How a women-led bilingual publication reports on the Indian farmers’ protests

Women farmers protest on International Women's Day at Bahadurgar, India. REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui

For close to four months now, farmers from the agrarian states of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh have camped on the borders of Delhi. They are protesting three farm laws hastily passed by the Indian government in September 2020.

Farm unions are demanding a repeal of the laws. They claim they will affect their livelihoods and open up the agricultural sector for corporate exploitation. The central government has proposed to suspend the laws for 18 months, a proposal farmers unions have rejected.

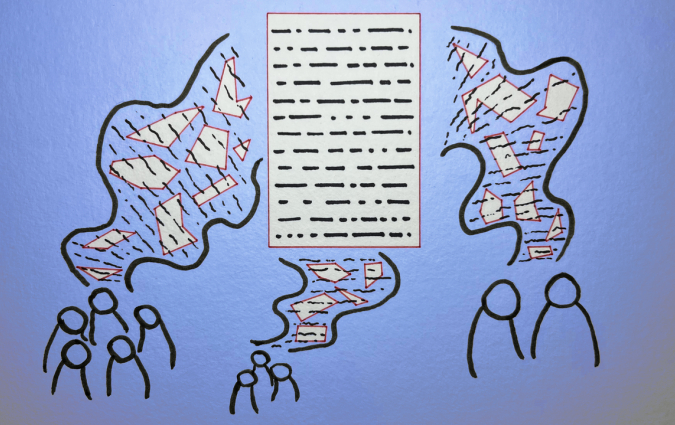

Over the past three months, farmers have erected tents at various points of entry into Delhi, where they’ve spent the worst months of winter. The government has built concrete barriers and razor wires to keep the tractors from entering the nation’s capital. When the protests gathered steam, activists, farmers and students began publishing small leaflets called Trolley Times, which were circulated among the demonstrators in the five protest sites and whose content was later put on a website.

In February 2021, Karti Dharti, a women-led publication, began printing news and opinions on the protests. It is published every fortnight and it is meant to target not just the protesters but also the general public with a specific focus on women farmers and Dalit farm labour. Dalits are oppressed castes and form the bulk of those working in the farms for landowners. Only a minority of them own land.

Anyone can download PDF copies of the English version of Karti Dharti from its website. But the co-founders also print hundreds of copies and distribute them in protest sites, and in major cities and towns across Punjab.

Karti Dharti is published in two languages (Punjabi and English) and three scripts (Gurkukhi, Shahmukhi and Roman). It has just run a special edition for 8 March. Sangeet Toor, one of Karti Dharti's founders, spoke to me about her professional journey, and explained why these protests have the potential to change India and how she plans to document such changes.

Q. What does the name Karti Dharti mean?

A. Let’s say it’s the feminine version of Karta Dharta, an expression that used to refer to men who shoulder responsibility for the family.

Nausheen Ali, a friend of mine who teaches in New York University, started a project called Karti Dharti. Her project focuses on ecological farming and investing in farm produce which is more relevant to a particular geographical area.

We decided to adopt the same name since we will also broadly look at similar issues beyond just the three farm laws. We have been in a deep agrarian crisis for the past 150 years. We need to talk about it, especially now that the mirage of the Green Revolution is broken [In the 1970s and 80s, Indian agriculture was converted into an industrial system with the adoption of modern methods and technology, such as the use of high yielding variety (HYV) seeds, tractors, irrigation facilities, pesticides, and fertilisers. While this increased crop yields, it is criticised for increasing regional wealth disparities within India and causing immense ecological damage.] Groundwater levels have gone down and we are living in polluted areas. These are all the issues we will deal with in our publication.

Karti is also any woman who does work with her hands. Dharti is the earth, land itself.

Q. How has your journey shaped Karti Dharti?

A. I lived in the US for many years. I am a domestic violence survivor and was a housewife until a few years ago. I chose to do a masters in cyber security at George Washington University because I felt tech education would empower me. I did it also to overcome my own challenges because when you go through violence at home, it takes so much away from you.

When I was in the US, Donald Trump was in power. I felt I didn't want to be in a toxic environment because I was already in a toxic domestic environment. So I came to India, without realising that Narendra Modi was equally toxic. I had participated in the women’s march in Washington DC and marched against Trump’s immigration policies. But I was alien to whatever was happening in India and didn’t want to learn anything because I was thinking of going back to the US.

Then the farmers movement started. I went to my first rally in September 2020 in Raikot, near Ludhiana. When I heard the farm leaders speak, I was mesmerised. I really wanted to learn more about this. This was bigger than the women’s march. These are my people. For the first time I felt like I belonged in this place.

During the weekdays, I went to work. On weekends, I went to the protests. I drove from Chandigarh to Sangrur, Ludhiana and wherever. I listened to the leaders and that gave me an opportunity to write. Now I feel I might not go back to the US at all. The farmers’ protests kindled that part of me which stands up to someone who is violent or tyrannical. I always believed that the personal is the political. Now I think the political is the personal too. This is what Karti Dharti focuses on.

Q. Who runs Karti Dharti along with you?

A. The first edition of Karti Dharti was out on 15 February. Just before that, I was severely trolled online and some of the women who had volunteered to start the Hindi content decided to not continue with us. When they pulled out, I told my sister about it and she helped. Navjeet Kaur, who is a friend and a designer, takes care of the design of the website and the newsletter.

We got tremendous help from our friends in western parts of Punjab. One woman offered to translate our pieces on the same day into the Shahmukhi script. We have a few friends in Delhi who are helping us with the website. Each one of us is doing three-four people’s worth of work. We are not funded by anyone.

Q. Do tell us more about the type of content you publish.

A. I write mostly about the women I meet in the protests. These are women I learn from and I am inspired by – some of them are farm leaders. Some are women who have joined the movement for the first time. Some are from the labour movements. But at Karti Dharti we also invite the women themselves to write about their journeys. Many of them could be housewives talking about how the protests turned them into political animals, about their fight with patriarchy in farming communities or about their ideas of peasantry in Punjabi culture. In our first edition, we wrote about the Dalit labour activist who the police had arrested and allegedly sexually assaulted in prison.

Q. Why did you feel the need to start Karti Dharti?

A. I work full-time as a cyber security analyst and this is my first time doing independent journalism. I have been writing for The Caravan and The Wire, and although I appreciate the platform I got on various digital outlets, there were so many stories that went unheard.

I realised that I would not be able to tell all those stories unless I published them myself. When I began going to the protests, I got in touch with a lot of people in the villages, including women farmers, Dalit labourers, women whose husbands died by suicide because they could not repay farm debts and others.

When the protesters entered New Delhi and there was some violence, independent journalists were attacked. That’s when I decided we needed a platform of our own. That’s how we decided to start Karti Dharti to do three things.

First, to give space to those who are not heard. Second, to throw a challenge to the state of society today. Third, to capture the political awareness that was happening on the ground. We wanted to capture the evolution of not just rural women, but also of women from urban areas.

Q. How do you see the protests right now?

A. Since October, I am seeing a subtext to these protests. The subtext is the bigger political awareness that people are gaining. This is the kind of learning that cannot be unlearnt, especially among women.

The lesson is that the real power is in their hands if they are organised and disciplined. That the leaders who are ruling India are not that powerful. That if people get together, they can bring about change in laws and policies. That is the subtext to the repeal of the farm laws.

When the farm laws are repealed, the focus of these protests will go away but we will be left with this subtext. That’s where we want to go with Karti Dharti too. We want to keep those narratives going and not let them die out.

We want to talk about the bigger changes our society needs. People are politically aware now. They want to know more. They are disciplined. This is the time to keep on with the initiative.

Q. How important is it for the movement to get international attention?

A. It is very important to be recognised worldwide. I like the timing for when international celebrities jumped in, it came on Feb 1 when twitter accounts of so many people were suspended. On February 3, Rihanna tweeted and then Greta Thunberg. You can silence the local voices, because you think Twitter is a platform that can be controlled by the national government. But you realise people beyond the Indian boundaries are keeping an eye.

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist, with a specific focus on human rights. Since 2011, she has reported from 12 countries across the world for outlets such as 'The New York Times', BBC, the 'Guardian', 'TIME', 'South China Morning Post' and 'The Hindu'. Samples of her work can be found here.