The truth behind filter bubbles: Bursting some myths

Photo by Muhammad Raufan Yusup on Unsplash

A filter bubble is a state of intellectual or ideological isolation that may result from algorithms feeding us information we agree with, based on our past behaviour and search history. It's a pretty popular term that was coined by Internet activist Eli Pariser, who wrote about a book about it. However, as our Senior Research Fellow Richard Fletcher said in one of our recent seminars, academic research on the subject tells a different story about filter bubbles. Here's an edited transcript of that talk.

What is a filter bubble? Is it the same as an echo chamber?

People use services like Facebook, Twitter and Apple News to get their news. Some of the news that people see when they're using these platforms has been selected automatically by algorithms. Algorithms made this selection by using data that have been collected by platforms, based on our past use, and also data that we voluntarily give to platforms. Of course, the fear is that this could reinforce existing consumption patterns.

I personally think that echo chambers and filter bubbles are slightly different. An echo chamber is what might happen when we are overexposed to news that we like or agree with, potentially distorting our perception of reality because we see too much of one side, not enough of the other, and we start to think perhaps that reality is like this.

Filter bubbles describe a situation where news that we dislike or disagree with is automatically filtered out and this might have the effect of narrowing what we know. This distinction is important because echo chambers could be a result of filtering or they could be the result of other processes, but filter bubbles have to be the result of algorithmic filtering.

Why is the concept of filter bubbles so popular?

The filter bubble is a very powerful metaphor. Also the mechanisms which I described seem quite plausible. Everyone can understand them and they kind of make sense.

The idea of the filter bubble is very prominent and it has had an impact in the way we understand politics since the election of Donald Trump. A piece published at Wired magazine said that filter bubbles were destroying democracy, which is quite a bold claim. And as recently as in 2017 Bill Gates said that filter bubbles are a serious problem with news. Both claims show the kind of extent to which these ideas have taken hold from two sources that are not exactly technology sceptics. The existence of filter bubbles is widely accepted in many circles.

How do people get their news?

It's useful to start at the very beginning. So perhaps the easiest place to start is to ask whether people are actually using the internet to get news, and I think the answer to that question is a clear yes.

Most of the data that I’ve collected with a team of people at the Reuters Institute comes from the Digital News Report, our annual survey of news use in 38 different markets across five continents, mostly in Europe. Around 75,000 people responded to the survey. The polling was done by YouGov, but we designed the questionnaire.

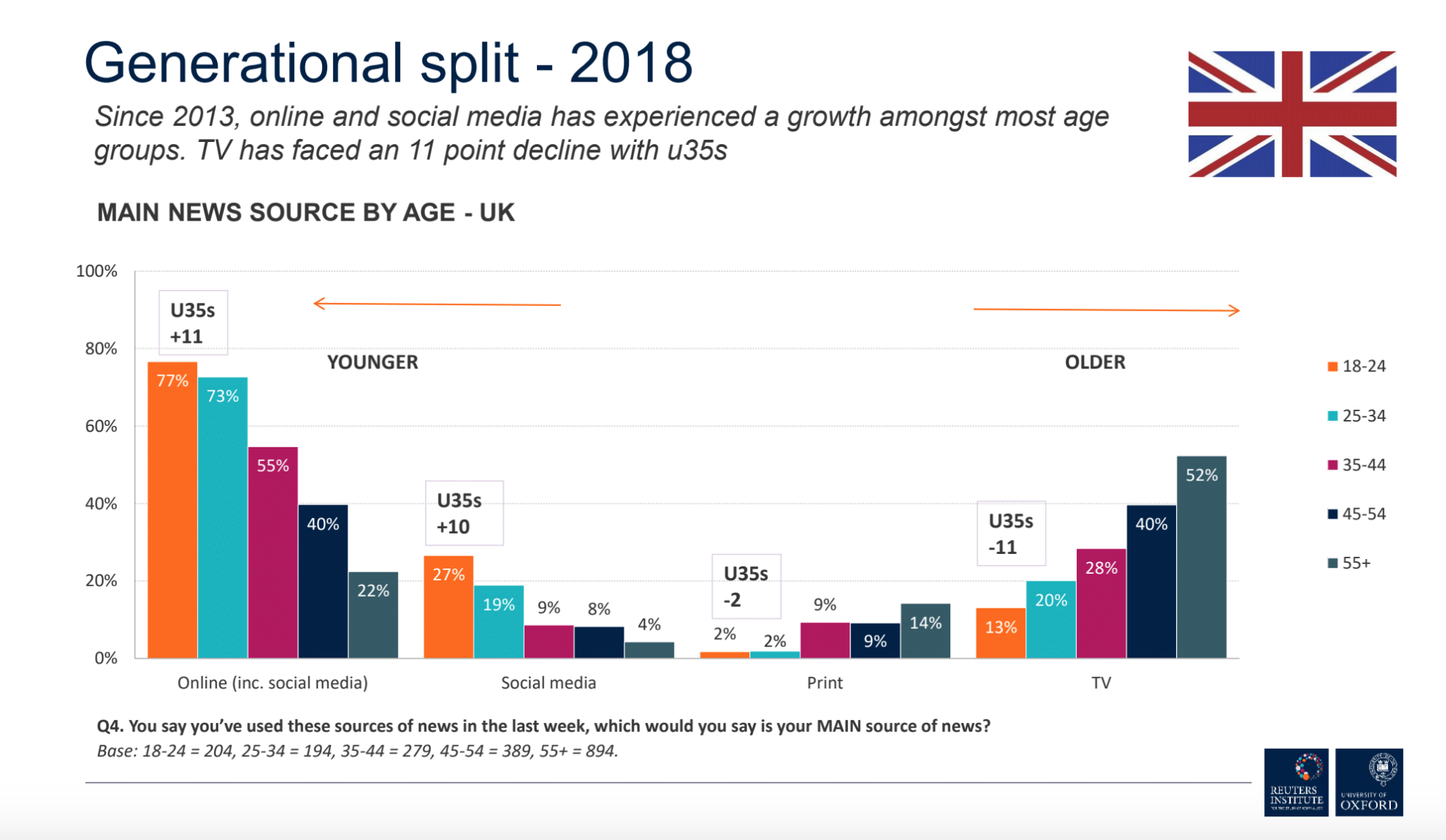

When we asked people what their main source of news is, roughly equal numbers of people say online and television. In some countries, TV is slightly ahead. In some countries, online is slightly ahead. But generally speaking, we see a very similar pattern with online and TV quite far ahead of print and radio.

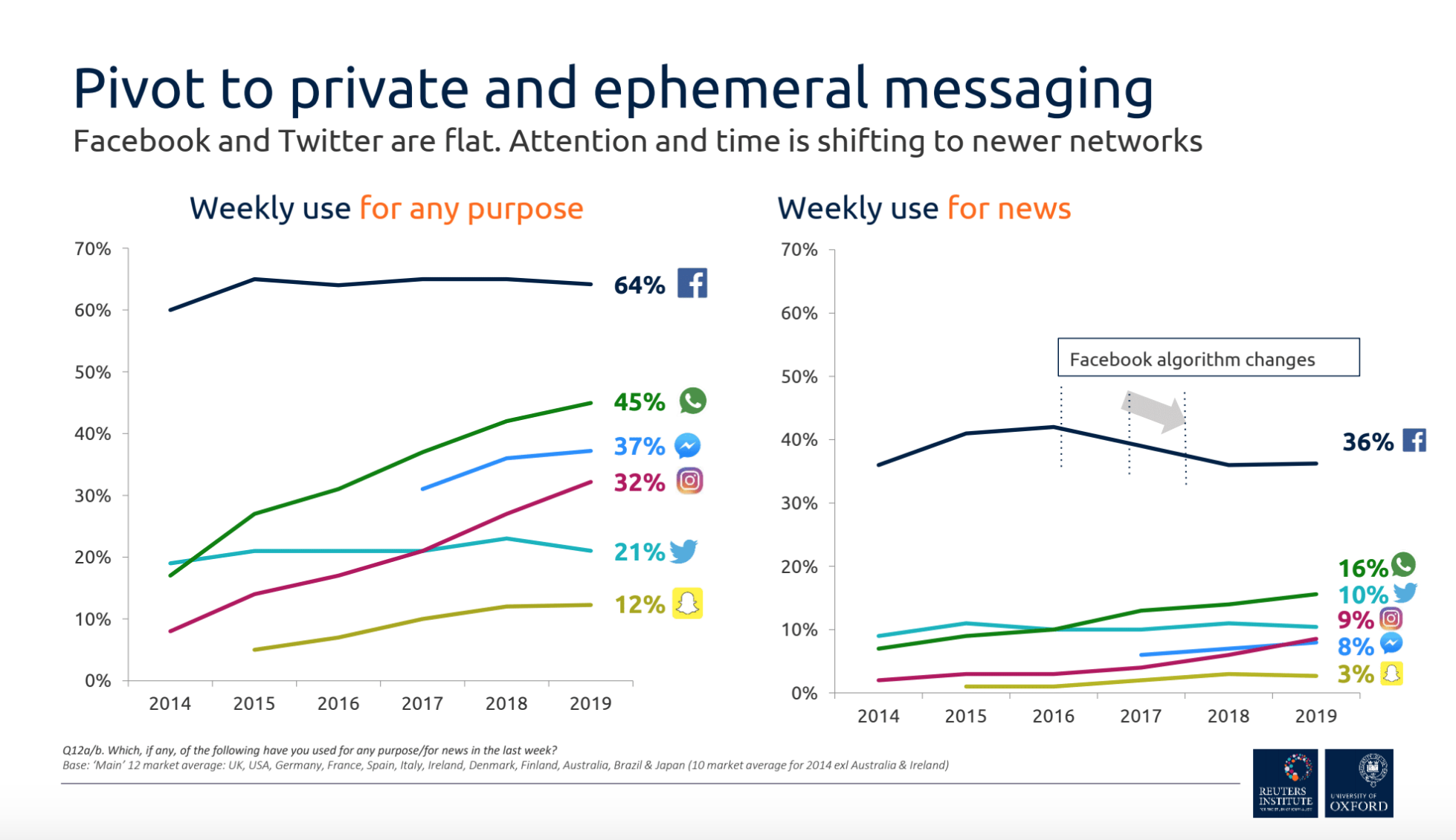

We also see differences when we look at age groups. TV is more likely to be the main source of news for people over 45. People under 45 are more likely to get their news online.We've been tracking the use of social media for news in different countries since around 2013. From around 2013 to 2016 there was consistent growth in the use of social media for news. So the proportion who said they used it each week rose from around 25% in 2013 to over 50% in 2016, but the figures have flattened off in the last three years.

If we dig a little bit deeper and look at the individual platforms, we can see that in most countries Facebook is the dominant platform for news use. Facebook use for news has hovered around 35% of the national population in countries where we have data going back to 2014. We saw a slight decrease from 2016 to 2018. During the same period, we've seen other networks such as WhatsApp becoming increasingly important for news use. These are very different kinds of social networks, but they are lumped under the social media category. So WhatsApp use for news has grown from around 10% to 16% in the last five years and Instagram has seen similar growth.

What other algorithms influence news consumption?

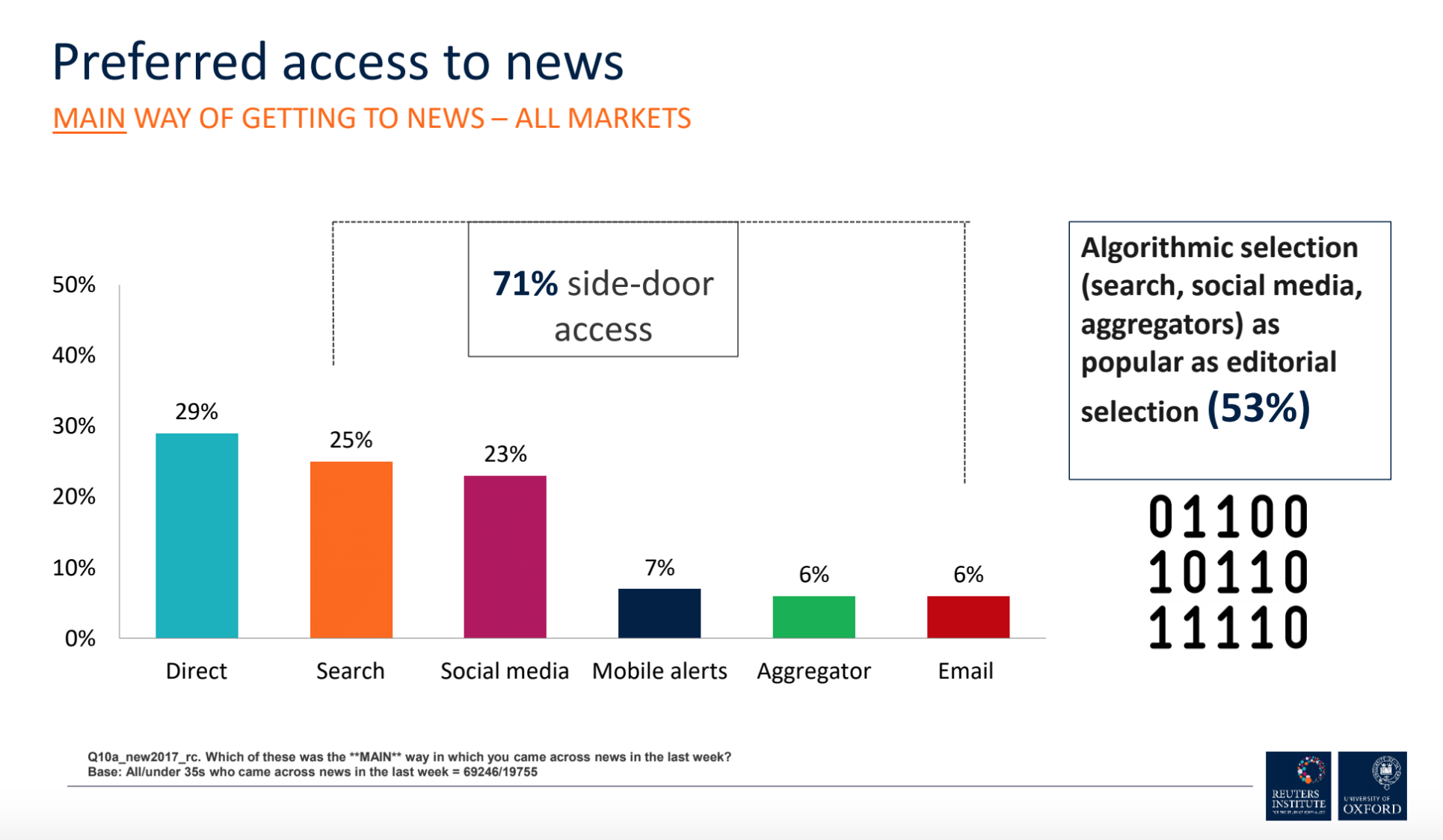

Search engines, email, mobile alerts and aggregators also rely on algorithms in some way to deliver news to people.

When we ask people what their main way of getting news online is, around a third say that it's by going directly to the websites and apps of news providers like BBC News or The Guardian in the UK. The other two-thirds say that their main way of getting news is by what we call a side door, which includes services like search, social, etc., and some of these services rely on algorithms to varying degrees.

So when it comes to filter bubbles, it's clear that the potential is there for us to be concerned. It's clear that algorithms and algorithmically driven services are very important, and a lot of people are using them to get news online.

How does personalisation work?

We can distinguish between self-selected personalisation and preselected personalisation.

Self-selected personalisation refers to the personalisations that we voluntarily do to ourselves, and this is particularly important when it comes to news use. People have always made decisions in order to personalise their news use. They make decisions about what newspapers to buy, what TV channels to watch, and at the same time which ones they would avoid.

Academics call this selective exposure. We know that it's influenced by a range of different things such as people's interest levels in news, their political beliefs and so on. This is something that has pretty much always been true.

Pre-selected personalisation is the personalisation that is done to people, sometimes by algorithms, sometimes without their knowledge. And this relates directly to the idea of filter bubbles because algorithms are possibly making choices on behalf of people and they may not be aware of it.

The reason this distinction is particularly important is because we should avoid comparing pre-selected personalisation and its effects with a world where people do not do any kind of personalisation to themselves. We can't assume that offline, or when people are self-selecting news online, they're doing it in a completely random way. People are always engaging in personalisation to some extent and if we want to understand the extent of pre-selected personalisation, we have to compare it with the realistic alternative, not hypothetical ideals.

It's important in particular not to romanticise the nature of offline news use for many people. One of the first studies we did in this area looked at how people self-select news online compared to offline. We looked at the extent to which audiences for particular news outlets in the UK overlapped with one another.

When people are offline, they stick to a couple of their preferred news sources. They dig very deeply into those news sources and tend not to deviate from them. Online, it's a bit different. Audiences for individual outlets are smaller because people spread their news consumption thinly across lots of different outlets.

Online news is often free, so people can sample news from different sources, and we can see that essentially self-selected personalisation is more prominent offline than it is online. This is why it's important to compare online news with the realistic alternative, and not an ideal.

What effect does social media have in people’s news diets?

Social media combines self-selected personalisation with pre-selected personalisation. We also know that people choose to follow certain news organisations and not to follow others. But it is also possible that algorithms might be hiding news from people which they're not interested in or from outlets they don't particularly like. People have a limited amount of time, so the decisions made by algorithms are going to affect what people see when they're using Facebook.

In order to understand how social media shapes news use, we compared the news diets of people who do not use social media with two other groups of people: one group who said they intentionally use social media for news and another group who said they don't intentionally use social media for news but see news when they're on social media for other purposes. So we took data from the UK, the USA, Italy and Australia, and studied the effect of using social media on different demographic groups and on different social networks.

Here’s what we found. People who use social media for news, particularly if they're using it for other reasons, are incidentally exposed to news whilst they're there and this boosts the amount of news that people use compared to the group that don't use social media at all. So the group that do use social media use more and more different online news sources.

Interestingly, the effect was stronger for younger people, perhaps because they're more adept at using social media and more active on these platforms. It was also stronger for people who don't have high levels of interest in the news. We also found the effect was stronger for YouTube and Twitter than it was for Facebook, which is important to keep in mind.

Our study highlights the fact that most people, particularly people who use social media, are not terribly interested in the news. And this becomes particularly important on the web, because this is a high-choice media environment. That makes it very easy for people who are not interested in news to essentially opt out of it. But because these same people often use social media, social media is incidentally exposing people to news even when they're not looking for it.

Do search engines create filter bubbles?

Search engines are different to social media. When people load up a search engine for news, they're intentionally trying to find news. But when you search for a particular topic, it's still possible that search engines will use algorithmic selection based on the data that has been collected about your past use. So the possibility again exists that when people log into search engines, algorithmic selection will trap them in a filter bubble.

We compared the news diets of people who search for news with the news diets of people who say they don't use search engines for news in four countries, and we studied the news diets that these two groups have in terms of what we call diversity and balance.

What we found is that a process of automated serendipity effectively diversifies people's news diets. People who use search engines for news on average use more news sources than people who don't. More importantly, they're more likely to use sources from both the left and the right.

People who rely mainly on self-selection tend to have fairly imbalanced news diets. They either have more right-leaning or more left-leaning sources. People who use search engines tend to have a more even split between the two.

What do other studies say on filter bubbles?

Our results are in line with different studies in the same area that have looked at this problem in a slightly different way. A study compared search results from different types of people, particularly people who were Republicans and Democrats in the US. And what this found essentially was that the results that people got when they searched for political topics were more or less the same. So there was no real evidence that people with different views are getting different search results.

One of the problems with relying on survey data is that people are not great at remembering what news sources they used. This has been a consistent problem for some time. So we tracked the web use of a panel of people in the UK and we compared situations when people go directly to news sources with situations when people go to news via Facebook, via Twitter and a range of other different services.

What we found was that the more people use direct access, the less diverse their news diet was. Not only people are using more sources of news when they get their news on social media. They're using lots of different sources, and the balance between those different sources improves with respect to diversity

This is a sort of summary of the work we've done in this area. But it's fairly representative of work in this area as a whole. There are numerous studies that either find weak evidence of filter bubbles or, at best, mixed evidence. There are almost no studies that find a very strong evidence of these kinds of effects.

Does social media encourage polarisation?

Even though we might be seeing more diversity when we use social media and search, it's possible that this diversity consists of more partisan or polarising news sources. A study published by a team of researchers in the US looked at people's exposure to their opposing side on Twitter. So if they were Republicans, they were fed lots of messages on Twitter from Democrats, and vice versa. They measured attitudes before and after this process and what they found is that as people paid attention to messages from the opposing side, their attitudes began to polarise, and they became more entrenched in their original beliefs.

We've approached the same issues slightly differently. We measured the level of polarisation that exists in different news environments in different countries. We looked at the audience of the particular news outlets and saw how different that audience was in terms of its composition of left- and right-leaning people as compared to the population as a whole. In the US, unsurprisingly, we found that Fox News has a news audience that is much more right-leaning than the population as a whole. The US is a polarised news environment because the bubbles of the audiences are much more dispersed than they are in some other countries.

What we can also do in those countries is compare online to offline. What we found when we looked at 12 different countries was that in eight out of 12 cases online news audiences are slightly more polarised, slightly more dispersed, than they were offline. In some countries, the numbers were either pretty much the same or offline is slightly more polarised. In general, though, online news environments do seem to be more polarised. Perhaps because there's much more incentive for some news outlets to produce more partisan content online.

Why shouldn’t we focus on filter bubbles?

Focusing on filter bubbles can cause us to misunderstand the mechanisms at play and might also be distracting us from slightly more pressing problems. The reason this is important is because some of these problems in some ways are connected with the use of platforms. It's not that the platforms are the cause, but they are part of the picture.

Most of the best available independent empirical evidence seems to suggest that online news use on search and social media is more diverse. But there's a possibility that this diversity is causing some kind of polarisation, in both attitudes and usage. This is interesting, because in some ways it's the opposite of what the filter bubble hypothesis predicted.

The hypothesis states that we'll actually get less diversity and there'll be negative consequences from that. So the end result might be the same. But the hypothesis fails to capture the mechanisms.

Of course, we know that platforms are changing the way they serve news to people all the time and the way that people are getting news is also changing. So we need to critically examine the effects of algorithmic selection on news use because what was true in the last few years isn't necessarily going to be true in the future.

Most importantly of all, and this is an argument that's taken from a recent book by Axel Bruns, the focus on filter bubbles may be preventing us from properly confronting the deeper causes of division in both politics and society.

While we keep examining platforms and their effects on news use, it’s crucial that we don't fall into this trap of ignoring some of the potentially more important factors that are creating some of the problems that we face.

If you want to know more...

- Check Richard's Google Scholar profile.

- Watch Richard's seminar here and listen to it here.

- Find Richard's slides in this link.

- Find most of the papers and books Richard mentions in this Twitter thread.