Journalism at COP26: the missing voices and a taste of a more inspiring way forward

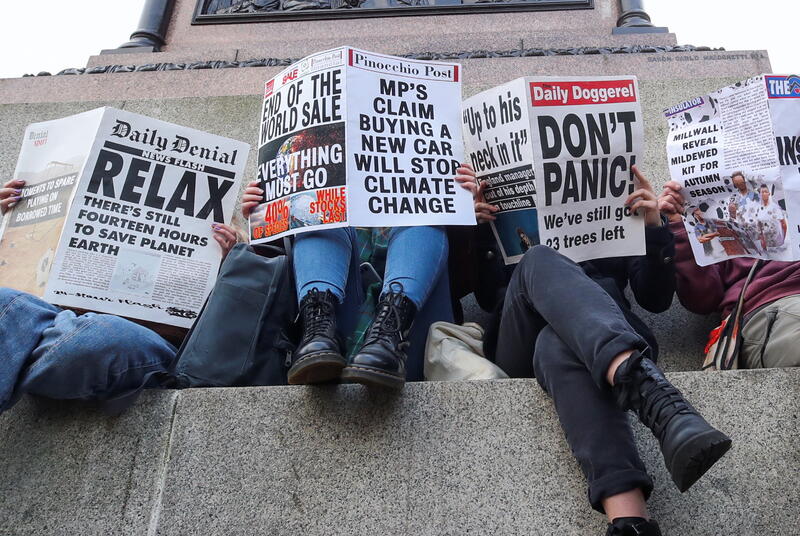

People demonstrate during COP26 in Glasgow. REUTERS/Yves Herman

COP26 was always going to be a story of keeping certain people out of the room. A global conference in the midst of a global pandemic is bound to result in asymmetric access: not even everyone who can afford to travel to one of the most expensive parts of the world will have the right vaccination status, accreditation and time to join the negotiations.

But COP26 was especially disappointing for the lack of imagination in getting over these barriers. In a year of video calls, not enough was live-streamed and there were not enough conversations with enough participants. And crucially, the media did not manage to create a common narrative, an urgent call to action that spoke to everyone.

This reflects the nature of the COP26 negotiations themselves, which often prioritised national narratives over global policy solutions: a tendency to look at how much other countries were or were not doing, rather than look for what total gains may be. The absence of leaders from three vital countries (Brazil, China and Russia) created an early impression that not all countries feel they are in this together.

The sight of British prime minister Boris Johnson batting away journalists' questions over the probity of his parliamentarians, instead of offering the host nation’s perspective and leadership on the COP26 summit, is a stark reminder that domestic politics and scandals are still what the media will report on first.

This is in many ways justified. The US media rightly pointed out that US president Joe Biden had to first reverse his predecessor Donald Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris accord, before pledging action in Glasgow and that all his actions can be undone again by the next president. Domestic politics matters.

But this must change. Climate change journalism is not something that can be pushed down the screen, to the back pages, to the end of the news bulletin. It’s already something that affects all aspects of our lives, whether we are ready to read about it or not.

As Lagipoiva Cherelle Jackson points out, journalists in Samoa who were told by editors a decade ago “not to alarm people” are now trying to explain just why cyclones are so much more frequent than they used to be, and why fishermen need to go out to sea several times a day to catch what they used to be able to catch in an hour.

To do this effectively, reporters must report on the immediate and also pull back, provide evidence and context, and outline the policy choices that have been made and must be made in the future by their governments and others.

It’s not the kind of story most newsrooms are designed to produce, but that may be a sign that newsrooms need to redesign themselves.

Reaching young people

Research from the Reuters Institute shows that young people in particular are feeling unfairly represented in the media and that there is too little coverage of the issues they care about. Recent debates on diversity in the media have also highlighted that many communities feel excluded or attacked by traditional framings.

Climate change offers the chance to rethink and to reach out. It’s a story that needs the media industry to rethink how it does its job and to engage with audiences it may have otherwise lost. It is place where real innovation does happen. Legacy brands invest in data visualisation to tell complex stories, traditional broadcasters use documentaries to show the changing world, and young reporters use social media to show just what is happening behind closed doors. And yet we need to go further.

The fringe events and protests outside the COP26 venue showcased voices the media has often ignored and offered new ideas on how to frame the story.

The Oxford Climate Journalism Network at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism is set up to help newsrooms rethink how they cover the climate crisis, not just through their environment desks but through all kinds of beats: politics, sport, health, travel, transport, fashion.

It will create a global network of journalists, editors and newsroom managers who can learn from each other and think of new ways of working. It doesn’t promise to offer all the solutions but a space to at least start thinking about how to approach a problem that concerns us all.

Join us:

- We are accepting applications from journalists for the first online course of our climate network. The deadline is Monday 15 November at noon, UK time, but we will reopen applications in March 2022.

- We are hiring a network controller and content producer to develop the course and associated materials.

- We will also soon be recruiting for other roles and offering up leadership courses.

- If you want a bespoke course for your news organisation on how to develop your coverage of the climate crisis, please send an email to philippa.garson@politics.ox.ac.uk and we'll get back to you to discuss fees, details and possible dates.