In this piece

Journalism in Argentina is in crisis. Lessons from Spain and France may hold the key to survival

A magazine with the image of former Argentine President Mauricio Macri is seen at a newspaper stand in Buenos Aires, Argentina in August 2019. / REUTERS/Agustin Marcarian

In this piece

Searching for a different direction | 1. A similar diagnosis. | 2. Membership or subscription? That is the question. | 3. Journalist ownership but a professional approach. | 4. Innovators andleft-wingleaders in the middle of information overload. | 5. Media discourse, transparency and participation. | How to apply these lessons to ArgentinaIt is not journalism that is in crisis but the business model that has supported it for decades. This is clear from what happened in Argentina on 24 April 2016. On that day Tiempo Argentino printed its first edition as a cooperative newspaper. It sold out, shifting its 30,000 copies in four hours as a cooperative. Its circulation was now 10 times bigger than it had been just 80 days earlier, when it was owned by a more conventional businessman. This owner saw newspaper ownership as a route to profit. When its profitability came under threat, he first stopped paying journalist wages and then stopped printing the paper.

It seemed the end of the newspaper but in fact it was the start of something more significant.

The day the owner announced he was closing the newspaper, the employees decided to occupy the editorial offices. We decided we wouldn't move from there until the owner paid us compensation. We threw down mattresses between computers and started a stay which would last ten months.

We put together music festivals to raise money and marches to make people aware of what was happening. We used social networks to share our struggle and also to publish news articles about what was happening in the country. Without the constraints of the old owner and basically without a newspaper, we had more readers than before.

This is why we decided to publish a special supplement on 24 March, the date that marked the 40th anniversary of the last coup d’état.in Argentina. We wanted to meet with the readers and find out whether they were interested in supporting a collective news operation. That day we sold out all of our supplements and returned to the newsroom to hundreds of emails and a renewed energy.

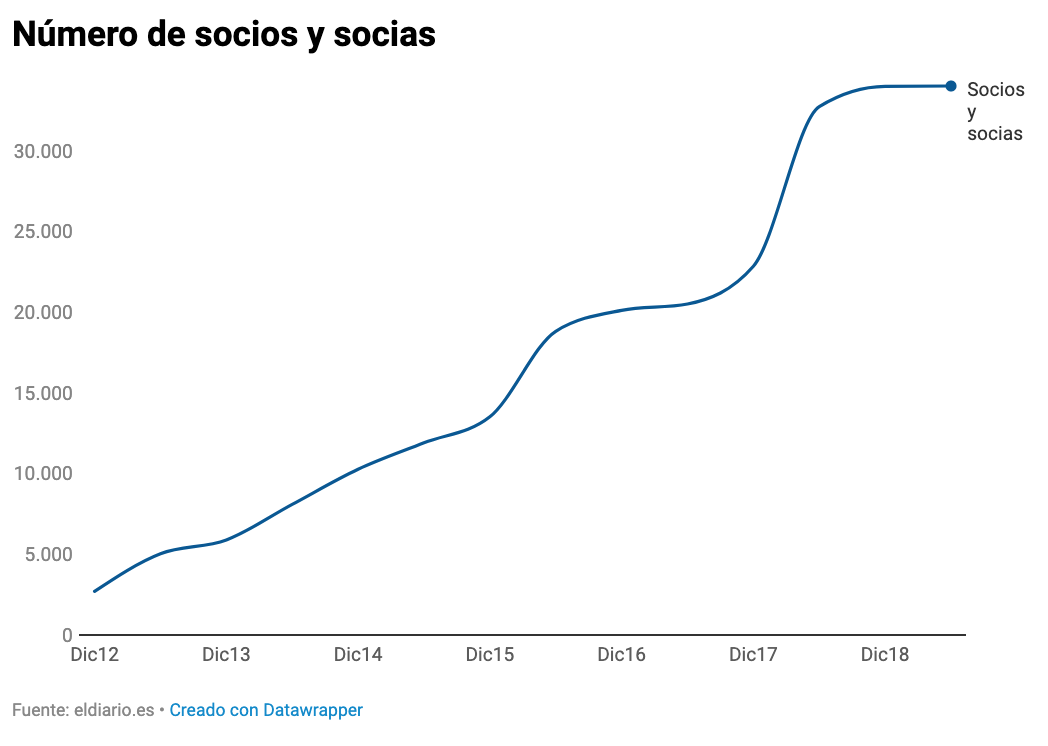

We decided to form a non-profit organisation where all of the members are involved in decision-making and we took a chance on reader revenue. We were unwittingly developing the first membership model in Argentina. For this reason we were inspired by what other news sites were doing, particularly eldiario.es in Spain. We studied it and adapted our proposal.

This is how Tiempo Argentino was born. It's a digital newspaper with a printed edition on Sundays (the day on which newspaper sales are tripled). Ours is a form of subscription where you receive a printed edition at home. Members pay an additional fee to support the construction of an independent project and to ensure that even more readers can access free content. We are about solidarity. People pay not for exclusive information but so that more people can read us.

In three years Tiempo managed to maintain 100 jobs whilst traditional news outlets fired about 3,000 journalists in Buenos Aires. This miracle happened thanks to the support of our readers. Their memberships represented 70% of our income.

Searching for a different direction

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Nicola Bruno wrote that “survival is a success” for new media. For Tiempo this feeling of fragility seemed much greater. We had no financial backing and we relied on reinvesting our income. To top it all the economic crisis worsened and the media industry came under renewed pressures everywhere.

As chairman of the cooperative, I asked myself several questions. How many readers are willing to pay for information in this time of media saturation and distrust? How many business models are there relying on reader revenue? What can we learn from experiences in other regions?

These questions encouraged me to apply to the Journalist Fellowship at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. For six months, I studied several projects and decided to focus on two of them which seemed the most interesting to me due to their growth and incidence: eldiario.es in Spain and Mediapart in France.

Both were funded by experienced, respected journalists who sought to keep control of the editorial line and share ownership. Despite their relative newness, they are very well trusted by their readers. Here are some of their main characteristics.

I asked questions and read about them but I needed more. For this reason I spent some time in their editorial offices. I saw how they worked and interviewed them. Finally I spoke with the founders of other news sites that emerged in the same context and attempted to gather reader support but still haven’t achieved the same impact. So I summed up the experiences of Infolibre, La Marea and Ctxt in Spain; and of Rue89 and Les Jours in France.

I tried to summarise this work-based learning which arose when finishing my fellowship. My paper is now published. It explains the editorial offices and the reasons that motivated them for each decision they made. It also analyses the differences and the examples of how their different business models operate. Here I have summarised my main findings.

1. A similar diagnosis.

Both eldiario.es and Mediapart emerged during a crisis of institutional representation. This mistrust affected both political and judicial power as well as mass media, which were majority-owned by large corporations that appeared to have a conflict of interest with the editorial line. Supporting eldiario.es or Mediapart would also defend democratic values.

“The key is that the business model shields the editorial model,” Escolar told me in one of the research interviews. “If eldiario.es was born backed by an investment fund or a larger communication group, then we wouldn’t have had to do what we did."

Mediapart summarized this approach in its slogan: “Only our readers can buy us.” And created a model without advertising sustained 100% by subscriptions. Edwy Plenel, its editor, summarised its design as follows: “We are valuable because of the information we provide. Readers help us to exist because, without us, there would be a lot of things they wouldn’t know.”

2. Membership or subscription? That is the question.

As seen clearly in the words of Plenel, the Mediapart proposal was transactional from the outset. If someone wants to read, they must pay. But at the same time, themodel included promotions and alternative access points so the paywall did not stop anyone from getting to know a new media. “We believe that people first visit to investigate and then stay for the rest of the content,” said Marie-Helene Smiejan, co-founder and financial manager.

Time proved her right. Shortly after, Rue89 was born. It was inspired by Korean OhMyNews. It promoted grassroots journalism and mixed professional journalist articles with bloggers on their front page. They took a chance on traffic and their success was as quick as it was short-lived. They were the first digital-born site reaching one million users solely in France. But the internet bubble explosion forced them to sell the company four years after its foundation. Today they rely on Le Monde with a team of four people.

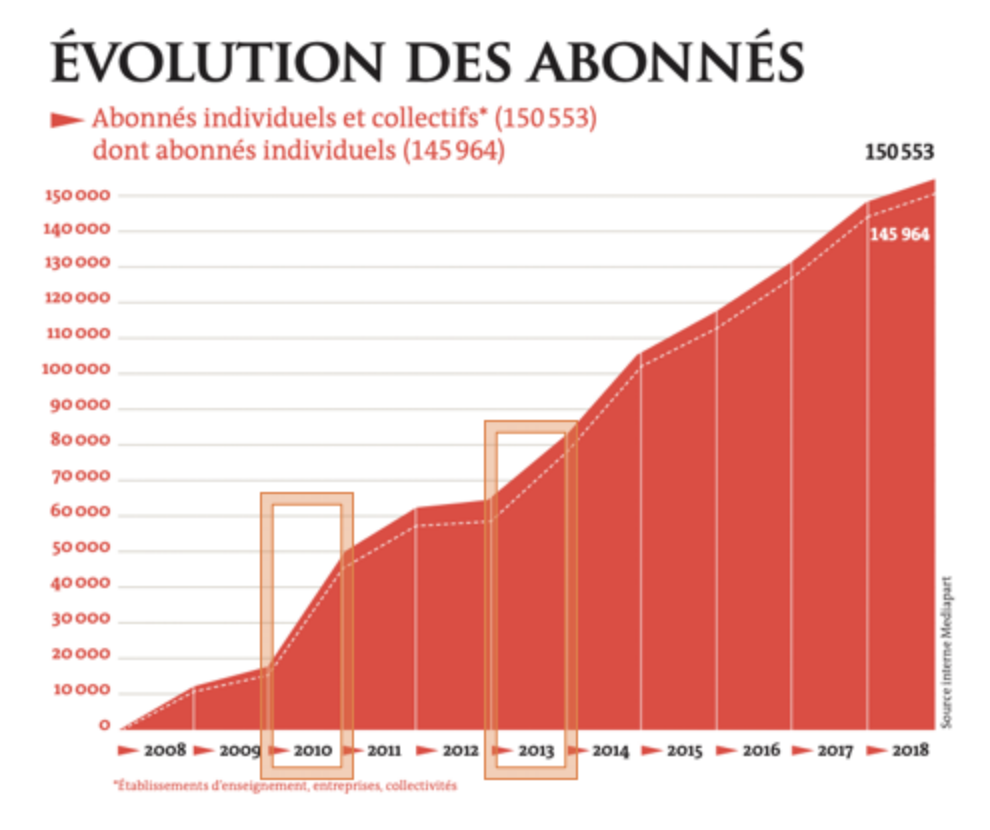

Mediapart took longer to reach popularity and today still is not a mass news organisation. Its hope is to be come a must-read publication and so far the evolution of subscribers exhibits the success of the strategy.

eldiario.es took a chance on a different model where payment was not a pre-condition for reading. “If you set your goals on advertising, they will always be short term. This is something platforms have exploited. But when you think that the goal is how to make people pay for something that could be free, you have to think long term,” Escolar explained. eldiario.es saw a jump in members in 2018 when they broke the story of how Cristina Cifuentes, a powerful politician who was the president of the Madrid region, had falsified her masters degree.

When eldiario.es was founded, its initial capital scarcely represented 20% of the initial capital of Mediapart (€600,000 vs €2.8 million). For this reason its bid required a diversification of income sources and for this the main channel was always advertising, although the contribution of no individual advertiser is above the contributions of its readers.

Six months after eldiario.es, the Spanish news site Infolibre was born. A journal with a similar focus and aimed at the same readership. Infolibre was born with a bigger editorial office (19 vs 12) and with a higher initial capital (€1 million). But they put their research behind a paywall and published breaking news for free, surrounded by advertising. Seven years later, eldiario.es editorial staff is four times greater than Infolibre and its budget, six times higher. eldiario.es has more than 34,000 members. Infolibre, less than 10,000 subscribers.

3. Journalist ownership but a professional approach.

To protect its editorial line, the founders decided that the capital would remain under the control of the journalists. At eldiario.es 70% is in the hands the founding journalists. At Mediapart, at the point of its creation, 43% was owned by the editorial staff and 17% was in the hands of a “society of readers”. To ensure public interest, the Mediapart founders created a non-profit foundation which purchased all of the shares.

When the editorial independence was guaranteed, both newspapers understood they needed a more professional business side. For this reason the admin staff grew faster than its editorial staff.

4. Innovators and left-wing leaders in the middle of information overload.

Both eldiario.es and Mediapart are projects that innovated in their own countries. They were born with reduced and scalable editorial offices. They set out to be leaders in the context of information overload. They took a chance on reader loyalty before volume and this can be seen on their website metrics.

eldiario.es is the first site in terms of frequent readers among the digital-born news sites in Spain and the fifth among legacy newspapers. Despite its contents being only for subscribers, Mediapart is already tenth in terms of frequent readers. In both cases, more than half of the readers access the newspaper directly or intentionally, without using side doors such as social media or search engines.

Another characteristic of both is that their readers identify themselves with a left-wing ideology. The average age of the Mediapart reader is slightly older tprobably due to the payment prerequisite. At eldiario.es, according to Digital News Report figures, the readership is younger and more female. It is important to point out that eldiario.es was the first Spanish news site to appoint a Gender Issues Editor.

5. Media discourse, transparency and participation.

Both eldiario.es and Mediapart take the concept of media discourse seriously, for binding the journalistic and business proposals. They permanently challenge their readers, explaining to them that their contribution allows them to produce the information they require. This request is based on a strict transparency policy which seeks to generate more trust. A strategy that is supplemented by a call for participation of the members/subscribers:

- At eldiario.es there are bimonthly columns in which the editorial office answers reader questions. Members receive a quarterly monograph magazine and are involved in thematic activities organised by the editorial team. Their comments in the editor’s notes stand out from the rest. In addition, many journalists respond to the comments in their own articles.

- At Mediapart subscribers are invited to write on their blog platform (the only part of the website with free access). A selection of posts then appear on the front page of the newspaper. The subscribers can communicate with journalists, assist with the Mediapart Live footage (a weekly program which is broadcast via YouTube) and with special events that are organised in the editorial office.

How to apply these lessons to Argentina

Is it possible to carry out projects like this in Argentina? What kind of adjustments must be made?

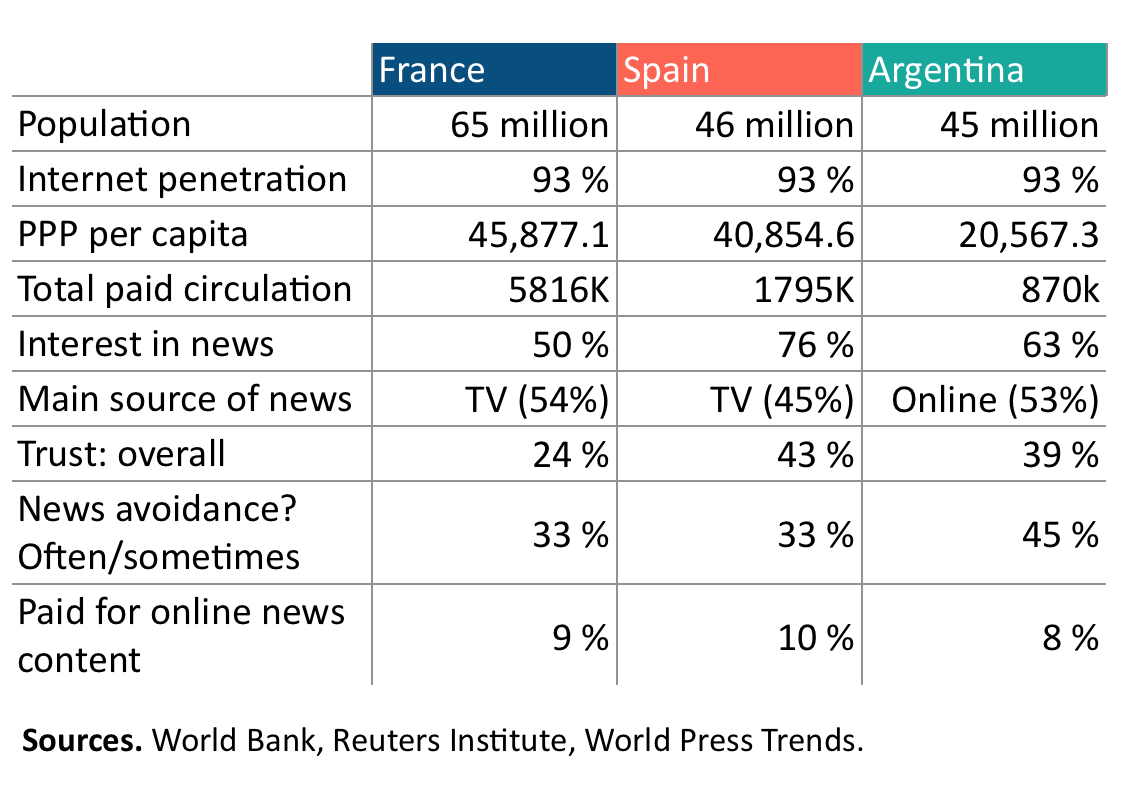

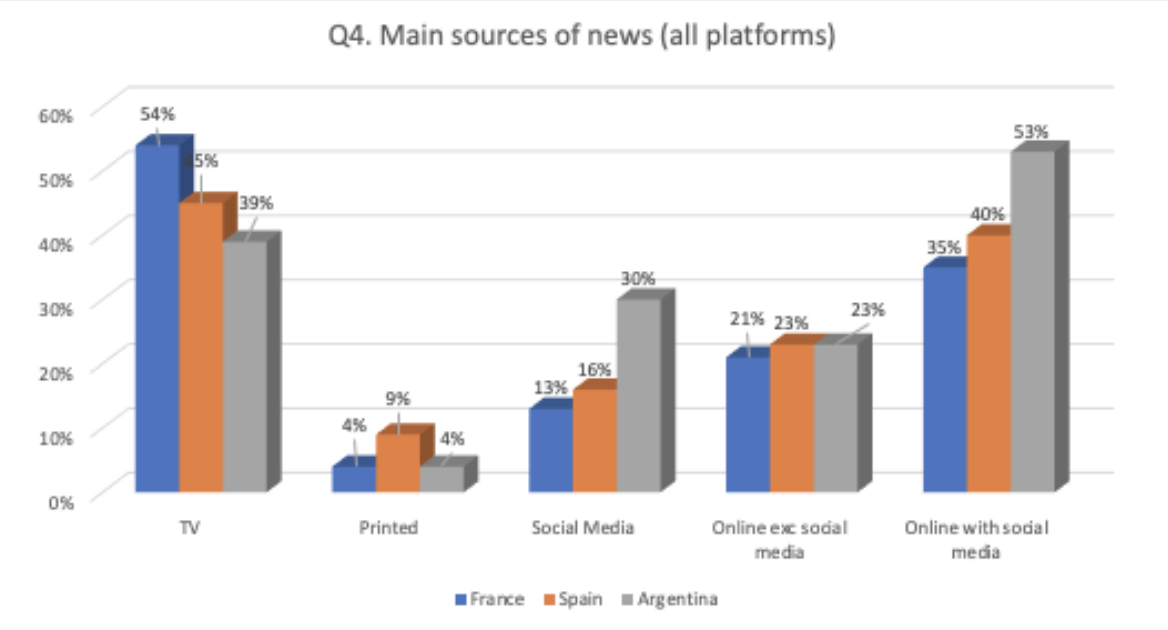

A quick look through the statistics shows structural differences between countries, but also some common points. In terms of interest and trust in news, Argentina is situated between Spain and France. Regarding paying for digital content, the percentage is similar in the three countries.

In Argentina, nevertheless, direct access to news front pages is higher (22%) than in Spain (20%) and France (17%). There is also a widespread habit of searching for news on the Internet. In recent times, more people say they look for prestigious sources to regain their trust.

This means there is a potential for new projects linked to these factors. Nevertheless, it has to be taken into account that in South America it's very rare to find newspapers focusing on reader revenue and therefore very little culture of paying for news. There is still a lot to be done.

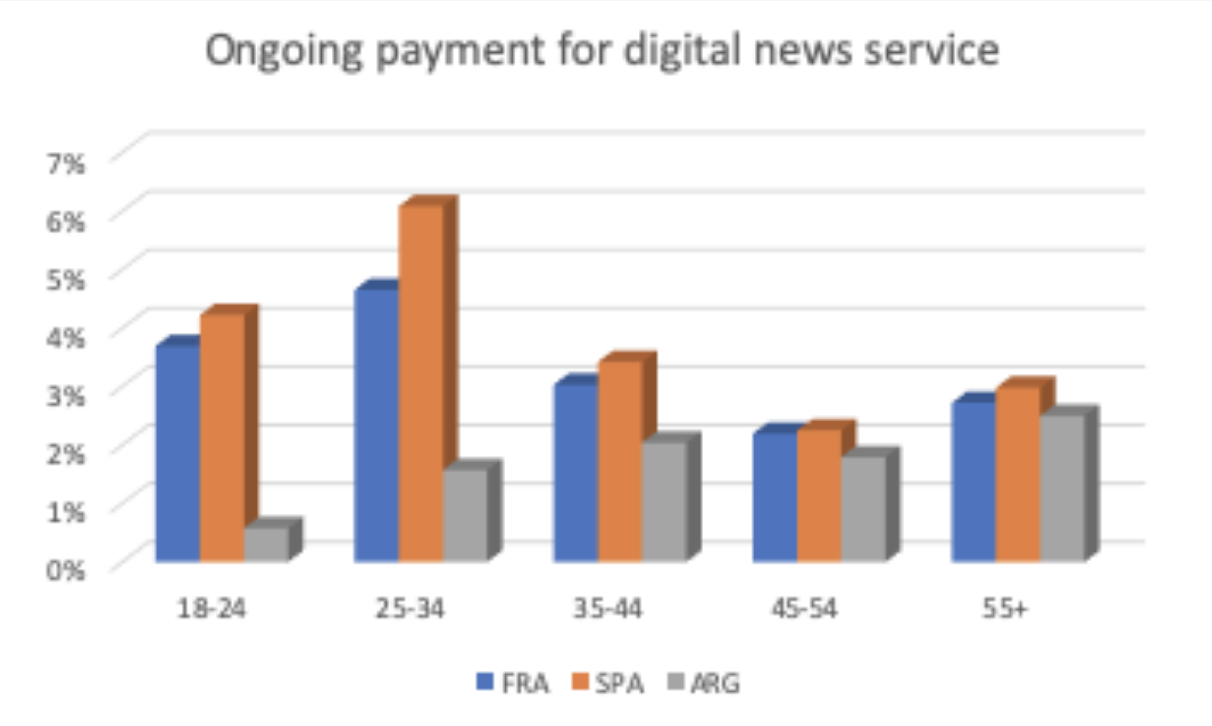

Tiempo was the first Argentinian newspaper to develop a membership model. Others followed its example and have even managed to reach a greater number of members: El Destape (launched by a journalist after they were sacked from TV within the framework of censorship complaints) is one and Futurock (an online radio station whose programming fuelled influencers on social networks) is another. This publication managed to reach the under 35-year-olds, a group that has rarely been targeted and one that rarely buys newspaper subscriptions (although they do pay for Spotify or Netflix).

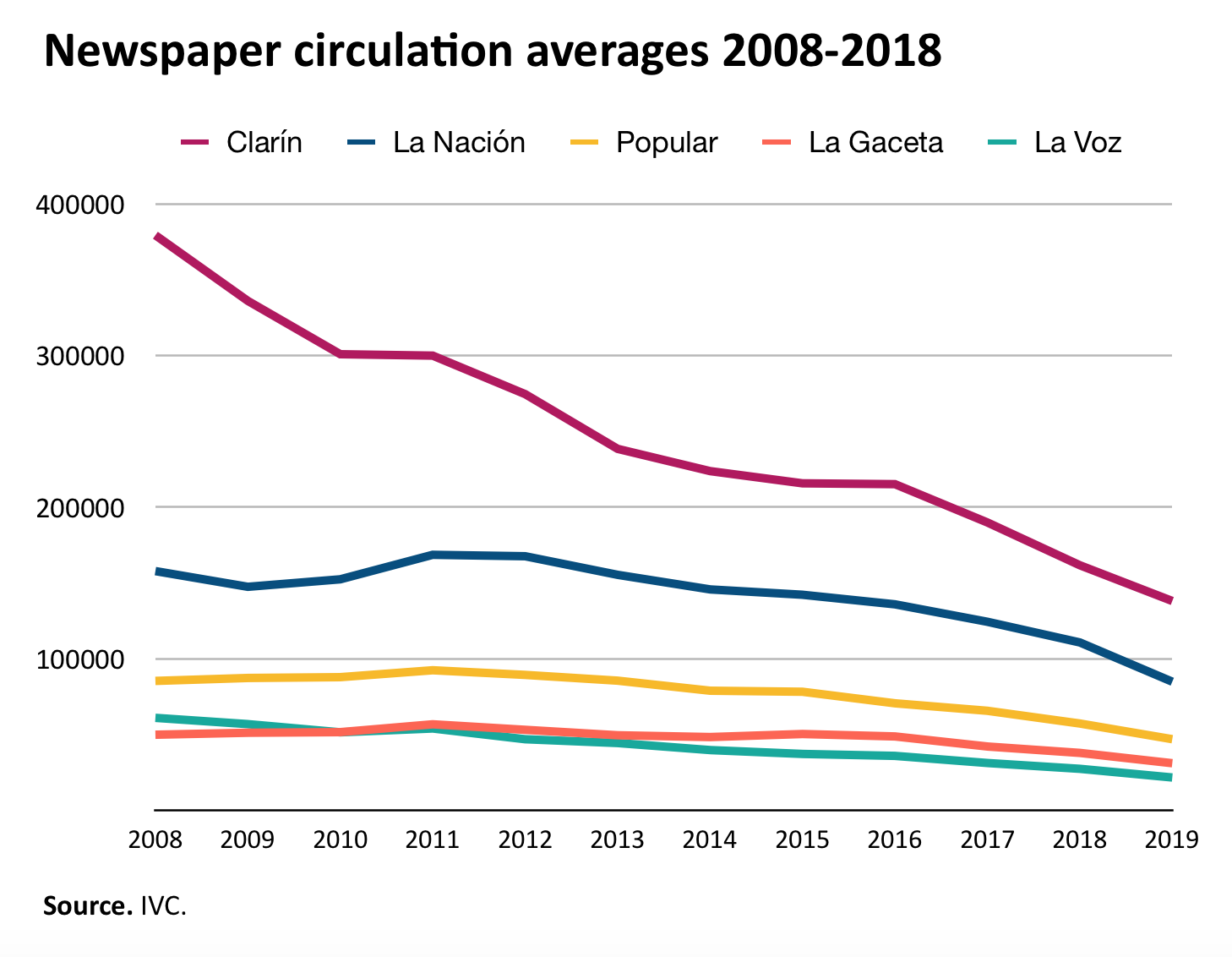

Another characteristic feature of Argentina is that government advertising has always been important for private news organisations. This is probably the reason why the drop in daily sales and private advertising did not affect their profitability for years.

In May 2017 traditional newspapers launched their first paywalls, which are softer and have lots of ways to avoid them. This caution is understandable. The main information site in Argentina, Infobae, is a site with free access whose revenues come from traffic and advertising.

The scenario described allows all types of interpretations. Some may pay attention to the differences and say that it's not possible to make an Argentinian newspaper like eldiario.es or Mediapart. Others will focus on the possible paths and opportunities and will try to adapt their ideas. What separates us is the risk that we are willing to take for journalism.

When Tiempo became a cooperative, our workers left us with no alternative. But the path we chose was the opposite to those studied in Europe. There was no initial capital. Our paper started with a large editorial office, no digital experience, and key areas could not be made more professional. Its cooperative history coincided with constant drops in GDP and the increase in unemployment and poverty, which generated a fall in consumption.

Nevertheless, the journal survived because it managed to identify with its readers and connect with their interests. Can it reinvent itself today to get out of its survival mode? Are the conditions in which the project was born a restriction to continue innovating at the pace required by the news ecosystem?

“Nobody should expect the revolutions of tomorrow to be led by traditional economic actors”, sociologist Julia Cagé wrote in her book Saving the Media (2016). What type of corporate structure will news businesses need to guarantee their independence? What form of approach should be used for readers? Which is the best strategy to keep them active? The questions are the same as those in the beginning but come after a learning process. Paraphrasing Héctor Schmucler, father of communication studies in Latin America, intellectual and journalistic work doesn’t have to give final answers but contribute to improving the questions.