In this piece

The decline and dispersal of Roma representation in Hungarian media

The author, Zsofia, pictured here with journalist fellows at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (Picture: John Cairns)

In this piece

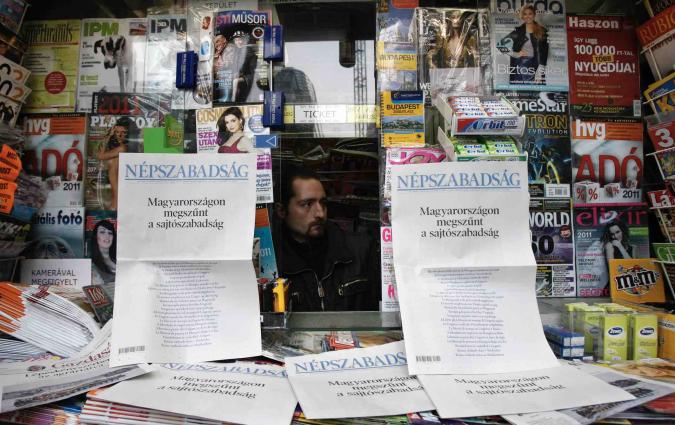

Lesson 1: Ditch the mass appeal and focus on core audience | Lesson 2: A feasible business model includes multiple platforms | Lesson 3: Young people need the return of entry-level opportunities | Challenges and opportunitiesMedia coverage holds significant influence over the social, political, and economic opportunities available to historically marginalized minority groups. In the context of Hungarian media – with its decreasing press freedom, increasing political influence and the concentration of media ownership – it’s hardly surprising that advancements to better representation of the Roma community have stalled.

“There are hardly any minority-owned media left, and barely any Roma journalists in the mainstream media,” Róbert Báthory, a Roma journalist working in Hungarian mainstream media told me. “This is a lost cause.”

Roma-owned media outlets that once thrived, such as Radio C, Dikh TV, and the Roma Press Center, have experienced challenges like funding struggles, digital disruption, and side-lining of serious content in favour of “cultural fluff”.

“It has never been beneficial to politics for the Roma people to become self-aware. Politics always fears an ethnic group who is not afraid of speaking up,” said Dikh TV founder, Elek Balogh. “Our channel was [becoming] a platform to shape opinions.”

But all three outlets also offer key lessons for those looking to take advantage of opportunities for a new wave of digital-first Roma media initiatives. To capture these, I interviewed journalists, editors, and media researchers, both Roma and non-Roma. They highlighted nine challenges and opportunities for Roma voices (see full PDF below). Here, I highlight three key lessons.

Lesson 1: Ditch the mass appeal and focus on core audience

Social media holds promise for Roma representation but it is currently disorganised and cacophonous. Mainstream media can only provide Roma communities with access to a variety of generalised public service information about society at large. But minority-owned media, operating successfully across multiple social media platforms, has the potential to change everything.

As Roma media researchers Vera Messing and Gábor Bernáth explained: “Minority media is one of the most important tools for maintaining the identity patterns of the given minority, it is a place for internal self-organisation, and for internal control of minority politics.”

Other roles of minority-owned media include:

- Reaching the minority with information which the majority media doesn’t provide them;

- Uniting the Roma community;

- Having an advocacy role as pressure tool to influence policy;

- Being the voice of the otherwise voiceless;

- Highlighting the potential and the positive developments of the community.

Notice that the list does not include challenging the majority outlook or stereotypes. In a controlled public sphere, the government is the primary actor that decides what gets on the public agenda. It’s difficult for independent voices to challenge the narrative, let alone independent minority voices.

As Dikh TV’s Balogh told me, a good minority media outlet can operate as a bridge between the Roma community and the rest of the society to better understand each other. But this should not be a primary aim of minority-owned outlets. To succeed in 2024 and beyond, they will need to meet the needs of a clearly defined audience – not dilute the message for mass appeal.

Lesson 2: A feasible business model includes multiple platforms

Paying for news, especially online news, isn’t the cultural norm among the Hungarian audience, but subscription and reader revenue models have started to grow. There is evidence in other markets to suggest that, with the help of seed grants, innovative minority-owned outlets with robust editorial plans that encompass multiple formats (newsletter, audio, vertical video, and events) and offer the Roma audience unique utility may succeed.

“If the minority media can get away from trying to influence the majority media and its depiction of the Roma community, they can work just fine,” said Bernáth. “That’s how Radio C [the most popular Roma radio station] worked and that’s how I think a prosperous minority media outlet would work today. I must admit, they saw the future better than us. I would do something like Radio C today.”

Lesson 3: Young people need the return of entry-level opportunities

“I always say that I am Lajos Orsós: a journalist, a communication expert and (by the way), Roma,” a veteran Roma journalist told me. But while personal intention and diligence are important, he said the Roma youth also needs opportunities. That’s what he got, and that’s what is missing today.

Orsós was 18 years old when he saw a call for young Roma who were interested in working in the media and learning English. He applied and was chosen from among a thousand applicants for the RTL Klub internship. After a year of training he was offered a job as a news producer, so he decided to stay. He was with RTL Klub for 18 years before leaving. “I lived my first 18 years in one of the most underdeveloped regions of Hungary, in a slum, in extreme poverty. And suddenly I found myself in Budapest, working for one of the biggest commercial TV channels. I am lucky.”

Fellow Roma journalist Róbert Báthory agrees: “Ten to 15 years ago, it was way easier to get into the media as a young and aspiring Roma journalist. There were several internships which have slowly died off, today there’s no resupply.” Now, he said, potential young Roma journalists are more likely to take a position at a big Roma NGO – that’s if they don’t emigrate to Western Europe or the U.S. first.

Challenges and opportunities

At a time when so much attention is being paid to the struggles of the mainstream media in Hungary, I wanted my journalism fellowship project to record the challenges and opportunities of minority journalists in this context.

To do so, I looked first at historical context, summarised the challenges of the current market, and sought to identify lessons from Roma media voices – both in the mainstream and independently owned – by interviewing both Roma and non-Roma media researchers and practitioners. (Find the full PDF below.)

It’s alarming that a once-vibrant market of Roma-led independent outlets has all but vanished over the past 20 years. Yet, there are lessons what we can learn from them that may serve as guardrails for the future.

Although it helps, money alone will not solve these problems: creative ideas, multi-platform experiments, and hardworking people are also needed.

In the end, one request remains to be communicated from the Roma community to media in Hungary. It is one repeated by minority groups around the globe: “Nothing about us without us.”

This project and fellowship have been made possible by the support of the Thomson Reuters Foundation.