How AI-generated disinformation might impact this year’s elections and how journalists should report on it

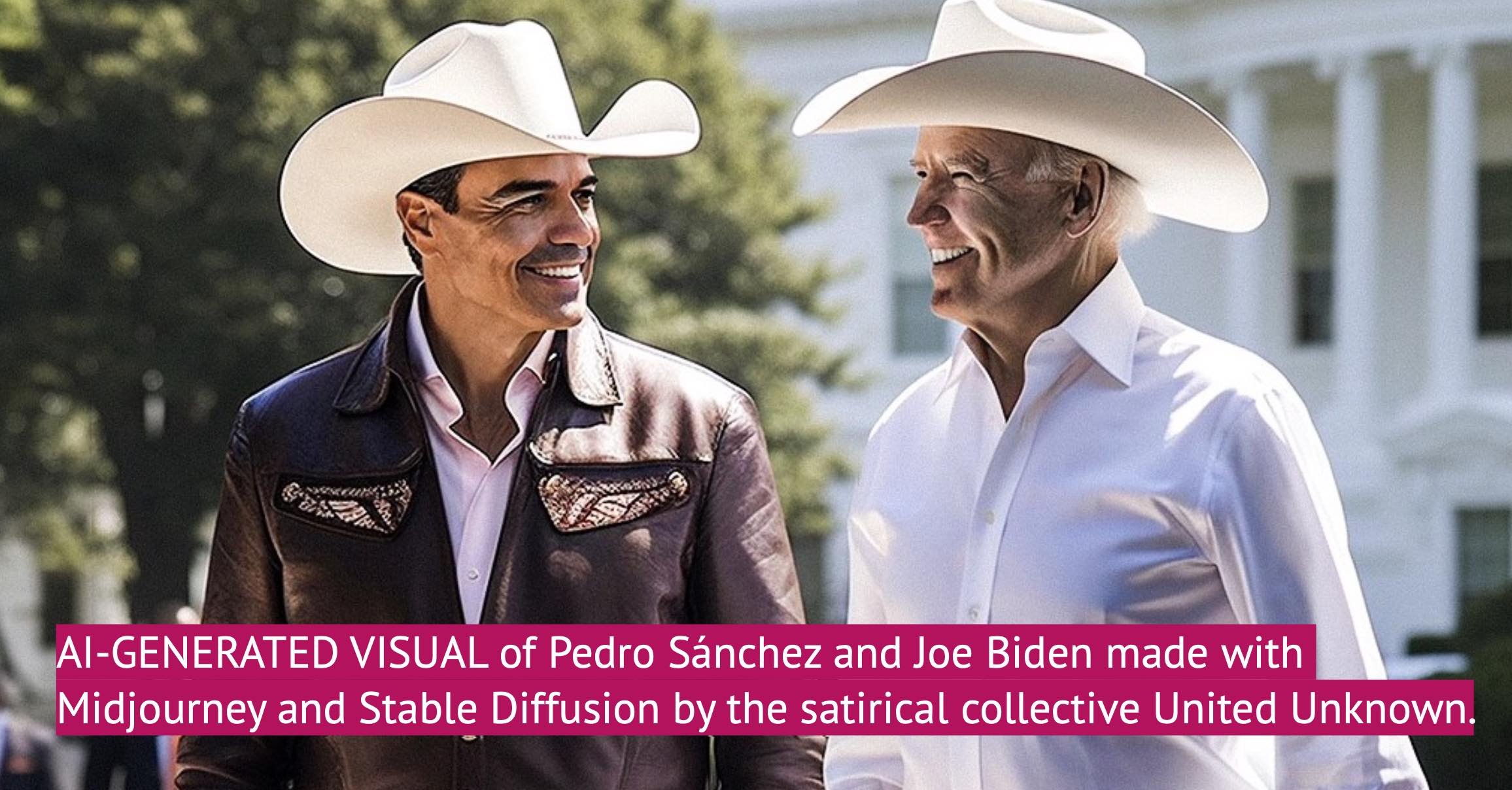

AI-GENERATED VISUAL of Pedro Sánchez and Joe Biden made with Midjourney and Stable Diffusion by the satirical collective United Unknown.

A phone call from the US president, covert recordings of politicians, false video clips of newsreaders, and surprising photographs of celebrities. A wide array of media can now be generated or altered with artificial intelligence, sometimes mimicking real people, often very convincingly.

These kinds of deepfakes are cropping up on the internet, particularly on social media. AI-generated fake intimate images of pop star Taylor Swift recently led to X temporarily blocking all searches of the singer. And it’s not just celebrities whose likeness is faked: deepfakes of news presenters and politicians are also making the rounds.

In a year in which around 2 billion people are eligible to vote in 50 elections, can AI-generated disinformation impact democratic outcomes? And how is this going to affect journalists reporting on the campaigns? I contacted journalists and experts from Spain, Mexico and India to find out.

The issue

If we were to take a snapshot of the deepfakes circulating in recent months, we would find a range of individuals whose likenesses have been faked, for a range of aims. Popular targets are those with abundant examples of their (real) appearance and voice available online: celebrities, newsreaders, politicians. The purpose of these fakes ranges from satire to scams to disinformation.

Politicians have appeared in deepfakes peddling financial scams. The UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, for example, was impersonated in a range of video ads which appeared on Facebook, as have TV newsreaders, whose image is often used to advertise fake ‘investment opportunities’, sometimes involving celebrities who may have also been faked.

There have also been examples of deepfakes of politicians to achieve a political outcome, including some election-related ones. An early example was a (quite unconvincing) video showing a clone of Ukraine’s President Volodímir Zelensky calling for his troops to lay down their arms only days into the Russian full-scale invasion.

A high-profile and higher-quality recent example was an AI-generated audio message of a fake Joe Biden attempting to dissuade people from voting in the New Hampshire primaries. Another example was a video of Muhammad Basharat Raja, a candidate in Pakistan’s elections, altered to tell voters to boycott the vote.

AI for satire: a view from Spain

Creating AI-generated images has never been easier. With popular and easily accessible tools such as Midjourney, OpenAI’s DALL-E and Microsoft’s Copilot Designer, users can obtain images for their prompts in a matter of seconds. However, AI platforms have put in place some parameters to limit the use of their product.

DALL-E doesn’t allow users to create images of real people and Microsoft’s option prohibits ‘deceptive impersonation.’ Midjourney only mentions ‘offensive or inflammatory images of celebrities or public figures’ as examples of content that would breach its community guidelines. Violent and pornographic images are also barred from all of these platforms.

Other tools do allow for a wider range of creation and some people are using them. Spanish collective United Unknown describes itself as a group of ‘visual guerrilla, video and image creators.’ They use deepfakes to create satirical images. They often portray politicians, as in the images in this piece published by Rodrigo Terrasa at El Mundo.

United Unknown’s creations are very realistic, but there’s something in their definition that identifies them as not quite right. The content is often outlandish, such as this series of images depicting Spanish politicians as wrestlers.

Even the more believable pictures have an absurd element that characterises them as satire, such as this series of pictures, labelled by United Unknown as “an alternative, and totally false report of the meeting between [Spanish Prime Minister] Pedro Sánchez and Joe Biden.” The report opens with a typical summit picture of Biden and Sánchez posing outside the White House in near-identical suits. It quickly descends into comedy, showing the two in cowboy outfits and giddily driving around in a golf cart.

A member of the collective who introduced himself as ‘Sergey’ told me that United Unknown uses Stable Diffusion, a tool by Stability AI. Stable Diffusion is so far the only one among the main AI image generators that is open-source, meaning its models can be downloaded and modified, allowing users more freedom in what and who they can depict.

“It is already very easy, and it will be even easier in the very near future” to use AI tools to generate a fake image realistic enough to fool people, Sergey said. “In just one year the generators have gone from generating very poor quality images, with unrecognisable people, to achieving a photo-realistic result.”

Sergey admitted that some of the collective’s more ‘neutral’ images have been mistaken as real photographs. But he stressed they try to avoid this from happening: “We work in the field of political satire. We try to make critical humour. There is no intention to use the image to deceive.”

Asked about his fears around AI misuse, Sergey stressed the responsibility and intentions of the user over specific concerns about new tools. “The responsibility always lies with the author-creator-ideologist, not with the technology used,” Sergey said.

“Artificial intelligence generates images from our instructions,” he explained. “The results we get are mainly based on our requests but also the knowledge acquired by the models. They replicate, reproduce and even amplify our own values, prejudices, errors and biases. They offer us an image that is a reflection of the idea of us, of the society in which we live and its inequalities.”

AI and elections: India and Mexico

AI-generated images and videos represent a potential danger in the context of elections. But some, including the BBC’s disinformation reporter Marianna Spring, are more concerned about audio and its role in disinformation this year.

Mexico’s general elections will be held in early June. According to Arturo Daen, editor of the fact-checking section of the political news site Animal Político, traditional disinformation around the vote is much more prevalent than AI-generated disinformation. But Daen described an audio clip purportedly recorded by the head of government in Mexico City, Martí Batres, expressing a preference for one of the mayoral candidates.

In the audio, the fake Batres says he wishes to promote one of the candidates, Clara Brugada and gives instructions to work against her rival. Batres claimed the recording was an AI-generated fake.

“We analysed the material and different tools could not identify with precision if this technology was actually used,” Daen said. “The case generated alarm for the possible proliferation of this kind of audio and the difficulty of verifying them. Since then, however, we have not encountered more of this type of material, at least at that scale or level of impact.”

A potential new danger of AI-generated disinformation, according to Mexican political scientist Jorge Buendía, stems from the fact that it can be used to convincingly impersonate politicians, and use their image or voice to spread falsehoods among their own supporters.

An example of this is the fake Biden phone call cited above, which was used to target Democrat voters in the US. “In communication theory, there is this principle that who the messenger is matters a lot,” Buendía said. “AI has the potential to make people believe that the messenger is trustworthy, and that can be a game changer. What we have found in the past is that people will resist the messages that are expressed by people that they don't like. But here the messages are going to be supposedly delivered by people they trust.”

Joe Biden is not the only world leader whose voice has been imitated in this way. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s voice is also commonly reproduced with AI tools, both as a campaigning tool by his party and for satirical purposes, said Indian independent journalist Srishti Jaswal.

While reporting on politics, tech and human rights for various outlets, Jaswal is a Pulitzer Center 2023 AI Accountability Fellow. As part of the fellowship, which runs from September 2023 to July 2024, she is investigating the impact of AI technologies on Indian elections.

AI fake audios and videos have also emerged in India ahead of the upcoming general election, with an example being videos of Manoj Tiwari, a member of parliament for the ruling BJP, addressing audiences in three languages: Hindi, Haryanvi and English. According to Al Jazeera, the Hindi video was genuine and the other two had the audio and video altered using AI to reach audiences who speak those languages.

On the other hand, AI is also being used on social media for humour, such as to imitate Modi singing songs. “It has become an epidemic,” Jaswal said. “Wherever you go, you see Modi's voice being imitated almost everywhere.”

Part of the risk in Mexico is the high percentage of people without formal education, which often leads to problems in identifying mis- and disinformation, Buendía said. A similar issue exists in India. Jaswal pointed out that the disparity between India’s internet penetration and the population’s literacy rate could lead to more people not having the tools to understand these nuances.

“In cases like that, automation and AI can become a very fast and very furious tool to influence people en masse,” she said.

A weapon against women

Jaswal gave another recent example of the use of AI in the context of politics. In 2023 an AI-manipulated image was used to discredit female wrestlers protesting against the President of the Federation of Wrestling, who is also an MP for India’s ruling BJP party and whom they accused of sexual harassment.

Two of the protesters took a selfie while being arrested to see who had been detained along with them. While in the original photo, the women look serious, a manipulated version of the image started circulating on social media showing them with broad smiles. “This actually discredited the protesters. [People said] how are they happy about this entire thing?” Jaswal said.

Jaswal believes AI might also convince Indian women to shy away from speaking openly about their political views.

“Many women have seen that [AI] has been used to generate photographs of them in sexual positions, which is very objectionable in a patriarchal society like this,” said Jaswal, who thinks that some women may choose to step back from being in the public eye in the face of this threat. Bollywood actresses went through these kinds of attacks in November 2023.

According to Jaswal, deepfakes are often created by young people looking to go viral and monetise their content and are not so much part of the strategy of organised political campaigns. For young people who are unemployed and facing a rising cost of living, social media can seem like an attractive place to make some money.

Another reason an individual might generate fake content is a real feeling of contempt towards women, journalists or Muslims, groups that often face intense discrimination, Jaswal noted. Whereas these attitudes are often encouraged by politicians, the people creating and posting targeted faked content often act independently.

How different is AI-generated disinformation?

“The manipulation of information is not new, nor are image montages,” Sergey from United Unknown said. “The media, the technology and the tools change. Are we facing the democratisation of the false and artificial image? We should not be concerned about the technology itself but about its use, and the intentions with which it is used.”

This attitude is shared by others in the AI field. In a commentary article published in October 2023, researchers Felix Simon, Sacha Altay and Hugo Mercier argue that concerns about AI worsening the problem of misinformation are overblown.

AI may increase the quantity of misinformation, they write, but this won’t necessarily mean people consume more of it because of limits to demand for misinformation, which is already abundant. Even if it does increase the quality of misinformation, that may not have a great impact on audiences either, as there are already non-AI tools available that can make fake images look realistic. Moreover, persuasion is difficult, so even high-quality personalised disinformation would likely have a limited impact.

Regular disinformation is still a greater concern than AI-generated disinformation for the experts I spoke to: Buendía echoed the idea that “negative campaigning, exacerbating people's prejudices and beliefs, has been around for centuries.” The only meaningful change, he said, is in the way people receive this disinformation.

Buendía doesn’t think this year’s elections in Mexico will see much AI-generated disinformation. “It’s probably too soon,” he said. Jaswal made a similar assessment about her country: “I still feel that the use of AI in Indian elections is at a very nascent stage,” she said, adding that, with time, we could see more complex situations.

How journalists should address this new threat

Daen wishes fact-checkers could have access to more powerful tools to tell with certainty whether a recording has been deepfaked or not. In the absence of these tools, journalists have to delve into the context of the disputed piece of content, looking at where it first cropped up, which accounts shared it and what kind of content they usually share.

“AI has made us more cautious,” he said. “When saying if a material is fake or not, we turn to a deeper investigation before giving a verdict.” This is particularly important in the context of an election campaign.

“I believe it is important to insist on investigations on who is behind disinformation, which agencies or political parties,” Daen said. “With El Sabueso [Animal Politico’s fact-checking vertical] we have published different reports on disinformation networks, coordinated actions with the aim of disinformation, and we will continue this job during the ongoing electoral process.”

In the meantime, AI companies and social media platforms are aware they are under scrutiny. On 16 February, at the Munich Security Conference, 22 of these companies, including tech giants Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Meta as well as AI developers and social platforms signed on to a joint statement which pledged to address risks to democracy this year of elections. The document lists several ‘steps’ towards this, including helping to identify AI-generated content, detect their distribution, and address it “in a manner consistent with principles of free expression and safety,” but lacks any tangible targets.

Jaswal advises journalists to keep reporting on any further developments. “With such sinister new technology being used, it takes time,” she says. "As a journalist reporting, my only approach is to be observant, and I'm observing everything.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time