How to protect democracies from falsehoods? By empowering the young with open-source investigation skills

Flowers and mementos left by local residents at the crash site of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 near the settlement of Rozspyne in the Donetsk region in July 2014. | REUTERS/Maxim Zmeyev

This piece highlights issues posed by weaponised information in the current UK news media environment and presents a pedagogical counter-strategy to counter it. Whilst the issue is not new, the threat of disordered information has been accelerated by smartphone technology – and might be further turbocharged by artificial intelligence.

It is easier than ever before to influence narratives and counter-narratives and offer politically destabilising alternative “truth” logics. These factors require a concerted response to mitigate the effect they may have on democracy. Therefore, news consumers should be encouraged to take a sceptical (but not cynical) approach to information sources and empowered to critique and verify for themselves through the acquisition of open source investigation skills.

This is seen as a way of countering the impact of disordered information. Once inside the news ecosystem of a given context, this disordered information can influence narratives and the scrutiny of those counter-narratives. Furthermore, it can be a domestic and/or foreign policy tool in peacetime and conflict scenarios taking various forms from “news” to conspiracy theories, and rumours which can influence or even radicalise individuals. It can artificially stabilise, or destabilise, governments and has contributed to a rise in populism and a decline of trust in news and other liberal institutions.

However, whilst the problem of weaponised information is broad and multifaceted, ways of tackling it are less clear. Fact-checking and verification initiatives by mainstream media do not often reach social media audiences and fall-foul of a “problem of truth” whereby mainstream news can be seen as “establishment” and therefore partisan.

The goal of previous information warfare campaigns by foreign actors has been, at least in part, to undermine trust in liberal institutions. In such an environment, establishing authentic truth is problematic as is the regulation of online platforms within liberal and transnational contexts. Counter-measures therefore need to navigate the complexity of modern news media ecosystems, and the damage already inflicted on them by weaponised information.

This piece will first outline security concerns and then advocate UK government-backing of teaching of open-source investigation skills in schools, colleges and universities. The article is shaped by the perspectives of its authors, who have looked at this as practitioner and former practitioner turned academic respectively.

How is information weaponised?

The academic literature surrounding weaponised information covers information types, and information strategies, as they have evolved across time and disciplinary space from Cold War Soviet dezinformatsiya to contemporary fake-news and post-truth. So it is necessary to put some order into the empirical and theoretical chaos to identify and assess any jeopardy posed – and formulate a response to it. That’s why we’ve categorised the literature into types, strategies and applications.

Our starting point is this report authored by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan in 2017 for the Council of Europe. Their disinformation, misinformation and malinformation typology exist on a matrix of veracity and intent to harm:

- Misinformation is when false information is shared, but not deliberately

- Dis-information is when false information is deliberately shared and intended to cause harm.

- Mal-information is when true information is shared to cause harm, often by moving information designed to stay private into the public sphere.

We argue that a fourth weaponised information type – bland, non-scrutinising “information” – should be included. Such information may be true and harmless per se but retains the potential for malevolence because it fills space where scrutinising information could be. Including “just” information moves beyond consideration of disordered information types into “propaganda” characterised by intention to influence rather than veracity.

Different strategies apply disordered information in different ways. It can be as a component of true and false rumours, as described by Kate Starbird and Emma Spiro, conspiracy theories as described by H. Innes and M. Innes – and also as apparent bona fide “news” via mainstream channels or online platforms.

What starts as disinformation in this way can then be reported in good faith through mainstream media or shared online by true believers. The variety of potential scenarios means it is necessary to maintain theoretical deftness in terms of where weaponised information is used, how it can be used and through what medium.

It is both a domestic and foreign policy tool – and can be seen in conventional kinetic conflict and non-conventional greyzone or hybrid activity. It can also be spread through all kinds of mainstream and social media – and usually both depending on the circumstances. This piece asks how the adverse influence on news-consumers of disordered information in all forms can be mitigated and how the security jeopardy can be offset.

How does disordered information spread?

Operations seeking to influence narratives and counter-narratives do so by injecting disordered information into the discourse of a given context. Favourable narratives are spread through mainstream and social news outlets. This can be done as “news” and also as opinions and statements. Rumours and conspiracy theory material can also be introduced into the information eco-system via social and mainstream media. This exploits the generosity of the liberal democratic model with its underlying values of plurality and freedom of speech.

Genuinely liberal news outlets are reluctant not to report newsworthy individuals or incidents or to regulate and censor free speech. Similarly, the regulation of social media platforms raises similar issues. By exploiting the innate liberality disordered information can be spread relatively easily (disinformation) and shared inadvertently by outlets or individuals who believe it to be true to a greater or lesser extent (misinformation).

Another aspect of the jeopardy posed is that bad actors can also target the counter-narrative. For example, by repressing or deterring the challenge or scrutiny of a favoured narrative. Those targeted in this way are usually journalists, politicians, lawyers, academics, civil society and anyone who may be influential. Their reputation may be impugned with truthful scandal or false rumour, and shared further afield. Disordered information of all kinds can undermine what these voices are saying and their reputation, dissipating the credibility of their work and maintaining the dominant narrative’s position.

This strategic combination of presenting information as news – and targeting the counter-narrative with it – enables state-actors and others to influence an information space and the political outcomes in a variety of settings, from election results to military campaigns. Only the most illiberal states operate openly. Most operate through proxies or by using the freedom of expression of the countries they are targeting. This is achieved by exploiting existing schisms such as misogyny and racism or through strategic litigation by bringing spurious civil and criminal prosecutions.

The problem of intent: bad actors

It is presumed that those responsible for weaponising information are state-actors or their proxies. Whilst all states do this to some extent, some do it more than others. Those under consideration here are significantly maintaining either domestic power or foreign influence through control of information and tend to be at the illiberal end of the spectrum. However, they also operate behind a veneer of liberality either because they want to maintain a reputation on the world stage or because they are operating what are in effect “active measures” within liberal states and therefore need to maintain the veneer of liberality to be credible.

This is achieved by spreading disordered information through proxy actors in four categories:

- Overt proxies: typically controlled by the state-actor or have a clear financial or ideological incentive. It includes state-controlled public diplomacy outlets such as Russia Today (RT), obvious client journalists, celebrities and politicians, or PR companies working for state-actors. SCL and Cambridge Analytica would fall into this group.

- Covert proxies: operate one step removed from the state-actor but have serendipitously aligned interests and work in tandem to some extent. They include businesses who may benefit from wider business dealings – or ideologically-inclined individuals who gain support from repeating favoured narratives.

- Self-interested actors: similar to covert proxies – but are less ideologically-aligned. Instead, they are performing the role because they perceive some gain from doing so, usually in terms of money or status.

- True believers: people who have consumed the disordered information online or in the mainstream news media (as rumours, conspiracy theories or just information or news) and have been influenced or possibly radicalised by it.

The overt, covert and self-interested actors - be they lobby groups, client journalists, controlled news outlets – are knowingly disseminating disinformation (also possibly malinformation). However, the intent of true believers is different and therefore the same information is misinformation in their case. Social media has expedited this behaviour because it has democratised access to publishing. It is no longer necessary to bypass editors and journalists as gatekeepers – anyone with a smartphone and an internet connection can publish.

This raises the problem of intent. It is impossible to establish in most cases and therefore only overt proxies can be categorised with certainty. There are overlaps between covert proxies and self-interested actors – and between self-interested actors and true believers. What distinguishes them is the closeness of their relationship with the state-actor, and how ideologically aligned they are although this may change over time.

A similar conundrum exists in separating self-interested actors from true believers. It is not possible to establish true motivation in all cases and it is also possible the individuals concerned don’t know or change their minds to an alternative “strategic epistemology” of what they believe to be true. However, whilst proxies exist on a spectrum of intent which is hard to establish, their role as vectors for disordered information remains crucial to the weaponisation of information. The liberal veneer the proxies provide is cover for bad actors to hide in plain sight.

The problem of truth: self-interested actors and true believers

The problem of truth stems from the questioning of certainty as both a philosophical concept and an empirical reality in terms of trust in “news” which can result from information warfare. The veneer of liberality which masks the spreading and targeting of disordered information further contributes to the destabilising of truth – and some of it is deliberately intended to do so. For some news consumers this leaves a vacuum in the information environment which can be filled by disordered information offering alternative truths and realities. At the extreme end of this spectrum is radicalisation.

In this situation there are actors creating an uncertain environment, those filling the vacuum and those affected by it. The latter are the true believers who are inclined to believe the alternative realities presented to them – or possibly are more susceptible due to life experiences and are reluctant to maintain faith in authority. This erosion of confidence can occur in response to a wide spectrum of scenarios, from political crises and economic downturns to personal misfortunes, each providing a catalyst for individuals to question official explanations and frameworks.

Where once an individual might have accepted conventional media reporting or government policy statements at face value, they now perceive inconsistencies or overt failures that prompt deeper scepticism. In the absence of reliable information, online spaces become attractive arenas in which these disillusioned individuals can seek out alternative accounts.

This is how they encounter disinformation deliberately introduced to exacerbate these schisms and communities of like-minded people who articulate a shared sense of betrayal, often weaving together niche theories that frame existing authorities as either incompetent or deliberately deceptive.

Within these communities, the underlying distrust that drew them in becomes both the lens through which information is refracted and the glue that binds members together. The exchanges they witness – content that claims to “expose hidden truths,” personal testimonies reinforcing a worldview of well-orchestrated deception – provide ongoing confirmation that their suspicions are warranted.

The algorithms of social media platforms and search engines, designed to maximize engagement rather than accuracy, exacerbate the situation. As individuals seek more content that aligns with their doubts, they are guided towards extreme variations of the narratives they explore. This iterative process, a kind of ideological feedback loop, can accelerate radicalisation. Over time, the initial kernel of distrust matures into a firm identification with a movement or belief system. The so-called true believers see themselves as truth-seekers who, through relentless scrutiny and the support of their online peers, have penetrated the façade of official narratives.

In their view, they are not victims of manipulation, but rather the enlightened few who have transcended mainstream “misinformation” to embrace the truth—no matter how unsubstantiated or damaging that “truth” may ultimately be.

Truth-seekers therefore are proxies who believe the disinformation and will disseminate it further and act upon it.

Such influence can be seen in electoral systems such as the Brexit referendum, the US 2016 presidential election, Brazil, Kenya and elsewhere. It has also been seen in conflict situations such as Ukraine, Syria and more recently in Gaza.

In the UK context disordered information has been influential in both the Hindu-Muslim unrest in Leicester in September 2022 and nationwide protests following the killings of three children in Southport in July 2024. False information (disinformation) was injected into the news ecosystem and shared as true (misinformation). Bad actors used existing tensions around race, religion and opposition to migration. The origin of the disinformation in both cases is fuzzy, but the vectors are apparent news outlets and social media users (covert proxies and self-interested actors) and “true believers”.

The ‘Bellingcat onion’

We can’t stop the bad actors at source and therefore need to develop counter-strategies. The effectiveness of mainstream media fact-checking on its audience is inconclusive, but crucially it does not affect those who consume news online. Likewise, the regulation of free speech in liberal societies such as the UK’s Online Safety Act is fraught. Instead, this piece suggests giving news-consumers the open–source investigation (OSI) skills to make up their own minds. In a UK context, we advocate the introduction of OSI teaching in schools, colleges and universities.

OSI is characterised by information which is openly available – from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to social media content to geolocation, chronolocation, flight locators and databases from the dark web. It is also known as open-source intelligence (OSINT).

Since its inception in 2014, Bellingcat has used OSI to verify and investigate stories from the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014 (one of the first Bellingcat cases) to the Novichok poisonings of Sergei and Julia Skripal in Salisbury in 2018, and Alexei Navalny in 2020. It has also carried out many smaller-scale investigations into human rights and other abuses in conflict zones such as Syria, Ukraine and Gaza.

Bellingcat’s public-interest ethos has led to journalistic outputs in mainstream and social media, documentaries, podcasts, and submissions of evidence to international courts. The modus operandi is:

- to identify a topic

- to verify it (or not)

- and amplify results in the optimal way.

The amplification may spark further lines of investigation, more verification and amplification until the issue is saturated in what Bellingcat calls an “IVA loop”. OSI is now in use across the UK national news media.

Perhaps the most high-profile example is BBC Verify, launched by the British public broadcaster in May 2023 in response to concerns about “disinformation” and declining trust in news.

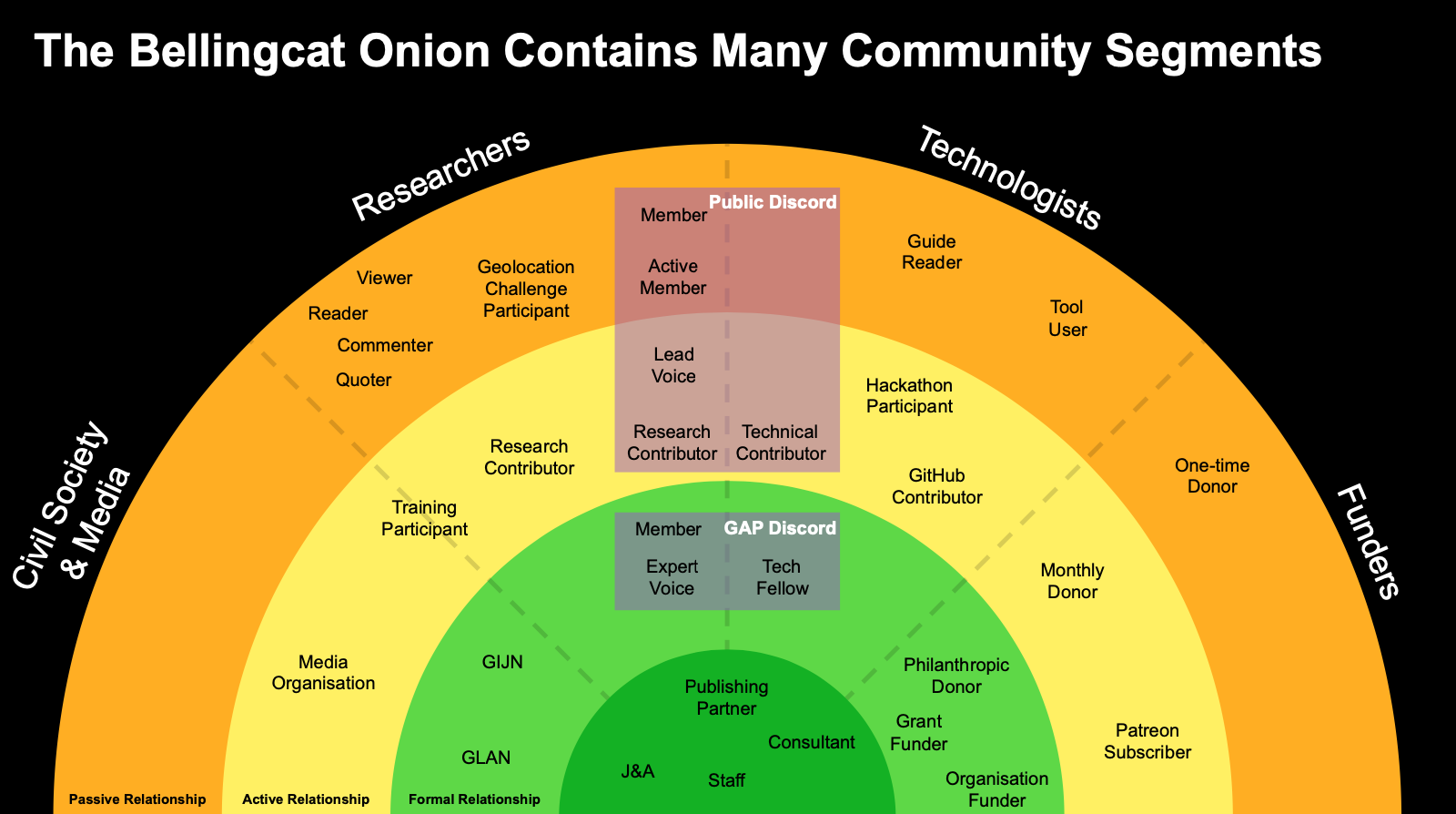

As for Bellingcat, what began in 2014 as a volunteer cooperative of individuals within the nascent global OSI community has expanded into a core of approximately 40 staff members, and a worldwide volunteer community at varying levels of engagement characterised by the so-called ‘Bellingcat onion’. Within the spectrum of engagement characterised by the “onion” there are different roles:

- Civil society and media

- Researchers

- Technologists

- Funders

Each role has people at the core, for whom it is a full-time job, all the way through to people who contribute their time or money rarely or as a one-off.

However, whilst the organisation has expanded in this way, it has maintained the IVA loop modus operandi across the rings of the onion and the roles within it.

How to broaden the ‘Bellingcat onion’

Given the difficulties of fact-checking and regulation, it is suggested instead to broaden the “onion” through empowerment of news consumers with OSI skills and mindset. They could join the outer rings of Bellingcat, contribute to local news or just act as individuals.

The key is that such empowerment with critical thinking and basic investigation moves news consumers beyond the cynical trust-in-nothing nihilism of “fake news” and “post-truth” to the discerning critique of stories at source – and the development of new ones. It is necessary because technological advances mean the usual publishing gatekeepers – journalists and editors – are no longer in charge.

If anyone with a smartphone can publish, they should also be able to verify. To combat any security threat posed by disordered information we need to teach young people these skills. Then we’ll empower them to think independently, question sources and understand the complexity of the endless information available on the internet.

Encouraging this mindset also has the potential to feed into the journalism pipeline at the local level and beyond. OSI can be applied to local and hyper local issues as much as national and international. This could help people shake off the idea that politics is something which happens to them and encourage more participation in civic life. It could also make them less susceptible to the rabbit hole of conspiracy theories.

Bellingcat has worked on similar projects before with the Student View organisation in the UK. What is proposed therefore is the updating of media literacy initiatives to include OSI skills which encourage and enable individuals to take responsibility for the news they consume – and perhaps identify and investigate their own issues.

This is an ambitious proposal to introduce verification skills into the UK education system. It focusses on younger generations because they have more access to education and may be more willing to embrace the technical skills required. Advanced Bellingcat-style investigations are obviously not appropriate for under-18s – but basic investigations focused on local issues are. Such skills could be embedded into the curriculum or be extra-curricular encouragement of student-run newsletters and pop-up newsrooms.

Similar ventures at a higher level of engagement with OSI could apply to further education colleges and universities can run modules teaching full OSI analysis and applications. This has already been done by a team led by Dr. Brianne McGonigle at Utrecht University, which established the Global Justice Investigations Lab in 2023. Students at GJIL have used OSI training to investigate attacks by various government forces on journalists covering protests and collected evidence of Russian breaches of human rights law in Syria.

An undergraduate module is due to start at the University of Nottingham’s School of Politics and IR in Autumn 2025 which will include practical OSI skills, underlying theory and applications in journalism, law and policing/security. It is hoped this will be extended to other areas of the university – law, media studies – and into Masters and PhD level programmes.

There is also scope for a pilot project in local schools and colleges. The goal is to foster skills which would enable young people and students to engage in an elementary identify/verify/amplify loop in their own communities – and feed into local mainstream media or the outer rings of the ‘Bellingcat onion’ boosting participatory democracy.

Ultimately, this is not optional. It is a necessary policy which requires government backing to counter the impact of disordered information on the UK.

Conclusion

We have argued there is a clear but multifaceted jeopardy facing liberal democracies from disordered information which can be weaponised by home-grown and foreign actors to influence narratives sustaining illiberal governments elsewhere and using it as a foreign policy tool on their soil.

Perpetrators are usually states although non-state-actors are also responsible. Countering such influences is hard for a number of reasons. Illiberal intent is shielded by the liberal “veneer” and use of proxies. Trust in liberal institutions such as news has declined in recent years. Younger people increasingly consume news through the hard-to-regulate environment of social media – and AI has already boosted the capability of bad actors to produce more content, more quickly.

Such hi-tech, post-truth conditions call for radical solutions. It is no longer possible to tell news-consumers what is true or false as they are less open to suggestion – and may also be consuming news elsewhere.

However, the freedom they enjoy includes the responsibility to question – and verify if necessary. The Bellingcat OSI model can be taught in schools, colleges and university settings to facilitate this and change the mindset of news consumers from passive to active. This will enable them to avoid either believing false information to be true or believing all information to be false. It is essential to give the next generation the skills to distinguish truth from chaos.

Eliot Higgins is Bellingcat's founder and Dr. Natalie Martin is co-director of the Centre for Media, Politics and Communication Research, and Assistant Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Nottingham.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time