In this piece

A harm-reduction playbook for covering populists

Michael Hauser Tov, chief political correspondent at Haaretz, sets out a research-backed harm-reduction playbook for our addiction to covering populist politicians. Credit: DALL·E

In this piece

First, name the problem | Quick ID: when to switch to harm-reduction coverage | Why the usual options backfire | The techniques (you can use them tomorrow) | Three common dilemmas, answered fast | But what about objectivity?It’s a dark season for politics – and for journalism. Populist politicians are rewriting the rules, and we keep giving them oxygen. There are plenty of explanations for why they get so much coverage – most obviously, it drives engagement – but at this stage the why isn’t the point. When a doctor finds metastases, they don’t ask why the patient started smoking. They decide what to do next.

If we treat our coverage like an addiction, the solution becomes obvious: harm reduction.

A decade ago, TripSit’s volunteers published a chart showing which drug combinations are low-risk and which are dangerous. They weren’t promoting drug use; they were accepting reality and limiting the damage. Journalism now needs the same kind of framework.

During my Reuters Institute fellowship I built a playbook that adapts harm-reduction to political coverage. The goal isn’t to eradicate coverage – that’s impossible – but to reduce the harm it can do to democratic discourse and to journalism itself. This is the short version. You can download the full, printable toolkit (matrix + checklist + FAQs) at the end.

First, name the problem

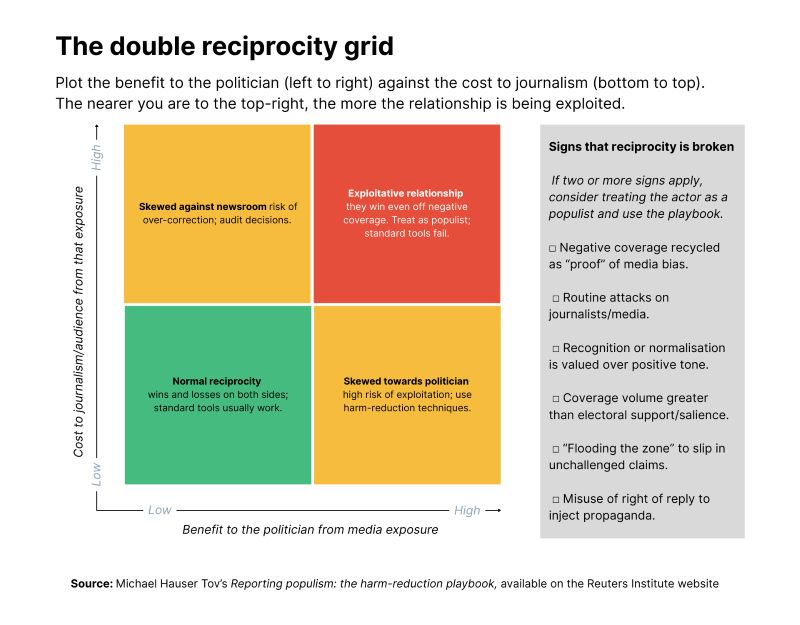

Populism isn’t just a style. As expert Cas Mudde argues, it’s a thin ideology that splits society into “the real people” and “the corrupt elite”. That framing is step one. Step two is what researchers call the double reciprocity break. In a healthy journalist–politician relationship, both sides win and lose over time. Populists game that relationship so they win whatever the tone – even when coverage is negative. That’s why standard tools keep failing.

Across countries, studies have found that lower or even critical exposure didn’t halt the spread of populism. Status beats tone. Anti-media attacks recycle our criticism as “proof” of bias. As Kalyani Chadha puts it: if we want different results, we have to abandon standard practice.

Quick ID: when to switch to harm-reduction coverage

Treat a figure as “populist” for coverage purposes if both are true:

- People vs “corrupt elite” framing in their rhetoric; and

- Broken reciprocity with the media – criticism fuels them; recognition/normalisation matters more than tone; routine attacks on journalists.

Signs reciprocity is broken? Tick at least two: negative coverage recycled as proof of bias; “flooding the zone” with claims; coverage volume exceeds electoral support/salience; misuse of the right of reply.

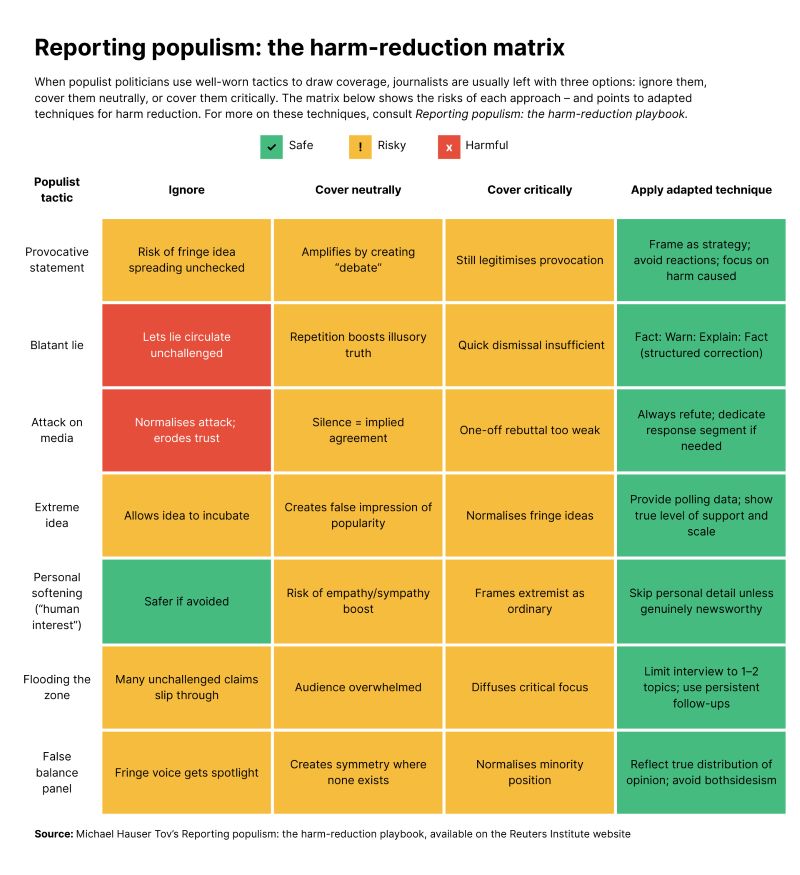

Why the usual options backfire

In the moment, most of us default to one of three: ignore, cover neutrally, cover critically. Each carries predictable risk:

- Ignore – the claim spreads unchecked somewhere else.

- Cover neutrally – you create a phoney “debate” and confer status.

- Cover critically – you still confer status and feed the “media hates us” script.

The fix is not less coverage; it’s different coverage.

The techniques (you can use them tomorrow)

- Prebunk before live. Warn audiences what’s likely to come and remind them of earlier lies. Inoculation beats clean-up.

- Don’t headline the reaction. Describe the statement, not the outrage it triggered, or you turn a stunt into “legitimate debate”. Focus on impact and who’s harmed.

- Correct lies with F-W-E-F. State the Fact. Warn the audience they’re about to hear a lie. Explain how the lie misleads. Restate the Fact – more than once, if possible, to blunt the “illusory truth” effect.

- Avoid false balance. If you platform two sides, show the real distribution of expertise or public support (e.g., “60 economists against, one for”).

- Show true support for ideas. When airing extreme proposals, add polling on the specific idea so coverage doesn’t inflate perceived popularity.

- Show the true scale of events. Replace “political firestorm” with numbers (“five MPs criticised”). Quantify; don’t dramatise.

- Name the behaviour, not the category. Skip the softened catch-all language (“populist”). Say what they did: spread a conspiracy theory; made racist statements; incited harassment.

- Keep interviews tight. One or two topics, persistent follow-ups. Don’t let them “flood the zone” by smuggling unchallenged claims into the segment.

- Protect the right of reply. Cut irrelevant attacks and falsehoods from their reply; add your correction. Right of reply isn’t a licence for propaganda.

- Respond to anti-journalistic attacks. Silence reads as agreement, not objectivity. Build short segments that dismantle the claim against your newsroom.

- Skip soft-focus lifestyle unless truly newsworthy. Humanising detail boosts receptiveness to the message.

- Collaborate. Your restraint fails if your competitors platform the stunt. Agree boundaries (live carriage, debate criteria), share polling, and sometimes act in concert – we have precedents that show this works.

Three common dilemmas, answered fast

When should we ignore a claim? Ignore if it hasn’t crossed the “tipping point” beyond its originating audience; otherwise coverage will be the amplifier. Placement matters too – keep fringe items off front pages and leads.

How should we cover provocations? Frame as strategy, not spectacle. Report the statement itself, its aims and effects (especially on ordinary people), and avoid reaction headlines and superlatives.

What’s the best way to correct a lie on air? Use F-W-E-F. Correct every repetition to blunt familiarity-as-credibility. And when you can, don’t platform the lie in the first place.

But what about objectivity?

This isn’t about abandoning objectivity; it’s about reinterpreting it. Objectivity is a tool, not the goal. As Jay Rosen argues, the challenge isn’t “how to cover X” but how to restore conditions where our work matters.

Be objective in method; don’t normalise in effect. Or as Margaret Sullivan told me: we’re in a different era; playing by yesterday’s rules helps the people rewriting them. Using one technique with populist politicians and not with another may not be the most objective act, but it is a journalistic act. In fact, it aligns with other journalistic values that are no less important – foremost among them: providing the audience with the truth, and only the truth.

When covering populist politicians, we journalists need to work with a different set of guidelines.

The techniques in the playbook don’t cost money, needn’t hurt ratings, and don’t undermine journalistic principles. They simply require thought, which every journalist has a duty to invest.

The playbook above draws heavily on the guidance and work of Dr. Ayala Panievsky. Her new book, The New Censorship: How The War on Media is Taking Us Down, served as both inspiration and a key source for much of the information presented here.