Can news help? New evidence on the links between news use and misinformation

People light candles in the shape of a sign which reads "Solidarity" in protest against COVID-19 deniers in Munich. REUTERS/Lukas Barth

News, at its best, helps people become more informed and thus potentially more resilient to misinformation, propaganda, and other attempts to lead them astray.

As Alessandra Galloni, the editor-in-chief of Reuters, put it earlier this month, “At its best, fact-based journalism can serve as an antidote to the disinformation that clogs up social media platforms more and more”.

This observation is not just central to how many journalists and editors like to think about their work. It is also an effect of news media use known from decades of research documenting how news – despite its imperfections – demonstrably helps people be more knowledgeable about politics and public affairs.

This is especially important in a context where the informational benefits of relying on digital media, including platforms such as social media, search engines and the like, are much less clear, where much of the public is concerned about whether the information they come across online is true or false, and where misinformation clearly sometimes has wide reach on platforms including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, WhatsApp, and their smaller competitors.

But does news in fact help counter and contain misinformation problems?

We can’t simply assume that. Whatever the aims and intentions of editors and journalists, whatever you might hear in after-dinner speeches and award ceremonies, research suggests that following the news can sometimes confuse, rather than enhance, people’s factual understanding of important issues, including for example criminal justice or migration.

Some fact-checking groups and researchers fear that news coverage can sometimes, even if inadvertently, amplify misinformation, for example through attempts to debunk it, by reporting on it, or by featuring sources or guests who spread misinformation. Popular news media are sometimes hijacked by actors who use them as a way to spread false, misleading, or other forms of problematic information. In the United States, watching Fox News is correlated with belief in conspiracy theories and increased non-compliance with recommendations by health experts to practice social distancing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such concerns have led a group of prominent scholars to suggest that “mainstream media are responsible for much of the public attention fake news stories receive”. Other academics go further and hypothesise that “the origins of public misinformedness [are] more likely to lie in the content of ordinary news or in the avoidance of news altogether as they are in overt fake news” and misinformation more narrowly conceived.

So can news help when it comes to misinformation problems, or may news in fact make matters worse?

With support from the BBC World Service (as part of the Trusted News Initiative) and from the Oxford Martin School who supports the Misinformation, Science, and Media project at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, I am working with my colleagues Sacha Altay and Richard Fletcher to understand this better, looking at three very different case countries – Brazil, India, and the United Kingdom.

In this post, I summarise the preliminary results from our work (not yet through academic peer review), which I presented at the 2022 Trust in News Conference organised by the BBC Academy. Those interested in the full working paper can read it here.

While results are not identical across the three countries, nor consistent for all types of news use, overall, we find that news can help.

In two of the three countries covered, news use broadens people’s awareness of false claims without simultaneously increasing the likelihood that they will be believed, and in one country news use clearly weakens belief in false claims (while also, as much previous work has found, in many cases increasing political knowledge).

In contrast, with some important exceptions, most forms of digital platform use have no significant effect on either awareness of or belief in false claims about COVID-19, or on political knowledge.

The findings are based on a two-wave panel survey conducted across the three countries in early January 2022 and again, with the same people re-contacted in early February. Samples were assembled using nationally representative quotas for age, gender, education and region in all three countries. (Because Internet penetration is relatively low in Brazil and India, samples are more representative of the online population, which in turn is more educated and affluent than the national population – and in India the survey was fielded in English only, meaning that the survey is, at best, representative of the online, English-speaking population only.)

So what have we learned about the relationship between news use and respectively political knowledge, awareness of misinformation, and belief in misinformation?

Let’s look at political knowledge first, because the news media may well argue that their main role is to help people become more informed.

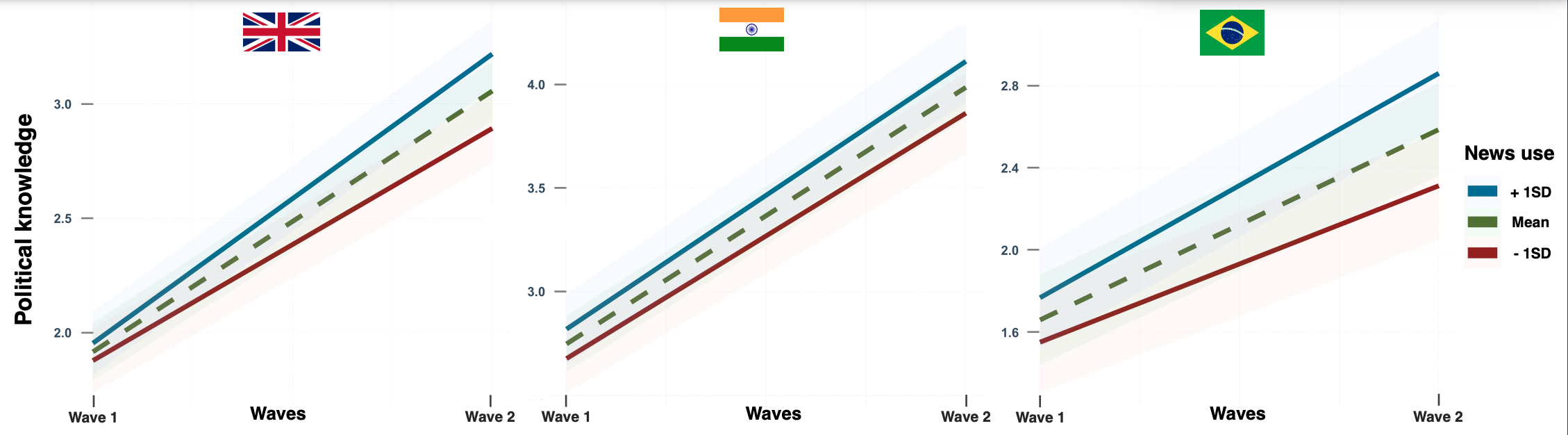

The figure below shows political knowledge gains between wave 1 and wave 2 as a function of news use. In wave 2 we added new questions about political knowledge referring to events that happened after wave 1. The green dotted lines represent political knowledge gains for participants with average levels of news use, while the solid blue line for one standard deviation above the average news use, and the solid red line for participants with news use one standard deviation below the average. Because we asked more knowledge questions in wave 2, we are not interested in the increase between waves, but in differences in the size of the increase for different groups, reflected in the steepness of the lines. This difference is statistically significant in Brazil and the United Kingdom, and aligned with existing research – news use helps people acquire political knowledge.

What about awareness of false and misleading claims then? (We focused on claims about COVID-19, and it is important to note that our findings may not necessarily generalise to misinformation around other topics.)

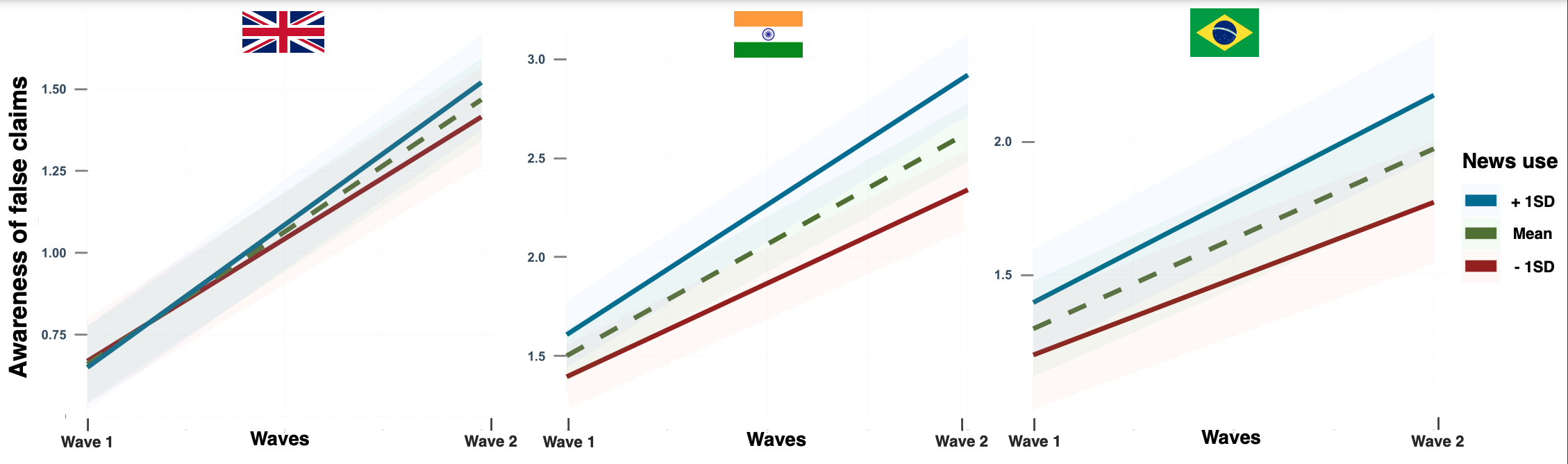

The figure below maps the evolution of awareness of false claims between wave 1 and wave 2 as a function of news use. Again, we asked about new false COVID-19 claims that emerged after wave 1, so we are interested in differences in the steepness of the lines and not in their direction. The green dotted lines represent the evolution of false claims awareness for participants with average news use, while the solid blue line for one standard deviation above the average news use, and the solid red line for participants with news use one standard deviation below the average news use. In India and the UK, more frequent news users gained a broader awareness of false COVID-19 claims between waves 1 and 2.

Finally, and arguably most importantly, belief in misinformation.

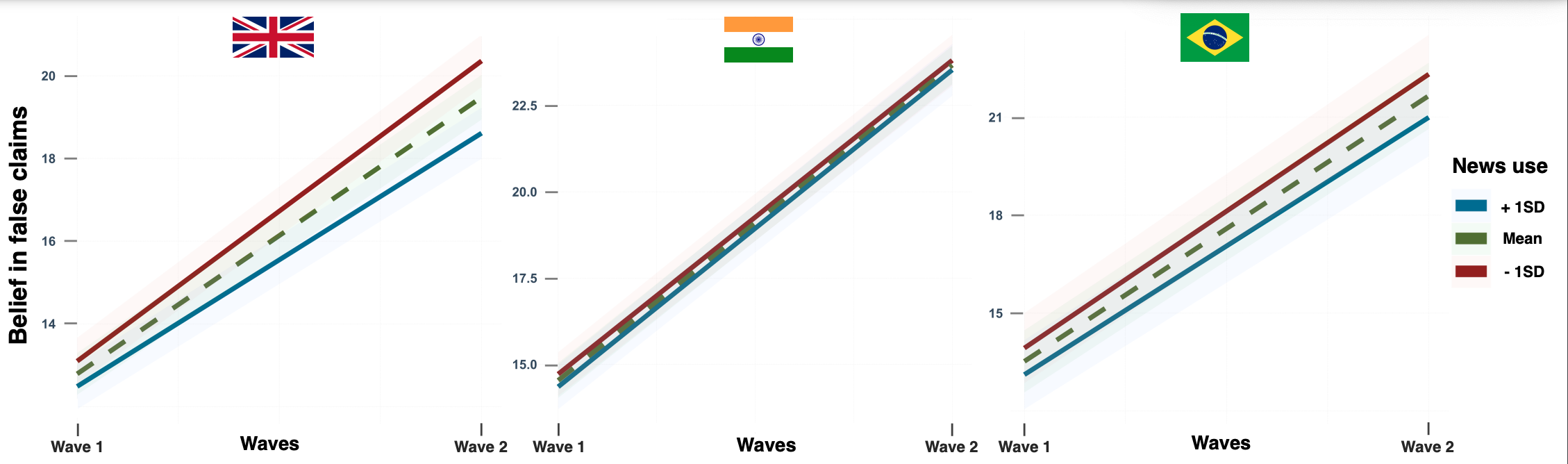

Exposure to misinformation has been shown to increase belief in false claims. Might news, as the researchers quoted at the outset fear, have the same effect? The figure below maps false belief acquisition between wave 1 and wave 2 as a function of news use. As before, the green dotted lines represent false beliefs acquisition for participants with average news use, while the solid blue line for one standard deviation above the average news use, and the solid red line for participants with news use one standard deviation below the average. In Brazil and India, more frequent news use had no statistically significant effect on false belief acquisition over time, and in the UK, more frequent news use actually weakened it.

The more detailed analysis in the working paper finds some differences across different categories of media and across online versus offline news use, but overall our analysis shows that:

- More frequent general news use led to stronger political knowledge gain over time in Brazil and the UK (in India, the results were not statistically significant)

- More frequent news use broadened awareness of false claims in India and the UK (the results were not significant in Brazil)

- More frequent news use did not increase strengthen false belief acquisition in any of the countries – and significantly weakened false belief acquisition in the UK.

News media continue to be important parts of many people’s media repertoires, and our main aim was to understand the impact of news use better. But people increasingly also (and in some cases instead) rely on various social media, messaging applications, and search engines.

Strong opinions about the implications of this abound in public debate, but empirical research has not yet produced a clear consensus on what relying on various digital platforms means for people’s political knowledge, awareness of misinformation, or belief in misinformation.

Overall, we find that more frequent platform use did not have a consistent effect either way. Because platforms, while having some common features, are even more different from one another in terms of how they are used, what they are used for, and what content they offer different people, we look at a range of platforms individually. The full regression models are in the working paper, and in most cases we find use of various platforms has no significant effects on political knowledge, awareness of misinformation, or belief in misinformation.

Our main focus in the analysis was news, but because misinformation is not exclusively about media or platforms, in all our statistical analysis we control for a range of other factors, including demographics, socio-economic status, political interest, trust in news, political orientation. The full models are in the working paper and I will highlight just one here – the relationship between political orientation and belief in misinformation.

We find some significant correlations here, but they are not the same across the three countries. For example, in the UK, participants who identified as left-wing were less likely to believe in false claims than participants at the centre of the political spectrum, while participants with no political affiliation (often people who feel disconnected from traditional forms of party politics) who were more likely to. In India, we found no significant effect of political orientation on belief in false claims. In Brazil, where some right-wing politicians have spread misinformation about COVID-19, participants who identified as right-wing were more likely to believe in false claims than participants at the centre of the political spectrum.

These results underline both that context matters (because they vary across countries) and that politics matters. Misinformation is about media and platforms, but it is not only about media and platforms.

In summary, our findings challenge the notion that news media in general, by drawing people’s attention to false and misleading content, leave the public more misinformed, and support the idea that news generally helps people become more informed and in some cases more resilient to misinformation.

The informational benefits of relying on various digital platforms – both when it comes to increasing political knowledge gain and weakening belief in misinformation – are much less clear. With a few exceptions, we find no significant effects either way.

Substantially, our findings raise questions for both platform companies and news media. Digital platforms may not feel it is their job to ensure the public is well informed, or at least not misinformed. But hundreds of millions of people across the world rely on them to access and find news and information and whatever the companies themselves think their role is, it is important to understand the effects they have on users.

If digital platforms would like to ensure that relying on their products and services leave people less likely to be misinformed, our work is yet another reminder that they clearly still have much work to do.

For news media, some of the findings are encouraging – relying on them often helps people become more knowledgeable about politics and, despite the concerns of some fact-checkers and researchers, while it does make people more aware of false and misleading claims, news generally does not leave people more misinformed.

So, in answer to the opening question, ‘can news help?’, our results are a clear ‘yes!’ and our research suggests it is important to complement efforts at fighting misinformation with efforts to get reliable news and information out as widely as possible.

News media can thus play an important role in helping people become more informed and more resilient to misinformation both by engaging in fact-checking and other practices that aim at identifying bullshit and debunking it and by staying true to their classic mission of seeking truth and reporting it to the whole public.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time