How a global media company can succeed in India

Over the past 15 years I have worked with leading international and homegrown brands in India. As I helped them launch, expand and restructure their businesses in my home country, it has been fascinating to observe how similar and repetitive their decisions and strategies were.

The digital revolution is disrupting every aspect of media companies. When forging partnerships and expanding to new markets, innovation should be the very core of strategy. This article is an attempt to dissect best practices and common mistakes that managers make while designing their strategies for the Indian market.

The Indian market

Before we get into what really does and does not work, first let’s paint a comprehensive picture of the Indian media market today.

The Indian media industry, like the country itself, is multi-layered, multi-hued and unique. The Indian media and entertainment sector reached $23.9 billion, a growth of 13.4% over 2017. With this current trajectory, it is estimated to grow to $33.6 billion by 2021. While digital media is the fastest growing segment, it currently comprises only 15% of the total media pie compared to the global 51.4%.

With about 1.3 billion people, India has reached a mobile penetration of 91% households across India, with 1.7 bn mobile connections and 776 million unique subscribers. 66% of the total mobile screens are smartphones. And 85% of these are using the Android platform. The adoption of mobile and wireless internet has been driven by access to five things:

-

Affordable handsets at price points of $20 – $30.

-

Reduced tariffs of mobile data since 2016 with entry of Jio Telecom. In India mobile data charges are as low as $0.05 per GB.

-

Improved connectivity in rural areas.

-

Technology innovations: voice search and language keyboards.

-

Growing content ecosystem: rise of content platforms and telco content bundles.

India now boasts of approximately 540 million internet subscribers. 90% access the web through wireless devices. Mobile is now the primary screen in India. This is disrupting media consumption patterns as it has created an ecosystem for personalised single-user entertainment. India has the second largest population of internet users and the highest per capita video consumption in the world, reaching 10.7 GB per user per month.

The first 200–250 million internet users in India can be described with three Ms: Male, Metro and Millennials. You can say that this set was largely English-first. However, as digital media breaks new ground and targets new segments, we observe a new pattern of consumption online across languages, genres and formats. This new set of users are coming from Tier 2-3 cities and rural areas. Many of them are women and their consumption is described with three Vs: Voice, Video and Vernacular.

The Ernst & Young India Media Report 2019 states that 90% of the content watched on YouTube in India is produced in regional languages like Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Bengali, Punjabi and Marathi.

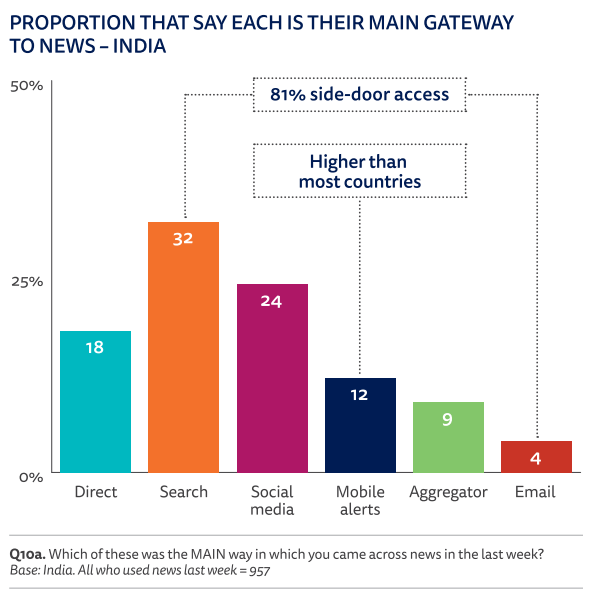

The India Digital News Report, published by Reuters Institute in 2019, found that 68% of the respondents identify smartphones as their main device for online news, 31% say they only use mobile devices for accessing online news. These figures are markedly higher than in other markets, including developing markets like Brazil and Turkey. Around 52% of the respondents said that they got their news from Facebook and WhatsApp. According to Appannie.com’s data released in June 2019, six out of the top 10 apps are news aggregators, with platforms like Twitter and Daily Hunt taking the lead.

Even strong media brands find that 60% to 85% of their traffic comes from social platforms and aggregators. This trend is more acute for social and entertainment content, which relies on virality and shares for reach.

India is an attractive market for global media players. The reasons are its massive size and its open market policies for digital players. However, these companies won’t succeed unless they follow a different playbook. Sharp segmentation is the key to success.

If a company wants to come into India without making any changes in content creation, pricing or distribution, it will only be able to capture the top 1% of the Indian consumers who are highly affluent and are exposed to the same influences as their western audiences

Any product or service that works globally will only work for the top 1% of the market in India. If a company wants to come into India without any localisation (i.e. changes made in content creation, pricing and/or distribution of their products), then it will only be able to capture the top 1% of the Indian consumers who are highly affluent and are exposed to the same influences as their western audiences. For instance; international publications like The Economist, the Washington Post and The New York Times. All these publications create either one single global edition (The Economist) or at best two editions (one local for the US market and one international). They are not aiming to create local solutions for each market where they operate. Their content and pricing do not vary dramatically across markets. As a result, they target only a small portion of the audiences in India.

To capture the next 5% to 10%, a company needs localisation in terms of content, pricing and distribution. Let’s take what happened to Netflix in India as an example. With its heavy investment in marketing and limited local content library, it was able to capture 500,000 subscriptions by focusing on the top 1% of the market. However, earlier this year, Netflix launched a new mobile-only tariff plan at about 40% of its initial base price. Reed Hastings recently announced that Netflix is investing $422 million in 2019-20 towards content creation in India.

Don’t make these mistakes

Here are a few common mistakes international companies still make while entering the Indian market.

-

Setting the wrong metrics. One of the primary reasons international businesses fail when entering emerging markets is that they apply the same metrics they use in the home countries without understanding the local market ecosystem.

-

Entrusting mid-level managers or people who have limited understanding of the regional market to assess and create market-entry strategy.

-

Not undertaking a cultural due diligence of local partners before investing and creating a corporate structure.

-

Not customising their product, service, audience set, pricing or brand to the Indian market. Companies often invest in local content creation. However, their language, templates and context remain broadly international. This is often limiting in the brand’s relevance and reach in India, which continues to be influenced by its local culture and religion. Let’s take the example of HuffPost. It came to India in 2016 in a joint venture with The Times of India. On one hand, its content was locally led and produced by a small editorial team. On the other hand, its UX and its templates were the ones of the international product. This created a sub-optimal product for India. While HuffPost got revenue through its licensing deal, it left the local player in charge of understanding audiences and catering to their local needs, without any access to audience data or authority to customise the user experience.

-

Not empowering local executives, thus limiting market adaptability and on-ground agility to do business in the local country.

-

Not investing in creating value for the long term. Driven by their global strategy, many companies are focused primarily on their annual profits and losses and demonstrate a limited investment appetite for capturing local market opportunities. A leading youth media company launched in India with the goal of becoming a leading media company in the country. However, it was relying on its existing brand equity globally to capture the market, rather than actually investing in building its brand locally. This was inadequate for three reasons. Firstly, the company didn’t invest enough in local content creation. Secondly, it chose not to build or customise its digital platform to suit the Indian audiences and tech infrastructure. Thirdly, it did not invest in building brand awareness through advertising amongst local audiences. These decisions led to the company restructuring its model in India and focusing on being an agency and a B2B content provider rather than a youth media platform.

If global companies want to succeed in India, it is critical for them to segment their audience and assess this opportunity as different ‘market sets’. If the objective is to monetise, partnerships will remain a critical route for international brands with no customisation or operational involvement in the Indian digital ecosystem. To capture the massive Indian audience, a company will need to operate in India, evolve for the Indian audience and take a long-term positioning in the market i.e. invest to educate and grow the market before becoming profitable.

Here are a few factors that have contributed to the success of global players in India:

-

Investing disproportionately in local content creation.

-

Investing in technology for high quality user experience and distribution.

-

Creating a powerful local leadership team with autonomy and authority to drive the business.

-

Focusing on long term value creation; evolving local revenue models designed for the Indian market.

-

Forging long-term partnerships with culturally aligned partners.

If a company really decides to be a mass brand, then it must operate through a completely local model. This will require taking a long-term view of value creation as companies such as 21st Century Fox (now Walt Disney), BBC and Google have done.

In my interviews with Indu Shekhar Sinha at BBC, I learnt that 2018 witnessed a 40% growth in digital news consumers over 2017 when around 180 million people consumed news online. However, except for the BBC, international media companies haven’t benefited from this rise. The BBC has seen its audience rise from 28 million monthly users in 2018 to 50 million in 2019 after investing in local news creation in four additional regional languages (in addition to English and Hindi), building partnerships with TV broadcasters, and localising their digital distribution through platforms like Dailyhunt and WhatsApp.

Digital partnerships

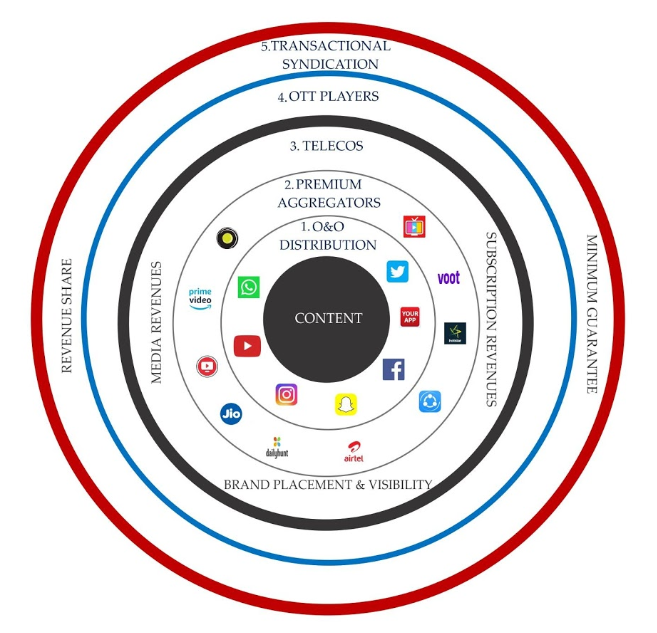

What international media companies really need today is to forge partnerships with a few strong players who can help them distribute or syndicate their content to relevant audiences, with meaningful engagement and monetisation across the users’ multiple touch-points in their digital journeys.

The Indian government only allowed international players to get a minority stake in print and TV news media companies. These players worked with a local partner in order to have access to their production and distribution infrastructure, to manage local regulation and labour laws, and to be able to reach advertisers.

In the digital platform ecosystem, international players haven’t faced any restrictions in e-commerce, news or entertainment until 2019. This resulted in technology platform companies leading on market development in the digital ecosystem.

This is obvious from the apparent dominance of international platform companies in India across social, entertainment and messaging platforms. These platforms have invested heavily in market development through:

-

Personalisation of user experience to cater to a heterogeneous market base.

-

Multilingual interface with up to 12 languages supported for some platforms.

-

Creating revenue models for the local market and investing in education the advertisers and the consumers.

-

Innovations in format for enabling access to low-end smartphones and feature phones and low bandwidth access solutions.

The primary sources of traffic for most news publishers are social, messaging apps, news aggregators and apps created by telephone companies. For a comprehensive digital presence today, publishers have to approach the audience through multiple touch-points across platforms.

News companies face many challenges in this new ecosystem. The policies of the platforms curtail their journalistic independence. The access to their audience depends on their algorithms and they are forced to pay to get eyeballs. In this kind of environment, it’s difficult to charge for a subscription and advertising is not easy to monetise. So it is important for media companies to forge long term partnerships with fewer platforms and develop a mutually beneficial relationship allowing editorial control and enabling monetisation of the content.

This exhibit articulates the complexity of a digital distribution network required to build reach and engagement. All specific companies mentioned here are for reference only and not intended to be exhaustive. Strategies for each company will depend on their content genre, format, intended audience and monetisation strategies.

Questions to ask before investing

In conclusion, to choose a long-term partner in India, one must undertake a thorough cultural assessment beyond just business parameters. Here are some of the questions that any executive from a global media company should ask before making any decisions:

-

What are the business plans of our partners and its relevance to our product or our service?

-

How does our brand fit into their business plan? How important will our service be to them?

-

What is the current market share and quality of platform of our partner?

-

Can we map the history or the reputation of this company with international or domestic partnerships?

-

Can we ascertain their willingness to invest in promotion of our brand?

-

Is there any conflict of interest between their portfolio of companies and your brand?

-

Can we establish the influence of the existing networks and relationships of our own company with their investors or promoters?

Complexities aside, the Indian media industry should be assessed, explored, tackled through the twin pillars of numbers (i.e. large market) and local culture (i.e. diversity, ethos, demography, literacy, lifestyle). The nature of partnerships will continue to evolve given the fluid regulatory environment and the nascent subscription ecosystem. However, any global company willing to succeed in India should reassess and reimagine this business opportunity with a fresh perspective on localisation of management, content, business models, metrics and partnerships. Otherwise, they will fail and dilute the value of their brand.

____

Chanpreet Arora is a recognized leader in the Indian Media Industry. She is currently an independent consultant and is advising New York Times on scaling their subscription business in India. Earlier she led the team as CEO for launch of VICE as a full-scale media company in India. She recently wsa a Journalist Fellow at the Reuters Institute. You can find her paper in this link.