Journalists should recognise how their reporting impacts news events, an anthropologist argues in a new book

Francis Cody, Director of the Center for South Asian Studies at the University of Toronto.

Francis Cody is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology and the Director of the Center for South Asian Studies at the University of Toronto. His research focuses on politics and media in southern India, specifically the state of Tamil Nadu. His book The News Event: Popular Sovereignty in the Age of Deep Mediatization (2023) explores the fields of law, technology and political violence in the context of journalism and populism today, and explains how journalists play an active role in shaping news events they report on.

I spoke to Cody about the book and about the ways technology is reshaping journalism in India and beyond.

Q. How do you define a news event?

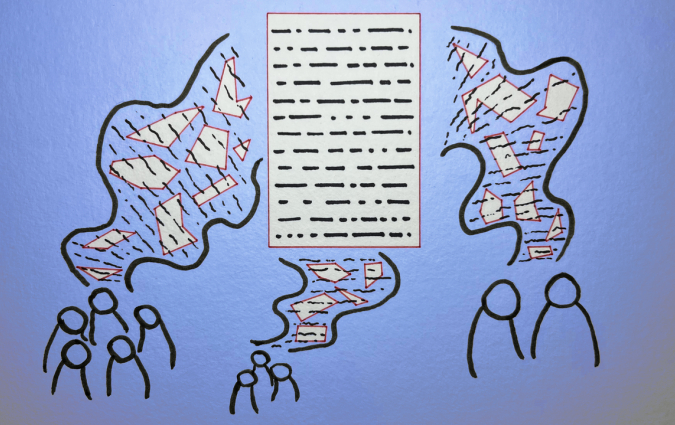

A. The concept of “the news event” refers to that moment when it becomes difficult to distinguish between the event being reported on and the news reporting itself. There is a sort of collapse that occurs between the storyline and the act of telling the story.

This might appear to be a rather abstract concept. But I think it helps to think through concrete examples of this phenomenon.

Q. Can you go through one of these examples?

A. The book begins with the arrest of M. Karunanidhi, patriarch of the Dravidian movement for Tamil autonomy and one of the most important political leaders in India at the time.

Mr. Karunanidhi was arrested in 2001 at the age of 78 past midnight in his home in Chennai for alleged corruption when he was Chief Minister of the state of Tamil Nadu. But this scene was caught on film by a TV news station connected to his own family, and the footage of the arrest came to define how people experienced its political significance.

By the morning following the arrest, this footage was broadcast around India and it had become the main frame through which people interpreted the meaning of this act. News coverage of the arrest centred as much on the fact that it had been filmed, leading to widespread protests and to the eventual intervention of the central government.

This shows how a news event is often shaped by how it is reported in the media. Today we have become more attuned to how important news coverage is to our experience of politics.

Q. Why have you chosen to look at the Tamil media in India? What is unique about it?

A. The news media in Tamil Nadu, both Tamil and English language, is a fascinating space to explore these ideas for a number of reasons.

First of all, many of the most important newspapers and news channels in India have been based in Chennai. For example, The Hindu, The Indian Express and Sun TV News. The Hindu remains India’s paper of record, and Sun TV went on to become one of Asia’s most profitable media companies.

Tamil Nadu is a relatively urban state that has been quite captivated by the news, with a long history of public newspaper reading teashops and deep and early penetration of satellite TV news in cities and even into rural areas, with the highest rates of internet usage and very cheap cell phone data.

Another reason why Tamil Nadu is important for understanding the connection between media and politics is that the leaders of the Dravidian movement, which has defined politics in this state for over half a century, were particularly adept at using mass media to spread their message.

Q. How have they used mass media?

A. The founders of the DMK Dravidian party created films that helped propel the party to power, and superstar actors went on to lead the state as Chief Ministers on a number of occasions. The populist style, centred on the image of a powerful leader connecting “directly” with the masses, has been a defining feature of parliamentary politics in Tamil Nadu. The DML leaders have been especially sensitive about their public image, so negative news has often led to criminal defamation charges or even sedition charges against journalists, something I write about in my book.

The news media has also been very important in shaping political participation in the state. The DMK spread through a large number of partisan newspapers launched by its leaders across the state. This party was also among the first to launch its own affiliated TV news channels, the first being Sun TV News, which filmed the arrest I described before.

The DMK’s main rival party also launched its own TV channel in 1999. Today eery party in the state has launched TV news channels of their own. Many of these channels lose quite a bit of money. But profit is not necessarily the point because they are seen as propaganda channels.

Q. In the history of modern TV journalism, was news ever independent from the world on which it reports on? In other words, was the element of performance always a part of it? What is different now?

A. TV journalism was neve completely exterior to the world on which it reported to the degree that its reporting always had performative effects in the world.

For example, televised images of military violence against civilians in Vietnam could be said to have had a large influence on how the war was perceived in the United States. And political events have long been staged in anticipation of television news coverage, even if they exist independently.

What is different now is the extent to which it has become difficult to think of what a political event would mean without real time news coverage. The midnight arrest of Karunanidhi is one example of this. But we can also see the same issue in more recent events.

Q. Could you give me an example?

A. In the book, I compare how coverage of a famous outlaw in the 1990s and 2000s worked through video cassettes that were later broadcast on news channels with a more recent series of events where a vigilante accused of murdering a young Dalit student was conducting TV interviews through Skype while on the run from the police.

The mere fact that TV journalists could interview someone accused of a heinous hate crime through these technologies was an event in itself, and it was one that led to a great deal of debate about ethics.

What I find important in this context is the fact that televised news’ success in shaping the very events it reports on has become a problem, as a large part of journalists’ legitimacy rests on the claim that they are only messengers of information.

As “outsiders” to the world they report on, journalists are supposed to be the only people responsible for the act of transmission or publication of something that originated elsewhere. But if journalists are in fact responsible for producing events of political import in self-conscious ways that invite further news coverage of their actions, we can see how the emergence of feedback loops can throw into question their status as outsiders.

This became clear to me, for example, when I realised that some journalists actively court defamation cases from political leaders, not only to expose and amplify state wrong-doing, but also in an effort to project their own fame. It’s often said that journalists should not become the news. But this ideal is under a lot of stress now. Networked media and the capacity of citizen journalists to produce news events has exacerbated this problem.

Q. Does social media dilute the nature of the news event?

A. The answer to this question depends on what kind of news event one is looking at. A news event might well be amplified through recirculation across diverse media channels, including a now mind-boggling range of YouTube news channels in India and elsewhere.

The same event, sometimes captured by a cellphone, will be minutely discussed and analysed to death by news outlets on shoestring budgets in ways that can often obscure serious investigative reporting about what actually occurred in the offline world.

At the same time, the diversity of news outlets in the age of social media leads to the well-known dynamic of siloing the circulation of information that should be of interest to all citizens. In India, news events that should be of importance are often ignored by mainstream media who are subject to government scrutiny.

I’m thinking of caste atrocities that show the police or a political party’s reliance on dominant castes in a bad light, for example. These same events can live subaltern lives of circulation on social media platforms that are now much less capital intensive, but the impact of such reporting might well be muted or diluted.

Q. A journalist used to expect some kind of impact from her reporting. In today's media environment, there is a flow of news events and journalists do not expect impact to occur. As an anthropologist, which kind of effect would you say this has for society?

A. This is a concern I have encountered among many journalists I’ve met. Newspaper headlines used to punctuate the flow of time. Publishing an exposé of a government scandal would lead to phone calls from the Prime Minister, demanding the problem to be fixed. This kind of performativity is perhaps harder to achieve in a world of 24/7 news channels, geared as it is toward visual spectacle and circulated as it is now through short clips on cell phones on WhatsApp.

Our governments feel less compelled to respond to criticism and more likely to fight bad publicity through their own PR channels, and it has become especially difficult for journalists to pursue complex stories

At the same time, important news stories have not gone away. What has occurred in recent years is a fairly substantial redistribution of the capacity to record critical events through cell phone cameras, thereby bringing non-professionals into the sphere of news production.

Q. How?

A. Some events that could simply not have been captured by professional camera operators have made a huge impact on public perceptions of the police. A good example is the murder of George Floyd, which was filmed by a witness on their cell phone and had a massive influence on the intersection between politics and race.

Of course, this event was further covered both by professional journalists and many others. But it definitely marked a moment that many now see as a rupture with existing political arrangements, even if police brutality continues in the US and elsewhere.

In my research on Tamil media, I show how footage of police violence captured on cell phones has similarly reoriented the political sphere. So, while professional journalists have certainly lost some of their monopoly on the capacity to make an impact through their reporting, the story does not end there.

Q. What should a journalist keep in mind while reporting on a news event, given that she might be influencing the news?

A. Many journalists are very aware of their potential to influence events while reporting on them. The question then becomes: how should one wield this capacity? And the answer really depends on the situation one is in and what one is reporting on.

I have recently been paying closer attention to reporting on cases of caste-based violence, for instance, and in these cases journalists and editors often have ambiguous and conflicting responsibilities as they can further inflame an already dangerous situation.

On the one hand, comes the compelling duty to report a wrong, so that people can know what happened and there is a legal remedy. On the other hand, reporting can easily lead to deepening conflicts, increased attacks on marginalised communities, and a general breakdown of social relations in a given place the journalist does not necessarily belong to.

Journalists often avoid naming the communities involved and it is often up to the editor to know when to draw the line around what information should be shared with the public. But the editors are often even more removed from the situation on the ground and must sometimes rely on their intuitions and experiences, or on a calculation of the political or economic blow-ack their organisation might face. This has made many news organisations very reluctant to report on a number of events of caste-based violence.

At the same time, journalists show nowhere near enough restraint in cases of gender-based violence, knowing full well that the victims can suffer negative consequences as a result of their reporting.

State censorship is not the solution to this. Collective self-restraint from journalists appears to me to be the best path forward, yet it often remains up to the individual journalist to do the right thing.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time