Moving the needle: How the ‘New York Times’ guided readers through America’s most uncertain election

Kamala Harris and Michelle Obama at a campaign event in Kalamazoo, Michigan. REUTERS/Evelyn Hockstein

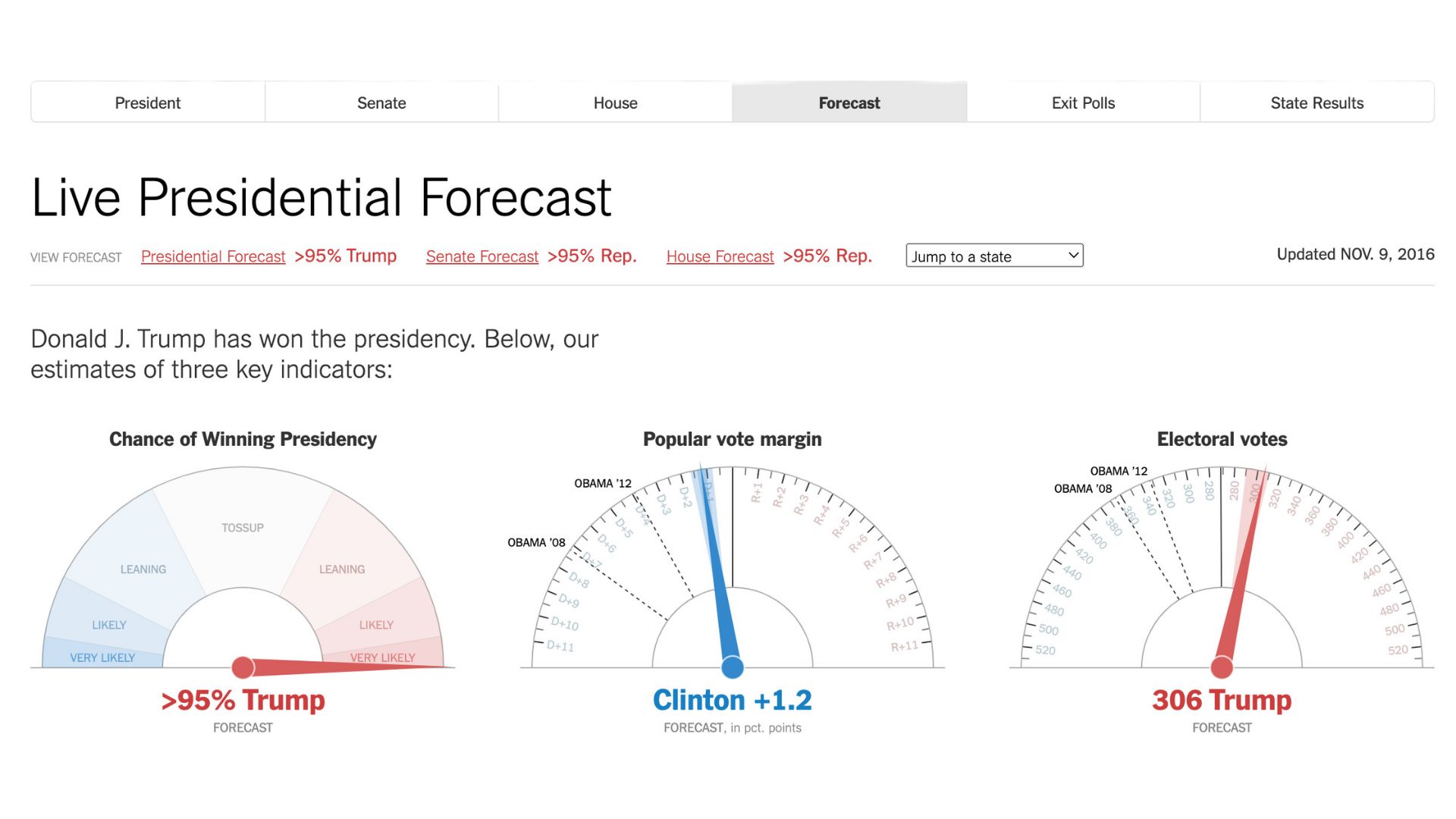

On the night of the 2016 US presidential election the New York Times launched the needle, a data visualisation vaguely reminiscent of a car’s speedometer. The needle promised to show readers what the early count may mean for the final result. As election night progressed, millions of Americans stared at the needle turning with curiosity, trepidation, anxiety or utter horror. The Times’ needle suggested a Donald Trump victory was likely hours before the AP called the race for him.

The idea behind the needle is simple, according to deputy Graphics editor Wilson Andrews, who’s led the Times’ election results operations since 2016 and with whom I spoke for this piece.

“We start with a pre-election expectation of how the vote might play out in every part of the country, whether at county level or at precinct level,” he said. “Then we make an estimate based on polls and historical results, and on the demographics of these areas. Our goal is to set a benchmark for where we think the election might end up in that particular place.”

That’s what the needle starts the night with. And, if turned on before enough votes are counted in a place, the needle’s forecast would be based on the pre-election estimate. But once the model starts getting votes, it quickly learns more about how the election is actually playing out and that’s what will move the needle on election night.

If a candidate is outperforming the needle’s expectations in a certain county, for example, that might mean that they’re going to outperform them in similar counties. So the model is processing all these insights in real time and that’s why the needle moves one way or the other.

“That’s what the model is doing,” Andrews said. “Moving over the night from a pre-election estimate to an in-between modelled estimate that takes into account the votes we have so far and what we think of those that remain to be counted.”

Will there be more than one needle?

The election needle has gone through several iterations since its momentous debut in 2016. Four years ago, in a race with a record number of absentee ballots, the Times didn’t publish a national model and only ran needles for three states that provided their data in a detailed fashion: Georgia, Florida and North Carolina, Andrews’ home state.

This time Andrews and his team are still pondering how many needles they’ll deploy on election night. Ideally they’d like to forecast the presidential race and include seven more needles, one for each of the seven swing states. But they are still working towards this goal. Meeting it will depend on the kind of data that is available on election night.

“Every state and every county has its own way of doing things and we have to grapple with this well,” Andrews said. “We will only publish the forecast when we are confident that it can be a reliable source of information for readers. We don’t do it just because people expect the needle. We do it because we have enough data to feel confident that our estimates will be a helpful guide on election night.”

What’s different in 2024?

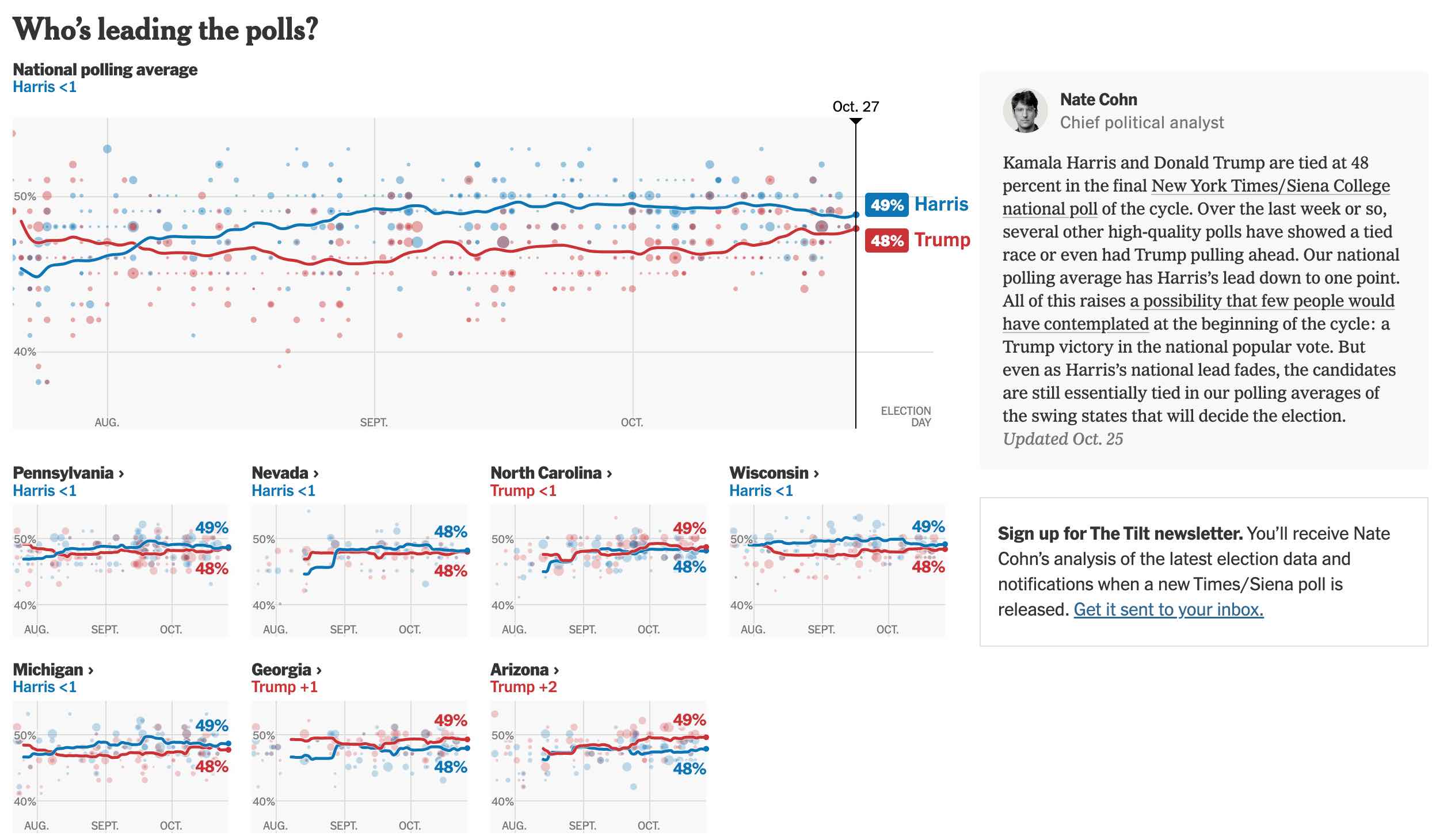

The polls suggest this year’s presidential race is as close as it gets, and this is the most important issue Andrews and his team are grappling with as they turn into the home stretch.

The Times’ own polling page is intentionally structured in a way that emphasises that the election could go either way.

“We wanted to make sure that we were showing that the polls are not perfect, and that they often miss the results,” Andrews said. “We’ve also embedded reporter modules next to these graphics to make sure that people are understanding them. We want to make sure that they know how to think (and how not to think) about the polls. We want them to know that polls are useful but not infallible.”

Joe Biden wasn’t declared the winner in 2020 until four days after election day. This year’s race looks even tighter and the Times’ team is preparing for a coverage that could extend well beyond election night.

“2020 taught us a lot about how to cover an election that takes more than one night to resolve,” Andrews said. “So we are preparing to cover 2024 as an election week, rather than as an election night, and we are investing in tools that let us explain the vote in a more direct way than we have in the past.”

Election results pages tend to be dashboard-centric displays of data. They often include live-updating information, but not much context and analysis. The Times is aiming to change this by injecting insights from experts in real time.

The key word is context. “We’ll be telling the reader what data we think we’ll get in a specific state, and in what order,” Andrews said. “We’ll also update our model in real time so they can feel like they’re getting a guide. Cable news has traditionally done this very well, and we want to do better at holding people’s hand as the vote count progresses.”

Andrew says his team is working on making the needle work beyond election night as a way to warn readers: “It’s our way to tell them: ‘Yes, the vote count early looks like this in a swing state, but you should probably take that with a grain of salt, because we know that the reported vote might skew one way or the other.’ That's the main message that we are trying to frame the reported results around.”

What is the needle based on?

More than 60 people are contributing to the forecast that will power the needle on election night. The team includes traditional reporters, statisticians, software engineers, and the designers and graphics editors who are building the frontend displays. They’ve been working on the data powering the needle for the last two years and their work takes a lot more reporting than people may think.

“It means building strong relationships with election officials to know exactly what kind of votes they expect to count and when, and doing programmatic and manual reporting to get that data beyond what we get from the Associated Press,” Andrews said. The goal is to enrich this data with other sources, including the Times’ own Siena poll, with more details about who’s voting and how they are voting.

The needle’s model is not only powered by data sets and data wizards but also by the work of dozens of reporters on the ground in the states deciding the election.

“There’s a good amount of shoe-leather reporting, both before election day and after, that contributes to us doing this well,” Andrews said. “That’s the kind of reporting that we hope to bring directly to readers to help them understand what happens in places like Maricopa County or Philadelphia, especially after election night if the election is not called. Those places were really important in 2020.”

Will the 'Times' do any race calls?

Through the needle, the Times is aiming to publish a real-time model on how the race stands throughout election night. What it won’t do is call any races, something the Associated Press has done in every US election since 1848.

“It’s an important distinction,” Andrews said. “The needle's job is to help readers make sense of how the vote might end up. But we don’t use the needle as an explicit race-calling tool.” The Times relies primarily on the AP for those calls. But they pay closer attention to the race calls in the most competitive states and districts, and they decide on a case by case basis whether they publish those race calls.

A good example is what happened in Arizona in 2020. The Times was not comfortable with a race call because they didn’t think there was enough information to know if Trump or Biden would win. So they only called the race a few days after other outlets did.

“We want to make sure that we are accurate,” Andrews said. “Traditionally we have not been the first to call the result, and I don't think there is any internal pressure to be the first to do that. We want to get it right, and that’s our first priority.”

How is the 'Times' planning for the worst?

With so many state races in razor-thin margins, there is a real chance that one of the presidential candidates claims victory before all the votes are counted, presents the final result as fraudulent and tries to take power anyway. This makes the first hours of the vote count especially vulnerable to false narratives and makes it even more important to provide a nuanced account of what is happening in real time.

How is the Times planning to do this? “We are publishing pre-election guides [on counting patterns in each state] but also layering that into our results pages in terms of what readers can expect,” said Andrews. “We want to help people see that there’s still a vote count to be done and that it’s exactly what we expected, because the officials told us so. That’s reporting we’ve already done in every state to get a better understanding of how this time might be different from 2020.”

Not every state will be counting votes in the same way they did four years ago. Some might be slower and some might be faster, and this will be reflected in the forecast and in the results display.

Andrews said two factors could influence the time in which race will be called in each state. The first one is if the rules, which are set by politicians, allow the election officials to count ballots before election day. “The ones that do allow that tend to finish their count on election day and the others don’t,” he said. “These are the states that usually take a longer time. States like Pennsylvania, Arizona and Nevada took longer in 2020.

The other factor is if a race is very close. This is what happened in Georgia four years ago. They counted pretty quickly, but it was such a close race that all of the counties needed to make sure that they counted all of their votes before the race was called. “Even in some of states like North Carolina or Georgia, that typically count faster, we may need to wait until Thursday or Friday until a race is called,” Andrews said.

How will the 'Times' analyse the result?

The distinction between the election results display and election analysis is increasingly blurred, with the Times aiming to publish early analysis bits from reporters and data journalists in real time throughout election night.

“If you come to us on election night, not only will you see the live results, but you’ll also be seeing how certain types of counties are voting and what kind of shifts we are seeing in the presidential race from 2020,” said Andrews, who thinks this will be a helpful early tool for people who are trying to understand what’s going on.

This is the kind of analysis that will go into larger pieces over the course of the week, with journalists already thinking about what kind of questions they should try to answer first. and setting up data pipelines and tools that can help us answer those quickly.

Any advice for smaller newsrooms?

The Times will cover the US election with more resources than any other newsroom. So I asked Andrews what would be his advice to colleagues coordinating smaller teams in countries around the world.

“The most important thing anyone should know is not to take the early returns as indicative of where a race will end up,” he said. “Patience is a virtue for watching what happens, especially in the swing states. Checking against previous elections is a great way of getting an idea of where things might end up if certain large counties have not reported much of their data yet. But you have to be careful: 2020 may not be the best guide this time because states might report in a different fashion and be faster or slower than last time.”

How should journalists be framing the election for their readers? “They should stress that counting the votes might take a while, and that election night can become election week,” Andrews said. “In the 2022 midterm elections that was very much the case. The [party controlling the] House of Representatives wasn’t called for eight days, and something like that could certainly happen again.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time