In this piece

Climate technology reporting: without context and perspective we mislead our audiences

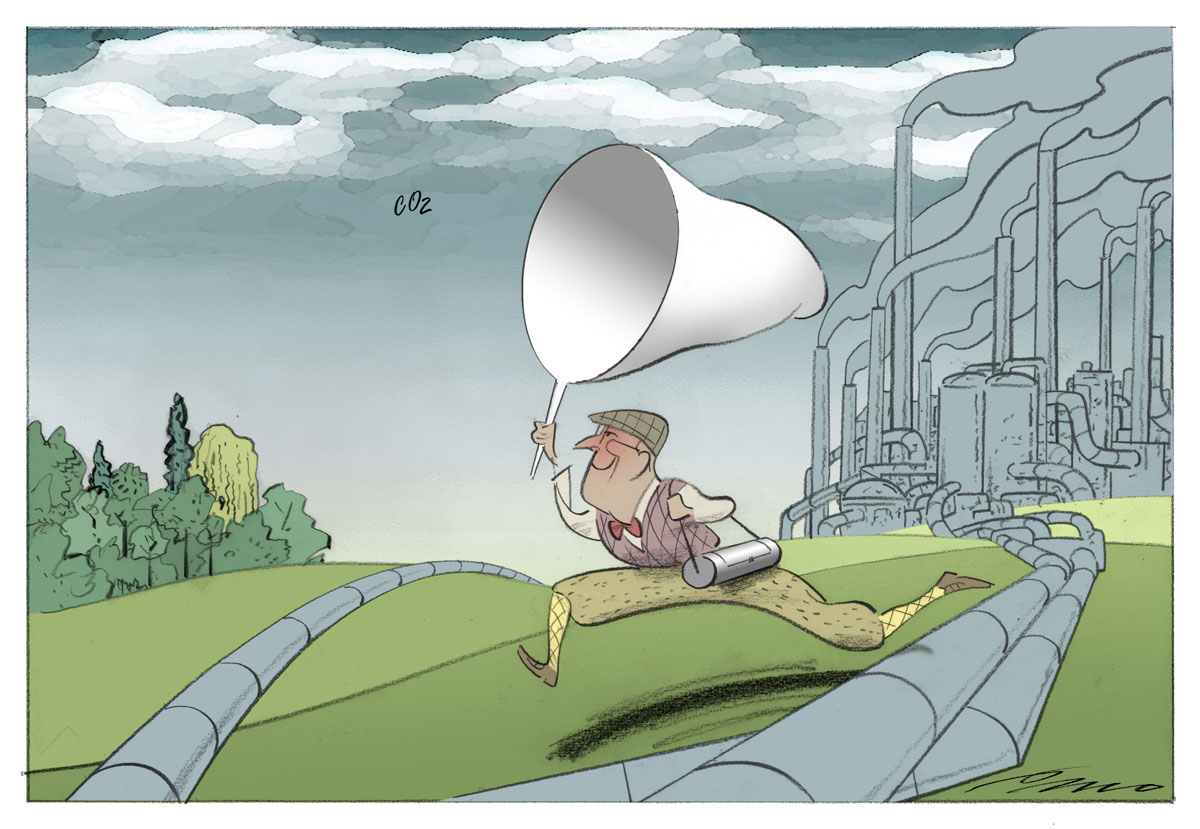

A cartoon by Per Marquard Otzen illustrating carbon capture and storage, first published in Politiken on March 12, 2023. Credit: Per Marquard Otzen/Politiken

In this piece

Overly positive narrative | ‘Technological fix discourse’ | Industry bias | The climate tech news cycle | RecommendationsCarbon capture and storage (CCS), green hydrogen, sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) promising green flights, and biochar produced with pyrolysis. These are some of the new climate technologies that most governments rely heavily on to meet their climate targets.

New climate technologies comprise a large share of news media’s climate coverage, but newsrooms generally fail to relate the potential of new climate tech to the urgency of the climate crisis.

This is one of the conclusions of my fellowship project, which polled 50 climate journalists from Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. I also conducted long-form interviews with six experienced Scandinavian climate journalists and three scholars specialising in climate journalism.

Overly positive narrative

In the poll, 69% of respondents labelled climate tech coverage as either optimistic or positive, with only 20% finding it neutral.

“We tend to write about the technologies completely out of context and proportion. By doing so, we fool our readers,” said Alexandra Urisman, an award-winning Swedish newspaper reporter.

Global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, and the scientific projections for temperature rise and heatwaves, droughts, flooding, and sea level rises become ever bleaker.

“When you look at the numbers for how much carbon CCS will store, it’s basically nothing. And still CCS is used in every single political statement around the world as if it is going to save us all,” observed Urisman.

Reporter Daniel Värjö from public Swedish radio noted that most politicians refrain from talking about the fundamental changes needed to mitigate and adapt to the climate crisis.

“Sometimes you get the picture that CCS will solve everything. But it is a false hope,” he said. “In general, we are failing. We have to be critical and investigate those [climate tech] stories”.

According to the poll, technology stories account for between 10 and 25 percent of climate coverage in half of the Scandinavian media outlets and more than 25 percent in more than a third of the outlets.

Kristian Elster of Norway’s public broadcaster sarcastically remarked: “I usually call [these stories]: Norway saves the world chapter 4,224. At article number 394, I thought I had done enough”.

According to Elster, it is difficult to determine if journalistic standards are compromised in individual climate tech stories. “But the volume of them may very well create a false, unfortunate impression”, he said.

‘Technological fix discourse’

Associate Professor Mikkel Fugl Eskjær from Aalborg University, Denmark, believes climate reporting has a “technological fix discourse”. “It is this constant optimistic idea that we can modernise ourselves out of the climate issue, that we will find the technologies which allow us to continue our lifestyle, and that they will be climate-friendly,” he explained.

While media reporting does become critical when a specific technology fails to fulfil the promises, coverage of other technologies continues in the same optimistic vein.

“It’s totally fragmented and not related to the technology that fails in the end,” Fugl Eskjær stressed.

In many newsrooms, there is a push for stories of hope as the climate crisis worsens, enforced by a strong focus on Solutions Journalism.

“The editors always want a hopeful point or to report about solutions,“ remarked Swedish radio reporter Värjö.

Professor Andreas Ytterstad from Oslo Metropolitan University said: “It’s interesting to note that when climate journalism tries to be positive, it very often means being technology positive.”

Industry bias

My poll of Scandinavian climate journalists revealed that individual companies and industrial associations initiate most climate tech stories.

When filing their stories, reporters often quote scholars, but many struggle to find non-biased experts sources.

Most scholars are deeply involved with the deployment of new technologies, as academic funding is distributed to projects in co-production with industry and government agencies. “It can make it hard to find scholars […] who are not wedded to a particular project utilising that technology,” said Professor Ytterstad.

Huge government subsidies to climate technology further incentivises newsrooms to increase tech coverage.

The consequence is a skewed public focus diminishing the impetus for urgent behavioural climate action, deplored by climate reporters and scholars alike.

“If politics and media functioned optimally, we would be discussing how to spend taxpayers’ money to reduce emissions as much as possible. Yet, we don’t cover a solution like behavioural change”, said Mads Nyvold, editor of Danish niche media Klimamonitor.

Academic studies have repeatedly identified a large industry bias and positive narrative in climate tech coverage, leading to scholars warning of policy implications in peer-reviewed literature.

The climate tech news cycle

In my project, I argue that climate tech coverage is trapped in a cycle. It starts with a population unwilling to lower consumption and thereby emissions, often equating it to a loss of welfare. Despite the reticence to act, there is still a public push for climate action.

This makes governments turn to tech, funnelling huge subsidies to industries, and grants to academia. Industry and academia have professionalised how to sell the stories of climate tech benefits to newsrooms.

Tech stories may seem like an easy answer to the push for a hopeful climate narrative in many newsrooms, offering audiences a way out of the climate crisis without lowering consumption – leaving us back at the starting point of the cycle.

Recommendations

Most of my recommendations to break the climate tech news cycle can be implemented even in small newsrooms:

- Add perspective and context to technology stories by providing the best possible estimate of potential for emission reductions and comparing to the reductions needed to meet, for example, the Paris Accord.

- Evaluate the climate tech coverage to ensure a balanced narrative and use of sources.

- Set up structures to bring the experienced climate reporters into play. Many tech stories are filed by general assignment reporters.

- Hold expert sources to account for their conflicts of interest. This basic skill is too often skipped in tech reporting.

While my project only polled and interviewed Scandinavian climate reporters, many of the dynamics of the climate tech news cycle exist in other countries, particularly in Northwestern Europe. Thus, these recommendations may also prove helpful outside of the Nordics.

For the full results of Magnus Bredsdorff’s fellowship, download the PDF below.