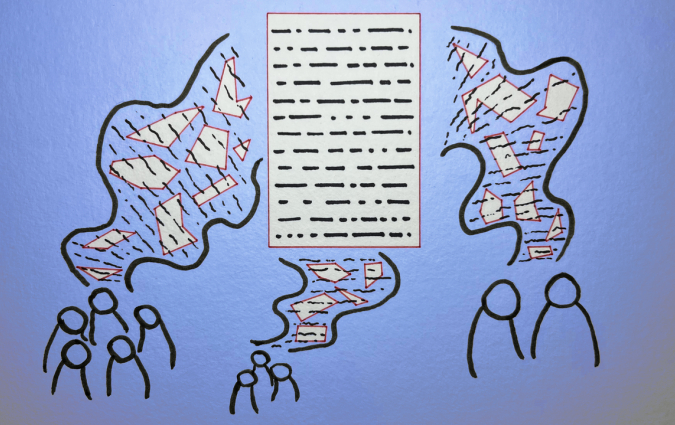

“Local media covered the floods before it was a catastrophe and after the spotlight is gone”

Flood victims gather to receive food handout in a camp, following the floods in Sehwan, Pakistan. REUTERS/Akhtar Soomro

Deadliest floods have devastated about one third of Pakistan this year, affecting 33 million people. "We've never seen anything like this," the country’s climate minister, Sherry Rehman, said.

On 25 August, Pakistan declared a state of emergency. Village after village was wiped out between June and August and millions of people were displaced. Southern provinces such as Sindh and Balochistan have been worst affected. Sindh, which houses Pakistan’s commercial capital of Karachi, received about eight times its average rainfall in August.

When a country is hit with devastation of such large proportions, local news outlets become indispensable. Ghulam Mustafa is the Director of News and Current affairs of Kawish Television Network News (KTN). KTN has transmitted in Singh language for 18 years. The Kawish Group is one of the biggest Sindhi media groups and reaches about 40 million people. The network started doing news programming in 2006.

I spoke to Mustafa recently about the role of Pakistan’s local news media throughout the floods: why they are important and how their work differed from the work of national and international media during the crisis.

Q. We always say that local news outlets are important. But can you give me specific examples for why they matter when it comes to colossal tragedies like the one Pakistan is facing right now?

A. Local media starts covering a story long before it turns into a catastrophe and continues to report it after the spotlight on the story is gone.

Here’s a good example. In May there was a drought in the Sindh province and farmers were protesting. The local media covered this extensively. I am not sure how much national attention we drew. But we did stories about how since Sindh is lower riparian and there is always a lack of water. The Sindh government also wrote to the federal government that the Punjab province to the north of Sindh should share water with the province. Nothing happened.

Suddenly, when monsoons started in June and July, it rained continuously for 5-7 days. And there were half a dozen spells like that. Within weeks, we went from drought to flooding, and we started reporting on that. There were people sitting on bridges with nothing to eat, and our government was angry that we were questioning their decisions or showing them in a bad light. Only later, when the national media realised the enormity of the situation, did they turn their attention to this.

What made matters worse was that excess water from the heavy rains in Balochistan also entered Sindh. These waters began submerging district after district in our province. When Sindh was getting flooded, many in the national media were focusing on the Asia Cup [a high profile cricket tournament. Only in mid-August did the national media report on the story, many weeks after we began following it.

I would say that we were ahead of the story. We needed to be proactive. People living in our province were depending on us to get information on where the water was and what to do about it.

Today, there are up to 100,000 internally displaced people in Pakistan due to the floods, and we are the ones reporting on what their needs are. Since the rains have stopped, few media houses nationally or internationally focus on Sindh.

Q. What are the unique features of local news coverage in Pakistan?

A. Language has a major sway in Pakistani media. Urdu is the national language and news in that language carries weight. Punjabi is another dominant language because stronger politicians are from the Punjab province. Sindh is the only language in Pakistan that has its own script [other than Urdu], and it includes Karachi, the commercial capital, where many media houses are headquartered. And yet we have to make twice the noise to make ourselves heard.

Let me give you an example of how influential national media is when it comes to the floods. Sindhi media was the first to report from the province’s third largest city Sukkur and we said that there was no place for the water to reach the ocean. When we started reporting on this, provincial chief Murad Ali Shah did a press conference and appealed to the Urdu media to please cover the floods in Sindh so that the federal government sent help and they could appeal to the international community.

Q. How can local news outlets add context to a breaking news story? Do you think they do it better than national and international outlets? Why?

A. I am not sure we do it better, but we know the local situation well. I will give you two concrete examples in the light of the floods.

First, rains have stopped for over a month. Why then is the water not reaching the ocean? We started reporting that people with money would build walls around their lands to keep the water from flowing into their property. That meant water had to enter the properties of poorer farmers.

Second, there were three major roads that connect Sindh to the rest of the country. The roads are broken, transforming the main commercial city, Karachi, into an island. This hit the exports of Pakistan very badly. There was no food supplies to Karachi and no industrial activity in the region. How will the cities be rebuilt again?

These are context-driven stories that we can do with nuance. These stories will benefit everyone nationally and internationally.

Q. When there is a big story like the floods, your staff take on roles beyond their traditional one as journalists. Could you explain how?

A. Regional media act as guides. National and international media journalists hire local journalists because we know where to get resources like a boat or where the hotels are. We know the sources and we know the language as well. During the floods, our journalists were also social workers. They were distributing food packets. They rescued people while reporting on them. The catastrophe is so big that our responsibilities also multiplied.

One of our reporters called me and said, “My city has drowned, there is water everywhere, how do I evacuate my family from there?” He was calling from Khairpur Nathan Shah in the Dadu district. I said that we would help him and his family with boats and other things, but I also asked him if he could consider staying back and reporting on this. He agreed as it was his responsibility to report on what was happening to the other 400,000 people who were stranded in the city. He knew the area very well. He told me that we can highlight the issues only if we are here.

Despite taking on all these roles, I think we failed to make an impression initially because even though Sindh language has about 6-7 TV channels, we were broadcasting to those who were drowning, and not to those who could come to save us.

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist, with a specific focus on human rights. Since 2011, she has reported from 12 countries across the world for outlets such as 'The New York Times', BBC, the 'Guardian', 'TIME', 'South China Morning Post' and 'The Hindu'. Samples of her work can be found here.