In this piece

The human impact of the lack of diversity in Brazilian newsrooms

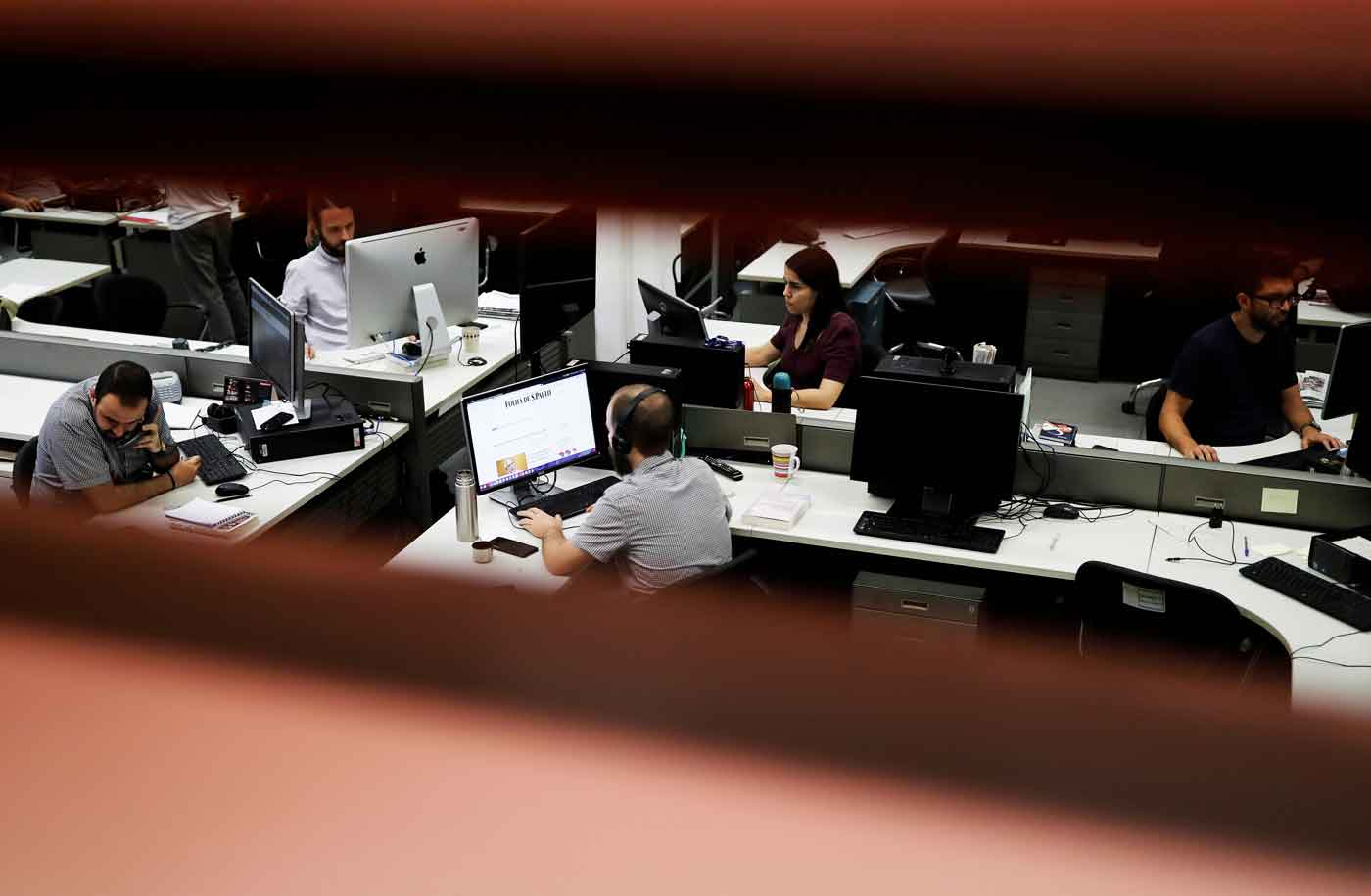

Journalists of Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, work inside the editorial office of the newspaper in Sao Paulo, Brazil October 31, 2018. REUTERS/Nacho Doce

In this piece

Human impactIn Brazil, where 43.2% of the population identifies as White, and 55.7% as Afro-Brazilian, newsrooms are still staffed by 77% White employees.

To measure the human impact of racial representation in Brazilian newsrooms, I created a questionnaire, asking basic biographical details and inviting journalists to indicate if they would like to talk further about their experiences.

I received 61 responses to my questionnaire, and conducted 32 long-form interviews in April 2022. The sample of 61 included 27 men and 34 women working for TV stations, radio stations, newspapers, websites and magazines – mostly as reporters, some freelancers and a few in management positions.

The racial breakdown included 52.5% White, 41% Afro-Brazilian, and 6.6% Yellow. Unfortunately, no Indigenous reporters responded to my query.

Two major themes emerged during interviews: the effect of a lack of diversity on news production, and the effect of a lack of diversity on the journalists themselves.

Production impact

We know from gatekeeping theory that newsrooms are mediators of information – filtering it through their own views and lived experiences. Employing editors and journalists from the same background will result in coverage reflective of what one demographic group thinks. My interviewees said:

Stuart Hall studied the effects of representation in media in The Spectacle of the ‘Other’: “Stereotyping reduces, essentializes, naturalises and fixes ‘difference’,” he wrote. This has been the subject of Brazilian-specific study for years: researcher Solange de Couceiro found: “journalists [...] are socialised in a way to [...] absorb, believe and defend the idea of racial democracy. Therefore, the manifestations of prejudice and racism that they transmit [...] act efficiently in the production of Brazilian racism.”

Journalists I spoke to felt that things could be different if there was more racially diversity in leadership positions:

My questionnaire asked journalists to record how many non-White editors they had worked for. The majority (57.1%) had never had one, 22.9% had worked for one, 14.3% had worked for two, and 5.7% had worked for three.

How did working for majority White editors materially impact the work of journalists in newsrooms? My interviewees reported:

My interviewees mentioned an impact of under-representation in newsrooms was the development of tokenism in assignments, wherein Afro-Brazilian journalists became responsible for all stories about race by default, because “they were the only ones there”. Speaking about coverage during the month of November, when Brazil marks Black Awareness Day on the 20th in honour of the death of Zumbi, journalists told me:

Human impact

“It is frustrating to work in an environment with mostly White people.” You won't be surprised to read that one of my interviewees said this. You might be surprised that the interviewee who said it was White. Yes, the human impact of under-representation affects White journalists, too. Although the impact I recorded on Afro-Brazilians and Yellow people was far beyond mere frustration.

Interviewees related stories about micro-aggressions and limited access that had far-reaching mental health impacts.

Comments about physical appearance, and specifically about the hair of Afro-Brazilians, were shared with me repeatedly:

“When I decided to braid my hair I became the joke of the newsroom. Even my boss was comfortable saying things like ‘here comes the real negro’, and everybody laughed. They never respected me.”

Another frequent issue related was that they were mistaken for someone that worked as a janitor or driver for the company, not as journalists.

feel humiliated when my colleagues are not capable of seeing me as equal to them.”

This happens inside the workplace and outside, when they are reporting.

My interviewees spoke frequently of the impact of working in a predominantly White space. The concept of “Predominantly White Institutions” (PWIs) was coined to describe the institutions in the United States whose histories, policies, practices, and ideologies centre whiteness. PWIs, by design, tend to marginalise the identities, perspectives, and practices of people of colour.

These “looks” and comments can be classified as “microaggressions”: a term coined by African American psychiatrist Chester Pierce to describe the relationship between black and white interactions. “Microaggressions are brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults toward people who are not classified within the ‘normative’ standard. Perpetrators of microaggressions are often unaware that they engage in such communications when they interact with people who differ from themselves.”

Ruchika Tulshyan, writing in the Harvard Business Review, said the term fails to capture the “emotional and material effects or how it impacts [...] career progression”. She added: “Experiencing what we know as microaggressions can be just as harmful, if not more, than more overt forms of racism.”

My interviewees also spoke of struggling to develop a sense of belonging in the workplace. One of my interviewees put it this way:

In the article A Question of Belonging: Race, Social Fit, and Achievement by Gregory Walton and Geoffrey Cohen (2007), they write: “One of the most important questions that people ask themselves in deciding to enter, continue, or abandon a pursuit is, “Do I belong?” Among socially stigmatised individuals, this question may be visited and revisited. Stigmatisation can create a global uncertainty about the quality of one’s social bonds in academic and professional domains — a state of belonging uncertainty. As a consequence, events that threaten one’s social connectedness, although seen as minor by other individuals, can have big effects on the motivation of those contending with a threatened social identity.”

I have highlighted “big effect on motivation” because this, to me, is key. Some of those I interviewed had given up working in newsrooms because they didn’t feel represented there and had no hope the scenario would change.

In her paper Journalists and mental health (2019) Natalee Seely notes that traditional newsroom culture encourages journalists to “check their feelings at the door”. In the Brazilian context, marginalised journalists do not discuss the impact of under-representation with their colleagues. But speaking to me off-the-record, several mentioned depression, anxiety, and even suicidal ideation.

Are media outlets aware that 98% of Black and Brown-identifying journalists surveyed for the Racial Profile of the Brazilian Press felt they face more difficulties in their careers than their white colleagues? If so, what are they doing about it?

Download the full paper for interviews and analysis of what’s been tried at the three biggest newspapers in Brazil: O Globo, Estadão and Folha de S. Paulo.

In summary, I came away with the impression that journalists are not best-suited to leading this sort of change. Instead, there are diversity and inclusion specialists that can be hired to guide newsrooms.

In the words of 2017 MacArthur fellow, Nikole Hannah-Jones: “If newsroom managers wanted diverse newsrooms, they’d have diverse newsrooms.”