African journalists should join forces to expose white-collar criminals, says this pioneer of investigative journalism

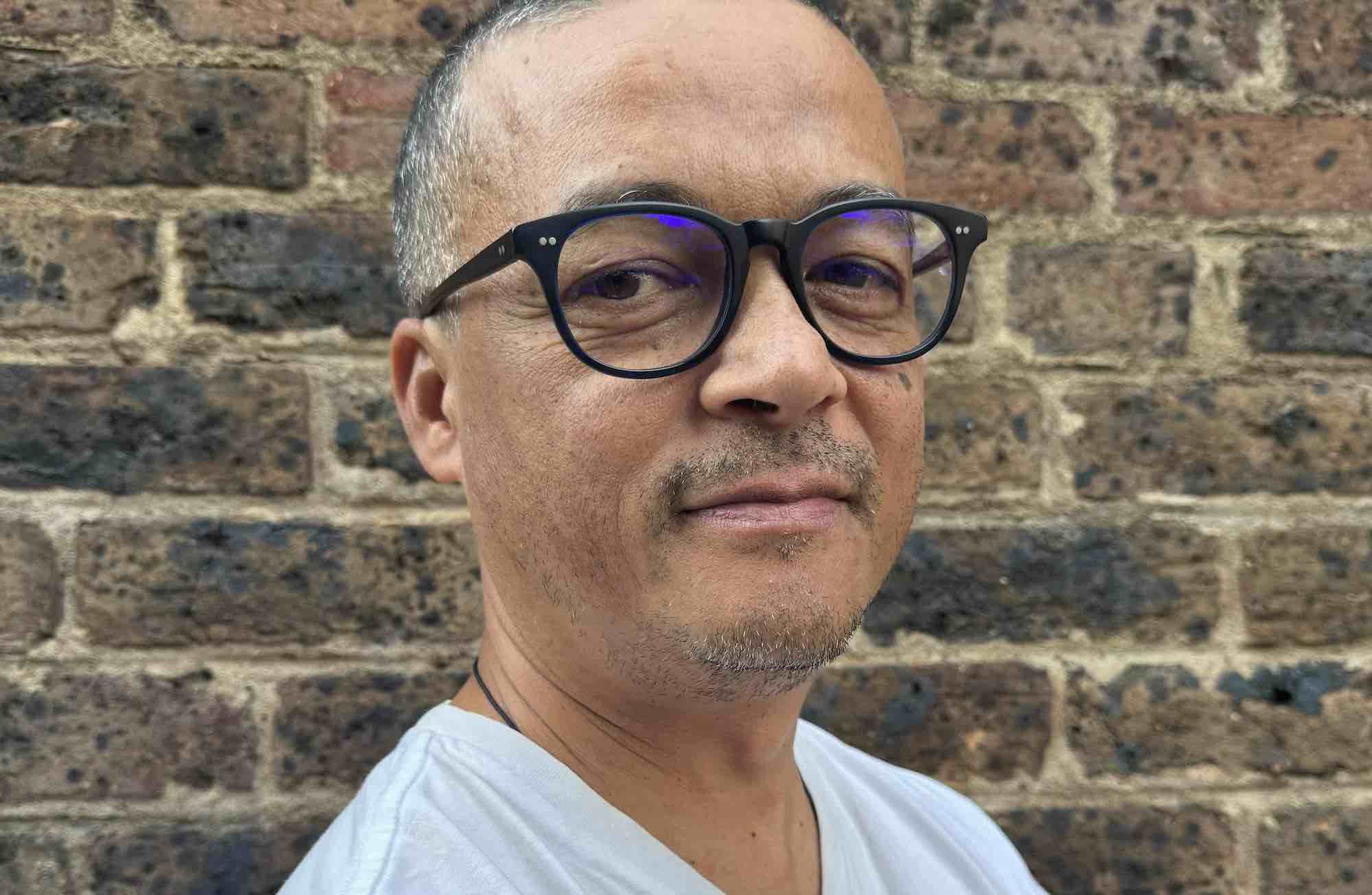

Investigative journalist Beauregard Tromp.

Beauregard Tromp is a veteran investigative journalist and the Africa editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), where he works with a team of editors and journalists to conduct cross-border investigations on the continent. Before joining the OCCRP, he was a Nieman Journalism Fellow, an editor at South Africa’s Mail & Guardian and senior reporter at The Sunday Times.

Tromp has travelled across the continent covering major events like civil wars and political unrest. He has won several awards. In this interview, he talks about his work, his views on investigative journalism in Africa and his plans as the new convener for the African Investigative Journalism Conference (AIJC), which will take place at Wits University in Johannesburg from 30 October to 1 November 2024.

Q. Can we have a sense of your work as the Africa editor at OCCRP?

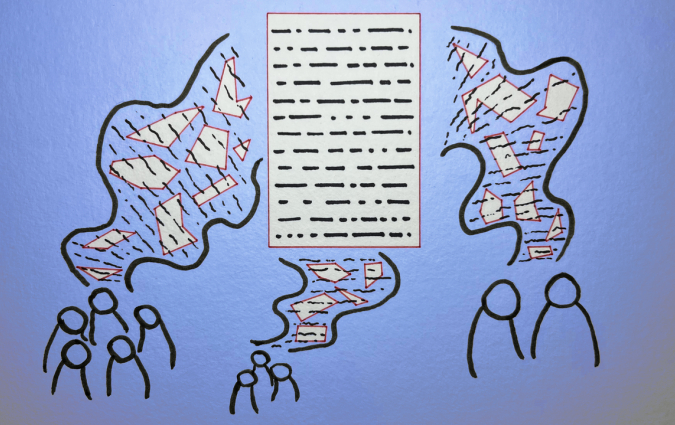

A. I manage a team of specialists across the continent. We have regional editors based in Dakar, Abuja and Nairobi, and our purpose is to identify opportunities for cross-border collaboration.

The reason this is coming to the fore more often is that we are finding that the groups that we are pursuing are increasingly no longer limiting themselves to the borders of a country. They work hand in glove with criminal and corrupt organisations to deal with the resources from one or more countries, and try to stash them away in places like Switzerland or the British Virgin Islands.

When you have that kind of infrastructure in place, it becomes incumbent upon us as investigative journalists to also create a similar structure to look to expose this and to combat this criminality.

Of course, we know that this kind of thing is way too rampant in Africa. It robs us off tens of billions of dollars in money that should go towards development. And we know who these people are. These are criminals in suits and some of them are politicians and even heads of state. We have to expose this.

Q. What else do you do at OCCRP?

A. We have certain research abilities which we look to share with other colleagues in order to empower them. We have a dedicated research desk and we have a specific person who deals with Africa. Similarly, we have a data desk and we also have a designated person to deal with Africa. The idea is to share all of those best practices which we see around the world to strengthen what exists already on our continent. We are looking for greater collaboration. We want to know where we can assist, where we can work hand in hand and create true partnerships.

When people speak about partnerships, it’s often some person sitting in the Northern hemisphere and saying this is what we are interested in. We African journalists were often used as golfers or fixers. We need to have real equality in terms of these partnerships. Otherwise, we cannot really call them partnerships.

As Africans, we must have a say in terms of what stories are critical to us. It can’t be simply you’re interested in the Sahel because Wagner is there. There must be a larger interest, which is driven from the people who live in those areas, who must set the agenda and say this is actually what’s critical for people in our region.

Q. I want to know your view on the state of investigative journalism in South Africa.

A. Investigative journalism has evolved considerably in South Africa in the past 20 years. You should keep in mind that South Africa is one of the youngest democracies on this continent. We’ve only had democracy for over 27 years, and the need for investigative journalism has picked up significantly in the last few years.

If we take the time to learn the lessons from post-colonial African countries, there's always predatory grouping to take advantage of what they see as opportunities to exploit any gaps that they might have for themselves. That's what we have seen in South Africa in the past 27 years, where increasingly we are seeing corruption creeping in. This is not to say there wasn’t rampant corruption under the Apartheid state. But now that you have a free press, corruption becomes more visible.

That is largely due to the work of investigative journalism. We had the State Capture very recently, which was the capture of certain key institutions of the state by criminals and criminal networks, including the Gupta family, who were working hand in glove with our former president, Jacob Zuma. And again, the exposing of that had started 10 years before by investigative outfits like AmaBhungane, who were then at the Mail & Guardian, and groups within the Sunday Times. Those are the two strongest investigative journalism networks.

Now we're seeing others from News24 and the Daily Maverick coming to the fore, and that is very encouraging.

Q. How do you think investigative journalism has evolved in the continent?

A. Countries like Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana have some of the strongest and most diverse media in Africa. You look at Nigeria, for instance, and they’ve got so many media outlets which are practising outstanding journalism and which are recognised by the public for doing more critical work.

I’m seeing something similar in Kenya, where the work of some institutions is really important. I remember being in Nairobi when Daniel Arap Moi relinquished power and it was a fairly tightly controlled media space. But in the aftermath of that, you are seeing more private media houses coming to the fore and a greater diversity of ownership.

You are seeing organisations like Africa Uncensored doing incredible, innovative work. You are seeing the work that Tiger Eye is doing in Ghana. They're doing incredible work, really world-class work. Those are the examples that I like to look at because there is not a one-size-fits-all way of setting up successful investigative outfits. You look at the homegrown organisations which have proved to be sustainable, like the two I've just mentioned, and those for me are the best examples of investigative outfits on this continent, along with AmaBhungane in South Africa.

Q. What are your plans for the African Investigative Journalism Conference?

A. I’ve been privileged to travel to nearly every country on our continent and I've met some incredible colleagues along the way and I'm still meeting new ones every year. In doing so, my role then is to tap into that network and say: “This person has great value to add.” So it's to bring those voices together to inform the conference.

That's the first part. The second part is working with a very strong existing group of core people who are involved in planning the conference, and this includes people from the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) and from the Wits Centre for Journalism. They know what they're doing better than I do. Most of them will be staying and will continue to help build the conference as we know it.

As far as moving forward, I don't believe that one should go and reinvent the wheel. A lot of what the conference has been doing over the past few years is incredible and we want to retain that. But I see opportunities for growth and for creating greater South-South cooperation. We should be dealing with our colleagues in South America, South Asia and other regions, and looking for areas of cooperation. It's fortunate that we have somebody like Emilia Díaz-Struck taking over at the GIJN almost at the same time as I am taking over.

It’s not just nice for us to meet people from other continents. We have to have something tangible. If there is one thing we learnt about journalism in the past 20 years, it’s the urgency for what we do. The urgency not only for the kind of work we do but also for the sustainability of the news business, which is constantly under threat.

Q. Which kind of feedback did you get from journalists?

A. We’ve heard people saying we need more sessions on funding. So one of the things that I would be keen to do is to actually make sure that we have sessions to take people through funding opportunities and business management skills training. People need that kind of training so that they can build something that’s gonna be there for many years.

The AIJC is a conference run by the Wits Centre for Journalism. So we will be working more closely with the team. We want to help inform how they train future generations of journalists so that those people are best prepared for the market essentially.

Finally, we are starting to realise this shouldn’t be just a one-off event. I would like to see us more active throughout the year. I’m not talking about workshops and the like. You need to actually be completely immersed in something to pick up that skill. This is the kind of thing we are looking at doing in the future.

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time