In this piece

A new vocabulary for journalism’s growing problem with expertise

Clockwise from left: Joe Rogan, Dave Smith and Douglas Murray recording Joe Rogan Experience #2303 on 10 April 2025. Credit: Screengrab/YouTube

In early 2025, a dispute about the value of expertise spilled out from the gravitational centre of the podcast universe: The Joe Rogan Experience. A long-time “safe space” for comedians, creators, and contrarians to riff unchallenged on everything from martial arts to geopolitics, Rogan’s show has become one of the most influential media platforms in the world, and a recurring flashpoint in debates about misinformation, free speech, and trust.

On 10 April, those tensions surfaced openly when one of Rogan’s guests challenged him directly. The conservative commentator Douglas Murray questioned Rogan’s habit of inviting people who had “appointed themselves experts” to speak authoritatively on complex matters such as war, history, and public policy. Why platform voices without clear qualifications on issues with serious consequences?

The exchange quickly escalated. Another guest accused Murray of elitism and being “anti-democratic in spirit”. Should only credentialed experts be allowed to speak? Hadn’t outsiders sometimes been right during the pandemic, when established authorities were wrong? And what, exactly, counted as expertise in the first place?

The conversation collapsed into familiar accusations: elitism versus populism, censorship versus openness, experts versus “ordinary people”. What was largely missing was a shared language for explaining why certain claims should carry more weight than others, how disciplinary boundaries matter, or when disagreement is epistemically legitimate rather than distorting.

A journalistic problem

It may be tempting for journalists to regard this clash with a sense of superiority, or even vindication. Yet the Rogan episode dramatises tensions that journalism itself confronts every day. Whether writing a quick quote story or investigating a complex technical issue, journalists must constantly decide whose knowledge is relevant, how much authority to grant it, and how to present it responsibly to the public.

As the media scholar Zvi Reich observes, journalism plays a central role in shaping public understanding of expertise: as gatekeeper, curator, and legitimiser of expert knowledge. Yet we are often surprisingly unclear, even to ourselves, about the standards and judgements we apply when doing so. This should give us pause. It is staggering how much of the criticism directed at the press in the digital era centres around perceptions of biased or activist expert sources, and around journalism as either serving elite interests or elevating fake or misplaced expertise.

This project aims to illuminate journalism’s growing difficulties with expertise from both theoretical and practical perspectives. Drawing on a range of approaches – from political philosophy and media studies to exemplary science journalism – it aims to situate the problem in a broader democratic context and begins to connect these considerations to how we can navigate expertise more wisely in everyday journalism.

Doing better could be essential not only to preserve trust in journalism but for that trust to be warranted.

For those who do not have time to read the full project, I offer two prospective shortcuts: a summary of the problem, and a glossary of helpful language.

Morten Mørland’s cartoon, titled “Michael Gove Experts!”, appeared in The Times on 20 April 2020. Reposted with permission.

If the COVID-19 pandemic taught us anything, it is that expertise matters for democracy because modern democratic decision-making depends on specialised knowledge. We rely on experts to understand risks, trade-offs, and likely consequences in areas ranging from public health to taxation.

At the same time, the pandemic effectively reminded us that science is inherently incomplete and open to revision in light of new evidence.

Political decisions rarely rest on fully settled science, and uncertainty breeds disagreement. As a result, decisions that affect people’s lives often involve value judgements about evidence thresholds, acceptable risk, uncertainty, and social priorities. Many are judgements that no expert community can legitimately resolve in isolation from the public.

This is where journalism comes in – and where the problems this project seeks to unpack begin. Journalism’s difficulties with expertise are connected to democratic tensions created by the power experts are granted in modern societies. The report draws on political theory in an attempt to shed light on what this could imply for understanding journalism’s role – especially in a digital era where the public recognition of expertise is shifting. As one philosopher put it: expert authority is now “at the same time frighteningly powerful and fatally weakened”.

Journalists have a responsibility not to mislead and to protect audiences from disinformation and deception. This means elevating the best available knowledge – and it means holding the (presumed) experts to account. The scholar Michael Schudson reminds us that journalists should also see it as a scandal whenever political actors try to silence or distort the message of independent experts.

And it must all be done while fulfilling another core journalistic mission: sustaining a societal conversation that includes diverse perspectives and disciplines and that gives the public a meaningful voice. This creates a tension that needs to be better understood.

But expertise also poses a tangible practical challenge to journalists: a central claim of some of the experts consulted for this project is that journalism’s difficulties stem from their epistemic position. Journalists are structurally epistemically inferior to the experts they cover: they usually cannot assess technical claims directly but must instead make second-order judgements about credibility, relevance, and authority. In practice, this often means relying – more or less self-consciously – on rules of thumb (heuristics) for who to trust. Journalists draw on cues such as credentials, adherence to scientific consensus, conflicts of interest, and performance in debate deciding which expert claims deserve attention and how they should be framed. (See Glossary tab.) Applying such criteria is however difficult. As the philosopher Alfred Moore emphasised in an interview: “The dismal answer is there are no shortcuts.”

Journalists are faced with a paradox, Moore contended: on the one hand, it would be “epistemic overstepping” if journalists try to pick winners in expert debates. But at the same time, we can’t allow ourselves to be manipulated or to risk passing on harmful misinformation unwittingly. “You then can’t get away from the need to exercise some substantive judgement about the quality of the sources,” Moore said.

“You’re going to make selections. You’re going to decide who to talk to, who to foreground, and how to characterise the positions in the debate. And you can’t be neutral in those judgements. You will be acting as a meta expert, no matter what you do.”

While insufficient, the different criteria for trust may nevertheless provide a language for pitfalls and opportunities journalists encounter when navigating specialised knowledge. Discussing their strengths and limitations can sharpen journalists’ critical thinking and awareness of their own limits when facing technical analysis and disagreement between scientists.

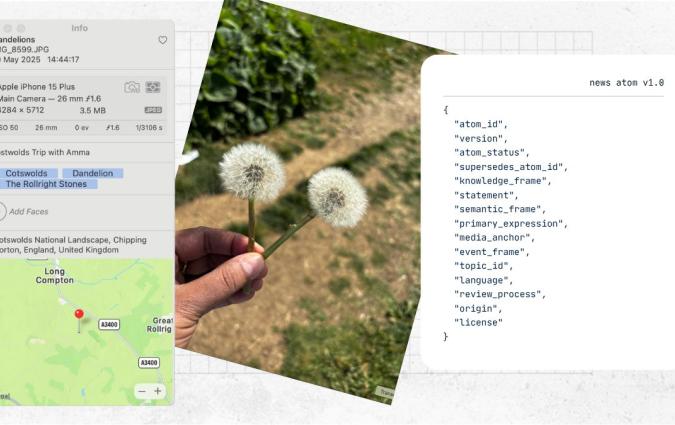

To further clarify this “meta-expertise”, the project draws on the Periodic Table of Expertise, developed by Harry Collins and Robert Evans. It provides a map of different kinds of expertise that is also relevant to journalism. The framework helps explain why some voices are appropriately authoritative in certain contexts but not others, and why confusion about expertise often arises when boundaries are crossed or left implicit. (See Glossary tab.)

This framework also highlights the importance investing time in conversations with scientists and other experts. A lot of what matters, such as who is taken seriously within a field, exists as tacit social knowledge within expert communities. If journalists are to avoid getting lost in deciding what to read and who to rely on when navigating a complex domain, they must make use of their unique access to such informal judgements. The opportunity to speak to multiple top experts with diverse perspectives is the journalist’s most valuable asset in overcoming their relative ignorance.

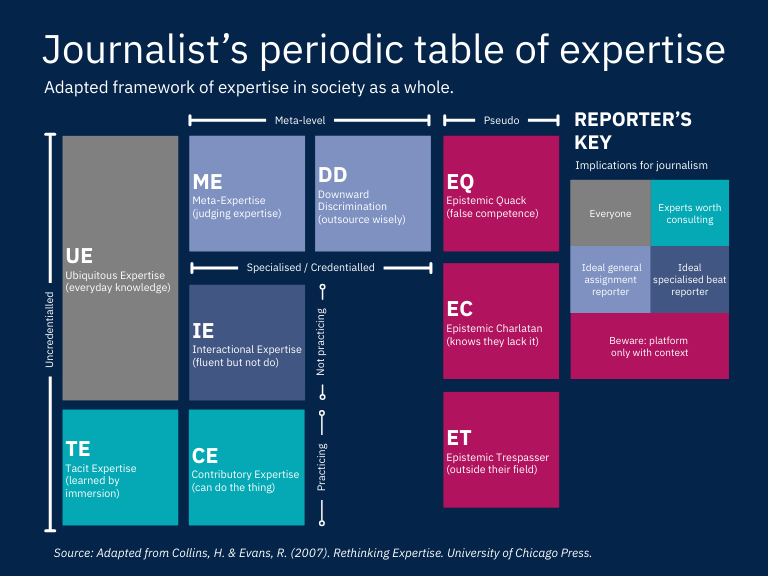

Importantly, the project also introduces the journalist and philosopher Vanessa Schipani’s work on trust in science, particularly her Responsiveness Model.

Schipani challenges the assumption that consensus is always the appropriate basis for public trust, especially in policy-relevant contexts. But when science is summoned for policy decisions, it is uncertain and contested more often than not. The expectation that scientific advice should be objective (that is near certain and value free) then provides fertile ground for distrust and discrediting accusations of bias. Schipani, however, argues that trust in policy-relevant science can be warranted even in the absence of a robust consensus, provided that scientific advice is epistemically responsive to evidence and alternatives, and – crucially – also responsive to public values. For journalism, this shifts the focus from policing perceived agreement to explaining science as a process and demanding responsiveness from scientific experts – both to the evidence and with regards to the value choices that guide their conclusions.

These arguments suggest that journalism’s democratic role is not to eliminate disagreement or defer unquestioningly to expertise, but to critically mediate between expert knowledge and public reasoning, especially at the intersection between science and policy. For a more in-depth explanation, download the PDF with the full project.

The full project (PDF here) does not offer prescriptions for how journalists should handle expert sources. Instead, it explores literature on judging expertise and the role of experts in democracy to better understand the challenge to journalism. One possible lesson is that journalism's troubles with experts are not only professional or ethical, but also conceptual: we seem to lack a shared language to discuss what kinds of judgements journalists are already making when using expert sources and for describing how journalism mediates between specialists, institutions, and audiences.

Developing such a vocabulary may help journalists name and discuss recurring dilemmas they encounter when dealing with expert disagreement, uncertainty, and power. This could make it easier for them to become more deliberate in their choices and may make it more likely that debates about trust, bias, and politicisation are clarifying rather than moralistic.

What follows are some examples of helpful terms discussed in the project that also hints at the complexity and scope of the problems at hand.

Judging expertise (without pretending to be experts)

- Epistemic inferiority. Journalists are structurally less knowledgeable than the experts they cover. Recognising this gap is not a failure but a starting point: it explains why journalism must rely on heuristics, institutional signals, and second-order judgement rather than direct evaluation of technical claims.

- Meta expertise. Expertise about expertise; the ability to judge who is qualified to speak, even without mastering the underlying domain. Much of journalistic work with experts is best understood as meta-expertise rather than failed contributory expertise.

- Downward discrimination. A strategy for managing epistemic limits by outsourcing judgement to those with greater relevant expertise. For example, asking one expert to assess the claims of another. Used well, it mitigates epistemic inferiority; used poorly, it can entrench elite consensus.

- Novice/2-expert problem. The predicament faced by non-experts when equally credentialled specialists disagree. Journalism encounters this problem constantly, yet rarely names it, leading to inconsistent handling of expert conflict.

- Heuristics of expertise. Practical rules of thumb – such as checking consensus, track records, conflicts of interest, or dialectical performance – that journalists use to assess credibility when direct verification is impossible.

Expertise, disagreement, and distortion

- False balance. Coverage that gives equal weight to opposing claims even when one is far better supported by evidence or expert judgement, often in the name of neutrality.

- Manufactured uncertainty. The strategic amplification of doubt to delay action or undermine confidence in well-supported findings.

- Manufactured consensus / manufactured controversy. Situations where apparent agreement or disagreement in public debate does not reflect the actual state of expert knowledge.

- Dialogical irrationality. The continued assertion of claims that have already been addressed or refuted, creating the appearance of ongoing debate where none exists.

- Dialectical superiority. A marker of credibility proposed by Goldman: when one expert can consistently respond to objections while another cannot.

Power, politics, and the authority of expertise

- Politicisation of expertise.The entanglement of expert authority with political advocacy. While often treated as corruption, politicisation must be distinguished from the unavoidable presence of values in policy-relevant science.

- Policy-relevant science. Research used to guide public decisions. Unlike settled science, it is typically uncertain, incomplete, and shaped by value judgements about risk, thresholds, and trade-offs.

- Value judgements. Non-deductive choices embedded in research and expert advice — for example, decisions about acceptable risk or evidentiary standards — that shape outcomes without being reducible to facts alone.

- Democratic responsiveness. The requirement that expert advice used in policymaking be open about how public values and trade-offs influence recommendations.

- Epistemic responsiveness. The willingness of scientists and experts to revise claims in light of new evidence, methods, or critique.

Journalism’s position between insiders and outsiders

- Interactional expertise. Fluency in a domain’s language sufficient to engage meaningfully with contributory experts, without being able to perform the work oneself. This is often the realistic target for specialist journalists.

- Outsider–insider balance. The tension between maintaining critical distance from expert communities while understanding them well enough to interpret claims accurately.

- Bipolar interactional expertise. Reich’s description of journalists’ dual skill: interacting expertly with sources while also translating and mediating knowledge for audiences.

- Mutual legitimation. The reinforcing dynamic in which experts gain authority by appearing in the media, while journalism bolsters its own authority by quoting experts.

- Credible knowers. Individuals recognised as trustworthy sources of knowledge – a status that journalism actively constructs through selection and framing, rather than merely discovering.

Expertise in democratic systems

- Fifth branch of government. Jasanoff’s term for science advisers and experts whose influence on policy is so extensive that they function like an informal extra branch of governance.

- Science-related populism. Political narratives that pit “ordinary people” against “scientific elites”, challenging not just specific claims but the legitimacy of expertise itself.

- The fact of expertise. The inescapable reality that modern governance depends on expert input, regardless of political attempts to deny or discredit it.

Why this language matters

These terms do not resolve journalism’s problems with expertise. But they make those problems visible, discussable, and contestable. Without a shared vocabulary, debates about trust, bias, or politicisation collapse into moral accusation or institutional defensiveness. With one, journalists can better explain why they trust certain experts, how they handle disagreement, and where judgement is being exercised.

Conclusion

Expertise matters for democracy not because experts should govern, but because contemporary democratic decision-making depends on specialised knowledge. However, democratic legitimacy cannot be grounded on expert claims alone. Policy decisions involve normative judgements about risk, trade-offs, and priorities that no expert community can settle in isolation.

As journalists, we hold onto the ideal that better information leads to better decisions, but in practice expert advice and analysis is often uncertain, value-laden and contested. This creates a dilemma for journalism: we are expected to reinforce expert “consensus” in order to counter misinformation, while also sustaining debate and public challenge. When disagreement is suppressed, journalism appears deferential; when it is amplified without context, it appears distorting. Accusations of politicisation thrive in this gap.

This project does not provide solutions. What it does offer is a deeper understanding of the problem, and it presents frameworks and conceptual tools to help clarify the kinds of judgements journalists are already making when they select their expert sources, interrogate them, and frame what they have to say. This points to the value of a shared language for making journalism’s epistemic judgements visible, contestable, and defensible. Trust in journalism may depend on how these judgements are exercised and explained.

More than ever, democracy needs good journalism at the intersection of science and policy. But getting expertise right is difficult and time-consuming. It requires attention from editors and newsroom managers, as well as recognition of the accumulated expertise journalists themselves develop over time.