Trust Conference 2023: seven things we learnt about press freedom around the world

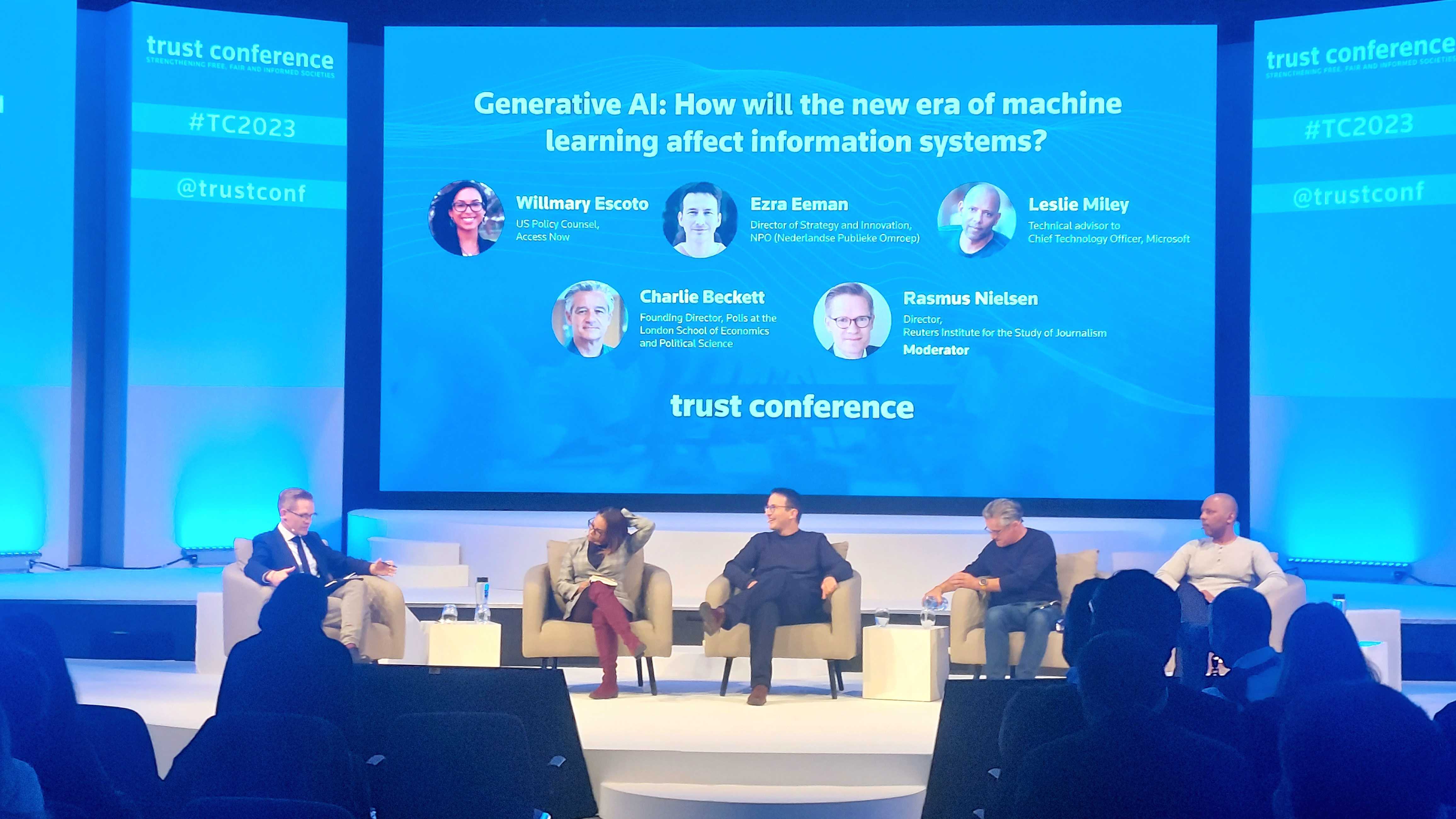

The generative AI panel on stage at TRF's Trust Conference 2023.

On 19 October, hundreds of delegates congregated once more in central London for the Trust Conference, an annual event organised by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Speakers included journalists, media workers, lawyers and human rights advocates such as Sebastien Lai, Jodie Ginsberg, Charlie Beckett, Rana Rahimpour and our Director Rasmus Nielsen. Here are seven takeaways from the conference on the situation of journalism worldwide.

1. Paying tribute to a journalist recently lost

In his introductory remarks, Thomson Reuters Foundation CEO Antonio Zappulla paid tribute to Issam Abdallah and reiterated calls for a fair and transparent investigation into the Reuters journalist’s killing on the Israel-Lebanon border by a missile from the direction of Israel. Abdallah was remembered again later on in the day during a panel session focusing on frontline journalism and featuring the winners of this year’s Kurt Schork Awards, which ‘honour the work of freelance journalists, local reporters and news fixers in developing countries or nations in transition’. A minute’s silence was held then for Abdallah and other journalists killed on the job.

2. Legal attacks against journalists are becoming more creative

Carolina Henriquez-Schmitz, director of TrustLaw, the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s global pro bono legal service, discussed the findings of a report about legal attacks on media freedom by TRF and Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

There has been an increase in the use of legal tools to stop journalists from reporting, she said, emphasising that this is a problem in all countries, including democracies.

⚖️ The rule of law is a precious resource for reporters at risk, but its growing misuse is pushing them into the firing line.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

At #TC2023, our TrustLaw Director @C_H_Schmitz showcased our research with @TowCenter, mapping the rise of legal threats stifling journalism. ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/4BBnOhFliL

She gave some examples of legal intimidation and repression tactics that are being used against journalists. One trend is that states are increasingly using ‘catch-all’ laws to prosecute journalists. These are loosely worded with ‘overly broad language’ and often carry severe penalties. Examples are Russia’s war censorship law, Hong Kong’s national security law, and Turkey’s misinformation law.

This is one example of how governments are getting creative in their tactics to persecute and silence the press, in some cases moving away from ‘traditional’ legal means such as defamation suits.

Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC, the barrister representing jailed Hong Kong journalist and Apple News founder Jimmy Lai, as well as his son Sebastien Lai, reiterated this point in a panel on protecting journalists against lawfare - a term used to mean legal attacks. “This new trend of law being used in a creative way to try to silence the journalists and also to slur the messenger is a new thing we’re seeing,” she said.

? When the rule of law is weaponised against those it should protect, it stifles critical reporting.@DoughtyStreet’s @caoilfhionnanna shared how we can strengthen legal responses and leverage international law, in places where rule of law has failed internally. ⬇️ #TC2023 pic.twitter.com/cscZw97Xw9

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

“We’re also increasingly seeing journalists targeted in a way that suggests they’re untrustworthy,” Gallagher said. This involves accusing journalists of other crimes like money laundering or theft, as is the case with imprisoned Guatemalan journalist José Ruben Zamora.

Journalists themselves are also not the only ones targeted. Authorities also sometimes go after journalists’ lawyers and family members. For example, four of Zamora’s lawyers have been jailed. “While this is outrageous, it is not exceptional,” Henriquez-Schmitz said.

Often, ‘lawfare’ involves multiple charges or lawsuits against a single journalist. “It’s like legal whack-a-mole because you’re often fighting a war on different fronts,” Gallagher said.

However, creativity can also help in defending journalists against lawfare, as lawyer Dario Milo illustrated with an example of an anti-SLAPP defence that legal experts developed in South Africa. “The enemies of media freedom are creative, so we must get creative too,” Gallagher said.

? Cross-sector coordination between NGOs, donors and governments can help the media fight back.@USAID’s @laurenseyfried shared the role governments can play in addressing these attacks and finding effective solutions. ⬇️ #TC2023 pic.twitter.com/UkoUbYm9vp

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

3. Journalists shouldn’t have to be heroes

In a panel on journalism in exile, Russian journalist Roman Aleksandrovich Anin shared his thought process when he decided to leave Russia. “I realised that my desire to go back was selfish - I wanted to prove that I was ‘brave’,” he said. “In my case, it was about being efficient, will I be efficient if I’m in prison? Of course not. Will my colleagues be efficient if they’re writing stories about me in prison? Also not.”

Speaking about the challenges inherent in reporting from a different country and dealing with state censorship, he added: “You have to be creative. It doesn’t matter if you come from a newspaper, if YouTube is the platform you can use, you have to become a video reporter.”

? The threat of harassment, imprisonment, violence and even death is pushing scores of journalists into exile every year.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

During this #TC2023 panel on journalism in exile, journalist Roman Anin shared the psychological and physical obstacles facing those forced to flee. ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/kJQEO6LSrT

Iranian-British journalist Rana Rahimpour shared distressing details of harassment against her by the Iranian government, including the wiretapping of her conversations with her parents, and threats against her and her family: “You reach a point where you feel, this is my choice to be a journalist, but it’s not my children’s choice, it’s not my husband’s choice,” she said, as she explained her decision to leave the BBC.

In her case, and in that of her colleagues at the BBC Persian service, physically not being in Iran doesn’t mean the Iranian state feels far away, especially in light of the news of credible threats by the state against individuals in the UK. Moreover, Rahimpour and a lot of her former colleagues still have family members in Iran who could face repercussions for their reporting. “The fear is day to day and we feel it in every decision we make [as Iranian journalists based] in London,” she said.

? A new generation of Iranian journalists have fled into exile in a bid to escape further persecution.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

During #TC2023, Iranian-British journalist @ranarahimpour explored the ongoing impacts experienced by families of exiled reporters, and the reporters themselves. ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/EIXhO4YdNN

Rahimpour also paid tribute to the journalists who have chosen to stay in Iran, often facing imprisonment. “Without journalists in the country, those of us outside have nothing to report.” Among the journalists she mentioned are Elaheh Mohammadi and Niloufar Hamedi, who first reported on Mahsa Amini’s death at the hands of Iran’s ‘morality police’ last year.

Cinthia Membreño, Audience Loyalty Manager for the Nicaraguan weekly Confidencial, painted a bleak picture of the situation for journalists in Nicaragua. “Even the drivers, even people who drive you to your field, they are targeted, they go to jail,” she said.

For the growing community of Nicaraguan journalists in exile, there are additional challenges that come with their situation. “There is a growing conversation about [psychological help] because journalists realised they can’t do it all themselves, they’re not heroes,” Membreño said.

What’s happening in Nicaragua mirrors patterns elsewhere across the world. “It’s like there’s a script. When you look at Russia, at Belarus, you know what the next phase is,” Membreño added.

Jodie Ginsberg, president of the Committee to Protect Journalists, reiterated that she’s seeing a disturbing pattern across the globe when it comes to press freedom. “Because we’re seeing a decline in democracy, when that happens, often the first people who are targeted are journalists,” she said.

4. Simple digital hygiene practices are important

In a panel on cyber risks to journalists, Salvadoran reporter Ricardo Avelar shared his experience of finding out he’d been spied on with Pegasus software: “When you tell your sources, everything we’ve talked about, every meeting we’ve had, every picture you’ve sent me, they know, what happens is they stop talking to you.”

While Pegasus is headline-grabbing, and a real risk to journalists as Avelar shared, Citizen Lab senior researcher John Scott-Railton stressed there are many other, more common cyber threats as well.

? Journalists and newsrooms are in the firing line of growing cyber threats aimed at crippling their work.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

During our #TC2023 session, @citizenlab’s @jsrailton explored the use of methods used to target reporters, such as hacking and leaking against them. ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/jsUzrSTe2W

James Stewart, Director of Communications at the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre, reiterated this point, saying: “We see quite a lot of ransomware cases that could have been prevented by pretty basic cyber hygiene.”

Scott-Railton added, “It’s important to think of ourselves as having agency.”

Both Stewart and Scott-Railton stressed that there are many simple digital security practices journalists can put in place to protect themselves, some as simple as having secure passwords, enabling multi-factor authentication and keeping devices up to date.

? Ransomware and phishing attacks are targeting media outlets in a bid to obstruct truth-telling.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

During our #TC2023 session, James Stewart from the National Cyber Security Centre outlined the steps media outlets can take to protect themselves against these attacks. ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/RLZvaMRGEa

5. Generative AI does pose some risks to journalism

In a panel about generative AI moderated by our director Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Willmary Escoto, US Policy Counsel for the non-profit Access Now, pointed out that the conversation around the risks posed by AI is very future-focused and often doesn’t recognise the dangers we’re currently facing. “These risks posed by AI are not theoretical, they’re happening,” she said. Among these “very real, heartbreaking harms” are employee monitoring systems and facial recognition, as well as “the risk posed by the perpetuation of bias and discrimination by these systems,” she said.

To confront these issues, Leslie Miley, technical advisor to the Chief Technology Officer at Microsoft, said: "We cannot be afraid of regulation. We have to understand that it is what is going to help us develop this even further than we already are."

6. However, these risks are not likely to be existential

The big-picture, apocalyptic fears around generative AI are unlikely to materialise, the panellists said. Ezra Eeman, Strategy Director at Dutch public broadcaster NPO, said that "trust is partially based on the connection with the human making the content." When you lose the human involved, you lose the trust, he added, suggesting humans will remain involved in processes involving generative AI, at least in his outlet.

Charlie Beckett, Founding Director of Polis at the London School of Economics and Political Science, said that "the difference with generative AI [from traditional AI] is that everyone can, and is, playing with it. But some people do stupid things with it."

However, generative AI shouldn’t be treated completely differently from other tools journalists use. "The job of a journalist is to check things, to check your sources, to verify things, to use your human judgement," he explained.

"Journalism's been facing existential threats for decades, and often these threats aren't about tech," Beckett concluded, pointing to some of the other press freedom issues addressed by the conference, such as governments hostile to journalists.

? Generative AI tools have taken the world by storm. But how should newsrooms approach this technology?@LSE’s @CharlieBeckett shared more on potential impacts that news organisations should be aware of, and how they can adapt to deal with potential risks. ⬇️ #TC2023 pic.twitter.com/5rPZzWTRQF

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

7. Frontline journalism is dangerous and sometimes frustrating, but invaluable as a testimony to tragedy

The final panel discussion of the day featured two winners of this year’s Kurt Schork awards: Asami Terajima, a reporter for the Kyiv Independent, and Léa Polverini, a freelance journalist. They shared their experiences reporting on the Ukrainian frontlines and the labour camps in the Chinese region of Xinjiang, respectively, in conversation with New York Times international correspondent Matthew Mpoké Bigg and Sky News presenter and podcast host Niall Paterson.

"My job as a journalist is to show the harsh reality" of soldiers' experiences on Ukrainian frontlines, Terajima said, explaining that sometimes this goes against the narrative put out by Ukrainian authorities.

Reporting from soldiers’ positions in Donbas is also physically dangerous and emotionally taxing. "You have to be comfortable with the idea that you might not know what's going to happen to you," she said. "If you start to think deeply about everything or if you start to process everything you see and hear, it would be very difficult emotionally," she added.

? Japanese journalist @AsamiTerajima won this year’s #KurtSchork Local Reporter Award.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

At #TC2023, she shared her experience of witnessing and reporting on the full-scale invasion of Ukraine as a reporter who grew up in the country. ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/nx5hmrf4Ab

Polverini’s reporting also challenged official narratives, and in her case, her job was made particularly difficult by the circumstances faced by her interviewees, as well as by the fact that she was unable to be in Xinjiang, also known as East Turkestan, and so was reporting from the border with Kazakhstan. “You know when you do this job that you won't have results in a few days or few weeks or few months but it takes longer," she said, explaining she’s documenting crimes for future accountability.

? French journalist @polvrini won this year’s #KurtSchork Freelance Award.

— trust conference (@trustconf) October 19, 2023

At #TC2023, she discussed the challenges of interviewing survivors of Chinese labour camps in Xinjiang, and ways to ensure and secure their trust. ⬇️#TC2023 pic.twitter.com/nvYQt5uxJg

"We keep doing it because otherwise, who will do this job? It's a question of justice and accountability," she said.