In this piece

Listening to what trust in news means to users: qualitative evidence from four countries

A shoe shiner reads a newspaper after the election of Jair Bolsonaro as new Brazilian President, in Sao Paulo, Brazil October 29, 2018. REUTERS/Nacho Doce

In this piece

1. Introduction↑ | 2. Trust as a shorthand for familiarity, reputation, and likeability↑ | 3. Attention to journalism practices, but limited knowledge about it ↑ | 4. An elusive pursuit of balance and impartiality↑ | 5. The role of the platforms↑ | 6. Conclusion ↑ | References ↑ | Appendix↑ | Footnotes | About the Authors ↑ | Acknowledgements ↑DOI: 10.60625/risj-xhyg-0e19

1. Introduction ↑

How do people view media they come across in everyday life, and what can that tell us about why they do (and do not) trust the news they encounter? In early 2021, the Reuters Institute held a series of focus group discussions and interviews with cross-sections of people on four continents to learn more about the way people think about these matters. They told us about what they liked, what they disliked, and, most importantly, what they found trustworthy and untrustworthy about news, and why.

This report summarises several of the insights we took away from these conversations. What we learnt speaks directly to previous research on trust in news – which we detail in a previous report (Toff et al. 2020) – but in other ways these discussions raise some uncomfortable questions about the nature of trust in contemporary digital media environments. In short, we find that trust often revolves around ill-defined impressions of brand identities and is rarely rooted in details concerning news organisations’ reporting practices or editorial standards – qualities that journalists often emphasise about their work.

While some audiences hold clear notions about what certain brands stand for and how to think about the work they produce, we also find consistently that many do not – a pattern which repeats itself across countries, media environments, and even levels of trust in news in general. Instead, audiences draw on shortcuts shaped by past experience in some cases, partisan or social influences in other cases, as well as contextual factors involving social media, search engines, and messaging apps, which are increasingly central to how people find and engage with news worldwide (Newman et al. 2020).

1.1. Background

This report is part of a larger Reuters Institute project that aims to study why trust in news is eroding in many places around the world, what it means to different groups in different contexts, what its implications may be, and what organisations that deem themselves deserving might do to restore it.

We focus on media environments in four countries – Brazil, India, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US) – each not only differing greatly in their cultures, politics, and media systems but also resembling each other in how centrally important digital platforms have become as critical information brokers. This change in particular has generated growing concerns about what role such companies may play in how people stay informed and engage in civic life. Trust in the sources of information people encounter both on and offline may or may not be affected by these profound changes, but existing scholarship has often been limited to single country studies and/or single methodological approaches, and so our up-to-date understanding of trust in news across countries and across platforms remains limited.

Our goal with the larger project is both to broaden and deepen efforts to study trust in news by collecting data in more places and conducting research using a mix of complementary methods. In this report, we take a largely inductive approach using qualitative data, a ‘method of listening’ (Cramer 2016), which we describe below.

1.2. How this report was constructed

This report draws on open-ended conversations with 132 individuals in all four countries, a technique that allows for probing how people make sense of complex, polysemic, and sometimes abstract constructs. Although we are unable to make statistical generalisations about how all people in a given country think about news using this approach, we are better able to grasp the context around how people form their views and why.

Working with the research organisation YouGov, we recruited adults in the four countries, selecting a mix of people who were both more and less trusting of news in general.1 We also screened study participants to capture a variety of other characteristics including age, partisanship, and forms of media use. Our approach involved a combination of focus group discussions and in-depth interviews (see Table 1), with all interactions occurring over the internet due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Each of the 90-minute focus group discussions (18 – 21 January 2021) was administered by YouGov using a chat-based platform similar to common messaging services. We used insights from these eight focus groups to inform additional one-on-one interviews with separately recruited individuals using an online video conferencing platform (25 January – 17 February 2021). These interviews were conducted by the Reuters Institute research team.

Table 1

Given technology and other factors involved in recruitment, we specifically focused on people on the higher end of the socio-economic spectrum in each country: those with access to reliable internet service, most typically residing in major metro areas, and with average or above-average education. These are, in effect, people who generally have the most advantaged access to information in their respective countries. In previous studies (e.g. Tsfati and Ariely 2014), socio-economic differences have often been linked to how frequently people consume news and what forms they use, but there are mixed results with respect to any relationship with trust in news. In future studies, we hope to expand our focus to other less advantaged groups using additional research methods and approaches.

Most focus group discussions and interviews were conducted in English, except those in Brazil (Portuguese) and a small portion of the interviews in India (Hindi). All were recorded, transcribed, and translated to English, and analysed by the research team for commonalities and differences in an iterative and inductive manner. In the report, we focus on several of the core themes identified through this process, including illustrative examples from the transcripts where possible. In most cases, we focus mainly on similarities observed across the four countries as these were often most striking, but throughout the report we weave in some key differences as well. Where we include quotes, we identify study participants using pseudonyms.

Finally, although we recruited focus group participants and interviewees according to a screener survey question that divided people into more trusting and less trusting groups, it was often difficult to distinguish between those belonging to one group or the other except in extreme cases. Most people held a mix of overlapping, nuanced views about the variety of news media they encountered in daily life. We report how study participants responded to the screener question in the appendix, but otherwise we rarely refer back to this classification scheme.

1.3. Key findings

Despite considerable differences in the media environments in each country, our focus group discussions and interviews revealed a great deal of common ground between people in how they thought about and articulated concerns about trust and the news media in their respective countries.

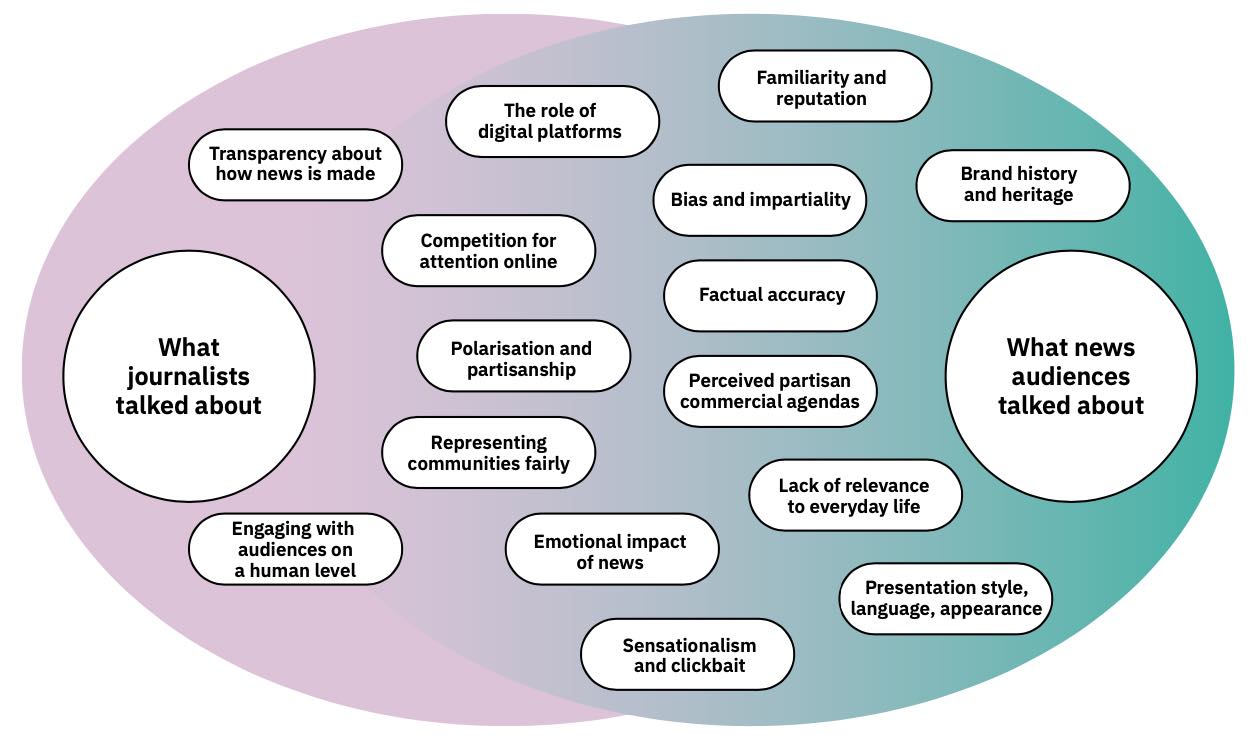

In Figure 1 (overleaf), we summarise the main topics we heard expressed in these exchanges alongside several of the things we heard most frequently from journalists in our previous interviews (Toff et al. 2020). Although there were some areas of overlap between the two groups, news audiences were far more likely to emphasise their sense of familiarity with brands or stylistic qualities pertaining to appearance or how news was presented. Most put far less emphasis on news organisations’ journalistic practices since only a few were particularly knowledgeable about how news was made or even interested in knowing more about such matters.

Figure 1. Summary of themes captured in discussions with journalists and news audiences

Note: ‘What news audiences talked about’ refers to themes covered in this report. ‘What journalists talked about’ refers to themes discussed in our previous report (Toff et al. 2020). While there were many areas of overlap, some themes were primarily discussed by one group or the other. Those themes are depicted furthest apart from each other on the left or the right.

We highlight several of this report’s key findings here:

- Familiarity with brands and their reputations offline often shaped how people thought about news content online as well. Across all four countries, when people described what led them to trust or distrust news organisations, many used the term as a kind of shorthand for news sources they were familiar with and their sense of a given brand’s reputation (good or bad). Conversations about trust would often lead to more general impressions about things people either liked or disliked about news media, which suggests the boundaries between a news source that is ‘trusted’ and a news source that is simply ‘likeable’ are often blurry. Brands can be cues for trust, but also for distrust. Both more trusting and less trusting individuals tended to articulate trust in this way.

- Editorial processes and practices of journalism were rarely central to how people thought about trust. Only a small number in each country expressed confidence in their understanding of how journalism works or the decision-making and newsgathering processes that shape how the news is made. Instead, many focused on more stylistic factors or qualities concerning the presentation of news as more tangible signals of perceived quality or reliability.

- The work of individual journalists, in contrast to presenters on television, was often far less visible, and many of the prominent media personalities who stood out to people were often polarising figures. When people spoke of individual journalists, it was often specific to outspoken personalities and opinion writers, even if they also made a point of saying they preferred impartial news that focused on facts rather than opinions. Many had an easier time naming presenters and commentators they disagreed with than highlighting the work of individual reporters or editors whose judgement and track record of reporting they respected. A considerable number in Brazil, the UK, and the US could not name any journalists at all.

- Perceptions of bias and hidden agendas in news coverage were prevalent, but what people meant often reflected differences in their own political or social identities. Objectivity, impartiality, and balance in news coverage were frequently invoked in all four countries as values associated with trustworthy journalism. While many criticised specific news brands or entire modes of news as being too driven by commercial or partisan interests or both, others were frustrated by the distorted ways they felt particular groups in society were portrayed – whether ignored entirely, demeaned, or consistently overemphasised. A belief that the news was ‘controlled’ by various forces led many to adopt a more generalised form of scepticism and resignation about whether any news source could be counted on for accurate information.

- Few cited the COVID-19 pandemic as a factor in how they evaluated the trustworthiness of news sources. While many raised concerns about health-related misinformation they had encountered or referred to news about the pandemic as being emotionally taxing, the pandemic itself did not seem to alter many pre-existing views about news media.

- Most had low trust in information they saw on platforms, but judgement of individual news outlets often depended on how strongly people already felt toward the brands they encountered there. Many valued the convenience of getting news via social media, search engines, or messaging services, but finding news there was generally a secondary consideration for why they used these platforms – even something they tended to avoid. For audiences without existing preferences (positive or negative) about news organisations in their country, making sense of the abundance of information online could be challenging or overwhelming. Because many perceived digital media as places awash in unreliable, divisive, and even dangerous information, there are clear trade-offs involved for news organisations that seek to appear in such venues in order to attract and engage with new audiences.

2. Trust as a shorthand for familiarity, reputation, and likeability ↑

In this section, we begin by examining what people said trust in news means to them and detailing several themes that stood out. First, we learned that people held wide-ranging attitudes towards various news organisations in their countries that are difficult to capture in commonly used survey questions. A person who was generally trusting of news often held more critical views about particular news organisations or modes of media. These views were routinely in line with partisanship or other key identities that shaped people’s worldviews. Second, while most said information accuracy was among the top factors determining whether an organisation was worthy of trust, how they interpreted factual accuracy was highly subjective and variable. When it came to specific news organisations, focus group participants and interviewees across the four countries frequently said they rely on brand-level impressions based on rules of thumb or context clues to determine which sources were reliable and credible.

2.1. Factors beyond ‘accuracy’

Sense of familiarity and attachment with brand or source

Many said they based their judgements about trustworthiness on how familiar they were with a given news organisation. As Pamela (28, woman, US) put it, ‘It’s always easier to trust someone you’re more familiar with’. On the other hand, if study participants hadn’t heard of a brand at all, this was often grounds to dismiss its reporting. Mariana (45, woman, Brazil) explained, ‘I’m usually not one to look at a website or platform that I’ve never heard of’. Sometimes this sense of familiarity was less about rational judgements than it was about intuition:

It’s hard to put it into words because it’s very instinctual, I don’t really think about it. I just have a general feeling, really. I suppose I just trust if it comes from a major publication that I recognise. If it’s some random page that I’ve no idea about, they rarely come up, but it’s more questionable.

Andrew (25, man, UK)

Many spoke about familiarity in relation to the formation of news consumption habits, which often dated back to their childhoods. Kayla (34, woman, US) described how she got accustomed to watching Good Morning America because ‘my mom would wake up and she’d watch it while she drank coffee, so I just got in that habit even when I was younger. And that habit stuck with me when I was out on my own’. Samantha (33, woman, UK) explained she ‘would be much more likely to go to the BBC, not because I necessarily think it’s better than any equivalent site, but just because it’s what I’ve been used to. My dad would have looked on BBC, do you know what I mean?’ Sometimes brands were even talked about as part of family tradition, reminding people of their loved ones. For example, Deborah (50, woman, UK) acknowledged, ‘As daft a reason as it sounds, I always remember my Grandad saying he would only trust the BBC, and I guess I grew up conditioned to think that’. Explaining why she trusts NDTV, Farah (40, woman, India) mentioned that she had been watching it for years and ‘my family members also used to like to watch it’. This sense of heritage alludes to a deeper form of attachment to news brands expressed by many of those who trusted specific organisations.

I grew up watching the BBC. … I grew up watching George Alagiah. Sometimes, you build that rapport with a presenter, and you think, ‘What they’re saying is correct’. I can’t get that with Piers Morgan and Good Morning Britain, anyone on those particular forums or channels. Channel 4, I can. It’s really odd. Maybe there’s something there, just because somebody’s saying it who’s in that position, that I’ve known all my life, I’m more inclined to trust that information.

Alice (34, woman, UK)

Trust did not, however, necessarily mean interviewees were blindly accepting of all of a news organisation’s reporting. As João (25, man, Brazil) said about G1, the brand he used most heavily, ‘I wouldn’t say that I trust completely, but it is the one I use the most and sometimes it is the only one I use. So, while it is the one I trust the most, it is also the one I most suspect’.

Reputation and past experience

Familiarity with a given brand was also closely intertwined with impressions about that media organisation’s track record and reputation. Having been around for a long time gave many confidence that an organisation was more deserving of trust. ‘Well, of course, there’s the history, they’ve got a long history of journalism there’, Mary (40, woman, US) said, for example, when asked why she trusted the Washington Post and the New York Times.

Similar points were raised elsewhere. When talking about why she trusted The Hindu, Pratibha (56, woman, India) underscored that alongside the Times, it is ‘the oldest’ newspaper and was also ‘the first one’. Similarly, Maria (37, woman, Brazil) offered, ‘I trust Globo group and Folha more because I think they’ve been around for a long time’. As Samantha (33, woman, UK) explained in her case when it came to the BBC, she wasn’t sure why she found it more trustworthy. ‘I think it’s because it’s like a big establishment. In England, it’s a big thing, it’s been around for a lot of years. I guess they have something they have to be accountable to.’

Indeed, some interpreted longevity itself as indicative of whether an organisation had rigorous reporting practices that had withstood scrutiny over time.

It’s more because if they are a big enough brand, an old enough organisation, they seem to have better practices. I guess there’s better regulations, I guess they get in trouble if they misreport facts. So, I think that is the main reason, the main deciphering of trustworthy news sources, and the best way to find it.Andrew (25, man, UK)

For others, assessing an organisation’s track record involved past encounters and evaluations about the nature of its coverage over time. Carl (64, man, US), for instance, recalled that he had listened to the ‘local National Public Radio in just about every place we’ve lived for the last 40, 45 years. I guess that’s the other thing, that sense of consistency over time that gives a level of credibility that maybe other places don’t have’.

In the absence of prior knowledge about a news organisation’s reputation or previous experience using it themselves, however, many said they would turn to people they knew and trusted to help decipher which sources were more accurate and reliable.2 Such practices came up in all countries but most often in India and Brazil. As Andrea (28, woman, India) said, when in doubt, ‘I will ask my friends if they’ve heard anything about it, my parents if they have heard anything about it’. In some instances, these trusted advisors were experts in particular subjects like politics or health. In other cases, people relied on more general perceptions of what they sensed other people thought about the trustworthiness of a given source, what Russell (28, man, US), a regular Reddit user for news, called ‘societal consensus’. Sometimes people turned to their acquaintances to stay informed when they distrusted conventional news media.

Nowadays, I no longer watch the news on TV. I’ve stopped doing that during the pandemic. I prefer the truth. We’ve been watching a lot of fake information going around. For example, I have a friend in Brasília so he tells us what he sees. In this group, each one lives in one part of Brazil so we tell others what we see, not what we watch on TV.

Rebeca (49, woman, Brazil)

Of course, reputations can cut both ways. For some, greater brand awareness was associated with greater distrust, not just trust. Pratik (32, man, India) made a point of noting, ‘I do remember the fake ones’, referencing a popular channel that ‘had discovered aliens a few years back’ and ‘were even researching about mermaids’. Others took note of brands whose identities they saw as contrasting with their own partisan or ideological views. As Jordan (23, man, US) said, ‘I can just think of specific news anchors on Fox News and hear things that they say that legitimately upset me or I think are very hateful’. In the UK, prominent tabloid newspaper brands were often singled out.

The Daily Mail has been shown or seen to be very sensationalist. They, I think, repeatedly put out information that’s always questioned and then obviously they have to retract certain statements, so that in itself is obviously another cause for me to be, like, ‘Hang on a minute, I probably shouldn’t take what I see on there for face value’.

Antoine (29, man, UK)

Generalising about entire modes or platforms

Many made determinations about whether to trust information based on broader categorisations of entire modes of media (e.g. television versus online versus print) or platforms (e.g. news on WhatsApp versus Twitter). The most common versions of this were pronouncements expressing scepticism about online platforms, for example, ‘I almost never trust content coming from social media, honestly’ (Lia, 43, woman, Brazil) or ‘Honestly speaking, I don’t trust WhatsApp’ (Andrea, 28, woman, India). In rare cases people made the opposite generalisations, such as ‘Social media, they keep in mind what is true’ (Raghunath, 46, man, India).

We focus specifically on perceptions about platforms in Part 5 of this report, but here we note that many also categorised conventional news sources based on broad assumptions they held about the format. For instance, some interviewees expressed greater trust toward online news because they assumed alternatives were less up-to-date and less relevant. Maria (37, woman, Brazil) explained that she preferred Folha’s news website over BandNews TV because ‘it’s an online company and it can change things throughout the day’, which in her view allows for more consistent and well-researched content amended with any necessary changes.

Some people also said they trusted television news because it provides visual evidence for what is being reported or because they were more inclined to believe ‘real people’ they could see. For example, Abhay (37, man, India) said, ‘I like to see the video, or maybe if I see the video I get to know, “Okay, this is happening around”. That makes things easier for me to judge it’. Similarly, Rafael (22, man, Brazil) explained, ‘I believe in information that is conveyed visually’. Samantha (33, woman, UK) suggested that ‘it’s easier to mislead people in print’ than on TV because she thought it was ‘harder to believe that somebody would outright lie to your face’.

2.2 How likeability relates to trust

In addition to familiarity and reputation, trust and distrust often served as a shorthand for what people liked or disliked about various news sources. Conversations about trust would often veer towards broader critiques and frustrations many felt about particular news sources – a way of explaining why they avoided certain channels or providers and used the ones they did. As Vitor (27, man, Brazil) said, ‘I trust in those sources I read’. Or as Mariana (45, woman, Brazil) put it, ‘I always try to watch or listen to the ones I am already used to, the ones I trust more’.

A focus on stylistic differences in how news is presented

Among the many critiques people offered about why they gravitated toward particular sources were those pertaining to stylistic differences in how news was presented. These criticisms and observations were common in all countries. Many focused on the style of the writing itself. Describing her dislike of the Guardian, Abigail (58, woman, UK) explained that ‘it just seems to be quite highfalutin’, adding ‘I just can’t get to grips with it’. The care put into copyediting also mattered for people like Rachel (23, woman, UK), who said, ‘When I open an article and I see it’s full of errors and spelling mistakes and grammar mistakes, I know that it’s not something to be relied upon’. In India, multiple people pointed to ‘good language’ as a signal of a news organisation’s quality or appeal, referring to characteristics of the syntax itself.

A lot of it has to do with language as well. When I see something that has been written well grammatically and otherwise, that does lead you to trust it because you can see that the person who’s written it obviously has studied a lot, has studied the language, has a good command of the language.

Pooja (21, woman, India)

The focus on stylistic differences especially stood out in India, where many seemed to differentiate between news sources on the basis of these factors. Geeta (46, woman, India) said she liked that a particular newscaster ‘speaks very nicely so I like watching him’, adding ‘style and the quality of news is also nice; he is very presentable’. Some commentary on the style of television programmes revolved around how aggressive the presenters were, a feature some experienced as abrasive and off-putting. Arshad (32, man, India) criticised the practice adopted by many journalists of ‘just shouting on TV’.

For Indian news, I would like them to remove those weird siren sounds during breaking news, and would like them to stop yelling and shouting, to put forward their point of view.

Kartik (25, man, India)

However, the tendency of Indian television news programmes to involve a great deal of shouting was a polarising stylistic element, as other people found it to be interesting and appealing to watch. For example, Abhay (37, man, India) explained that he appreciates the confrontational style because he enjoys the drama: ‘If something has to be portrayed they will shout and portray it, so there is a different weight on that. I love watching them. Even if I don’t want to, they’ll keep a suspense until the end’. (We pick up on this theme again in Part 3 when we examine how interviewees talked about individual journalists.)

Appearance

In addition to the language and style used in reporting and presenting news, some interviewees highlighted the importance of the appearance or aesthetic characteristics of news, primarily in relation to advertising on news websites and videos. Often, comments about appearance directly touched on the functionality and usability of websites. Farah (40, woman, India) complained about interruptions of ‘ads that keep popping up in between, that’s very irritating’. Ângelo (28, man, Brazil) said he preferred sites ‘with few ads, which leads to less visual pollution in the screen and [content] being more accessible with just a few clicks’. Similarly, Luke (51, man, UK) explained, ‘I tend to avoid even watching the videos on the internet news because they’re surrounded by adverts that you have to sit through before you can skip them’. Others used the aesthetic characteristics of websites as indicators of the news quality itself.

I’m very wary of what the website looks like. If there’s a lot of pop-ups and lots of different photos of different things and it’s quite a clogged website, I tend to not trust the news as much. It is a weird way of thinking, but if it’s not as posh-looking, I tend not to trust it as much.

Gemma (23, woman, UK)

Several people talked specifically about the appearance of their local news websites in unflattering terms. Hannah (28, woman, UK) explained that she avoids ‘“spammy” websites with loads of pop-ups and adverts’, adding that her ‘local news provider is a major culprit for this’. Joseph (33, man, UK) was sympathetic to news outlets that financially depend on advertising, but nonetheless said he avoids his local newspaper because of the annoyance of excessive ads: ‘I just won’t go on it because the website takes a long time to buffer and the ads just pop up halfway down the story. It’s not very pleasant to navigate, it’s not very aesthetically pleasing on the site or anything like that’.

Sensationalism and clickbait

Across all four countries, another stylistic concern involving both the substance and presentation of news was the reliance on sensationalism or clickbait, which was typically associated with lower quality information. For example, Pedro (35, man, Brazil) maintained that ‘if they [news outlets] exaggerate, I’ll know it’s false’. The distaste for sensationalistic journalism was often anchored in the feeling that such news simply sought to provoke or trick audiences into clicking or watching. Antoine (29, man, UK) explained that he pays close attention to the tone of headlines because you can tell ‘if something is being used to just rile people up or … you read a headline and then you read the rest of the article, you’re like, “Hang on a minute, that’s not even what you’re saying in this headline”’.

Some of the headlines [on CNN] are ridiculously misleading. Of course they are, they want you to click on it. So, I find that very annoying sometimes where I click on something and then I say, ‘Oh, for crying out loud, I totally got suckered on that stupid headline or summary of what I’m going to see’.

John (39, man, US)

In the UK, study participants were especially likely to single out tabloid newspapers when referring to sensationalism. Gemma (23, woman, UK) explained that she wasn’t the ‘type’ of person who reads such papers, but she could see their appeal to others: ‘Tabloids tend to be very right-wing, very clickbait, very much “a version of the truth”, just about. I find a lot of their news articles are quite racially aggressive and very distasteful, but to an audience that they’re trying to capture, it works.’ Another interviewee argued that while approaching tabloids with scepticism, it is unnecessary to entirely exclude them from one’s media diet:

I wouldn’t say I would totally disregard them [tabloids] because to disregard them would be, you know, you’re cutting off essentially a whole area of the news. And … I don’t think any of those news articles are so far away that they’ve got no truth in them. They just, I guess, they pad out things a little bit more based on who they think they’re tailoring their read to.

Alexander (35, man, UK)

A small number of interviewees acknowledged enjoying news others might call ‘sensationalised’. Many did not assume the information was always accurate, but this didn’t prevent them from enjoying it. For example, Gabrielle (22, woman, UK) explained that she read the Daily Mail mostly for entertainment and didn’t worry about verifying the information because ‘It’s not something that I really care to know if it’s true, if I’m honest. It’s not something I take at face value either’. Others pointed out that sensationalism only existed because there was a real demand for it.

We don’t want calm peaceful news; we want to see something sensational. It’s the people. So the channel which is showing something sensational, people watch more.

Kavita (43, woman, India)

A focus on how news makes people feel

When describing how likeable a particular news channel or source may be, many referred not simply to how credible they believed the information was or the stylistic choices made around presenting it, but how consuming such news made them feel. These affective responses were often important for understanding why people said they trusted certain sources versus others. Gemma (23, woman, UK), quoted above about her preference for ‘posh-looking’ websites, explained how a site’s appearance affected how she felt about it: ‘there’s a feeling of ease when you read something that’s clean, clear and precise, well-written. I feel more relaxed and therefore more likely to trust it, to be honest.’ Lawrence (55, man, US), a conservative supporter of Donald Trump, described removing news apps from his phone following the 2020 election and refusing to watch Fox News or any cable news. Although he remained steadfast in his views, he recognised the effect quitting this news medium had on his mood: ‘To be honest with you, I think you’re less angry.’

When I’m watching Channel 4 News, I definitely feel more relaxed than when I’m watching BBC News. It’s maybe to do with the sort of setting and the environment. Channel 4 is definitely more relaxed and chilled out in terms of their set and the way they report things, the mannerisms of the presenters and things like that as well.

Joseph (33, man, UK)

Most often, the kinds of feelings people associated with news were those causing distress, such as anxiety, anger, or fear. Rebeca (49, woman, Brazil) recalled an episode in which something she saw on TV led her to believe she had COVID-19. ‘I had breathing issues. Thankfully, it was only for one night, but it was a horrible experience. That’s when I promised myself to stop watching the news on TV.’ Danielle (25, woman, UK) also viewed news coverage as potentially harmful, explaining that ‘with how much of the media reports negative stuff over positive stuff, people in general have become more anxious and negative themselves’.

The focus on the emotional impact of news also meant people did not always differentiate between events in the news and the editorial choices made about how to represent those events. Henry (48, man, US), for example, said he did not bother paying close attention to the reputations of sources and their biases; he just wanted the basic facts and relied on aggregators like Bing or Yahoo! to simplify his news consumption. ‘I’m like a hoverer where I want to know what’s going on, but I just don’t have the time to be point/counterpoint of each issue.’ Others felt similarly:

I am not in favour of any [in] particular. The news is important; medium is not important.

Kavita (43, woman, India)

3. Attention to journalism practices, but limited knowledge about it ↑

In our previous report (Toff et al. 2020), which focused on journalists’ perspectives about trust in news, reporters and editors we interviewed talked about the importance they placed on newsgathering and reporting procedures as markers of quality. Here we turn to what audiences think about journalism practices: what expectations do people have for news? How well do the sources they use meet those expectations? And when people sense that news falls short, what do they do about it?

In this section we highlight how study participants made assessments about journalistic practices in Brazil, India, the UK, and the US. We also focus on views about individual journalists, who were only in rare cases seen as independent and distinct from the organisations they worked for.

3.1. What people say they want from news

Although many focused on factors like familiarity, presentational style, and appearance when describing their own media choices, when it came to expectations about what ‘good journalism’ means, study participants did sometimes raise matters involving news organisations’ editorial practices. To take one example, a select number of interviewees, primarily in the UK and the US, talked about the importance of correction policies as evidence of professionalism, which made them more trusting of news. Jeremy (57, man, US), for example, said seeing corrections made him more likely to trust a news organisation: ‘If they just ignore their own errors, well, that’s a problem, and the sooner they catch the error, the better, of course.’ Likewise, Alexander (35, man, UK) was forgiving of news organisations when they made mistakes and said he respected journalists who sought to correct the factual record, ‘At the end of the day there are humans writing these things’.

Professionalism

More often, however, the kinds of qualities people said they wanted from journalism were less tangible and concrete. Many emphasised forms of ‘professionalism’ more generally, underscoring the importance of reporters pursuing stories ‘in-depth’ and asking ‘hard questions’. These notions were not always rooted in any specific practices but in brands’ overall reputations for holding themselves to evidentiary standards and being intellectually honest. In some cases, more trusting study participants pointed to professionalism as being a kind of quality that could even overcome partisan disagreements. An American interviewee, for example, mentioned that he liked New York Times opinion columnist David Brooks due to what he perceived to be his integrity, even though he disagreed with his political views.

I guess he’s a journalist that is also quite a thinker, and what I liked about him is just he’s a thinker, he thinks deeply, and he really cares about the wellbeing of society. His values, within that spectrum, political values spectrum, he’s to the right of me, but it doesn’t matter because I can see that he cares, right? He cares and he thinks deeply about the country and the society and people, and someone like that, he’s got integrity. That’s the word, integrity is the word. So, I listen to what he has to say. Even if he says something I do not necessarily agree with, I listen to him and I take it as a lesson. Unfortunately, there aren’t that many people like that anymore, but he is one of them.

Jeremy (57, man, US)

In-depth reporting

Closely intertwined with professionalism, participants in all four countries often underscored a preference for in-depth reporting, expressing that they placed importance on reporters asking hard questions and adopting comprehensive research practices. ‘I think research is everything’, Pooja (21, woman, India) said, for example. She argued that journalism needs to explain what is going on beyond simply presenting a set of facts as if they speak for themselves. ‘It’s important to interview people who are experts on a topic’, she suggested.

For me personally, something’s well-written when there are a lot of viewpoints that have been examined. That specific article [where] the Constituent Assembly debates were examined, like what happened? What was the thought process of the members of the Constituent Assembly when they were drafting this particular article? What was the intention behind it? That is something that is very important to know when you want to form an opinion about something. … So, it’s not really somebody’s opinion, but it’s just somebody who’s put in a lot of research in their writing, so that to me is well-written – when you can just see the effort that somebody has gone through to write something.

Pooja (21, woman, India)

Similar sentiments were expressed by others who brought up the value of asking ‘hard questions’. Lawrence (55, man, US), for example, said he wished news resembled ‘the way things were’ in the past. ‘You weren’t getting this constant 24/7 stream of, really, BS, and nobody does their research anymore. Nobody asks questions. It’s really, kind of, sad. It’s actually tragic, to be honest with you.’ Others lamented what they saw as superficial news coverage, especially on television, which many used as a cue that the information being reported might be less reliable.

I see this on Good Morning Britain. It’s just over-simplified. It doesn’t really give the required depth for people to understand what’s going on. Maybe those people are happy not to know what’s going on, I don’t know. I watched the news today, I watched Good Morning Britain. It was very simple. Are you really well-informed if you’re watching that?

Alice (34, woman, UK)

In-depth reporting, however, was not consistently viewed as a trust-inducing quality. To the extent that depth also meant complexity, some viewed it as an annoyance. One interviewee, for example, said that under certain circumstances, he preferred news that was more ‘straight to the point’.

I obviously enjoy podcasts, I enjoy drawn out conversations about different implications and things like that, but when it comes to breaking news or something that’s happening, it’s important to just say, ‘X, Y, Z, these are the facts, this is what’s happening’. And I think that I’m drawn to journalists who do that more.

Jordan (23, man, US)

3.2. What people say they get from news

While the above examples capture some of the values people say they expect of high calibre journalism, people across all four countries often described a different set of characteristics when it came to news they actually encountered. Here interviewees often brought up the repetitive nature of news and its lack of relevance to their lives. Many even saw news through the lens of entertainment, evaluating it accordingly as a source of information where trustworthiness was not always an important consideration.

Repetitiveness

Chief among the critiques participants had about news was that it was often tediously predictable, cyclical, and never changing. This mattered for trust because it also meant that many saw news generally as largely interchangeable from one source to the next.

In all four countries, people expressed some degree of disappointment that news was so often repetitive in this way. In some cases, as in the following, perceptions of repetitiveness were connected to people’s own partisan points-of-view, but in other instances, interviewees would mention COVID-19 or other prominent stories as examples of precisely what annoyed them about coverage, as though such frustrations about news applied broadly to all producers of news.

Respondent: They are always repeating the same things. Always insisting on the same information, but at a different angle. It’s tiring to hear that.

Moderator: What is the repetitive information?

Respondent: COVID, corruption, lockdown, Bolsonaro doing the wrong things. It’s always the same. Just watch the news and you’ll see it.

Moderator: Do you think the problem is because these things happen and the media keeps talking about them, or do they not happen at all?

Respondent: The media explores the content for the audience. Those things don’t happen too often, though.

Ricardo (44, man, Brazil)

For some, the perceived repetitiveness of the news translated into beliefs that there were ultimately few differences between sources, as though news organisations were duplicating each other’s work rather than contributing original reporting of their own. This often resulted in participants viewing brands as interchangeable. Henry (48, man, US), for example, described trying to parse through different sources he might encounter online when he searched for stories about an event in the news: ‘It might be that if I had gone down to the eighth one on the list I would have gotten the single best explanation, the best statistics, whatever, but that’s the problem: we have too many people who do the same job in this world.’ In another example, Pratibha (56, woman, India) said she thought ‘all the channels’ reported misleading information in much the same way. ‘No choice, I have to accept it.’

Lack of relevance to everyday life

One of the concerns many raised about news coverage in their country was that too often it did not seem relevant to their lives. We say more about this subject in the next part of the report, since often this critique overlaped with concerns about news not representing people’s lived experiences, which we heard especially from marginalised groups. But more generally, and especially in India and Brazil, many raised concerns about news failing to address matters that would make a difference in how they lived their lives.

These kinds of frustrations about news being out-of-touch relate to trust because many see it as a consequence of news organisations ultimately prioritising their own interests. ‘The news today isn’t focused on helping people’, said Ricardo (44, man, Brazil). ‘Nobody talks about the price of goods, the cost of utilities in other states. There aren’t any details like that. The news is solely based on what is popular, what makes people watch. It’s what brings in more audience.’

They’re not reporting the struggles that these farmers are facing. Most importantly, this is not breaking news and people might not be interested in such news. It’s the mentality of Indians, that, ‘Who cares what is happening to others? Just stick to yourself’. That doesn’t mean that this news is put in the back of the newspaper or somewhere in the corners where people are not even able to notice. The sports news gets a lot of highlight because there will be an entire section dealing with which player is supposed to retire or which player is playing or not, which is pretty, I feel, useless.

Pratik (32, man, India)

Line between news and entertainment was often blurry

In many cases, across all four countries, interviewees would often make clear that the way they evaluated news was not always necessarily as a source of information but as entertainment. Sometimes this was offered as a rationale for why a particular news source was not to be trusted. In Brazil, for example, several interviewees mentioned violent television shows they disliked as a reason for distrusting news. Ana (32, woman, Brazil) singled out a programme hosted by José Luiz Datena, ‘They manage to distort reality to the point we are scared to go out on the street’, adding ‘these programmes make this circus out of a news story that is very serious’.

When describing impressions of the news media more generally, people in all four countries would often single out celebrity news in particular as an example of news they dismissed as having little informational value. Many drew a distinction between ‘serious’ news and this other form of news, which they thought too often bled over into coverage of the former.

I have a massive problem with reporting of celebrity. That is not news, that is gossip column. Gossip column is not news. What a celebrity thinks about politics isn’t important to me. They’re not informed in the subject area, stick to your lane, stay in your lane. Talk about acting, if you’re an actor.

Alice (34, woman, UK)

You know, the news about celebrities, like the news about big people. The names that have a big title attached to them. I feel that this news is pretty much hyped up. They are supposed to cover the breaking news first of all. They are supposed to cover the largest sections of the newspaper and the most important news is covered in the smaller sections of the newspaper. Not only this, but apart from them, this celebrity news is made pretty much more attractive by varying fonts and colourful fonts and so many things.

Pratik (32, man, India)

In the US, such critiques were sometimes made through a partisan lens, with interviewees perceiving opinionated content as strictly entertainment. ‘Fox News is not a news channel. It is an entertainment network’, as Henry (48, man, US) put it. ‘They do not present truth; [they add] their twist on what is news and add their opinion to make it the “truth”.’

3.3. How people bridge the gap when navigating news

As is evident in the examples above, the gaps identified between people’s expectations around news and perceptions about what they get were often focused on critiques about the content of news and less on the editorial practices behind it. One reason why actual practices of journalism were less central to how people seemed to think about trust may be because few expressed confidence in their knowledge about what reporting the news actually entails. Instead, they tended to rely on various heuristics or other cues about what might be decent proxies for professionalism and quality.

Often limited understanding about how news works

Previous research in the US has shown considerable limits to the public’s knowledge about basic journalistic practices (Media Insight Project 2018). We found similar gaps in understanding, which were often revealed in subtle ways. Study participants would refer, for example, to pop culture references when describing their sense of how the news works. Sticking with Henry (48, man, US), to take one example, when asked if he had a sense of ‘what goes on day-to-day in terms of reporting the news’, he responded by recalling the Jim Carrey movie Bruce Almighty. ‘I’m just picturing how he would show up to a scene and there he’d have his camera crew and everything, and they’d report on something.’

They’re going to be right there on the scene, but if there was some major event in a rural area but really major, they’re going to rush to that scene. There are going to be a bunch of camera crews and that kind of stuff. Then I know you have a bunch of writers behind the scenes that write the stories so that the broadcast journalists can read it on the teleprompter, and that’s what the public gets. They’re clearly biased somewhat, but I’m sure that there are editors who try to not be biased.

Henry (48, man, US)

As in this example, many drew on stereotypes or vague impressions they had about how journalists did their jobs as a substitute for direct knowledge. ‘I believe it’s like that; they search for the news’, Rebeca (49, woman, Brazil) said, referring to journalists’ tendencies toward sensationalising, or as Shrikant (57, man, India) put it, ‘I have a feeling that the journalists are being led to talk [about] something’.

Of course, there were exceptions here. Some did refer to formal journalism or media literacy training they had received in school, but such responses were atypical. Many instead referred to uncertain ideas they held about the profession, and they were sometimes unsure whether such notions were accurate. ‘I’ve always had the impression, you know, there’s that saying “don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story”?’, Luke (51, man, UK) said while describing what he imagined reporters on ‘Fleet Street’ might look like: ‘grizzled middle-aged men, hard drinking, spending a lot of time in the pub, quite militant’. He added, ‘I’m probably being unkind now, but that will probably be my impression – that they’re doing this for their own benefit to a certain extent’.

Reliance on heuristics

Many interviewees described using shortcuts, heuristics, to bridge this gap between ideal news and their actual experiences using news. Most often, participants mentioned tools and techniques that could inform, such as cross-checking and Googling to verify information, which we explore in Part 5 of this report, or turning to other people in their lives whom they trusted to offer guidance on brand reputation, which we described in Part 2. In other cases, interviewees sometimes said they relied on cues embedded in news content itself, such as focusing on numbers or statistics or visual signals perceived as more trustworthy than text.

Many saw these kinds of concrete cues as indications that journalists had carefully studied the underlying situation they were reporting on. Participants in the UK, US, and Brazil especially brought up this tendency to look for references to data and statistics as a heuristic for quality.

It is super important that the news are detailed with sources, statistics, and graphs, and seen from several different perspectives. This brings more certainty and credibility to the information.

Júlia (31, woman, Brazil)

I also like that they actually present a lot of facts, numbers, and stuff like that, and they’ll show you recordings of stuff that’s happened. I don’t see as much of that on other networks.

Raymond (57, man, US)

In other cases, study participants said characteristics of the medium itself could make information seem more or less trustworthy. Many said this was specifically the case for visual information compared to text, because the former allowed people to see what happened for themselves. One respondent (Preeti, 43, woman, India) described how written language was less trustworthy because there was no proof that an event in question actually happened, while another (Sherry, 32, woman, US) described focusing on the timestamp on raw video broadcast on television as a sign that a story was likely to be more credible.

3.4. The visibility and invisibility of individual journalists

The degree to which study participants could speak in depth about their views of individual journalists varied widely, and the specific journalists who were most often singled out were frequently cited as exemplars of ‘bad journalism’ rather than as role models for the profession. There was also a high level of convergence in the names that respondents talked about, with study participants often highlighting prominent figures such as William Bonner in Brazil, Arnab Goswami in India, or Piers Morgan in the UK.

Who reports the news attracted less attention than who presents it

When asked to describe specific individuals they associated with news, a select few said they paid attention to individual journalists as factors when it came to their own trust in news. Antoine (29, man, UK), for example, said he took note of the ‘byline itself – who’s actually written it – and who they are and what their previous work has been and what their reputation is on the whole’. But more typically, people focused mainly on those who deliver or present news, especially on television, and were unsure about the individuals who wrote and reported news behind-the-scenes. This was true even among those who consumed news frequently.

Most also had difficulty recalling names of journalists when asked about examples of individuals they either admired or distrusted. As Lara (38, woman, Brazil) said, ‘There is a girl at CNN… She even left, but I really liked her. I cannot recall her name. ... She’s young, and I really liked her’. These kinds of exchanges were typical, with some saying, as Alexander (35, man, UK) did, ‘It’s a bit like asking me to give you names of actors, I can tell you the headline names but I couldn’t go into individuals that contribute to all the news I read’. In some cases, people followed journalists directly on social media, but even there, they often had difficulty remembering the individuals they followed, or reported primarily being familiar with them from their presence offline.

There were, however, some revealing exceptions. Indian interviewees were particularly quick to name television personalities, excited to speak about them, and often had strong opinions about the journalists they named, more so than in the other countries. This extended even to those who otherwise avoided news. This underscores one of the differences between these countries: in India, where TV news seemed especially likely to be viewed as a medium for entertainment, journalists’ names were more easily recalled. But in Brazil, the US, and the UK, the content of news itself seemed to overshadow specifics such as reporters’ identities.

The brand as a symbol of its journalists

As noted above, many were unsure about what exactly went into original reporting. Often this also meant that people made few distinctions between journalists and the organisations they worked for. Many said they used their perceptions of the brand as a cue for how they thought about the journalists employed there. For example, when Rebeca (49, woman, Brazil) was asked about distinguishing between the two, she said, ‘The journalist is bound to the company, so he must obey. That’s what happens at Globo. If they don’t follow the rules, they are fired’.

Others made similar assessments about differentiating at the brand level. Pooja (21, woman, India) said, ‘Today I think effectively Arnab Goswami is synonymous to Republic, so I think the lines have blurred between media houses and their journalists’. Similar sentiments were expressed by some Americans as well. As Sherry (32, woman, US) said, ‘I think there is a link between the journalists and the organisation they work for. Most times the journalists work to project the image of their organisation. That is the way I feel’.

Polarising exemplars

On the occasion in which individual journalists were discussed, interviewees often held very strong opinions about them, speaking about them as exemplars of good or bad journalism. In the UK, respondents repeatedly talked about the style of television anchors, often pointing out instances of what they deemed as overly ‘aggressive’ journalism. Deborah (50, woman, UK), for example, said she liked Piers Morgan because ‘he is not afraid to ask any question’, even though she wished that he would ‘give people a chance to answer him, rather than just shout at them!’3 Others felt strongly otherwise.

Oh, no. Good God, no. How the hell he’s [Piers Morgan] not been sacked yet, I don’t know. He had a boycott from the whole of the UK Government, didn’t he, for the way he speaks to people. There’s robust interviewing and there’s downright being rude, and he’s downright rude.

Christopher (44, man, UK)

In India, respondents repeatedly talked about Republic TV’s anchor Arnab Goswami but held polarising opinions about him. While some appreciated his bold and loud questioning style, for others the same features were a negative. These polarised views were largely synonymous with respondents’ partisan identities, but sometimes gender overshadowed partisanship, with women expressing their dislike for him despite agreeing with him politically.

After Sushant Singh’s case, [Arnab Goswami] became famous. He is quite aggressive. Previously, he used to talk very calmly and slowly, but after he became the chief editor of Republic India he became so aggressive. I enjoy watching him on TV. He is the only anchor who has the guts to abuse and shout at his guests on a live TV show. He speaks so loudly that I need to keep the volume of the TV at 1.

Rajendra (31, man, India)

Arnab Goswami of Republic TV does not like Congress so he often uses bad language about them, which is not fine. I myself am inclined towards BJP, but still it makes me feel bad. News shouldn’t be of such type.

Geeta (46, woman, India)

In Brazil and the US, opinions around journalists tended to focus not only on style but also on content. While respondents did speak about journalists’ personalities, their conversations also revolved around whether the journalists themselves were trustworthy, knowledgeable, or reputable. Mário (55, man, Brazil), for example, said he respected the Brazilian news anchor Ricardo Boechat because ‘he had a perspective – no, a way of hosting – that was unmatched’, noting the way he could combine criticism ‘while also remaining on topic’. Regina (72, woman, US) said Lawrence O’Donnell was her favourite journalist on MSNBC because of his expertise, ‘because he used to work on the Hill, he has [the] best knowledge of what is actually going on’.

4. An elusive pursuit of balance and impartiality ↑

One of the other major aspects of journalistic practice that people often referenced as important to how they thought about trust in news concerned objectivity and impartiality. These kinds of observations about bias and balance, which are the focus of this section of the report, often emerged during critiques of what people perceived to be the failures of the news media and were sometimes held up in contrast to nostalgic ideas about impartial news media of the past.

4.1. Protecting oneself from being misled

Different definitions of impartial news

People often expressed complex – and even contradictory – understandings about how norms around objectivity should be enacted (if in fact they were possible), what constituted violations of these norms, or how issues like bias do or do not affect news consumers.

In many cases, differences arose around interpretations of specific events in the news, which many saw through fundamentally different lenses. As Robert (43, man, UK) put it, ‘Over the last couple of years, everything’s become a bit more polarised: Brexit, lockdown or not lockdown – everyone has to have one side or the other’.

Some believed objectivity and impartiality meant keeping opinions out of the news entirely (e.g. ‘I just want the facts and I’ll make my own opinion’ [David, 29, man, UK]). That often meant boiling news down to its essential black-and-white characteristics. John (39, man, US), for example, said he thought an ‘impartial journalist’ was someone whose only agenda is ‘just to give facts and not their opinion of the facts or their opinion of the reports coming out’.

Others emphasised that impartiality meant greater transparency around where opinions played a role in coverage. As Pooja (21, woman, India) said, ‘Of course, everybody has opinions, it’s a very human thing, but when you’re in a profession where there is a need for you to report objective facts, I think you should be able to separate those two’. Joseph (33, man, UK) said he appreciated opinionated takes on the news, so long as ‘they make it really clear that it’s that analyst’s viewpoint and it’s the analyst’s words that are saying it’.

Still others believed news with a political inclination was fine (and often more interesting), just so long as it didn’t go too far. ‘Tilt is okay. Okay, he is supporting that, fine’, Shrikant (57, man, India) allowed, while also noting ‘there is difference between being supportive and being biased’. Many, although not all, further recognised that their own interpretation of what is factual depended on their own subjective point of view. As Ângelo (28, man, Brazil) said, ‘Total impartiality is impossible. We’re human’.

Generalised scepticism (taking news with ‘a pinch of salt’)

Although interviewees often disagreed about what they meant by impartial news, many were convinced that the best way to respond to pervasive bias in coverage was the same: generalised scepticism or distrust of all news outlets as a form of protection from being misled or manipulated. This attitude has been captured in previous research (Fletcher and Nielsen 2019) and, indeed, many in the US and UK said the same verbatim phrase that they took news with ‘a pinch (or grain) of salt’. Luke (51, man, UK), for example, said the phrase while quoting Denzel Washington in the movie Training Day: ‘He holds up the newspaper and says, “It’s 90% bullshit, but it entertains me and that’s why I read it”. I have that view.’

Although people in Brazil and India did not use the same language, they described similar attitudes.

I won’t say 100% is true and 100% believable. We need to think proportionally about it, and we need to search and then trust, not trust blindly anything.

Kavita (43, woman, India)

Degree of certainty? Well, I do not have it. Nowadays, what I have the most in my country is uncertainty. It is hard to deal with uncertainty. If I had to put a number, I would say 50%. I read and believe in 50% of it.

Lia (43, woman, Brazil)

Generalised scepticism was particularly evident among those who did not have loyal and trusting relationships with any specific brands. As Russell (28, man, US) said, he tried to use ‘as many different sources as I can, as I have the attention span for’, because he was certain that ‘getting all your news from one source … just seems like a recipe for disaster’.

4.2. Perceived agendas behind coverage

One of the most common complaints we heard about news media was the perception that they were motivated by agendas other than a desire to inform the public. In their most extreme version, these consisted of somewhat vague, unfalsifiable conspiratorial ideas about shadowy figures or forces pulling the strings – perceptions held by a handful of people mainly in the US and UK. In their view, some unknown power was responsible for co-ordinating news coverage towards certain topics or covering up others. In these instances, interviewees sometimes referenced ideas about ‘investigative journalism’ that would ultimately expose the true nature of these influences. Abigail (58, woman, UK) illustrated that by saying ‘somebody somewhere or some organisation is controlling almost what we get to hear as the news’.

In another example, Lawrence (55, man, US) raised a series of questions similar to those circulated by supporters of the QAnon conspiracy theory, referencing reports about trafficked children: ‘They pull over a truck in, say, Michigan, and there were 32 kids in the truck. Basically, that’s been happening every month now where they’ve been rescuing these kids.’ Lawrence saw the media’s failure to ask questions and connect the dots as evidence of a deliberate cover-up.4

When has law enforcement ever stopped an investigative journalist from doing their job? Look at the guys that did the Watergate investigation. Come on, there had to be a lot of people stepping in their way trying to prevent that kind of information, but they kept digging and they kept dripping out information.

Lawrence (55, man, US)

Partisan and commercial agendas

Much more often, concerns raised by study participants about agendas influencing the content of news were typically those regarding commercial or partisan biases, which were understood to be pervasive across all four markets.

The media is not working for the people anymore. It’s not working from the perspective of people anymore. It is driven by the agenda of political parties. That kind of journalism will not really succumb to what people have to say.

Arshad (32, man, India)

While some people were more generous in their interpretations, for example, explaining that profit motives were to some extent inevitable (‘They must adapt the content based on what kind of audience they are focusing on. You cannot sell the same product to classes A, B, C, and D.’ [Mário, 55, man, Brazil]), others were more critical about the intentions underlying these agendas and their perceived consequences.

I think the challenge is the financial interest. You’ve got people who are motivated by how they’re making money for the content they’re producing, and they get more content by producing more and more divisive articles and content, and that furthers this divide. So, that is dangerous, I think.

Jay (39, man, US)

Many perceived direct links between news organisations and politicians or political parties, especially following divisive political events. Jay (39, man, US), for example, saw a clear agenda in how networks presented news after the 2016 US elections. ‘Nowadays, I read the news anticipating there’s an agenda being told for me and it’s being presented from one side rather than a non-biased source.’ Many said they thought news organisations’ partisan agendas could harm trust, even when people agreed with it. Rebeca (49, woman, Brazil) said she thought news had ‘got too political’. She questioned motives in particular, ‘It’s a matter of personal benefit, trying to achieve something on someone’s behalf – not on the citizen’s behalf’.

I am against Bolsonaro. But I know Globo exaggerates. When Globo wants something, they get it. They went against Dilma and they won. When they want something, they invest in news to favour them. They dislike Bolsonaro so they do everything in their power to oppose him.

Rebeca (49, woman, Brazil)

Many also saw commercial and partisan agendas as highly intertwined, such as Ricardo (44, man, Brazil), who said he thought choosing sides politically was often a business decision. ‘It’s lucrative to have someone backing you up, telling you what to say. The independent sources are small, they don’t have much money and they have a small structure. No one assists them.’

Country-specific differences around perceptions of corruption

The salience of certain issues stood out in some countries more than others. Interviewees in India were more likely to discuss overt corruption and manipulation. From their perspective, news organisations knowingly and selfishly try to trick or deceive their audiences with the goal of advancing their own interests. In some cases, this was rooted in prominent instances of corrupt media practices – for example, the memory of previous ‘paid news’ scandals (Press Council of India 2010) – but such practices were often perceived to be prevalent today.

Most of the channels are being run by some or another political party or maybe with some close persons with that. ... As we have heard this thing that news channels are the pillar of democracy, this is all the dialogue, but the news channels are mostly propagating only for the party’s point of view, they are white-washing all their scams.

Jatin (33, man, India)

In Brazil, many mentioned a perceived patronage relationship between the media and elites. Different from India, however, such perceptions were less anchored in concrete events than in impressions that mirror a notable malaise about institutions in the country more generally (Latinobarómetro 2018; Instituto Sivis 2020).

Big [media] companies have a say in the political sphere. Big companies go around Brasília, Capital of Brazil, to lobby. … They seek exemptions, benefits, concessions, and in exchange they offer other spaces. In general, big businessmen go to our capital to lobby more than our politicians.

Lia (43, woman, Brazil)

These kinds of concerns about corrupt practices echo sentiments we sometimes heard in the US and UK as well.

Unfortunately I think our society does believe that anything can be bought and needs to be paid for, so I don’t believe it is ever truly independent. It does need to be free of political influence (and should not be tied to the government).

Pamela (28, woman, US)

Country-specific differences around focusing on ownership

The role of ownership in shaping news coverage came up frequently, but primarily in the US and UK. Laura (54, woman, UK), for example, said it bothers her that news organisations ‘might choose not to report things that reflect badly on politicians in power because they are supporters of that party or donors to that party’.

Concerns about the influence of ownership in some cases led people to assert the importance of transparency about such matters. Pooja (21, woman, India), for example, lamented that in India, ‘there is very little transparency on the ownership of media houses’. In the US, some saw transparency as an asset for building trust.

I guess I equate transparency with truth, and if they’re truthful about their affiliations, about the things they might not want to be truthful about, then that would lead me to believe that they’re more truthful about their reporting.

Mary (40, woman, US)

The role of public service media was also celebrated by some interviewees, especially in the UK and to a lesser extent in the US, while it was barely mentioned in Brazil and India. People often mentioned the BBC in the UK or PBS and NPR in the US as being less constrained by the commercial interests of their for-profit counterparts. When referencing the BBC, some also touched on the more stringent regulations imposed on broadcast news, which gave them a sense of greater accountability.

I think there’s something about the BBC because they’re meant to be – well, you don’t have adverts, etc., so it’s not about making money.

Robert (43, man, UK)

Some expressed concern about the BBC getting too cosy with the government in recent years, perceiving that ‘BBC journalists are not offering enough challenge, for example, to our politicians’, as Laura (54, woman, UK) argued. At the same time, those who were more trusting of news believed that being publicly funded likely implied greater editorial independence. Russell (28, man, US), for example, said he thought not being commercially oriented probably allows NPR ‘to be a little less biased’.

4.3. Representation matters

We anticipated that ideas about bias and impartiality, for some, might be rooted in their own identities and perceptions about whether the news media in their countries fairly portrayed people like themselves in coverage (Toff et al. 2020). For that reason, we included questions on the subject in our interviews and focus groups designed to better understand what role such views might play in shaping attitudes about trust in news. Here we detail some of the concerns we heard most often.

Different views about the role of identity

Interviewees understood questions about representation very differently depending on which characteristics of their own identities were most salient to them. For example, some talked about what they felt were misrepresentations of their profession (e.g. teachers, scientists) while others spoke about their gender, age, or the place they lived. Those who were most critical of news, who often believed key perspectives were missing, tended to be racial or religious minorities in their countries. Because such individuals also made up a small part of our sample, these concerns did not come up as frequently. Nonetheless, we highlight them here because such critiques might otherwise be overlooked if researchers and journalists only focus on the most common responses at the aggregate level.

While issues of representation were important to this subset of people, we note that many others interviewed were much less concerned about such matters. Some even challenged the notion that seeing their own identities reflected back in coverage had anything to do with good journalism.

Well, do you want them to [represent you]? ... That’s the thing at the end of the day, that’s not really the point in journalism. Journalism isn’t to represent people like you, it’s to, maybe, provide a view of the world that you don’t necessarily see yourself.

Alexander (35, man, UK)

In some of the channels, they say ‘One Muslim killed in road accident’, ‘One Dalit person killed in road accident’. Do we require this particular sort of information? The truth is one person is killed. Why do you bring the caste system here?

Raghunath (46, man, India)

While such sentiments were primarily expressed by those who were themselves part of the dominant groups in their country (for example, white men in the UK or people from dominant castes in India), there were exceptions here as well. For example, as Mehdi (47, man, UK) said, ‘I want news that is accurate. It doesn’t need to be delivered by a middle-aged, Middle Eastern gay man’.

Race, religion, caste, and class

A perceived failure of the press to represent racial diversity was most commonly discussed in Brazil, the US, and the UK, and was far more likely to be raised by people of colour than white interviewees. The main concerns raised, which were strikingly similar across these three countries, were that racial minorities were covered in stereotypical and damaging ways.

The media doesn’t accurately represent Black people. In general, they always show Black people in situations of violence, when Black men are violent and Black women suffer, or they show Black people as poor or fragile. It’s always that way in the Brazilian media.

Maria (37, woman, Brazil)

Some people linked these failures to the lack of a representative workforce within newsrooms and especially in positions of power, although they also noted some improvements recently. Antoine (29, man, UK) said he thought news media are ‘doing more and more now’, but ‘if it’s still going to have the same decision-makers in the boardrooms and behind the scenes, then sometimes there’s only so much that those people on the front-line can actually do without actually having power to make changes’.

Among interviewees from India, concerns about inadequate or unfair coverage more frequently focused on particular religious groups or castes. These individuals underscored the tendency among some news outlets to promote divisive narratives about or between religious groups or to encourage caste prejudice. As Arshad (32, man, India) said, referring to growing conflict between Hindus and Muslims, ‘I feel like this has all happened because the media is pushing people into that direction’, noting how people who were at one time ‘the best of friends’ are increasingly and suddenly divided. ‘I feel that all this boils down to what we read, what we consume in terms of media, whether it’s online, or on WhatsApp, or on the mainstream.’

In Brazil, India, and the UK, many also expressed dissatisfaction about the lack of attention to class differences in particular. Farah (40, woman, India) mentioned that the media overemphasise celebrities’ stories and asked ‘What has the common man got to do with all this stuff if he doesn’t have a morsel to eat?’ Some interviewees more generally argued that the news media are biased towards elites and those with more fame or power, leaving out regular people and the issues most relevant to them.

What they need to do is to transmit more and more real news and talk more about everybody’s daily life about everything, everybody, all social classes, not just focus on politicians, [and the] famous, for example.

Gilberto (26, man, Brazil)

Geographic divides

Another area where representation was seen as lacking by many participants, especially in the UK and the US, concerned coverage of regional or local perspectives. There were some who suggested that the gaze of national news was excessively focused on domestic issues, overlooking important things happening in the rest of the world. Lucy (41, woman, UK), for example, missed a ‘more global perspective’ and found ‘BBC mainstream news, for example, to be very inward-looking, parochial’. But more typically when such issues arose, most maintained that national news eclipsed topics that were relevant on a local level.

I also would love community news. I feel like we are overshadowed by national news, but I want to know if my city has new bike initiatives, what’s going to be under construction and why.

Pamela (28, woman, US)

The link between representation of local interests and trust in news, however, was not always clear or direct. A focus on local news was often referenced as a reason for consuming a particular news source, but it didn’t always mean people were more trusting of such outlets. Ricardo (44, man, Brazil), for example, said he distrusted Globo, but said he watched its local news station everyday ‘because it’s the only channel with local news’.