“I think removing content by Donald Trump will always have to meet a very high bar”

Richard Allan / Picture: Liberal Democrats

Richard Allan has spent most of his life working on issues related with politics and tech. He left Facebook at the end of 2019 after 10 years in various public policy roles. Before joining the company, he was a member of the UK Parliament for eight years and he was appointed to the House of Lords in 2010. Richard is now a Visiting Fellow at the Reuters Institute, where he’ll be studying the regulation of online services, with a particular focus on the interaction between politics and social media. I spoke to him recently about those issues. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

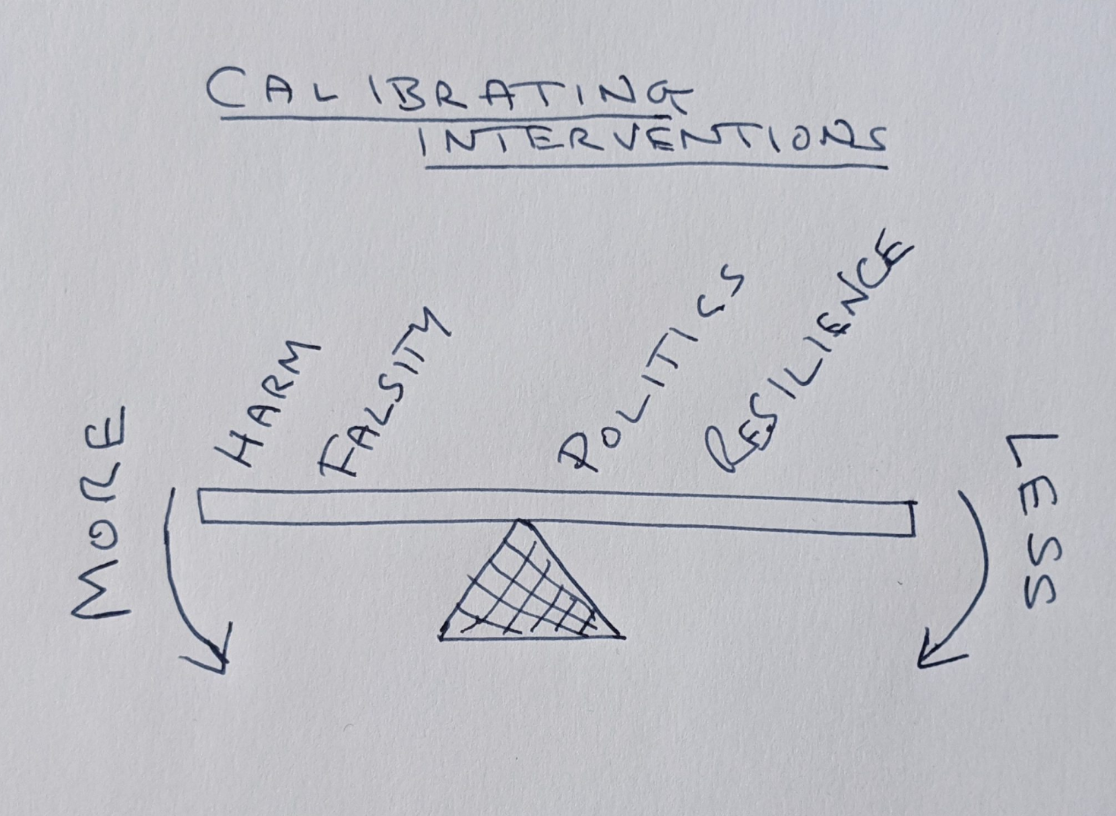

Q. On a recent blog post, you introduced an interesting framework that helps understand how Facebook and other tech companies make decisions around content. You use the metaphor of a weighing scale that turns towards or against intervention depending on four factors. Could you explain how it works?

A. Sure. The first two factors you should consider before removing content are harm and falsity. That’s usually where people start off: seeing it as a relatively simple problem solved by removing content that is harmful and content that is false. There’s certainly a very strong element of wanting to remove content that is harmful and there is a bar. If something is a direct call for violence –“Let’s go out tomorrow and beat up anyone that we see has got skin colour whatever”–, that’s clearly, immediately harmful.

But often, particularly when people put out misinformation, there are some other factors that kick in, and the other factors that I think help tip the balance the other way sometimes are the extent to which something has become a partisan political issue and also the extent to which people have resilience against that form of information. That may mean it’s just not necessary to act.

Most of us would say that platforms’ default position should not be censoring speech. They should be censoring speech only when they can prove that it’s necessary and proportionate. The example I would use is something like “the earth is flat”. It’s clearly false. As far as I’m aware, it doesn't cause any harm. And then, on the other side, it’s not political and there’s very high resilience: pretty much everyone knows that’s nonsense. So that means platforms don’t act, even though the content is clearly false.

Q. But not every example is as clear as that one.

A. No. And I’m trying to tease out the multiple factors in play. Take another example: “Barack Obama was not born in the United States”. It’s clearly false. But you actually have a whole load of these factors in play. It’s highly partisan and political and it's not necessarily directly harmful. It’s racist and it sort of undermines the authority of the state. But intervening is a much more complex equation for something like that.

Q. That makes perfect sense. However, I would like to talk a bit more about harm. Facebook has admitted that its platform was used to incite violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar. Do you think that the calculus about harm changes when dealing with issues happening outside the United States?

A. In a sense it’s similar to the news media. When I worked at Facebook, our sense of priorities was shaped by the media environment we were in. And that environment in turn reflected the nationality and the interests of the people around us. If you’re running a global platform, it’s important that you try to overcome that bias. If you’ve been reading news media from Southeast Asia, you would have a very different view of the importance of events in Myanmar.

Q. So it’s kind of a diversity problem.

A. It’s a cognitive diversity problem, yes. You need native language speakers. Then, if that person is relatively junior in the organisation, how does it get escalated? That’s a structural question which companies need to look at. But the starting point is having people who are reading the news from particular countries. Otherwise, you won’t have any chance of understanding things before they get out of control.

Q. So far decisions about falsity have been made by third-party fact-checkers and decisions about harm, by Facebook content moderators. Do you think it’s right that decisions about harm and falsity are made by different people?

A. Fact-checking is a very difficult area. The reason I say that if something is merely false but not harmful, it’s very unlikely to be removed. Fact-checkers are trying to clean up the public space from falsity. I’ve been a politician for many years and politicians often stretch the truth, exaggerate, frame opinions as facts. In the UK, for example, in every election, the Labour Party will say the Conservatives are going to privatise the NHS, based on some crumb of fact somewhere.

These claims are part of the political debate and arguably they don’t cause harm in the classic sense of direct harm. However, a fact-checker is going to want to manage that content. So you do end up sometimes with a situation where the platform standards are saying, “Yes, it’s false but it’s not really meeting a harm test,” and the fact checker is saying, “Yes, but the falsity should be sufficient.”

Q. Sometimes this is not an easy call. In late March, Cristina Tardáguila, from the International Fact-Checking Network, told us they came across messages saying that drinking pure alcohol cured COVID-19 and laughed about it. Then they discovered that dozens of Iranians had died from doing exactly that. So how do you think the calculus on harm has particularly changed for platforms during the pandemic?

A. I think the calculus on harm was already shifting in the context of the anti-vaccination movement. A lot of thinking was sort of done around that and then COVID-19 just accelerated it. There was evidence that the numbers of cases of measles had increased, and people had died. So Facebook had adopted a policy stating that this was pretty robust evidence of harm. On the example you give on the Iranians and COVID-19, I think we are in a place where if you can show that Iranians are dying because of that information, that creates a very compelling case to act.

Q. Then why do you think Jair Bolsonaro’s video praising hydroxychloroquine and encouraging the end of social distancing was taken down and Donald Trump’s comments saying similar things and encouraging people to drink bleach were not?

A. The greater the politics, the more reluctance there is. And I understand why some people may feel quite the reverse. But I think removing content by Donald Trump will always have to meet a very high bar. It’s just so political and partisan...

Q. Both leaders were saying basically the same things.

A. They were. But this is where trying to apply a universal principle becomes difficult. You’re going to take more of a risk in a country that’s further away. So if it’s a president of a small, far off country, the decision is more likely to come down in favour of removing their content.

Q. Brazil is a really big country…

A. It’s a big country but it’s not as close to the company as the US. Some of it is cognitive bias, but some of it is real in the sense that the political implications of removing content by the President of the United States in particular are going to be very significant.

I think it’s safe to say it’s very hard to construct these kinds of uniform rules, but I don’t think Trump is exempt. I think there are limits, so that’s why I described the framework as a weighing scale that you’re trying to weigh up all the time. Trump could say something that is so harmful and so false that even he would be at risk. He doesn’t get a free pass. But the fact that he occupies the position he does weighs very heavily on the other side of the balance.

The other factor that I’ve highlighted is resilience. The very fact that he says things in the context of the United States is relevant because everyone is going to pile in and say that’s nonsense. And that weighs against intervening. It is much more dangerous for somebody to say something in an environment when nobody questions it and there’s no debate around it. In the US there is so much robust debate that arguably the population in the US is much more resilient to nonsense from their politicians.

Q. Do you really think there’s anything that Trump can actually say that would make the platforms take it down?

A. Yes. If the president of the United States were stupid enough to say voting day is on Monday when it’s on Tuesday, that would be taken down.

Q. What about a false claim on vaccinations?

A. Vaccinations are an interesting case. If the President were to stand up and say, “Don’t get your measles vaccines, they cause autism,” I would expect the platforms to actually intervene because the science is so strong and the harm he would cause is so clear. Some people would mention climate change in response to that. But once you start moving away from direct harm, I don’t think platforms would act.

Q. Everyday newspapers publish contradictory pre-prints on different aspects of the disease. One of those pre-prints has been weaponized by right-wing people who claim COVID-19 is much less deadly than people say. How do you think platforms will deal with something like that? It’s probably harmful but also partisan and not easy to prove as false.

A. That kind of a selective use of information is much more comparable with the climate change debate. People who support the view that the virus is less deadly will selectively choose information that helps support their case in the same way that people who don’t like the idea of governments acting on climate change will selectively produce information about that topic. I struggle to see the platforms intervening on that.

When people express those views, they are expressing a point of view which I describe as seditious. If that’s their position, then you have to question whether suppressing speech or trying to correct it makes any sense at all.

They’re making a point. So the symptom of their unhappiness is that they selectively pick information and put it out there. But the information is not the cause. They haven’t read the paper and then have been persuaded that COVID-19 is less infectious. They have decided that they disliked the lockdown and therefore sort out something which supports their view. And so the classic notion that it’s a rational discussion where we’ll just present you with the facts and then we’ll fix the problem is sort of missing the point.

Q. Facebook doesn’t take misinformation down entirely. It downgrades it and those decisions affect its distribution. In some places, right-wing activists and politicians are accusing Facebook of censorship for doing that. Is there any way that Facebook can actually avoid that perception?

A. The core notion of fact-checking is that people are being misled because the wrong version of the truth is out there and that we can substitute the untruth with the truth and therefore fix the problem. That core notion is challenged when we get into the political space and the reason why the platforms went for that third-party fact-checking model in the first place was to avoid getting pulled into partisan battles.

It turns out this is quite a weak defence. We need an urgent discussion about the extent to which platforms should or shouldn’t have a partisan view. Newspapers in countries like the UK and Spain have a political viewpoint. We all understand that. And if we read a newspaper from the other side, we would probably think it’s full of misinformation.

On social media we’ve kind of got all of that mashed up together. Am I going on to a social media platform as a Guardian reader saying, “How dare you, social media platform, allow all these Daily Mail views”? That’s what it feels like sometimes. So sometimes we’re expecting the platforms, almost asking them, to narrow the world or to align with our political view.

That comes from both sides and fact-checkers unfortunately are not enough. The problem some people have is about the editorial line of other people on the platform and that’s not resolved by fact-checkers.

Q. Is it possible to get politicians to regulate these issues? Look at what happened in the last UK election.

A. I didn’t see anything unusual in the last election. It stayed within the bounds of what is culturally acceptable in the UK. If you lose an election, you will always make a lot of noise. But there’s not much there that you would want to make illegal in a free, open democracy. When we think about regulation, we should look at it in the context of overall societal attitudes to sedition, to the notion that you can be seditious and attack the state. And I think that’s actually what’s framing it.

So a country like the United States, where sedition is not just tolerated but celebrated as part of the founding myth of the country, is going to be super-permissive. Countries like Singapore will act very differently. That I think is the lens I’m trying to develop which is a better way of trying to understand how governments are approaching this.

Q. Do you think the calculus of the platforms on COVID-19 will change as politicians raise their voices against lockdowns and other government measures?

A. Yes. I’ll use the anti-vaxxers example again. Some prominent politicians in Italy are sympathetic to the cause. That changes things because once you intervene as a platform, then your intervention is partisan. It has a disproportionate effect on one side of the political debate.

Some people will say: “That shouldn’t matter. You should just ignore politics.” But you can’t ignore politics entirely. And not because you’re worried about the backlash but because platforms are trying to serve everyone. They want to be the Daily Mail and The Guardian. If a policy makes you feel like just the Daily Mail or just The Guardian, that changes the relationship you have with the people who use your service in that country. And that’s a real issue. You don’t get to choose whether a politician takes a cause up. So they set the terms of debate.

As the COVID-19 debate rumbles on, some of the measures platforms took early on are going to be harder to take.

Q. Just to take things to the extreme, I guess the argument here is basically that Facebook would have taken action towards Hitler let’s say in 1928, but not in 1933?

A. I don’t think it’s a question of not taking action. I think it’s a question that the equation changes. The Hitler scenario is really difficult because of the popular mandate that he had. That just makes it extremely hard. However, the political character would change but the harm calculation may also have changed. None of these features are static.

So somebody could become more politically important. But if there is increasing evidence of harm, then you may need to act. It’s a difficult one. But the threshold at which a platform would act against a winning party in an election is really high. Some people may interpret that as saying, “Well, you just don’t want to act because they won and you’re scared of them.” But it’s actually from a fundamental democratic point of view. Who the hell are you, platform, to contradict our choice as voters?

That’s really hard. As I say, I think there are limits. But I think the equation is very difficult when you get into larger factions. It’s easier to suppress fringe parties than mainstream ones.

Q. I would like to talk briefly about the challenges of the oversight board. What do you think of the design of the board and its composition?

A. If fact-checkers couldn’t answer the problem fully because they’re working only in that space of truth and falsity, the oversight board will look at the broader picture. It brings together a group of people who are politically sensitive, sensitive to different cultures. When we were doing some of the workshops around it, we would look at questions like the treatment of Hezbollah, a designated terrorist organisation that’s also in government in Lebanon. At what point does somebody expressing support for Hezbollah is expressing support for terrorism? Those are the kinds of nuanced questions which are not about truth and lies but about political judgments, and I think this board is going to be able to look at those.

Q. What are the risks?

A. The risks are evident. Even in a room full of smart people, I’m not sure we’d have a single view on how to treat Hezbollah and people who talk about Hezbollah are online. So that’s going to be the challenge. They are going to ultimately have to resolve the question and say this should stay up or come down. But as a group of people, you have to say that the potential is there. They are at least going to bring a fresh set of perspectives to this.

Q. Do you think there’s any chance to make it an oversight board not just for Facebook but also for any other social media company?

A. That was the intention. Facebook decided to push ahead and create this thing because Facebook was under so much criticism from both sides. But if a group of people with broad cultural perspectives and a lot of relevant expertise get good at making decisions about Facebook content, exactly the same skills would apply to other content.