Echoes from the desert: Five seasoned reporters reflect on the vanishing landscape of local news

A man looks at newspapers at a vendor's stand in Lagos. REUTERS/Akintunde Akinleye

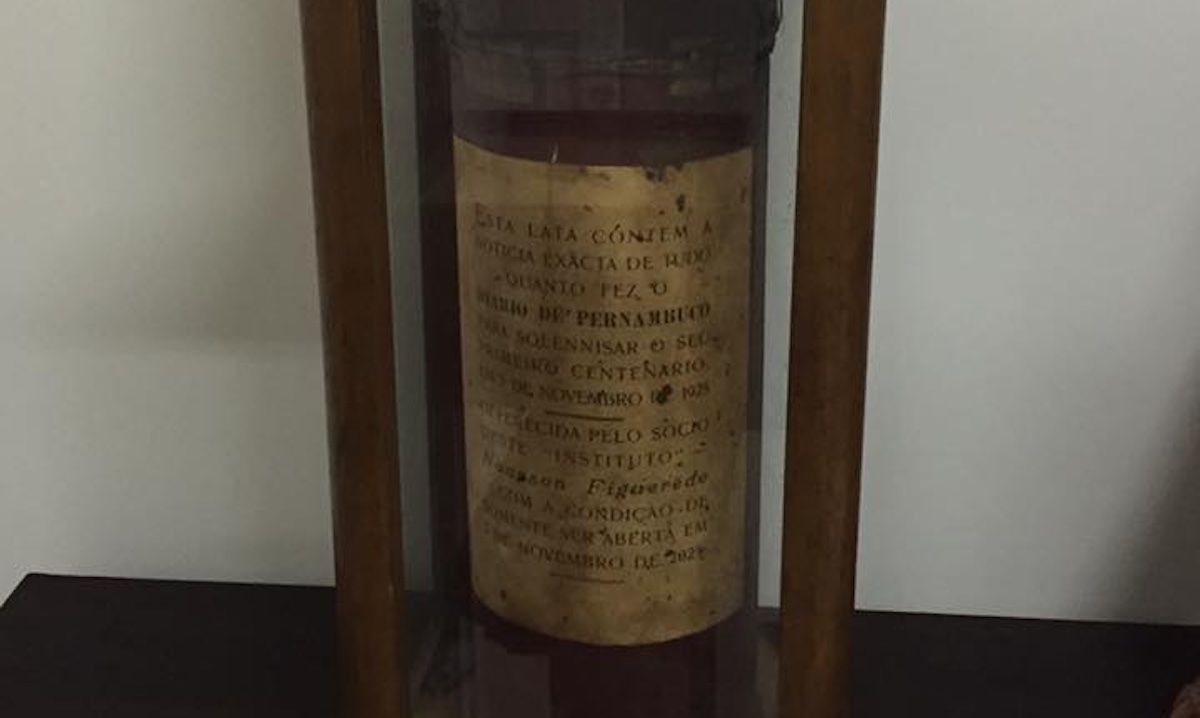

On 7 November 2025 Latin America's oldest daily newspaper still in circulation is scheduled to open a time capsule stored in a museum in Recife, a city in the northeast of Brazil. On that date the Diário de Pernambuco will mark its 200th anniversary. At the ceremony journalists and editors will see objects and read messages placed in the capsule in 1925, the year the newspaper celebrated its first century of life.

Despite the symbolic importance of the event, there won't be much to celebrate. In the midst of a severe financial crisis, Diário de Pernambuco is now a shadow of its glorious past. Waves of layoffs have reduced the newsroom to a tiny fraction of what it once was. Those who remain live with a routine of pay delays that sometimes exceed three months. Coverage of local issues has been radically slashed.

A report on local journalism in the US released earlier this year by the Medill Local News Initiative presents a similar picture, and one that renowned journalist Steve Waldman described as "the most alarming" he has ever seen. According to the report, newspapers are vanishing at an average rate of more than two a week. The data shows that 2,900 local newspapers have disappeared from the country since 2005. Many countries around the world are going through the same process.

In Brazil, a survey conducted by a project called Atlas da Notícia shows that 942 news organisations have shut down since 2019. Local newspapers and magazines account for more than half of these closures, according to the most recent report.

So-called news deserts are nothing new. Digital disruption has been especially brutal with local and regional newsrooms. Many have vanished or lost their relevance or their soul. In this article, experienced reporters from four continents speak about the state of local journalism in their countries, share their memories about past endeavours and try to imagine what the future may have in store.

Memories from a different past

Daniel Golden, a senior editor at ProPublica, recently wrote a piece on how the town of Ware, in the American state of Massachusetts, is becoming a news desert. Important decisions for the future of the community, such as the privatisation of water and sewer services, for example, are being made with little or no oversight from the local press, which has almost entirely vanished.

The Springfield Daily News, the newspaper Golden worked for in the early 1980s, no longer exists. He remembers how the publication used to cover the region quite well and had a correspondent assigned to keep a close eye on what was happening in Ware. Today, people feel forgotten by the news media. In the absence of real journalism, all that’s left is pure speculation on Facebook.

In a conversation for this article, Golden shared memories from his days at the Springfield Daily News that sounded premonitory. “One of my colleagues, Steve Gield, created a beat out of covering neighbourhood meetings so insignificant and obscure that nobody had considered them newsworthy before,” he says. “Eventually, Steve took a job at another newspaper. On his last day, he told one of these groups that he was leaving. They asked who at the Daily News would be his replacement. Steve said, ‘Not only will I not be covering your meetings any more, but nobody will ever cover them again.’”

The view from Brazil, Nigeria and France

A reporter and columnist for Diário de Pernambuco for more than 20 years, Marisa Gibson remembers the strength and scale of the newspaper's regional coverage in the past. During the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985), she says, when the press was under censorship, smaller local newspapers were able to bypass the censors' surveillance and publish information that was important for the community.

“Today we live here just with national news. We often only hear on Monday about something important that happened over the weekend. That's because the local TV programmes, which still survive, aren't aired on the weekend. Unless it's something very extraordinary, the local papers simply don't cover it,” says Gibson, who was fired during the pandemic without even receiving the money she was entitled to receive.

In Europe, the crisis has significantly reduced the circulation and the editorial staff of Le Progrès, a daily newspaper covering the region around the French city of Lyon. Christian Lanier, who’s worked as a reporter for the publication since 1986, says that the newsroom has already been downsized by around 30%. “This has affected our correspondents in small towns and villages, who are the intellectual strength of the newspaper,” he explains.

Lanier considers the 1960s and 1970s to be the heyday of regional journalism in his city. During this period, he recalls, there was another newspaper, Le Progrès Noir, distributed in the evenings in the city's streets, cafés and restaurants. The newspaper played a decisive role in the famous case of the "Lyonnais Gang", which carried out dozens of armed robberies, and in the trial of Klaus Barbie, a Nazi officer based in Lyon who was responsible for the deportation of thousands of people to Germany.

The gaps in crucial information left by the weakening of local news organisations are also evident in Africa. Nigerian journalist Obas Esiedesa reports that the effects of repeated vandalism and oil theft in the Niger Delta region are not sufficiently publicised by the local press.

“Oil pollution is a major challenge here as rivers and farmlands are polluted by oil spills, pushing fishermen and farmers out of their main source of livelihoods,” Esiedesa says. For years he worked at the Niger Delta Inquirer, a daily newspaper that covered the southern region of the country. The publication closed its operations in 2011 due to management problems and the struggle to break even.

Unlike colleagues in other countries, Esiedesa considers the 2000s to be the heyday of journalism in his region. This was the time when Nigeria became a democracy again and this created space for professional journalism to flourish. “It was a huge and significant period for our country,” he says.

The effect on editorial independence

How do financial struggles affect editorial independence and the ability to report on local powerful figures? A paper I wrote in 2019 for the Reuters Institute shows how politicians have captured the best reporters in Recife in recent years.

“Funding at the regional level is a major issue,” Nigeria’s Esiedesa says. “With limited income coming from copy sales and ads, regional media houses are forced to seek political patronage, which more often than not compromises independence and quality journalism.”

In his article for ProPublica, however, Golden warns against idealising the past. The Springfield Daily News didn't always fulfil its watchdog role, he says, even during the boom times. Like “a doting father,” he writes, the newspaper paid attention to its community, but sometimes with a paternalism that chose to hide problems in the service of what it considered to be a broader good.

“The same focus that inundated readers with information about every committee meeting, crime and high school football game fostered a certain cosiness with the area’s power player,” he says. “Boosterism and conflicts of interest occasionally interfered with telling the full story. It’s possible we would have done a searching examination of a plan to privatise Ware’s water system – unless we risked offending a powerful local figure or business interest.”

Gibson, the journalist from Brazil, agrees: “The newspaper was better in the past, but we didn’t have full independence. There has always been a great deal of influence from state advertising. It’s just that the private sector was much stronger as an advertiser and today it practically doesn't exist.”

Are local reporters disappearing too?

Digital disruption is also having a strong effect on the makeup of local newsrooms. Golden recalls how regional newspapers were once considered invaluable training grounds for young journalists, “an irreplaceable mix of learning and hazing.” Things are quite different today in the view of all the journalists I interviewed for this piece.

“The way journalism is done today has changed. The regional paper is no longer the training ground it used to be. Now most news is produced at a desk by people with their eyes fixed on a computer,” says Jean-Bernard Sterne, who worked for 35 years at Midi Libre, a daily newspaper covering the Languedoc Roussillon region in the south of France, between Toulouse and Marseille.

He says the shrinking of newsrooms makes it impossible to train newcomers. “Furthermore, the professional life expectancy of a journalist working for the same newspaper today is no more than ten years. Many journalists even change jobs because the profession no longer corresponds to their original motivation,” says Sterne, who built his career on sports coverage.

He tells me that Midi Libre used to follow major national and international events. Sterne himself was a special envoy to six Olympic Games and two World Cups. Although the newspaper no longer has the money to cover these events, it still manages to follow the main local happenings, such as a national judo tournament that took place in the region or the visit of an important authority. “The problem is that this is not enough today to bring in new readers and keep them loyal to the paper,” he says.

In the northeast of Brazil, Gibson sees young reporters as too dependent on their immediate editors. She says they just follow the stories TV stations are already broadcasting. They don't look for their own stories anymore.

Golden reflects on the reasons why this has happened in the past decade: “The methods I learned – to high-tail it to a fire or shooting; to buttonhole officials before and after public meetings; to take notes in pencil outdoors in winter, because ink congeals in the cold – are becoming a lost art. The internet has created a generation of reporters who stay at their desks, gathering information on their computers or talking to people on Zoom. They aren't comfortable going out and knocking on doors.”

What’s next for local journalism?

It may seem like the end, but it's not the end yet. The Medill Local News report, which covers the US market, points to a few green shoots with both for-profit or not-for-profit news organisations flourishing without the burden of a large debt. Almost all of them are owned by local entrepreneurs and maintain large reporting teams.

When it comes to the US, Golden is betting on non-profit projects. “Some (like ProPublica, where I work) are national. But many others are springing up locally around the country, often in communities where the local newspaper has closed or is a shadow of its former self. These local nonprofits are idealistic and ambitious; they want to do in-depth, investigative journalism.”

Lanier sees a promising future for local French newspapers whose editors embrace digital while keeping the same standards of the past.

“Journalism has a great future and works very well in rural areas. At Le Progrès, the example comes from the Beaujolais area,” says the reporter, referring to the region, 50 kilometres from Lyon, famous for its grapes – and wines. According to Lanier, the newspaper he works for is very popular in this region, precisely "because it has a real social and community function.”

Esiedesa is not so enthusiastic about Nigeria, where many newsrooms are struggling financially. But he thinks shifting to digital is the only way to survive.

“Online publishing is less costly and we have seen a lot of local online outfits spring up in the past few years,” he says. “But one can also say that the cost of data and Android phones has also locked a lot of community dwellers out of the news system.”

In Brazil, Atlas da Notícia also suggests that, despite the closure of hundreds of newspapers, the launch of new digital projects has helped to reduce the number of cities considered news deserts. One of the highlights among the country's digital native newsrooms is Metrópoles, a relatively new outlet which has become the main local news outlet in Brasília, Brazil’s capital.

Despite initiatives like this, Gibson still predicts a long period of stagnation. “It's going to stay the way it is for a long time,” she says. “The news is no longer attractive. There’s no more local journalism. The government pitches the press in its own way.”

Asked if the newspaper she worked at for two decades will still be alive on the day the time capsule is opened in 2025, she bet on the publication's resilience: “Diário de Pernambuco is a newspaper that refuses to die.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time