How deep listening can make you a better journalist

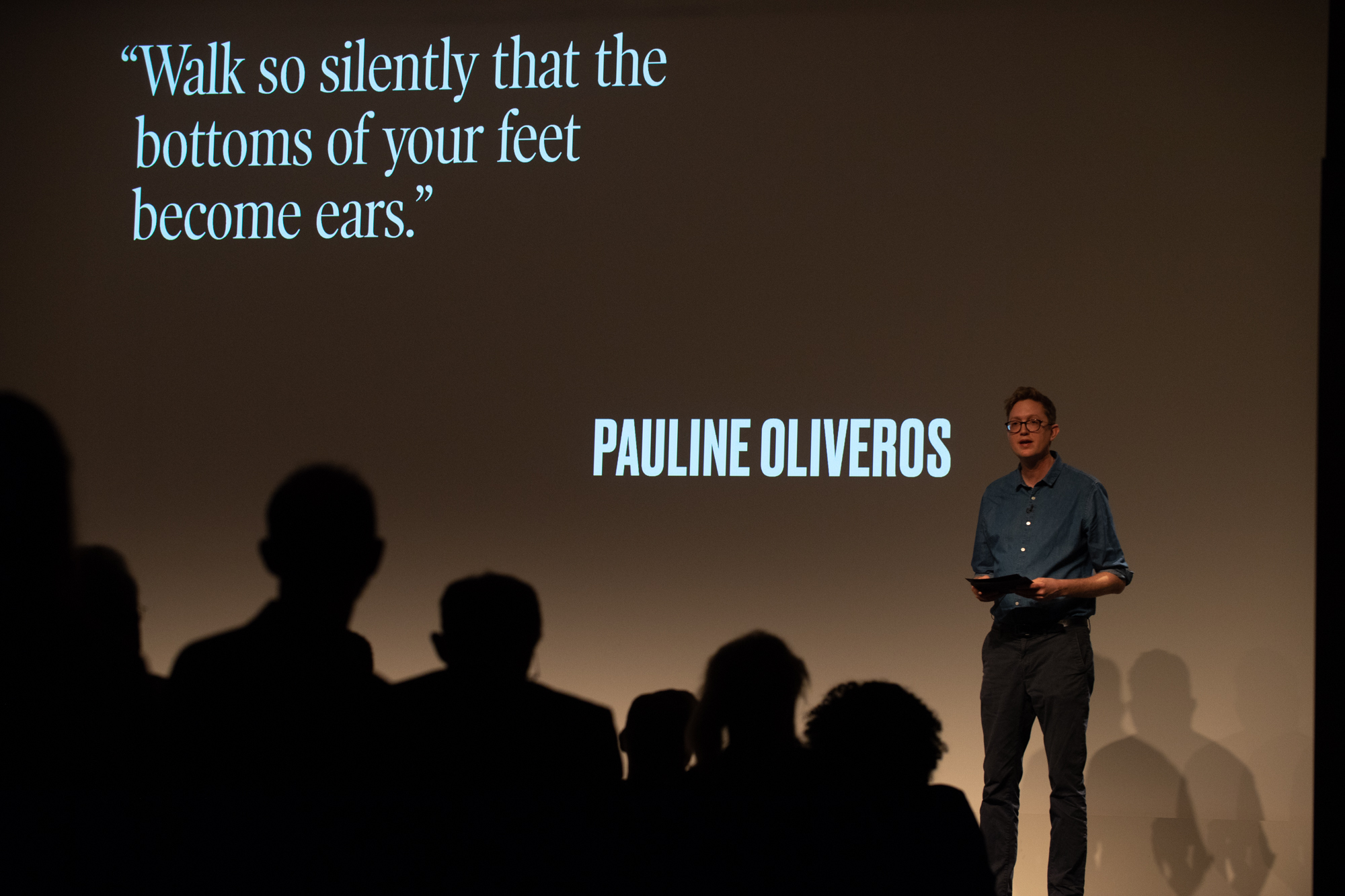

Daniel J. Clarke during his talk in December in London.

This is a transcript of Daniel Clarke's talk during the live journalism show we organised in London in December. You can find our Journalist Fellows' talks in this link.

‘Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears’ – Pauline Oliveros

This is not the usual instruction I would give to a correspondent when commissioning them for the BBC’s Newsnight, where I work as Deputy Editor. In fact, if I was to talk like that in the office, people would think I’d gone mad. But this quote from American composer Pauline Oliveros is one of the things that has recently made me think about journalism in a different way.

I’m going to take you through my journey into her world of deep listening, where it led me, and why I think it should inspire us day to day.

I first came across Oliveros’s work in June 2019 at a conference in Berlin called Engagement Explained Live. Everyone there was part of what’s become known as the ‘engaged journalism’ movement. They were interested in working out how to allow the public to participate much more deeply in the journalistic process.

I’d come along, among other reasons, because I was frustrated with the typical portrayal of the public in news pieces —five second vox-pops, weighed out for balance, and cobbled together after a few hours spent in a town on a fast train from London. Surely there had to be a better way of understanding opinions and experiences from the ground up. Maybe the answer was in Berlin.

I ended up in a workshop entitled ‘deep listening’. It sounded interesting, if slightly pretentious.

But the journalist running it, a man called Cole Goins, was terrific. He told us he was inspired by Pauline Oliveros, the American composer who coined the phrase deep listening in the 1980’s. She was a radical, and a pioneer in the development of electronic music. Above all, she was obsessed with what it means to use your ears properly.

Listening, she argued, is the basis of all culture. And the best deep listeners of all? Babies.

Here’s a quote: "Think of the tremendous acts of attention and concentration that babies make to explore sounds and speak their first words, to learn language and communicate through listening."

Oliveros believed that adults needed to train themselves to listen like that. She thought deep listening would open us up to interact better with others and, crucially, she saw deep listening as a starting point for doing something. As she put it, “listening is directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting and deciding on action.”

Cole Goins, the journalist leading the workshop, drew on Oliveros’s work to make a convincing argument that ‘deep listening’ was of serious value for journalists too. A better culture of listening could, for example, help break down barriers between journalists and those who don’t trust us. It could help us understand marginalised parts of the population, and those who feel alienated or bored by news coverage.

Taken by surprise

Like a lot of people, I first got interested in what we could do to understand our own country better in the wake of the EU referendum result in the summer of 2016.

Journalists throughout the world made similar observations after the election of Trump in the US, the rise of populist parties in Europe, and the victory of Bolsonaro in Brazil. That we as journalists were surprised by many of these events made it crystal clear that we had put too much trust in the tools and the stories of the political class, rather than trying ourselves to listen deeply to what was really going on.

The UK remains a country of profound geographic, political, and economic divisions, as the recent general election reminded us. We know that many people, particularly outside of London and among minority ethnic groups, feel unheard and disconnected from the world portrayed by mainstream news media.

These audiences told Ofcom in a recent report that they want to see a deeper understanding of their communities from the BBC by people with more knowledge of them. Without a doubt, we need much more diversity of all kinds within every newsroom. But would deeper listening also help?

I wanted to find out who was trying to listen more deeply to the public —especially to those who feel unheard by journalists— and whether it was leading to any ‘action’, as Pauline Oliveros put it.

Lessons from Sweden

So this autumn, during my time as Journalist Fellow at the Reuters Institute, I did some research. I came to realise that, around the world, there are journalists working to "expand the demographics of people media is listening to," as the academic Andrea Wenzel has put it.

In the US, I studied brilliant projects like City Bureau in Chicago. In the UK, I focused on operations built around better listening, from The Bristol Cable and the Bureau Local, to Tortoise Media. There are many others I could mention. But the example I want to explain now comes from another public service broadcaster.

In the aftermath of a British general election that has put the relationship between politicians and broadcasters under very public strain, deep listening opens up a different way of covering politics. A way that really does let the public set the agenda.

Swedish Radio is Sweden’s public service radio network. In the wake of Trump, Brexit, and some big shifts in Sweden’s own political landscape, they wanted to understand how lived experiences across the whole country were shaping events. They came up with an idea that turned the conventional news-gathering approach on its head They called it The Ten Million because Sweden had just hit ten million inhabitants.

Snow was falling outside Swedish Radio’s Stockholm offices when they invited me there in early December. Inside, project leader Helena Geige told me that the starting point for the project in 2017 was "to get out there and listen to people, especially in blank spots where we don’t normally go."

Working with their network of 25 local stations, they commissioned presenters and reporters to find people who they wouldn’t usually talk to, and to ask them two simple questions:

- What are you concerned about?

- What are the big issues in your lives?

It’s not as easy as it sounds. “It’s one of the hardest things to do as a journalist,” Geige told me. “Normally you have an angle… you have decided what to talk about… and then you get reactions, wanting people to say things that fit into our stories. Which makes stories boring and predictable.’

The next bit is really important: Swedish Radio weren’t interested in opinions —this was defiantly not a series of vox pops. They were interested in stories.

Swedish Radio recorded more than 500 individual stories —from pensioners who couldn’t afford to travel to see their children to dinner ladies worried about food waste in schools. All were told in their own words.

Swedish Radio didn’t just run these stories as individual vignettes. Instead, they used them as starting points for investigation and analysis. The project really took off when an election was called in 2018 because Swedish Radio built an agenda around these people. They used their stories and experiences to frame debates, and to shape interviews with politicians. Stories gathered locally, but aired nationally.

One of those stories featured Inga Karin. She told Swedish Radio that her pension was so low that she couldn’t afford to visit her children. Was her experience typical? What policy issues did it raise? And who, if anyone, should be held accountable? Inga Karin’s story ended up on the front of all the papers, forcing the Prime Minister to phone her directly.

The Swedish project was a real success, and won a major award. So what was it that really struck a chord?Daniel Varjo, one of the reporters involved, said something to me that really stuck: “People now think that media and politics are the same —that we’re the elite. That we don’t represent what people think. This was a very smart project because it worked against this idea. It said: ‘We’ll listen to you.’"

From Sweden to Mixenden

I couldn’t look into all of this without getting out there myself. So earlier this month I went with Sally Chesworth, a Newsnight colleague based in the North West, to meet some people in Salford, in Rochdale, and also in Mixenden, a village on the outskirts of Halifax.

Inside Mixenden library, James, the librarian, gathered together a small group of local people, from school-aged kids to pensioners. I asked some basic, open questions, and listened, as they told us about the challenges of life with no home internet. They told me how hard it is to navigate the machinery of the state when you don’t have a smartphone —or the money to pay for a phone call at all— and the state assumes that you do. They also told me about their frustration at having perceptions of your community shaped too often by negative, inaccurate portrayals by journalists and others.

As I sat in the library with this group of people, something from the deep listening workshop in Berlin drifted into my mind. It was the following sentence: “If journalists truly listened to the communities we serve, we could break away from narratives that are repeated over and over again - and get into nuance.”

When I was sitting in Mixenden Library, I felt that I was finally starting to get somewhere. I was hearing stories that we hadn’t done before.

What will travel with me from Mixenden, Stockholm and the other research I’ve done this Autumn? Many things. But the most important one is this: we need to open ourselves up to a broader, ground-up set of stories and perspectives from across the country by listening more deeply, and directing attention to what is heard.