This journalist wants you to try open-source AI: “AI is shiny, but value comes from the ideas people have to use it”

Florent Daudens speaking at a recent conference.

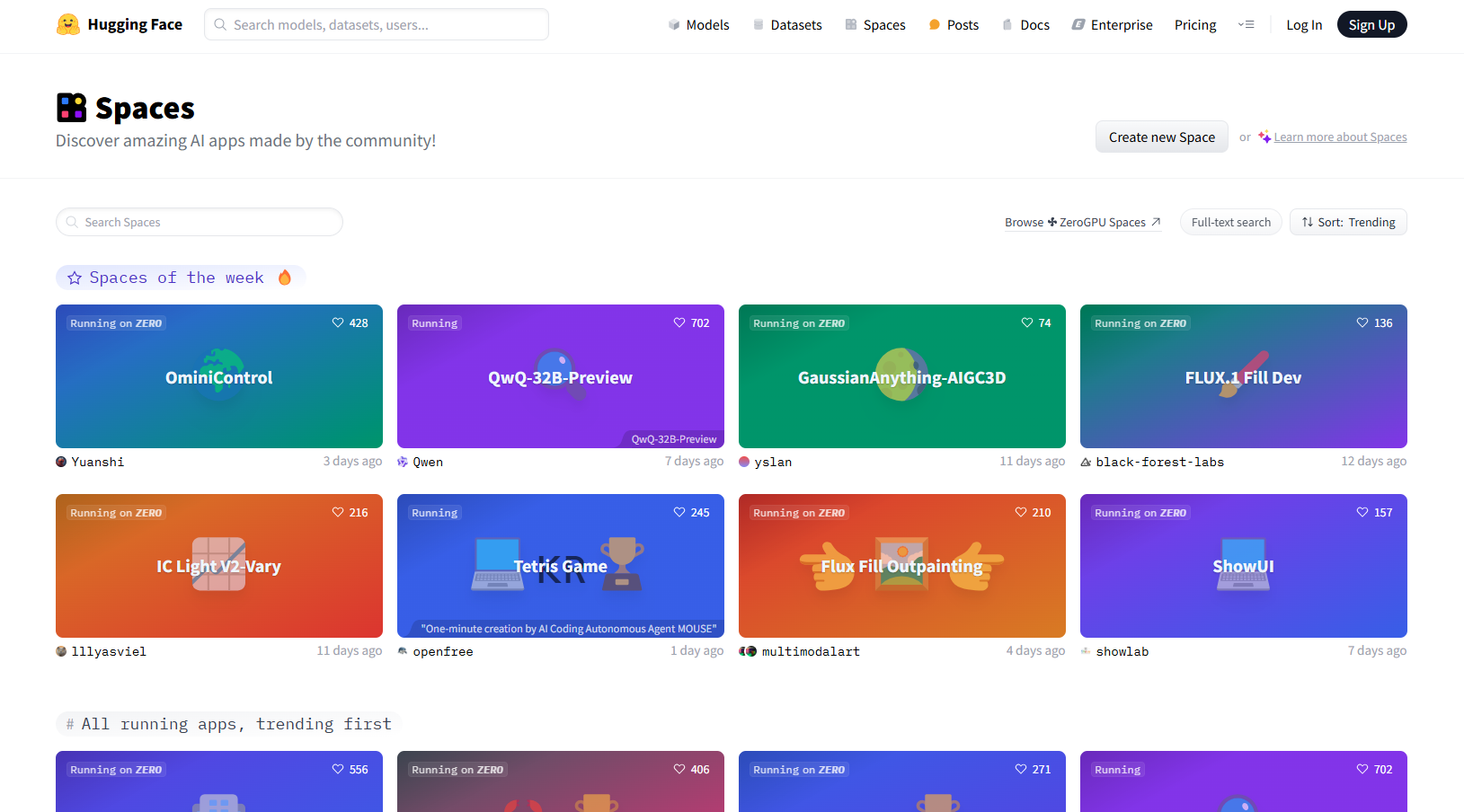

‘Open-source’ is becoming a buzzword for so many aspects of modern journalism, from citizen journalism to open-source intelligence journalism, also known as OSINT and pioneered by outlets like Storyful and Bellingcat. With generative AI entering the stage, some voices are beginning to talk about open-source AI. But what is open-source AI? And how can journalists benefit from it? At the forefront of those questions is Hugging Face.

Founded in 2016, Hugging Face is named after a popular emoji (?). Its original vision was to build chatbots. Since then, it has pivoted to a platform for AI collaboration and now hosts models and datasets for 50,000 organisations, according to Forbes.

Hugging Face is also accessible to individual users as a hub where they can experiment with, use and develop open-source AI models. They can organise themselves into communities that share models, datasets and tools. There’s a community for journalists too.

However, Hugging Face’s crowded interface and many models, datasets, and apps may be intimidating to a new user, especially for journalists with limited technical knowledge. As Hugging Face’s press lead, Florent Daudens’ mission is to try to change this. Daudens has been touring conferences and speaking to journalists and media workers to encourage them to try the company’s platform.

I spoke to Daudens and asked him about open-source AI, how journalists can benefit from using it, and how Hugging Face works. Our conversation was edited for style and brevity.

Q. How would you explain Hugging Face to an average journalist who doesn’t know what you do?

A. Hugging Face is the place where you can do collaborative AI. Big tech companies, researchers and individuals develop models there, improve and fine-tune foundational models for their own needs, and also work with a wide range of smaller and more task-oriented models.

Currently, the Hugging Face team is made up of around 250 people. We are heavily distributed around the world. Around 40% of our team is in Europe, a lot are in North America, and all around the globe. We are a team of researchers, but also ethicists. For example, Sasha Luccioni researches the impact of AI on the environment.

That’s the core team, but Hugging Face is mainly a community. We have five million users, and recently we crossed the mark of one million public models. We have around 250,000 data sets and 300,000 Spaces, which are apps based on the models. We used to describe Hugging Face as a public library of AI, but that doesn't convey a sense of the community. So I think ‘collaborative AI’ is a better way to explain what it is.

Q. How are you organised as a company?

A. We work in small clusters of teams. The teams on the science side, for example, work in small groups on very specific research aspects of AI. For example, this week we released SmolVLM, a vision-language model [an AI model which can process text and images simultaneously]. This is a very small model, under two billion parameters, but it punches above its weight because it can accomplish a lot of tasks thanks to the quality of data and the method. [In AI models, parameters are the internal variables the model uses to make decisions. The largest models have over a trillion parameters.]

We also have a society and ethics team. In Europe, we have Giada Pistilli, who is our principal ethicist. She's doing a lot of work on bias in models. We have Margaret Mitchell in the US, who is our chief ethics scientist. We're working on public policy, on the environment.

The hub is the technical part of the interface. It’s like a (gigantic) collaborative library where people can create, use, and download models, datasets, and Spaces while collaborating with others. We serve one billion daily requests and six petabytes of bandwidth each day, which is really consequential [one petabyte accounts for 1 million gigabytes].

Q. What does your job as press lead encompass and what made you want to get involved?

A. My colleague Brigitte Tousignant and I address all aspects of helping journalists understand what open-source AI is and connect them with the researchers. Since it's decentralised, researchers are strongly encouraged to communicate about what they are working on. This is not the traditional approach. It doesn't go through a lot of approvals. You can talk directly to researchers who are knowledgeable in their field.

The second aspect, given my background, is to help newsrooms and the journalism industry to make sense of AI and to be able to use Hugging Face. When I was in journalism, I worked on a lot of AI projects. Throughout my career, I've been a generalist journalist, I've specialised in social media and data visualisation, and then I've been a manager of newsrooms where sometimes I had to find new ways of surviving.

All of this gave me a sense of the importance of technology in journalism. I've always been the one with a technical edge in editorial companies. At a certain point, I felt the need to have a broader impact on the industry and the profession, and Hugging Face was a natural match.

I joined at the end of April, and since then, I have focused on building a community around open-source AI, developing useful tools and pieces of training, and lots of discussions and communicating on social media. I see my role as trying to help people make sense of it, but most importantly, to make an idea their own, rather than suffer from it.

Q. How does Hugging Face make money?

A. The core mission of Hugging Face is fighting the concentration of power in AI because it involves so much capital and so much computing power. It's important to have healthy competition in this field, especially because it's such a foundational technology that will create so much change in people’s daily lives.

We are focused on lowering the barrier of entry to AI, which means that the vast majority of what we do is on the free tier of usage. Retrieving and downloading models, for example, as well as uploading data sets is mostly free. Our business model is more focused on businesses. There are three main streams: the expert support programme, if you need some help from experts to develop your own AI infrastructure; the spaces hardware option if a company wants to build its own infrastructure; and the Enterprise Hub, a version of the Hugging Face hub for private development. This is for big teams that have several hundreds of AI developers.

We've been profitable in the last trimester. We are capitalised at $4.5 billion, and our investors are really diverse. This was important for the co-founders, French entrepreneurs Clément Delangue, Julien Chaumond and Thomas Wolf. Our vision is to be agnostic, and we are not controlled by a specific investor. Opening the capital to a whole wide array of investors gave us freedom and neutrality regarding what's happening in the AI space.

Q. What are some practical ways in which a newsroom can use Hugging Face?

A. The best place to start is with Spaces, because you'll see a lot of no-code solutions. One tool that is really useful for newsrooms is Whisper Web, a tool to transcribe interviews. It's based on an open-source model by Open AI, Whisper Turbo, which a team member, Joshua Lochner, adapted into a web browser version.

Our tool will download the weights on your computer, then you can cut your internet connection and transcribe your interviews on your device. This means that it's fully confidential and it doesn't cost you anything because it's running on your computer. It's the kind of tool you can use for a daily task and you can see an immediate impact on your work.

What I'm seeing right now is a lot of newsrooms becoming more and more aware of the possibilities of AI, but also a big tendency to use consumer products for journalism, which is problematic in several aspects. The first is that journalism is a specialisation, and you need specialised tools for your profession. For example, instead of using a big model for everything, which is the equivalent of using a sledgehammer to crack a nut, you should think: are there small, specific models for these tasks? And how can I fine-tune them with my own data?

For example, do you want to build a tool to help you improve your SEO? You could take the best headlines you wrote and train a model on them. This will help you come up with suggestions for new articles. It's not hard to fine-tune models, especially since we have tools that take away the hardest parts, such as Auto Train. You only have to choose a model and input your data, and it will give you a new, fine-tuned model, which you will own. Also in terms of environmental impact, it's important to think about how you use AI.

Q. Could you give us another example?

A. A lot of journalists work in Google Sheets, so I built a smaller plugin which allows you to call models on the hub in your Google Sheet. If you want to classify content for moderation or extract entities for an investigation, you can do it with this plugin. I've also seen interesting examples of data extraction from hand-written letters, such as with Qwen-VL. Gradually, you can see more and more advanced use of AI. The Washington Post recently decided to build a generative AI search feature. I've also seen some interesting investigations, for example, from the New York Times with models being used to find relevant content in several thousands of hours of Zoom meetings or to sift through social posts and extract information.

This is a shiny technology, but the value will come from the ideas people have to make use of it. This is especially important in newsrooms. How do you equip people to imagine the possibilities and the capacities of AI?

Q. What’s the best approach for a small newsroom that doesn't have a lot of resources in terms of time, money and people? How can they avoid being left behind?

A. One of the biggest revolutions of generative AI is that it allows you to talk to the machine with your own words. In small newsrooms, you rarely have a developer on your side. With generative AI, if you have an idea of a front-end user experience for your readers, you can ask the machine, in your own words, to give you the first iteration of the code.

Sometimes, you’re going to need to be a bit more technical and interact with your machine in a more complex way, but AI will help you with this. Another important thing is the importance of collaboration. I've seen this, especially in data visualisation: nobody developed all visualisations from scratch. We relied on libraries but also tutorials from people who were willing to share their expertise and some code snippets that we could reuse...

In a sense, it’s the same with AI: we can and should find ways to collaborate, exchange tools and start from already existing products. There's also a need to build stronger communities around journalism and AI so that people don't feel lonely because it can be intimidating and it's important to find some resources and a strong network to help you and build stuff with you.

Q. Which ethical principles should newsrooms consider when they're thinking about AI in the context of journalism?

A. The core values are openness, transparency, and accountability. For newsrooms, it's always a question of understanding how your model was built, on what data and what the biases are that could emerge from it. As Felix Simon recently argued, there is a need to be transparent with audiences when you use AI, but knowing how to do this is more complicated. The ‘human in the loop’ is important, but how is it compatible with the scaling possibilities of AI?

It’s also key to discuss how to make sure AI will increase the creativity and autonomy of people in their daily work, rather than making people feel deprived of their expertise. What are the key differentiators between humans and machines? In journalism, it comes down to two fundamental aspects: editorial judgment and curiosity. Journalism starts with people asking the most important questions about a specific topic.

Q. At Hugging Face, you have lots of users working on models and uploading data sets. How do you ensure that people are not infringing your terms of use? For example, how do you ensure the data sets you host don’t contain copyrighted data?

A. Our content policy is key to building a healthy community, and we developed it following our values ‘to advance open, collaborative, and responsible machine learning’. These guidelines address two categories of content: inappropriate content, which is removed from the platform, sometimes with further consequences for the user responsible; and moderated content. We do a lot of moderation to ensure the platform is safe in collaboration with concerned users. When moderating, we focus on the origin, handling and usage of the artefact in question.

In terms of policies, model cards are a really important one for us: we encourage each developer to be transparent. This is model and dataset documentation which includes details such as the developers, funding, licenses, source model identified biases, model training, evaluation and environmental impact.

The code of conduct is also an important part of how we build our community. We rely on a lot of community involvement. Users can flag content and collaborate with people to help them improve.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time