How Ugandan reporters managed to cover the latest election despite a climate of fear

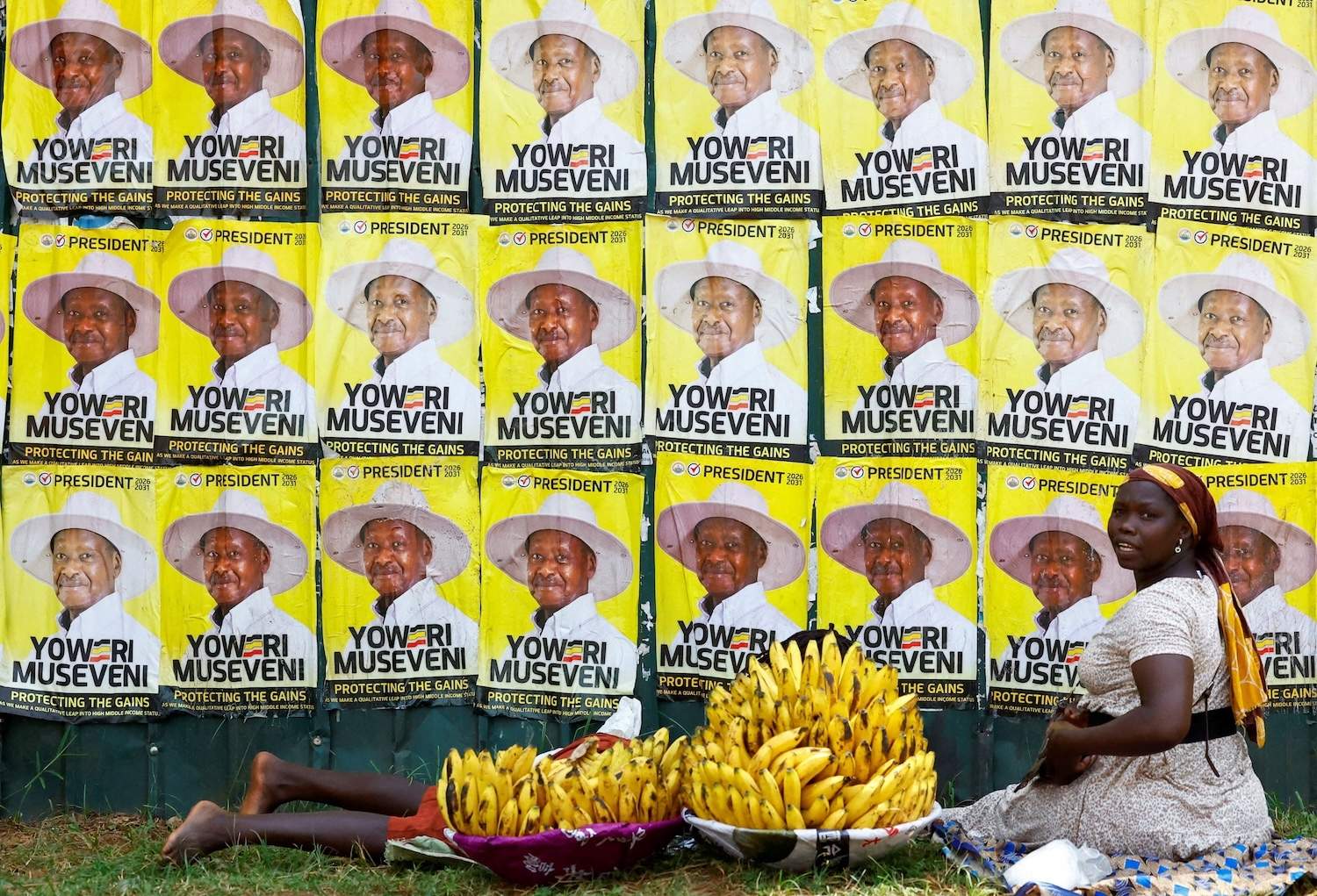

Women sell bananas near campaign posters of Uganda's President and the leader of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party, Yoweri Museveni, following the general elections in Kampala, Uganda, January 17, 2026. REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya

When Ugandans went to the polls on 15 January, the nation’s journalists faced a trial by fire. The country’s President, Yoweri Museveni, who has ruled for nearly four decades, was seeking another term at age 81. He was declared the winner a few days after the vote.

Two days before the election, citing the need to curb “misinformation, disinformation, electoral fraud and related risks,” the government shut down the nation’s internet access. Journalists faced escalating threats from security forces, while newsrooms operated under strict censorship guidelines that dictated what could and could not be reported.

Ruth Adong, content lead for the Good Morning Africa podcast and head of the business desk at Sanyu FM, a popular urban radio station that has broadcast for over 30 years, recalled a time when journalists could find shelter behind police lines if a situation turned volatile.

“There was an understanding that we were there to put out a story,” she said. By this year, that understanding had evaporated. Now the police were often the ones seizing equipment or beating reporters, and the directive from editors was starkly different: “If things get dicey, get out of there.”

For Adong and hundreds of reporters across the country, the internet blackout was a weapon that crippled verification and cut journalists off from editors, sources, and publishing systems.

In previous elections, blackouts lasted a day or two. This time, the silence stretched for nearly a week.

“In 2016, you could still use VPNs,” Adong said. “By 2021, there was no access at all. In 2026, the shutdown was total.”

A risky scramble to ‘beat the system’

Godfrey Badebye, a freelance journalist who leads Ugandan investigative hub Ukweli Africa, said the blackout forced reporters to abandon digital workflows altogether.

“It was like working in the early days of journalism,” he said. The process became a daily, risky scramble to “beat the system.” Reporters acted on whispered tips about where a signal might linger.

“It was, ‘Go and park around here, there’s Wi-Fi,’” Badebye recalled. Even when reporters briefly got online, basic tasks became ordeals. Uploading a 100 MB file could take an hour.

He recounted one incident in which he shared a Google Drive file with an editor but didn’t grant them editing access. “We had to drive two hours away just to click a yes for that file to be accessed,” he said. “It was crazy.”

For television reporters like Kamana Ivan Walunyolo of NTV, the blackout meant losing the visual language of their medium. He and his cameraman became radio reporters by necessity, describing scenes over phone lines to studios in Kampala.

Stationed in Entebbe, about 47 kilometres from the capital, Walunyolo had to race against the clock. “I had to jump on a boda-boda [motorcycle taxi] to deliver footage.” His colleague in a more remote area had to send footage by bus. “It took a full day to arrive in Kampala,” Walunyolo said, losing the important news cycle in the process.

A human network to beat blackouts

To counter the shutdown, some of Uganda’s largest media groups fell back on organisational heft. Ntege Hamza, a senior manager at Next Media, said his group deployed over 100 correspondents across the country, relying on a decentralised network to gather information.

“We maintain representatives in over 114 districts,” Hamza explained, a structure designed to capture local developments without heavy reliance on those severed digital connections. This allowed outlets like NBS TV to keep reporting on what was happening

The blackout did not prevent journalists from going to the field, but it crippled digital reporting workflows. Caroline Marcah, a television and digital journalist, said election coverage became “strictly on television” because most online reporters could not publish or access information once the internet was shut down.

Hamza recalled seeing crowds gathered around radios and televisions in shops and buses, a scene from a bygone media era. “It was quite interesting,” he said. “It reminded you why this work still matters.”

According to Muthoki Mumo, Africa Programme Coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), the shutdown made abuses harder to document and to expose in real time, “reducing global and public scrutiny.” It effectively silenced coverage, compounding the effects of the communications shutdown.

“The blackout did not merely disrupt reporting,” Mumo said, “it entrenched impunity, narrowed space for independent journalism, and increased the likelihood that election-related abuses occurred unseen and unchallenged.”

But the internet shutdown was only one part of the pressure journalists faced. As election day approached, the risks extended to physical violence, surveillance, and direct intimidation by security forces. What made this election particularly dangerous, Mumo said, was this combination of tactics deployed against the press.

“Elections in Uganda are historically dangerous periods for journalists,” she said.

In the months before the 2026 vote, CPJ tracked a pattern of assaults, arrests and harassment targeting journalists and documented censorship, Mumo said.

CPJ’s findings suggest the pressure on journalists was structural, shaping newsroom decisions and narrowing the scope of election coverage well before votes were cast.

A multi-front assault

The 2026 elections were the culmination of a years-long erosion of press freedom in Uganda. According to the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, Uganda ranked 143rd out of 180 countries, a 15-place drop from 2024. This decline occurred amid direct threats from the highest levels, including a 2022 warning from the influential military chief and son of the president, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, that critical journalists would be crushed when he came to power.

The threats materialised into systematic violence. Just months before the presidential election, Ugandan armed forces attacked at least 18 clearly identified journalists covering by-elections in Kampala. Security forces beat reporters and subjected them to degrading treatment. These coordinated attacks demonstrated that the risks journalists faced were not isolated but part of a structured pattern of intimidation by the state's own security apparatus.

UN experts also issued an urgent appeal warning of a "declining trend" in human rights and the “suppression of dissenting voices” ahead of Uganda’s elections, citing journalists being attacked, having equipment damaged, and losing media accreditations. They called on authorities to guarantee internet access and ensure a safe operating environment for the press. Regional human rights bodies echoed the same concerns.

In the months before the election, journalists faced systematic intimidation that shaped coverage long before the polls opened.

Badebye described a long wait for state accreditation, with many journalists dropped from the list after extensive vetting. “I personally wasn’t accredited,” he said, “yet I still managed to do the work.” This bureaucratic filtering became the first layer of control.

The restrictions extended to foreign reporters as well. During the same period, Ugandan authorities expelled three French journalists who had arrived to cover the election, even though they had documentation to work in the country. The government described the expulsions as “administrative,” saying journalists must comply with national laws and accreditation rules.

A state of direct surveillance

The atmosphere of state intimidation translated into direct surveillance for journalists on the ground.

Walunyolo received a call from a friend with ties to intelligence, asking for his location. After he answered, the instruction was clear: “Stay there.” His friend explained that security forces had staked out a route, anticipating that Walunyolo would head toward a violent scene unfolding nearby. From that point, Walunyolo adjusted his reporting, staying away from scenes where he knew he was expected.

At one polling station near military barracks, Walunyolo and his cameraman were documenting what appeared to be repeated voting when they were confronted by a uniformed officer and a member of the Special Forces. The officer told them they were not wanted at the station. “I am not accountable to you,” he said.

Prioritising safety, Walunyolo and his team left immediately. A few days later, plain-clothed soldiers and uniformed police officers reportedly arrested Walunyolo while he was conducting live coverage at another polling station. He was released after being interrogated. The authorities wanted to know why he was filming security installations and accused him of “siding with the opposition.”

“You’d better say everything is okay”

Ruth Adong faced similar pressure. At a polling station where biometric machines were failing, a local official confronted her. “You’d better say everything is okay,” he said, accusing her of reporting for the opposition. She pushed back. “We cannot say everything is okay,” she told him, “when you can see that things are not going fine.”

Those pressures were not experienced evenly across the profession. For women journalists, election coverage carried additional risks. At gatherings ahead of the election, women reporters raised concerns about sexual harassment in the field and being passed over for deployment.

Adong said newsrooms tended to pick men over women for field assignments. “It starts from the newsroom,” she said. “Even before you get to the field, you’ve already been sidelined because of your gender.”

“People don’t take you seriously,” she said. “You have to almost work twice as hard to be heard and appreciated.” The disparity, Adong noted, was visible in the coverage itself, with far more male reporters than female reporters deployed across the country.

A ban on reporting election results

These physical threats were matched by institutional pressures that compromised editorial independence.

The Uganda Communications Commission, the regulator that licenses and oversees broadcasters and telecommunications providers, issued a directive barring broadcasters and platform users from “declaring, announcing, publishing or projecting election results” from any source other than the Electoral Commission. It also prohibited the dissemination of projected or unofficial results, effectively preventing independent reporting of vote counts.

The directive offered little clarity on how journalists were expected to verify digital content. Non-compliance could lead to “fines, suspension of broadcasts, or prosecution.”

These regulatory restrictions were reinforced by actions targeting the support infrastructure journalists relied on. As Mumo pointed out, “the authorities compounded the risks faced by journalists by banning live coverage and suspending media-support organisations.” Together, these measures left journalists exposed to direct threats and without institutional support when they needed it most.

The result was predictable. Even when journalists managed to document violence or fraud, stories often never aired.

“There were many stories that were dropped,” Badebye said. “There was a shooting where people were allegedly killed in one of the constituencies. The reporters went and covered the story. It has never come out until now.”

In some cases, even basic facts became contested. Marcah described reporting from areas where journalists witnessed gunshot victims and burials, but casualty figures varied sharply across outlets. One station reported five deaths and another eleven, but residents insisted the number was higher.

“You can actually see people being buried,” Marcah said, “but then you know your hands are tied.”

Beyond the killing of specific stories, the constant pressure bred a more pervasive form of self-censorship. Over years of intimidation, Adong stressed, newsrooms have begun adopting government framing.

“We have co-opted the police and the army’s language,” she said. “People protest, and we call those protests riots because the police have called them a riot.”

Perhaps most corrosive was the financial pressure on a poorly paid profession. Several journalists spoke of “envelope journalism,” where underpaid reporters accept payments from political actors. “NRM [Uganda’s ruling party] has spending capital,” Adong said. “If they’re giving you a paycheck that looks like your two-year salary, it kind of makes sense for certain people.”

Marcah added that fear has increasingly shaped “what and who” journalists felt safe covering. Reporting on opposition campaigns, she said, came with the risk of arrest, violence or job loss, while journalists assigned to the ruling party faced fewer threats and sometimes financial inducements. “That’s why you find most journalists really trying not to get into reporting when it comes to elections and campaigns,” she said.

Survival through solidarity

Faced with these constraints, journalists set aside competition and quietly collaborated to keep coverage going. Reporters from rival outlets shared interviews, footage and leads across newsrooms, blurring boundaries that would normally separate competitors.

Adong described an informal system in which journalists exchanged material across radio stations, sometimes meeting in person to pass along interviews.

Collaboration was also a core safety tactic. Walunyolo learned he was a target early on and adapted. “The first thing was not to be alone,” he said, “because when you’re alone as a person, the target becomes very easy.”

He and his colleagues began moving in groups to avoid being singled out for intimidation. This protocol proved critical when Walunyolo was detained; his colleagues were able to witness and report on his arrest, preventing him from simply disappearing into custody.

Journalists also warned each other about dangerous places. “People were saying, ‘Hey, don’t come to this area. There’s tear gas, there’s blockades,” Adong said.

Institutional support wasn’t always there, but it proved crucial where it existed. Walunyolo’s managing editor maintained regular contact, texting him to check on his safety after hearing reports that he was a target. The directive was always the same: “Safety first.”

Investigative initiative Ukweli Africa conducted pre-election hostile environment training for nearly 50 journalists, running them through simulations and first-aid drills. The core principle was the unambiguous rule that “no safety” meant “no story.”

Reflecting on the experience, the journalists who reported through the election pointed to hard-won lessons: preparing for shutdowns, prioritising safety, relying on cross-newsroom solidarity, addressing gender disparities, and investing in mental health and legal protection to avoid becoming instruments of propaganda.

The mental toll

Those strategies did little to shield them from the psychological cost of working under tough conditions. The constant surveillance, physical threats, and editorial censorship created a climate of fear that persisted long after the polls closed.

“Every time I hear a dog bark when I am home, I think [the security forces] have come for me,” Walunyolo said, who is always wary now when a stranger stands nearby.

That mental toll has driven some journalists to step away from election coverage or to leave the profession entirely. “My reporting days are over,” Adong said. “I am moving out into less risky ventures. Elections in Uganda are not worth dying for.”

The cost of all these restrictions extends beyond journalists themselves to citizens’ ability to participate meaningfully in democracy. Even weeks after the election, restrictions persisted. “Right now, we still have restrictions on WhatsApp,” Adong said. “We can’t load photos properly.”

Faced with an increasingly hostile environment, journalists say survival depends on collective action. “We need to have a strong body that raises a single voice when it comes to injustices that happen to the press,” Walunyolo said.

As Marcah put it, the overall state of press freedom in Uganda reflects the paradox of modern authoritarian control, with the appearance of openness under constant constraint.

“I can’t really say that we have any freedom to do anything,” she said. “It’s like we are free in quotes, but everywhere in chains.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time