire a chief-of-staff, who quickly assembles a ‘family office’ of highly skilled professionals focused on financial management, philanthropy and legal services. None of this excites you, however, and so you cast about for some way to deploy your new resources on some meaningful pursuit. And then it hits you – you will create a personal newsroom, working just for you.

Working with your chief-of-staff and some expensive consultants, you begin. You first hire a small team of reporters, whose job it is to dig deeply into topics and stories that interest you.

One reporter is tasked with spending all day on X, Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and LinkedIn, searching out stories that match your interests. Another focuses on government departments whose portfolios interest you, reading their reports, listening to speeches from their ministers and analysing their data. A third spends their time focused on the small town where you grew up, keeping tabs on local gossip, activities and events in ways that help you maintain a connection with your past. A fourth acts as a sort of roving investigator, assigned opportunistically to whatever interests you that day. A fifth and sixth support the others by helping with tasks like fact-checking, interviewing, research and writing.

Everyone needs an editor

The new team works hard, and your life improves noticeably. You know more of what you want to know, when you want to know it! But after a while you begin to feel a little overwhelmed. You tire of coming up with stories for your reporters to explore, you are made uneasy by the angles and tone of some of your reporters, and you don’t have time to read all the PDFs and email bulletins that they send you each day. You consult with your chief-of-staff and arrive at a solution – hire some editors!

First you hire a personal assignment editor, tasked with maintaining an awareness of your whims, interests, needs and wants, and then passing that on to the reporting team in the form of story assignments. Next you hire a curation editor, tasked with sifting through all the stories that the reporters produce, and prioritising which ones you see according to your mood and available time, and a managing editor to oversee the operation of your newsroom.

Finally, you hire an editor-in-chief, tasked primarily with ensuring that the news produced by your newsroom is always accurate, well-verified and trustworthy. After some initial familiarisation, your new editors begin to understand you and to ‘get’ what you look for in news, and the quality of the news bulletins you receive improves significantly.

Now you’re really excited! You huddle with your chief-of-staff and your editors and brainstorm about what to do next. The result is an ambitious plan, which your team begins to execute immediately. You hire some political reporters, tasked with preparing you for the upcoming elections and informing you of your political donations. You hire some health reporters, who dig into news relating to your various ailments and suggest actions you might take.

Soon a nutritionist and a food reporter join the team, working with your personal chef to make sure you’re fully informed about your diet and culinary opportunities. A pair of local reporters join next, keeping you up to date on issues relating to construction permits for your new mansion and initiatives to keep your city clean and safe.

You hire some culture reporters, tasked to continually find and review concerts, exhibitions, plays, books, lectures and courses that match your interests and that would help you to grow your cultural capital. You add a community reporter who keeps up on what your friends and neighbours are doing, and some technology reporters who can advise you on new apps, devices and innovations. You add an education reporter, tasked with bringing you the knowledge you need to give your kids, and yourself, the best education possible.

Next comes a small science team, a space reporter, a business desk and a trio of economics reporters who examine your investments and inform you about risks and opportunities. By now you’ve also had to hire more editors to prioritize and process all the information that your growing newsroom is producing.

You continue on. An environmental team, a wellness and lifestyle team, a personal meteorologist and an eccentric old lady who generates horoscopes just for you. You hire foreign correspondents and you place them in countries and cities where you vacation or have a business interest. You hire some biographers, who research the backgrounds of public people you are interested in. You hire an ethics reporter, who reaches out to philosophers and religious figures with your questions and moral challenges. Finally you hire some retired football players and some golf journalists to keep you up to date with what’s happening in your favourite sports.

By now you have around 200 reporters and editors working just for you, plus dozens of freelancers who do on-the-ground reporting as needed and a highly skilled team of script writers, illustrators, audio producers and video producers who turn your reports and bulletins into enjoyable experiences better suited to your morning gym sessions or your late nights in front of the TV.

After several months of feedback, your assignment editor and your curation editor develop a deep appreciation for your tastes and demands. Every person in your newsroom is highly motivated, works long hours and follows instructions carefully, but is also creative, resourceful, thoughtful and deeply loyal to you. Each of them is devoted to providing you with complete information about your life and world, according to your stated wishes, and to directly supporting your day-to-day wellbeing, your civic responsibilities and your long-term personal growth. You begin to feel at ease with your newly enhanced awareness of your world. You learn how to use it and improve it. You feel almost omniscient.

Information abundance for everyone?

It's relatively easy to imagine a future scenario in which a well-orchestrated system of interacting AI agents delivers an experience of news similar to this to hundreds of millions of people simultaneously. By stretching the experience of manually-produced news ‘to the limit’ we have gained some sense of what the scaled automation of news gathering and news production might lead to.

We all might soon have our own personal newsrooms. But this is grossly insufficient.

The application of AI to journalism offers far more than merely the automation, and thus democratisation, of the news experiences of a billionaire, a prime minister or a president. AI gives us capabilities that are simply not available from any newsroom staffed by humans – regardless of size or budget.

This essay is an extract from a much longer and more detailed discussion published by David Caswell on the Radically Informed Substack, as part of a series titled An AI Enlightenment?

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time