In this piece

What should a 'Modern Reporter's Notebook' include in the 21st century?

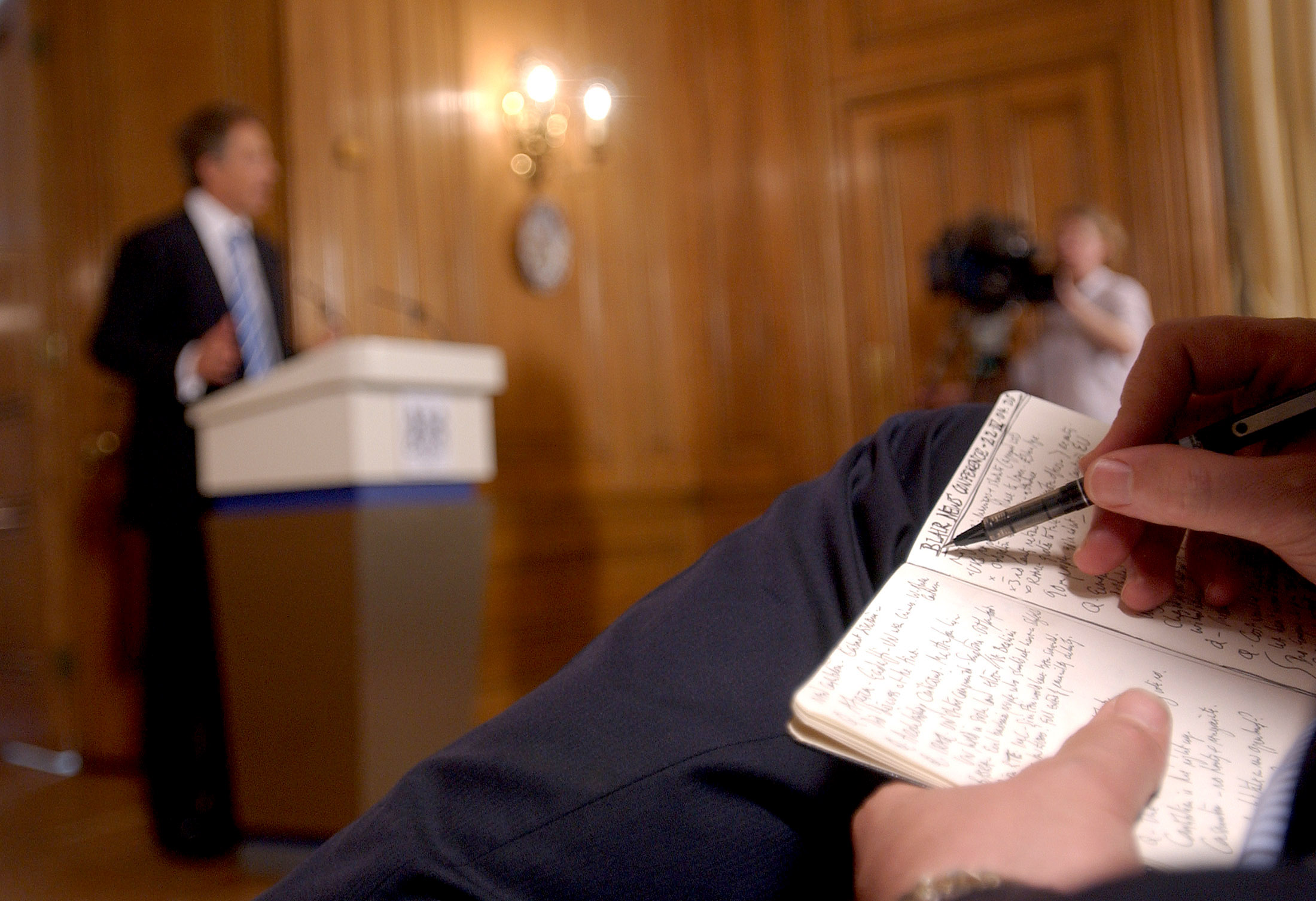

What features should a reporter's notebook contain in the 21st century? REUTERS/David Bebber

In this piece

What are most of us using? | So what's stopping us from trying something new? | Where could more experimentation take us? | The case for changeWhat would happen if journalists thought more comprehensively about how technology might aid their professional practice — especially around reporting — and worked to actively experiment and incorporate what works into their professional practice?

This was the focus of my work at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, where I reviewed literature and conducted interviews with 12 reporters from seven countries about the tools they currently use in their reporting practice and what stands in the way of incorporating new tools into their standard kit.

My hypothesis is that the reporting function of journalism – unlike the production and distribution functions – is not making the most of the opportunities technology presents. By being more open to using new tools we could super-charge our ability to "collect, store, retrieve, analyse, reduce and communicate" — key functions of the journalistic practice.

As my research and interviews progressed it became clear that reporters are not eager early adopters of new technology but often make do with what they're familiar with or have easy access to. Usually that means settling for something that is not made with journalism in mind. But an emerging appetite for new ideas also revealed itself, with some reporters expressing a dawning realisation that they should be experimenting with technology more and a minority having already travelled a long way down that road.

What are most of us using?

The world of journalism is overflowing with lists of tools: for research, open source investigations, verification, monitoring tools for social media, or the movement of people and goods… the list goes on.

Yet at the same time, there is a clear reluctance to try new things, to experiment with technology. Considering the wide variety of countries, cultures, reporting beats and publication types represented, the reporters I interviewed had a surprisingly homogenous set of tools. Google Docs, email and Google Search are their most commonly used bits of tech.

I was particularly interested in the use of Google Docs as our go-to digital equivalent to a physical reporter's notebook because I'm both convinced we can do better and suspect we're not making the most of what it can do.

So what's stopping us from trying something new?

There is so much change that we must undertake as journalists – new content management systems, formats and communications tools – that to deliberately go in search of more new ways of working may seem overwhelming or absurd. This is to say nothing of the challenges that smaller budgets and a diminishing workforce place on journalists.

Many feel the tools they do have, though not perfectly fit for purpose, are “good enough”. Without a very compelling reason, time-poor journalists will “make do”, so there is no need to change. This could be mistaken for resilience, but it’s costing individuals, newsrooms and our audiences.

In a wonderful essay about journalism's relationship to technology, Barbie Zelizer theorised: “It is often said that journalists are resistant to change, but perhaps what they resist more is the diminution of their craft that often comes with it.”

There is some truth to that, but another plausible explanation is that journalists are conditioned to accept the status quo and not trained or encouraged in the application of new tools to our craft. Unlike in the wider technology industry, there is no prominent journalism culture for experimenting and seeking new tools.

While other factors should not be dismissed – money and time most notably – I think this cultural element is the key factor holding reporters back from experimenting. Too often we are passive receivers of technology, waiting for the next thing to be imposed upon our practice, rather than actively pursuing how we can harness technology for the betterment of journalism.

Where could more experimentation take us?

One place I would encourage reporters to start experimenting is in the software they use for notetaking. There are quite a few tools in the ‘personal knowledge management’ category that are worth trying, including Roam Research, Obsidian, Athens, Evernote, Notion, Nette, Scrivener, Bear, Tiddlywiki, Simplenote, and Muse.

Two journalists I interviewed have been using tools in this list – Evernote and Notion – for their reporting. Although these are not purpose built with journalism in mind, they provide demonstrated utility for reporting beyond what generic word processing packages like Google Docs can.

Persist with a tool like this long enough, and embed it as part of your standard workflow, and it becomes a kind of personal Wikipedia – an interlinked and well-organised repository of knowledge that’s searchable. That kind of knowledge bank can become “invaluable”, as one reporter put it.

And I think we can go even further: we could harness technology in ways that will not only improve our reporting but allow us to find and tell stories that would never have been found otherwise. This is where the idea of an application programming interface (API) for your note taking software opens up some exciting possibilities. An API, in this context, is a set of functions offered by a piece of software that would enable third party developers to extend the software’s core functionality.

With the right software and API, a journalist's notes could be connected with, for example, systems that support highlighting and annotating PDFs or other documents in a document library, so the most important reference material all lives in one place and links to originals are automatically created.

Or functionality might be added to define and detect entities like people, places, organisations, dates in a way that makes it possible to chart networks and identify patterns. Again, there are tools that already exist that provide capabilities like this – Maltego is a notable example – the right API would allow a reporter’s notebook itself to be extended with these capabilities.

I imagine these and other possibilities in my paper, which can be downloaded below.

The case for change

Journalists use computers and software in their processes, yes, but the tools they use most were designed for other purposes. It is largely coincidental that their utility is general enough to make them useful for journalistic processes. So the question remains: what are reporters missing out on by settling for general-purpose tools like word processing software for research, note taking and drafting?

The fact that most journalists I spoke to rely on relatively simple tools that are not purpose-designed lends credibility to the idea that there is space for more fit-for-purpose tools.

During my interviews with journalists, many of them expressed a dawning realisation that there could be a better way. “Having this conversation makes me think maybe I should stop thinking in the old school way,” said Maurice, an investigative documentary filmmaker from Kenya.

Technology companies looking to support journalism through the development of products have the potential to offer journalism something of enormous value in the reporting space. However, they should take the time to better understand the processes and functions of journalism, and the difficulties new products in this space face around adoption.

Newsrooms need to have a strategy for empowering and encouraging journalists to seek and employ new tools in the reporting process. Newsroom managers should consider the question: what organisational resistance would a reporter in this newsroom meet if they wanted to install or trial a new piece of software on their work computer?

The challenge will be in overcoming impediments to adoption and demonstrating enough short-term value that reporters persist with using them over the long term.

In an ideal world, what kinds of functionality would you want a digital reporter's notebook to have? What other techniques and technologies have made your reporting better? No, really, tell me — I'd love to know what you think.