More than a year after it began, the Coronavirus pandemic continues to cast a dark cloud over the health of our communities – as well as that of the news industry. The crisis – complete with lockdowns and other restrictions – has hastened the demise of printed newspapers, further impacting the bottom line for many once proud and independent media companies. Our country pages this year are full of stories of journalistic lay-offs as advertisers take fright in the face of a global economic downturn. New business models such as subscription and membership have been accelerated by the crisis, as we document in this year’s report. But in most cases, this has still not come anywhere near making up for lost income elsewhere.

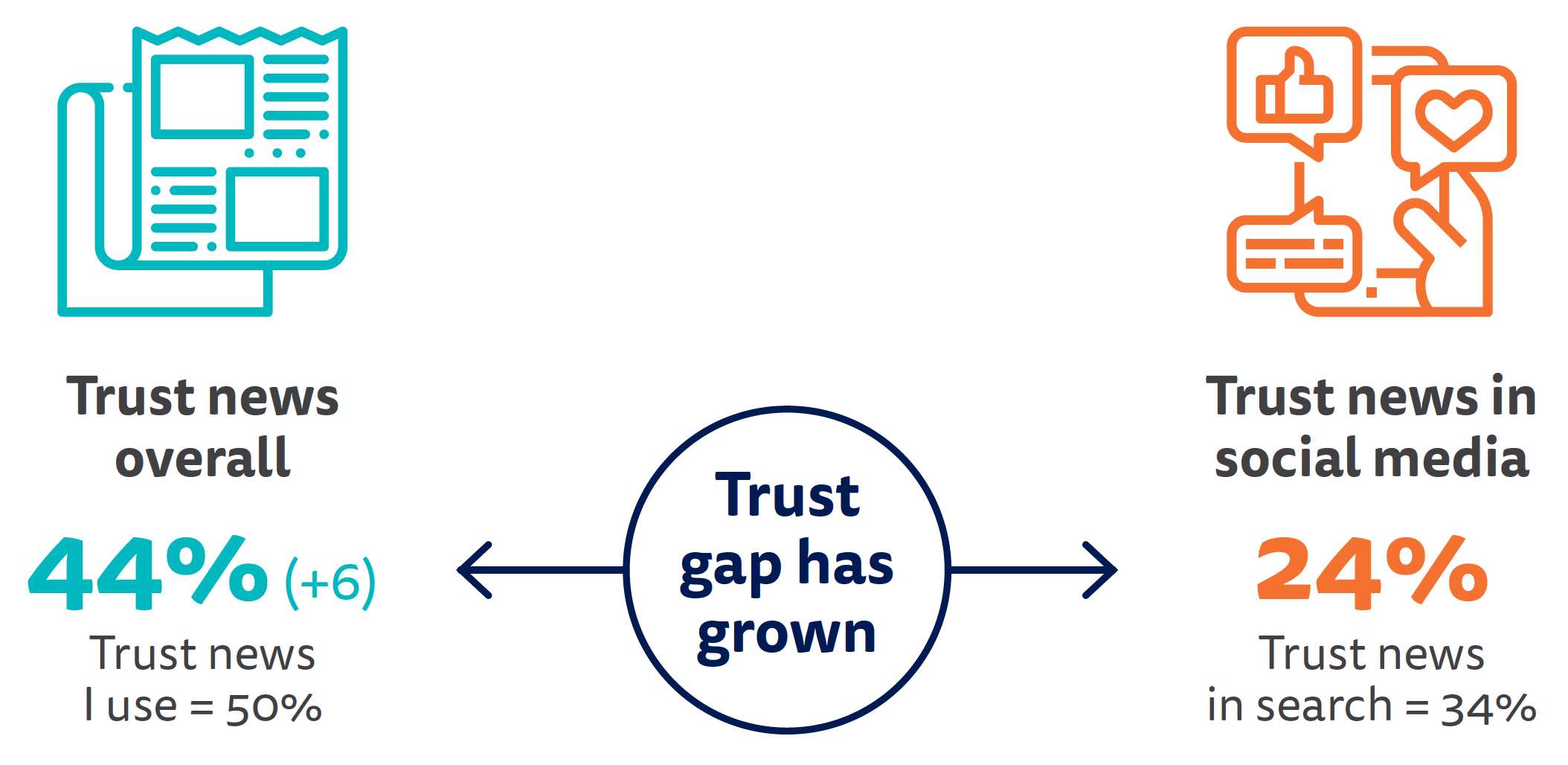

And yet, this crisis has also shown the value of accurate and reliable information at a time when lives are at stake. In many countries we see audiences turning to trusted brands – in addition to ascribing a greater confidence in the media in general. The gap between the ‘best and the rest’ has grown, as has the trust gap between the news media and social media. Of course, these trends are not universal and this year’s report also exposes worrying inequalities in both consumption and trust – with the young, women, people from ethnic minorities, and political partisans often feeling less fairly represented by the media.

The Capitol Hill riot in the United States and the global spread of false information and conspiracy theories about Coronavirus have further focused minds on where people are getting their news, which is why we have undertaken detailed research this year on understanding the role of different social networks for news and the complex ways in which they are being used to spread misleading and false information around the world.

This tenth edition of our Digital News Report, based on data from six continents and 46 markets, aims to cast light on the key issues that face the industry at a time of deep uncertainty and rapid change. Our more global sample, which includes India, Indonesia, Thailand, Nigeria, Colombia, and Peru for the first time, provides a deeper understanding of how differently the news environment operates outside the United States and Europe and we have tried to find new ways to reflect this, whilst recognising that differences in internet penetration and education will make some comparisons less meaningful. The overall story is captured in this Executive Summary, followed by Section 1 with chapters containing additional analysis and then individual country and market pages in Section 2 with extra data and industry context.

A summary of some of the most important findings from our 2021 research

-

Trust in the news has grown, on average, by six percentage points in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic – with 44% of our total sample saying they trust most news most of the time. This reverses, to some extent, recent falls in average trust – bringing levels back to those of 2018. Finland remains the country with the highest levels of overall trust (65%), and the USA now has the lowest levels (29%) in our survey.

-

At the same time, trust in news from search and social has remained broadly stable. This means that the trust gap between the news in general and that found in aggregated environments has grown – with audiences seemingly placing a greater premium on accurate and reliable news sources.

-

In a number of countries, especially those with strong and independent public service media, we have seen greater consumption of trusted news brands. The pattern is less clear outside Western Europe, in countries where the Coronavirus crisis has dominated the media agenda less, or where other political and social issues have played a bigger role.

-

Television news has continued to perform strongly in some countries, but print newspapers have seen a further sharp decline almost everywhere as lockdowns impacted physical distribution, accelerating the shift towards mostly digital future.

-

While many remain very engaged, we find signs that others are turning away from the news media and in some cases avoiding news altogether. Interest in news has fallen sharply in the United States following the election of President Biden – especially with right-leaning groups.

-

Elsewhere, we find that the media are seen to be representing young people (especially young women), political partisans, and – at least in the US – people from minority ethnic groups less fairly. These findings will give added urgency to those who are arguing for more diverse and inclusive newsrooms.

-

Despite more options to read and watch partisan news, the majority of our respondents (74%) say they still prefer news that reflects a range of views and lets them decide what to think. Most also think that news outlets should try to be neutral on every issue (66%), though some younger groups think that ‘impartiality’ may not be appropriate or desirable in some cases – for example, on social justice issues.

-

The use of social media for news remains strong, especially with younger people and those with lower levels of education. Messaging apps like WhatsApp and Telegram have become especially popular in the Global South, creating most concern when it comes to spreading misinformation about Coronavirus.

-

Global concerns about false and misleading information have edged slightly higher, this year, ranging from 82% in Brazil to just 37% in Germany. Those who use social media are more likely to say they have been exposed to misinformation about Coronavirus than non-users. Facebook is seen as the main channel for spreading false information almost everywhere but messaging apps like WhatsApp are seen as a bigger problem in parts of the Global South such as Brazil and Indonesia.

-

Our data suggest that mainstream news brands and journalists attract most attention around news in both Facebook and Twitter but are eclipsed by influencers and alternative sources in networks like TikTok, Snapchat, and Instagram. TikTok now reaches a quarter (24%) of under-35s, with 7% using the platform for news – and a higher penetration in parts of Latin America and Asia.

-

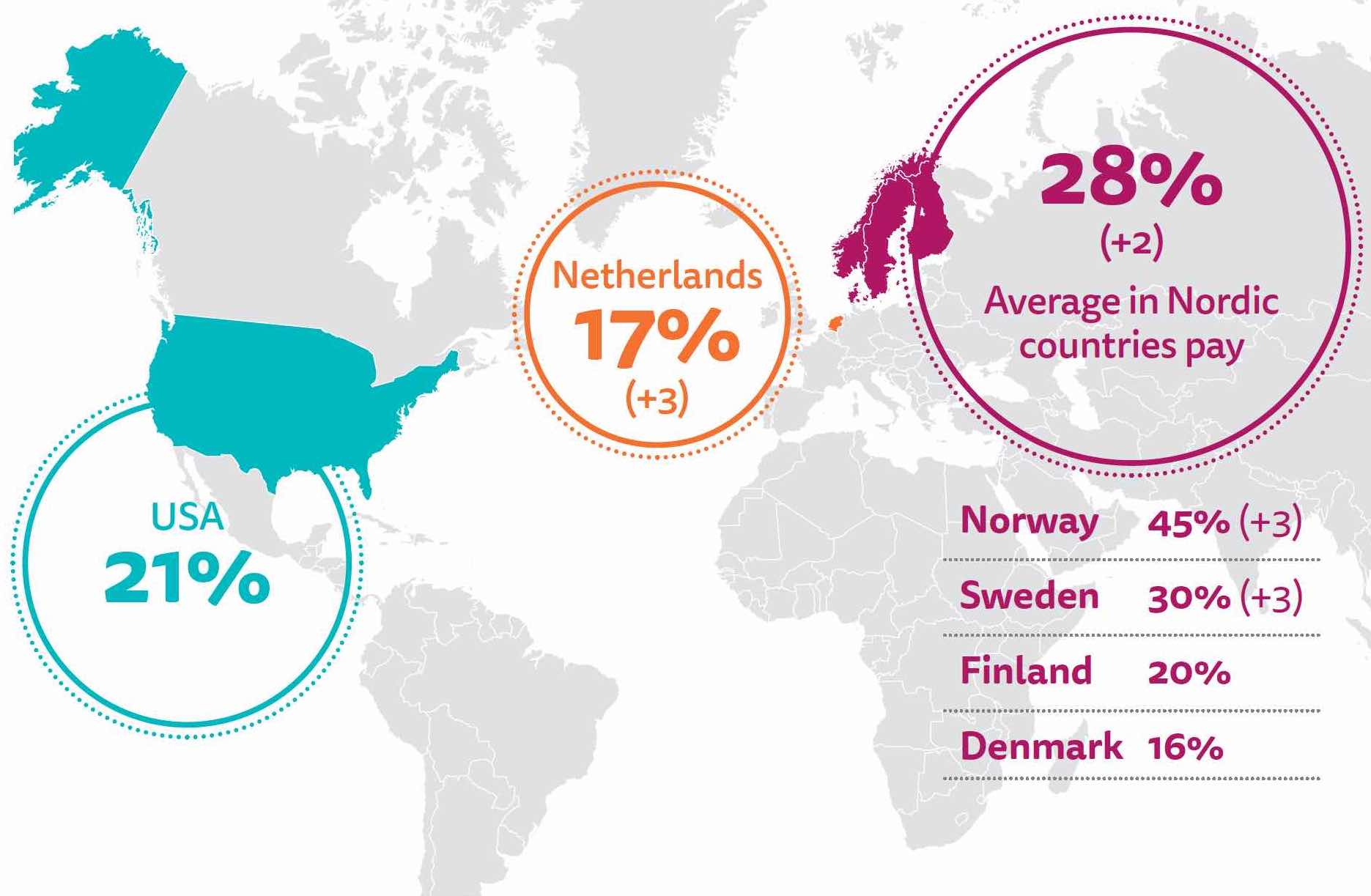

We have seen significant increases in payment for online news in a small number of richer Western countries, but the overall percentage of people paying for online news remains low. Across 20 countries where publishers have been pushing for more online payment, 17% have paid for any online news in the last year – up two percentage points. Norway continues to lead the way with 45% (+3) followed by Sweden (30%), the United States (21%), Finland (20%), the Netherlands (17%), and Switzerland (17%). There has been less progress in France (11%), Germany (9%), and the United Kingdom (8%).

-

In most countries a large proportion of digital subscriptions go to just a few big national brands – reinforcing the winner takes most dynamics that we have reported in the past. But in the United States and Norway we do find that up to half of those paying are now taking out additional subscriptions – often to local or regional newspaper brands.

-

More widely, though, we find that the value of traditional local and regional news media is increasingly confined to a small number of subjects such as local politics and crime. Other internet sites and search engines are considered best for a range of other local information including weather, housing, jobs, and ‘things to do’ that used to be part of what local news media bundled together.

-

Access to news continues to become more distributed. Across all markets, just a quarter (25%) prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app. Those aged 18–24 (so-called Generation Z) have an even weaker connection with websites and apps and are almost twice as likely to prefer to access news via social media, aggregators, or mobile alerts.

-

While mobile aggregators play a relatively small part in the media eco-system of Western countries, they have a powerful position in many Asian markets. In India, Indonesia, South Korea, and Thailand a range of human- and AI-powered apps like Daily Hunt, Smart News, Naver, and Line Today are playing an important new role in news discovery.

-

More widely, the use of smartphone for news (73%) has grown at its fastest rate for many years, with dependence also growing through Coronavirus lockdowns. Use of laptop and desktop computers and tablets for news is stable or falling, while the penetration of smart speakers remains limited in most countries – especially for news.

-

Growth in podcasts has slowed, in part due to the impact of restrictions on movement. This is despite some high-profile news launches and more investment via tech platforms. Our data show Spotify continuing to gain ground over Apple and Google podcasts in a number of countries and YouTube also benefiting from the popularity of video-based and hybrid podcasts.

Changing news consumption and the impact of coronavirus

The pandemic has affected markets at different times and to different degrees. Our polling was conducted when the UK and Ireland were in full lockdown, the United States and Brazil were operating under state-by-state rules, while Australia, Taiwan, and Japan were mostly free of internal restrictions. Common patterns may be hard to discern, but it is instructive to look at parts of the world that have been badly and collectively affected. In this respect, Western Europe provides a good case study.

Across a number of European countries, we find that consumption of television news is significantly higher than a year ago when no restrictions on movement were in place. This is not surprising, given that so many people have been stuck at home, but has reaffirmed the importance of a medium that is accessible, easy to consume, reaches a wide range of demographics, and is mostly well trusted. Twenty-four-hour news channels such as Sky News (+5 percentage points) in the UK and n-tv (+6pp) in Germany are amongst the brands to have benefited.

In some of these countries, there has been an even bigger switch in underlying preference (main source) towards TV and away from online. In the UK, the proportion selecting TV news as main source was up to 36% (+7pp) and in Ireland 41% (+8pp). In both countries we see increased TV reliance across age groups, though older people, of course, still have a much greater underlying preference for TV news.

It would be wrong to over-emphasise any temporary bump in TV consumption given the longer term shift towards digital sources but it is a reminder of the continuing draw of video-based storytelling as well as the strength of traditional news brands. But perhaps the most striking finding around consumption has been the extent to which people have placed a premium on reliable news sources in general, not just on TV.

Trusted brands also do better online

It is important to note that our last survey captured a moment in time pre-pandemic (January 2020), and a year later in January 2021 we captured another, when the impact of Coronavirus varied across countries. In the intervening time we know that most news brands reported at various times vastly increased usage – especially during the first months of the crisis. Our data, a year on, perhaps show which brands may have held onto those gains most effectively – giving a hint of more lasting changes.

In our analysis of fourteen European countries (listed underneath the chart below), we note that some of the most trusted news organisations – including commercial and public media brands – have retained quite significant extra online audiences in terms of online reach. On average, brands with lower trust scores have done less well by comparison. This trend is strongest in Sweden, Austria, Ireland, and Norway, a little less so in Finland – perhaps because all big brands are relatively well trusted there.

Looking across our data, although the overall link between trust and increased reach is weak, the key beneficiaries in terms of weekly use seem to be big commercial and public service news brands – especially those that already had a reputation for reliable online news. This means brands like VG in Norway (+9pp), TV2 in Denmark (+8pp), and MTV News (+7pp) in Finland. Others that have done better than average include The Irish Times (+7pp), Der Standard in Austria (+5pp), and Le Soir in Belgium (+4pp). Many of these changes have come in markets where the overall consumption of online news has not increased overall year-on-year.

Public service media websites have performed particularly well, perhaps because they have been able to use their reach via TV and radio to promote more detailed information online. Public media websites have provided extensive local breakdowns of Coronavirus data, alongside fact-checking and other explanations.

These gains have not been generally reflected in countries where public broadcasters are less well trusted. Outside Europe we also find examples of PSBs that have enhanced their reach during this crisis, including ABC in Australia

This has given a boost to a sector whose legitimacy and funding have been threatened by a combination of changing consumer behaviour and attacks by populist and right-wing politicians. Before the crisis, for example, Boris Johnson’s Conservative government in the UK was considering turning the BBC into a subscription operation, now MPs are recommending any change to funding arrangements should be shelved until at least 20381.

Interest flags in ‘depressing’ coronavirus news for some

Interest in news has risen in some countries that have been badly affected by the crisis. It is also higher in people whose lives have been directly impacted, but on average across countries we find that levels of interest (59%) have not risen over the last year – with young people and those with lower education still paying less attention.

If we take a longer term perspective, we actually see a decline in news interest in a number of countries – despite the turbulent times in which we live. The proportion that says they are very or extremely interested has fallen by an average of five percentage points since 2016 – with a 17 percentage point drop in Spain and the UK, 12 points in Italy and Australia, and eight in France, and Japan. There has been little or no decline in countries such as Germany and the Netherlands.

More than a year on, intense interest in the subject appears to be waning, with many in our focus groups saying they often find the news repetitive, confusing, and even depressing:

United States a special case

In some countries, lower interest may be as much to do with changed politics as the Coronavirus crisis itself. Interest in the news in the United States has declined by 11 percentage points in the last year to just 55%. To some extent this is not surprising as our poll was conducted after the turbulent events on Capitol Hill in January and the departure of Donald Trump. But our data show signs that many former Trump supporters may be switching away from news altogether. Almost all of this fall in interest came from those on the political right.

Since January, right-leaning TV networks in the US such as Fox News have lost a significant chunk of their audience but so too have liberal outlets like CNN. Some commentators have long predicted that ‘Journalism’s Trump bump might be giving way to a slump’, as online ratings also fell dramatically in February 2021.2

Decline in interest in mainstream news remains a huge challenge at a time when societies are facing such a set of existential threats to health and prosperity. The challenge for media companies is how to re-engage that interest without dumbing down or resorting to sensationalism, which in turn can damage trust.

Coronavirus another ‘nail in the coffin’ for print

Print publications have been badly affected by COVID-19, partly due to restrictions on movement and partly due to the associated hit to advertising revenue. Countries that have traditionally had high levels of circulation, such as Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, have seen some of the biggest falls. Concerns about contamination from printed copies sold at newsstands affected daily sales in many countries.

The crisis has had a devastating impact on freesheets that are mainly distributed to commuters on public transport. In the UK, for example, distribution of both Metro and the Standard fell by around 40% year-on-year according to industry data. More widely, the impact of Coronavirus is driving more industry consolidation but also accelerating plans for digital and workflow transformation.3 As one example, News Corp Australia suspended the print editions of 112 suburban and regional mastheads, axing almost 1,000 jobs. Our country pages document how both local and national publications have been affected by furloughs, layoffs, and closures, reducing the ability to inform citizens at a time of greatest need.

Paying for news and the shift to reader revenue

The last year has also seen more quality journalism go behind paywalls, as print and digital-born publishers turn to subscription, membership, and donations to reduce their reliance on advertising – which online continues to go primarily to Google and Facebook. El País in Spain, El Tiempo in Colombia, and News 24 in South Africa are amongst those to have started their paywall journeys in the midst of the pandemic.

Overall progress remains slow. Across 20 countries where publishers have been actively pushing digital subscriptions – and that we have been tracking since 2016 – we find 17% saying that they have paid for some kind of online news in the last year (via subscription, donation, or one-off payment). That’s up by two percentage points in the last year and up five since 2016 (12%). Despite this, it is important to note that the vast majority of consumers in these countries continue to resist paying for any online news.

We find most success in a small number of wealthy countries with a long history of high levels of print newspaper subscriptions, such as Norway 45% (+3), Sweden 30% (+3), Switzerland 17% (+4), and the Netherlands 17% (+3). Around a fifth (21%) now pay for at least one online news outlet in the United States, 20% in Finland, and 13% in Australia. By contrast, just 9% say they pay in Germany and 8% in the UK.

Proportion that paid for any online news in the last year - selected markets

The following chart provides more background on the development of paid content in some of these 20 markets. It shows, for example, how divisive elections can produce a bump in subscriptions; after the election of Donald Trump in 2016, we saw a surge of new subscriptions to publications like the New York Times and Washington Post. Progress has been faster in Norway and Sweden, partly because they are small markets protected by language, but also because a limited number of digitally committed publishers have almost all sought to charge for online news. More recently, across countries, publishers have added or tightened paywalls, using data to target new customers and linking messaging to the importance of trusted content. These approaches may have helped drive recent increases in countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands. COVID-19 may also have contributed to the perceived value of some quality journalism. But in countries such as France and the UK the headline rate has been hard to shift, even if a handful of publishers are attracting new subscribers running into tens of thousands.

Subscription winners around the world

This year we asked respondents in a number of countries to tell us how many subscriptions they have taken out and which news brands they pay for.

We have previously highlighted a winner takes most dynamic and it is a similar story this year. Getting on for half of all subscribers in the United States (45%) pay for one of the New York Times, Washington Post, or Wall Street Journal, according to our data. In the UK, The Times, Telegraph and Guardian account for over half (52%) of those who currently pay, while in Finland, we find that almost half of subscribers (48%) pay for just one publication, the leading broadsheet Helsingin Sanomat. In Germany, which has long had a more competitive market with strong regional titles reaching a significant national audience, the pie is more evenly split between a range of national titles, including the tabloid Bild as well as the up-market Der Spiegel, Die Zeit, FAZ, and Süddeutsche Zeitung, while inSpain we find a mix of national titles and smaller digital-born outlets pursuing membership models.

One striking finding from our survey this year is the difference in contribution made by local and regional publications across countries. In Norway, 57% of subscribers pay for one or more local outlets in digital form. This compares with 23% in the United States, but just 3% in the United Kingdom.

Sweden (37%) and Finland (31%) also have a high take-up for local publications amongst subscribers. These data give us much better insights into why subscription levels in Nordic countries, and to some extent in the United States, are so much higher than elsewhere – namely the contribution of local and regional news. In English-speaking countries such as Australia and Ireland we find a significant proportion of subscribers paying for foreign titles such as the New York Times and The Times of London, often at a discounted rate. In terms of demographics, those taking out online news subscriptions tend to be richer, more educated, and older, with an average age ranging from 40-45 in Spain to over 55 in Denmark.

Multiple subscriptions are becoming more common in mature markets

Across our sample, the majority of those paying take out just one subscription, but in the United States the median is now two. This means just over half of those paying take out subscriptions to more than one title. This may be because in the US there is now an increasingly wide range of subscription and membership options from large publishers and local papers – as well as for individual journalists (e.g. Substack newsletters or ‘channel memberships’ to YouTube creators). A growing minority of Americans, we find, now combine a national publication with a local provider or with a specialist publisher of some kind. Aggregators like Apple News+ are also playing a part. Elsewhere, we find respondents combining a national title with an international one such as the New York Times, often at a discounted price.

Subscribes to nine publications including the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Indianapolis Star, The Economist, ProPublica, and the Guardian

Subscribes to Wall Street Journal, The Athletic (Sport) Centre Daily Times (Pennsylvania), and the National Review (conservative opinion magazine/website)

The pattern of multiple subscriptions seems similar to the way in which video on demand streaming services have developed, with a minority of the most interested taking out multiple subscriptions, or combining a dedicated premium subscription product (e.g. Netflix, Disney+) with a subscription to an aggregator or bigger bundle (e.g. Amazon Prime or YouTube Premium).

Future prospects

Subscriptions are beginning to work for some publishers but it is not clear that they will work for all consumers. Most people are not interested enough in news, or do not have sufficient disposable income to prioritise news over other parts of their life. Others may resist because they enjoy being able to pick from multiple sources and do not wish to be confined to one or two publications.

Amongst those who are not paying, just a small minority say they are likely to do so in the future for online publications that they like. Rates are higher in countries that are already some way down the line (16% in Norway) when compared with those that aren’t (8% in the UK) which suggests that (a) there is still some room for growth even in mature markets, and (b) abundant supply of free news, whether from commercial or public service providers, is a key factor for some of those not currently paying.

The future of local media

The finding that some people in some countries are prepared to pay for local news in digital form will be encouraging to those who worry about the sustainability of local news media. A Poynter analysis found that, since Coronavirus began, more than 60 local news organisations in the United States have shuttered or temporarily closed.4 But our survey also shows the extent of the disruption suffered by local media driven in large part by internet platforms – and the scale of the challenge they now face.

While people still think of newspapers as the best destination for local politics, in other areas search engines, internet marketplaces, or social media are now considered better or more convenient. Looking at the UK, as one example (see following chart), audiences are more likely to use search engines and other internet sites as the best place to access weather or local jobs information, along with social media for recommendations about ‘things to do’. Newspapers are not even the primary location for information about COVID-19, which has become easily accessed via a data visualisation in Google search results, from a social media feed, or from an official government website. By contrast, in Norway, local newspapers are seen as the ‘go-to’ source for politics (71%), crime (73%), Coronavirus news (53%), and things to do (46%). Only for weather and local jobs do Norwegians find greater convenience with internet sites or search engines. By this measure, Norwegians value their local newspapers more than twice as much as the British in every category.

Our research this year also shows a link between how attached people are to their local community and levels of local news consumption. Respondents in both Austria and Switzerland are amongst those countries that feel most strongly attached and – like Norway – these are also countries where local news consumption tends to be higher and the value of local newspapers is more keenly felt. There may be many reasons for this, including geography, language, demographic make-up, or the extent of political control that is exercised at a local level. It is a different story in the UK (48% attached) and Japan (37%), which both have more centralised political systems and where more people live in big cities.

None of this is to suggest that publishers in countries with more attachment are not also suffering from the impact of digital disruption. We see blind spots and decline in most markets, but the fact that local newspapers in Norway are still valued for a bundle of different information services gives them a stronger chance of persuading people to pay for online news. In the UK, by contrast, where internet and social media sites play a bigger role in media diets, there is more competition from local TV, and getting people to pay has proved much harder.

Should governments step in?

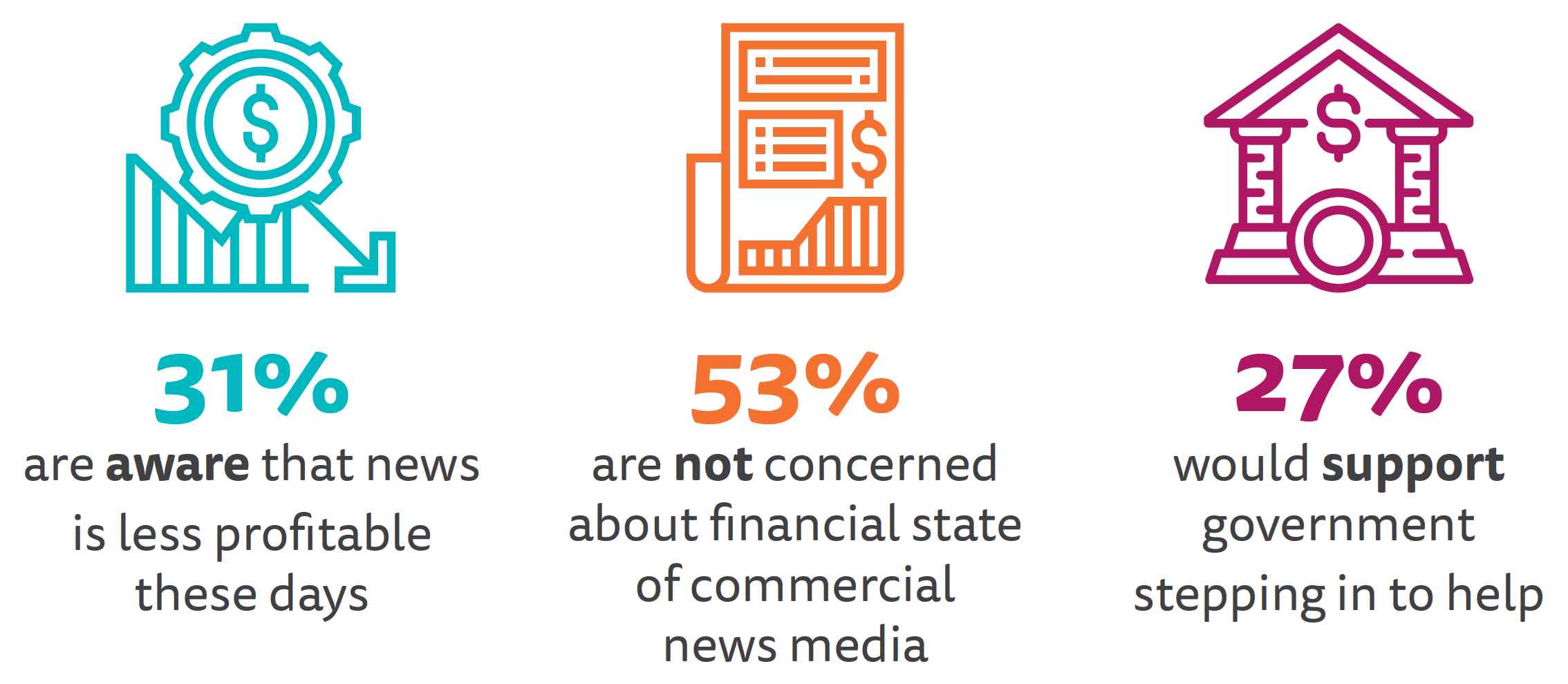

Though many publishers, policy makers, and academics worry about the future of local (and national) media, our report this year suggests that most ordinary people don’t share these concerns. Across countries, only around a third (31%) were aware that many commercial news outlets were less profitable than they were a decade ago and the majority (53%) are not worried about this. Just a quarter (27%) would support any government intervention to help commercial media, with another three in ten (29%) not having a view on the issue.

Public attitudes towards commercial media financing – 33 markets

Only in a very small number of countries, such as Portugal, where the media have been especially hard hit by structural change, do we find more support than opposition (41%/35%) to the use of public money to help commercial media. Support is particularly low in Denmark (16%) and Sweden (22%), two countries with longstanding government subsidy schemes for commercial media. It is lowest in the UK (11%) – which may help explain why a review proposing more funding for public-interest journalism has effectively been shelved.5

Some governments have offered temporary support for publishers during the Coronavirus crisis in the form of furloughs, handouts, and tax relief, but it is not clear that there is currently public support for larger and more permanent interventions. There will be pressure to support many different parts of the economy over the next few years – especially health systems and education. Given the low levels of public awareness of the challenges facing the business of news, and low levels of support for government intervention – and more broadly low levels of trust in news in many countries – it is not clear that it will be politically attractive to prioritise supporting journalism at the expense of other priorities that enjoy greater public awareness and support.

Trust is up and so are trust gaps

Overall trust in the news (44%) has rebounded strongly (+6) over the last year in almost all countries – as has trust in the sources people use most often themselves, which is up four points to 50%. Finland remains the country with the highest levels of trust (65%), having increased by nine points, while the US now has the lowest levels (29%). We also find a growing trust gap between the news sources people generally rely on and the news they find in social media and search, which remain unchanged on a like-for-like basis.6

Proportion that trusts most news most of the time – all markets

We can speculate that this higher trust in the news – and in the sources people use themselves – could be related to extensive coverage of Coronavirus. This may have made the news seem more straightforward and fact-based at the same time as squeezing out more partisan political news in some countries. The United States is clearly an exception following deep divisions over a ‘stolen election’ and the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd. The US is one of the few countries not to have seen an increase in trust this year.

Some countries have a trust deficit

We can recut these figures to include the proportion that distrusts the news. This gives us a good indication of how polarising the news media’s reputation might be in particular countries. In the United States there are more people who distrust the news than trust it, leaving a deficit of 15 points. But in Scandinavian countries, like Denmark, a very small proportion say they distrust the news, leaving a large net positive score of 48 points.

Political divides fuel much of this mistrust in the United States, with those who self-identify on the right being more than twice as likely to distrust the news compared with those on the left. Resentment and anger are stoked by polarised TV networks such as right-leaning Fox News, One America News, and Newsmax and left-leaning CNN and MSNBC.

Other countries with a net positive trust score include Finland and the Netherlands. Those with a deficit include Bulgaria (-12), France (-8), Hungary (-6), Chile (-4), and Argentina (-3).

Perceptions of media fairness

Further evidence of what is driving mistrust comes this year in a series of questions we are asking about fairness of mainstream media coverage. We can compare these answers with information we hold about age, gender, ethnicity, education, and political views. In the United States we can use this data to see how attitudes towards the media are affected by politics. Three-quarters (75%) of those who self-identify on the right feel that media coverage of their views is unfair and this compares with just a third of those on the left. Younger people (U35s) are also more likely to feel that the media is unfair when compared with older groups.

By contrast, in the UK both the left and the right feel that their political views are unfairly covered by the media. Differences over age are even more stark, with the youngest group (U25s) feeling least fairly represented by the media. Gender differences are perhaps smaller than one might expect, but more pronounced among younger people. In Germany, we find a similar problem with 18–24s and also with those on the right, who have weaponised terms like Lügenpresse (lying press) to express their unhappiness.

Across much of Western Europe we find it is the 18–24 age group that feels least fairly represented by the media and also that there is too little coverage of the issues they care about. This may explain why this group tends to embrace alternative and diverse views it finds in social media – with four in ten (40%) across markets saying this is now their main source of news. These findings may provide a starting point for news media genuinely interested in connecting with a younger generation – who are unlikely to pay attention to, let alone pay for, news that they often feel is both unfair and uninteresting.

In an era of greater polarisation, silent majority strongly supports impartial and objective journalism

The growth of online and social media has encouraged news organisations and individuals that take more overtly partisan positions than in the past. Online distribution has enabled an explosion of unregulated opinion in video, audio, and text. GB News is a new venture in the UK which aims to provide an alternative to what it claims is the ‘liberal and metropolitan bias’ of established news outlets, perhaps inspired by the commercial success of Fox News in the United States. All of this is putting new pressure on notions of impartiality and objectivity, which describe journalists’ attempts to represent all sides fairly and without biases.7

Our survey, backed up by qualitative interviews in four countries, shows that the public still strongly supports the ideals of impartial and objective news, while recognising that they themselves are sometimes drawn to more opinionated and less balanced content.

Across countries, around three-quarters (74%) of our sample think that news outlets should reflect a range of views rather than take a position about a news story. Most also think that news outlets should try to be neutral on every issue (66%) but a substantial minority (24%) feel that there are some issues where it makes no sense to try to be neutral. While their overall views are similar to the population at large, younger groups are slightly less attached to impartial or neutral news, especially in the case of some burning issues of social justice

Equal time for all sides?

Another key debate is the extent to which impartiality should involve trying to balance different views on social and political issues by allocating similar amounts of time to each side. Critics argue that this approach, when applied to an issue like climate change, can lead to a ‘false equivalence’, where one set of views underpinned by strong scientific evidence is ‘balanced’ by views that lack significant support – and thus create a false impression in the minds of the audience. Despite this, almost three quarters of our sample (72%) felt it was better to give the same amount of time to different views. Fewer than one in five (17%) felt less time should be given to those with weaker arguments.

When pressed, in focus groups, around specific examples (e.g. whether anti-vaxxers, racists, or climate change deniers should be given equal time), a more nuanced position emerges. In both the survey and focus groups younger groups were more likely to see the dangers in giving equal time to weaker arguments. The greater diversity in these generations and greater exposure to social media may make them more sensitive to the harm that can be done by extreme and hateful views.

Many traditional media companies have been actively thinking about the implications of these complex questions. The new BBC Director General, Tim Davie, has declared that impartiality is more important than ever, but he says this does not mean that journalists cannot call out the truth or take a strong position if supported by the facts.8 Guidelines may need to be updated to take account of changing consumer expectations – as well as how journalists should conduct themselves in more informal settings such as social media and podcasts.

Misinformation and the role of coronavirus

Our survey this year shows that concern about misinformation is a little higher this year at 58% (+2). There is most concern in Africa (74%), followed by Latin America (65%), North America (63%), Asia (59%), and the lowest in Europe (54%).

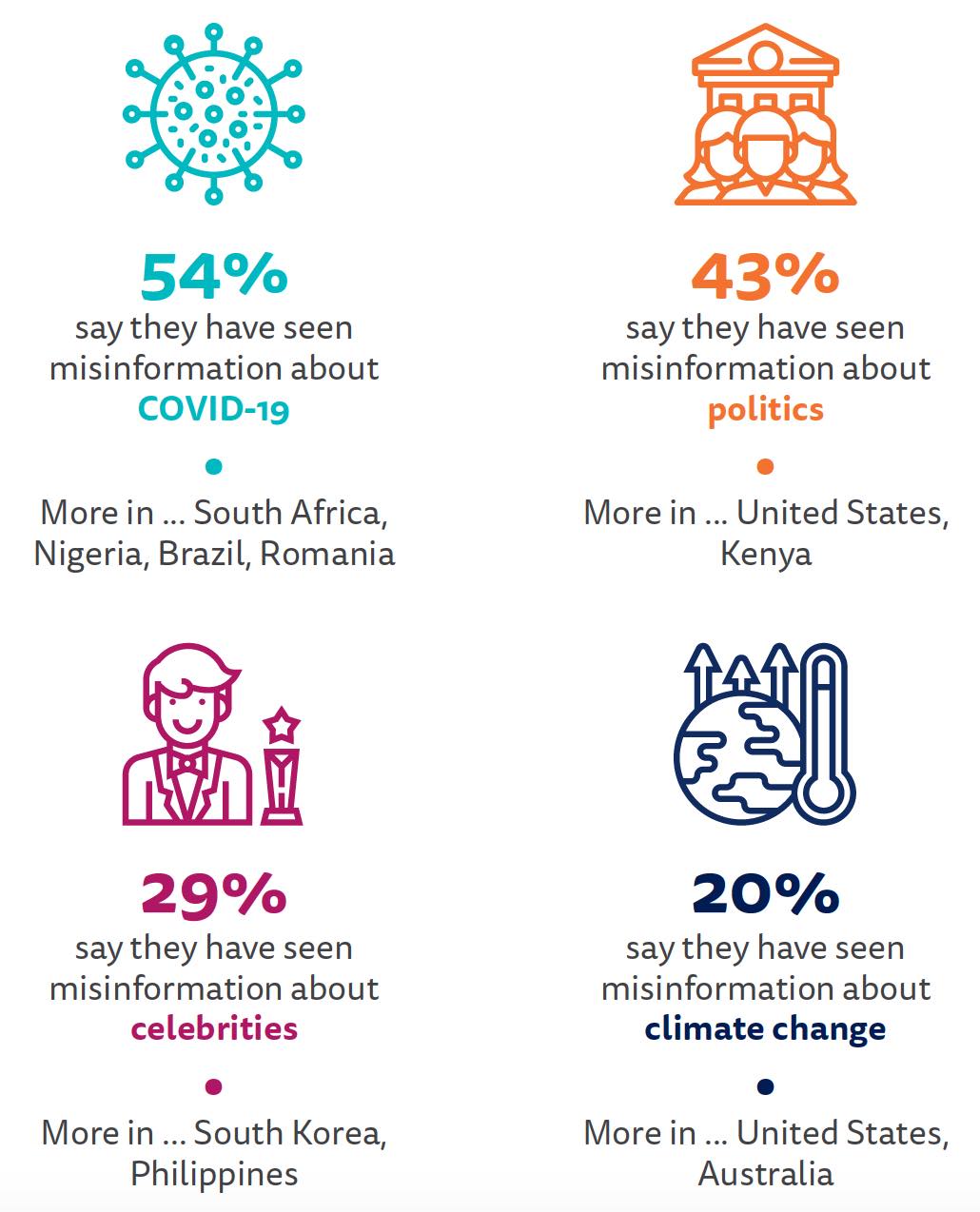

To understand broad areas of concern we can break this down further into topics. This year people claim, on average, to have seen more false and misleading information about Coronavirus (54%) than they have about politics (43%). Other topics of false information relate to celebrities such as actors, musicians and sports stars (29%), products and services (22%), and climate change (20%). Only in Kenya does perceived exposure to political misinformation outstrip that about COVID-19.

Proportion that thinks they have seen false and misleading information about each of the following in the last week - all markets

Misinformation about COVID-19 has been a particular problem in African countries such as Nigeria and South Africa, where false rumours and conspiracies have spread quickly through social media.9 Spread of false information about COVID is also widespread in Central and Eastern Europe (Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria) as well as in much of Latin America and parts of Asia.

Where does misinformation about Coronavirus come from?

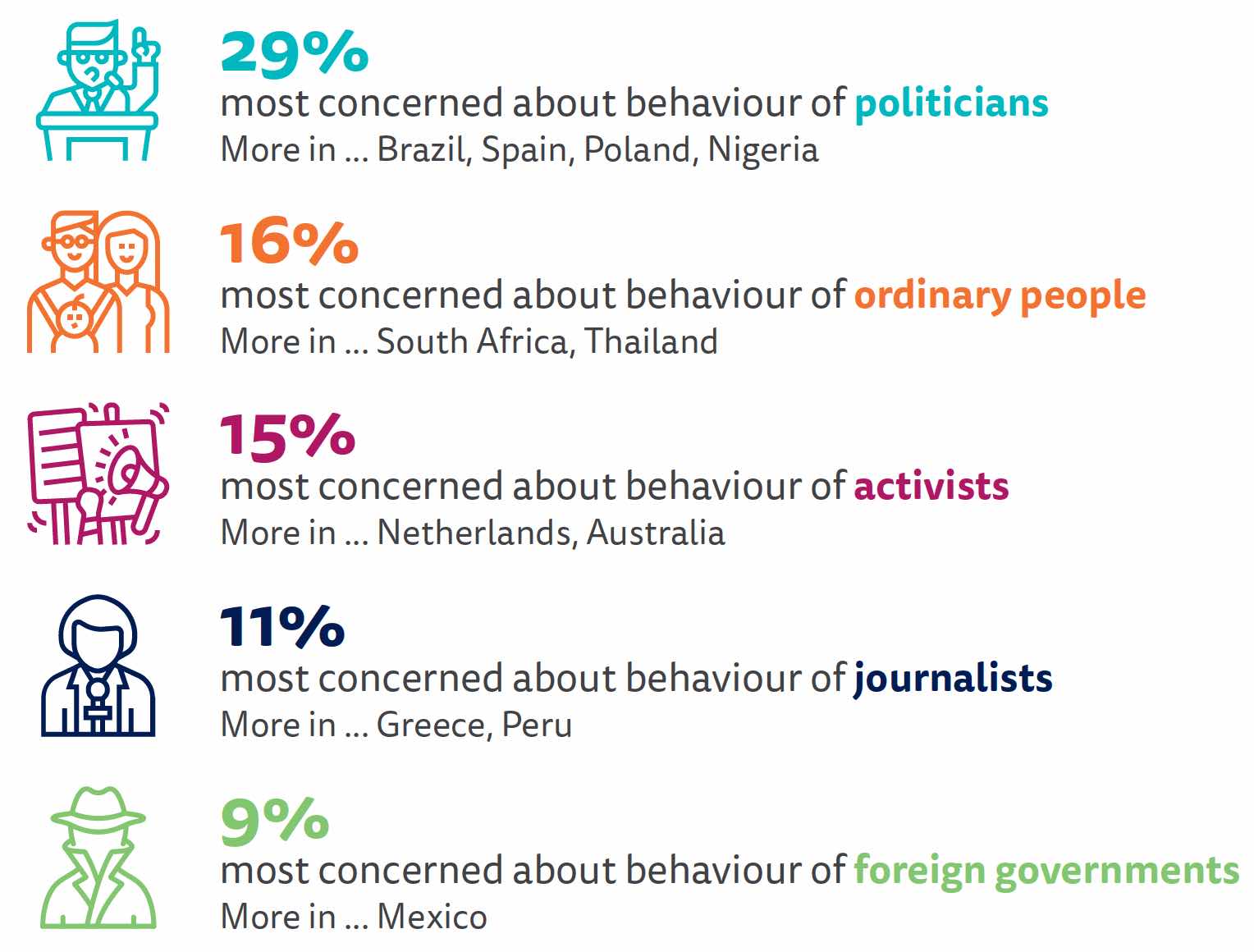

In general, we find the highest level of concern about the behaviours of national politicians (29%) when it comes to spreading misleading information about COVID-19. This is highest in countries like Brazil (41%) where fact-checkers identified almost 900 false or inaccurate statements on the subject by President Jair Bolsonaro during 2020.10 Concern was also high in Poland (41%) where the ruling Law and Justice party has been accused of politicising the pandemic and in the United States (33%) where Donald Trump first suggested the virus would ‘go away’, downplayed the value of mask-wearing, and then suggested injecting disinfectant as a miracle cure.

Proportion that finds each most concerning for COVID-19 misinformation – all markets

When it comes to the channels through which COVID misinformation is spread, we find that there is most concern about Facebook (28%), followed by news websites and apps (17%), WhatsApp and other messaging apps (15%), search engines (7%), Twitter (6%), and YouTube (6%). But we also find major country and regional differences.

Proportion that finds each platform most concerning for COVID-19 misinformation – all markets

In much of the Global South – including Brazil, Indonesia, India, Nigeria, and South Africa – messaging apps such as WhatsApp draw the most concern. The closed and encrypted nature of this network can make it harder for fact-checkers and others to spot and counter damaging information. By contrast, in the UK and US, Facebook is seen as the main concern, with Twitter perceived to be the next most significant network. Facebook is also the main concern in the Philippines and Thailand where it is the key platform for news.

Given these results, it is not surprising to find that those who use social media or messaging apps most for news (main users) are much more likely to say they have been exposed to misinformation about Coronavirus (63%) compared with non-users (45%) – as well as about other subjects such as politics. These groups also tend to have lower trust in the news, potentially making them more open to believe alternative or conspiratorial narratives.

Messaging apps continue to grow; TikTok and Telegram make their mark

For the last seven years, we have been tracking the changing mix of social networks (a) for any purpose and (b) for news. The following charts show the aggregate picture across 12 countries we have been tracking since 2014. YouTube now matches Facebook in terms of use for any purpose, having added 9pp over the last eight years. WhatsApp use (52%) has tripled over the same period and Instagram has grown five-fold, though it seems to be levelling off. TikTok and the messaging app Telegram are growing rapidly – the latter part of a continuing shift to more private networks.

Across these 12 countries, around two-thirds (66%) now use one or more social networks or messaging apps for consuming, sharing, or discussing news. But the mix of networks has changed significantly over time. Facebook has become significantly less relevant in the last year, while WhatsApp, Instagram, TikTok, and Telegram have continued to attract more news use.

As previously noted, we find different patterns of usage in the Global South, with higher reliance on YouTube in Asia and more focus on WhatsApp and Instagram in Latin America and Africa. Telegram usage has doubled in some countries over the last year and is used for news by 23% in Nigeria, 20% in Malaysia, and 18% in Indonesia.

Next generation protest focused on newer networks

Newer mobile-based social networks like Instagram and TikTok have become central to a new wave of protests by younger people across the world this year. In Peru, anti-corruption protests were focused around the hashtag #semetieronconlageneracionequivocada (they messed with the wrong generation). TikTok, a vertical video platform that builds on Instagram and Snapchat stories, played a part in protests across Southeast Asia including Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar. In many cases, the authorities seem to have been blindsided by a platform that they don’t understand – with its quirky sense of humour and its distinct language of musical memes, emojis, and hashtags.

Elsewhere it has been used to articulate solidarity around the Black Lives Matter movement or with the victims of Coronavirus.

News organisations have also been experimenting with a platform that is skewed towards the ‘hard to reach’ under-25 demographic. The Washington Post was an early pioneer using the platform, amongst other things, to encourage young people to vote. The BBC’s Sophia Smith Galer has pioneered experimental storytelling on TikTok – such as creating a viral sea shanty about the blocking of the Suez Canal by a container ship, and the German public broadcaster ARD has built a quirky TikTok presence for its daily news show Tagesschau.

How much attention do news organisations get in social media?

This little-researched question has been a key focus for our report this year as we dig more deeply into how people are using different networks for news. We know that many journalists put a lot of effort into cultivating their presence on Twitter and Facebook and to some extent this seems to be paying off. Across countries, our respondents say that they pay most attention to mainstream media outlets when consuming news in both Twitter (31%) and Facebook (28%) – considerably more than for politicians, alternative news sources, or other influencers. But the democratising impact of social media is also laid bare in the following chart, with significant attention going to the views of ordinary people across all networks, also for news. In networks such as Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok, the focus is also firmly on personalities – such as celebrities or other influencers – leaving journalists playing second fiddle, even when it comes to news.

What are the motivations for using different social networks for news?

When asking people to choose their main motivation for using a network we find clear differences between Twitter, which users see as a good place to get and debate the latest news, and other networks like Facebook – where people are ‘mainly there for other reasons’.

Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok are very clearly seen as a fun and entertaining way to pass the time, in keeping with the younger and more playful nature of these networks in general. YouTube news users have a range of motivations, including a strong focus on looking for alternative perspectives on the news

There are exceptions, however, to this general pattern. In Malaysia and the Philippines Facebook has become much more of a destination for news than Twitter, while in South Africa YouTube is also popular for latest news. In Brazil people routinely access news across four or five different networks, using them for subtly different purposes.

Newer youth-orientated networks represent a significant challenge for mainstream media. News is largely incidental and the expectations of snappy, visual, and entertaining content do not always come naturally to newsrooms staffed by older journalists with a focus on traditional formats. As we have seen, experiments are ongoing but tapping into these networks with timely, relevant, and engaging content remains a work in progress.

Gateways and intermediaries

In terms of access points, habits continue to become more distributed – as ‘younger’ preferences for social media and search become more mainstream. Across all countries, just a quarter (25%) prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app – down three percentage points compared with last year and down seven points compared with 2018. Under-35s have a weaker connection with websites/apps (18%) and are much more likely to prefer to access news via social media (34%).

These trends towards aggregation and social gateways are relentless, seem to have been unaffected by COVID-19, and explain why negotiations with publishers over money (e.g. Australia, France, UK) are so critical. Younger groups are not going to abandon the platforms and aggregators, which provide a quick and convenient way to check the news, but many publishers are unhappy with the current arrangement, which in most cases involves providing content in return for access to audiences. They argue that this approach is unsustainable, especially for expensively produced original reporting, and are demanding better terms, if necessary brokered by governments.

Smartphone dependence grows during lockdowns

Across countries, almost three-quarters (73%) now access news via a smartphone – up from 69% in 2020. Part of this is a continuation of trends which have seen the mobile phone overtake the computer as the primary access point in almost all countries, but Coronavirus may also have played a part. Governments around the world have focused on these personal devices to communicate on restrictions, to get citizens to report symptoms, and to book appointments for vaccines. Smartphones have become critical for keeping in touch with friends or booking takeaway food and drink – but also for discovering and consuming news. Computer news access by contrast has fallen from 49% to 46% (-3pp). We see smaller effects in some countries which have had fewer restrictions on movement such as Sweden and South Korea.

The next chart illustrates change over time in the UK, with the gap between smartphone and computer growing to 25 points. We also see an accompanying growth in the proportion of Britons accessing news more frequently.

It is worth noting, however, that Western Europeans tend to lag behind those in the Global South, where so many have grown up with the device as the primary gateway to the internet. Looking at three countries that are new to our survey (Indonesia, Nigeria, and Peru) we find much higher levels of smartphone use for news than in EU countries.

Mobile aggregators and mobile alerts

As smartphones have grown in importance, so too have news alerts. In terms of weekly reach, they have tripled in most countries since 2014 and quadrupled in the United States, where they now reach around a quarter (24%) of the adult population. News alerts are used fairly evenly across age groups. Email is mainly used by older groups.

Some of these alerts come from the apps of traditional media companies but mobile aggregators also seem to be benefiting. Apple News has grown significantly this year in the US, reaching a third of iPhone users, 14% of our overall sample, and 20% of under-35s.

Mobile aggregators play a significant role in many Asian markets, including some of those that are new to our survey. Naver and Daum (Kakao) dominate in South Korea while Yahoo/Line is the major player in Japan. Line Today has gained impressive reach across Taiwan (44%), Thailand (36%), and Indonesia (20%), while India has a wide range of personalised mobile aggregators focusing on news and entertainment, including Daily Hunt, News Republic, and NewsPoint.

These mobile aggregators have taken off in Asia, partly due to bundling with local phone operators, partly due to the stronger penetration of Android devices, and partly because of a history of early mover advantage. But this does not fully explain regional differences. Upday comes bundled with many Samsung phones in Europe and Latin America but only reaches 8% in Brazil, 6% in Germany, and 4% in the UK.

Podcasts and the rise of audio

News podcasts, including those about Coronavirus, performed strongly in the early stages of the pandemic – in some cases reaching the top of the podcast charts. Podcasts have become a key part of many lockdown routines with more consumption at home – though there has also been disruption to the daily commute, traditionally a key time for listening. The net impact on consumption seems to have been neutral, with 31% accessing a podcast in the last month (the same as last year) across 20 countries where we feel confident the term is sufficiently well understood and where samples are not skewed by high levels of education.

Podcasts are particularly popular in Ireland (41%), Spain (38%), Sweden (37%), Norway (37%), and the United States (37%). Fewer people access podcasts in the Netherlands (28%), Germany (25%), and the UK (22%), though, as we’ve suggested before, this may be because many people are consuming from public service radio apps where they may be perceived as radio ‘on demand’ rather than podcasts.

Platform mix is changing

Spotify, Amazon, and Google have been investing in podcasts over the last few years as they seek to capitalise on surging demand and break Apple’s dominance. Spotify reportedly paid more than $1m for exclusive rights to the Joe Rogan podcast and signed Barack Obama and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle to produce regular programming – as well as introducing video functionality into its app. The growth of video podcasting, accentuated by the use of tools like Zoom during the pandemic, is opening an even wider range of options for distribution and leading to more problems of podcast definition for researchers. All this activity is also changing the platforms through which consumers access podcasts. Spotify has overtaken Apple in some markets, YouTube is ahead in others, while public broadcasters play an important role in a few.

In the last few years there has been an explosion in the supply of podcasts with two million different shows now available in the Apple index. Demand for podcasts is not growing at the same rate, so discovery and awareness remain the biggest problems. Our data show that more people discover shows through recommendations from friends, family, or colleagues rather than promotion such as in-app recommendation or advertisements.

Search is also important, particularly in Europe, but the initial spark will often have come from a personal recommendation. Promotion via apps (e.g. Apple Podcasts, BBC Sounds) or via TV and radio trails or newspaper articles are also important for some.

The commissioning of more high-quality original content by platforms is bringing audio programming to a wider and more mainstream audience, but it is also raising new questions for public broadcasters. Many worry that platforms will take much of the credit/attribution for public content and exert increasing control over access and discovery.

Europe and Asia lag behind the United States in awareness of podcasts

Awareness of podcasts is low in Japan, where 40% of those that don’t use them say it’s because they don’t know what they are. The European average of 17% that are still not aware is almost twice as high as in the US, suggesting there could be an opportunity to grow with extra marketing and promotion. Others that are not yet using them say that podcasts are too long, or that they don’t know how to find good ones. Others still say they don’t have enough interest or enough time. These may be harder dials to shift.

Overall, podcasts remain a fast moving and dynamic part of digital consumption. They are of particular interest to publishers because they attract younger and more affluent users that are highly sought by advertisers – and are potentially the next generation of subscribers.

Smart speakers could drive further audio growth

The shift to audio is being driven by new devices such as smart speakers and by platform services such as short podcasts or other audio items that can be called up using voice interfaces. Amazon and Google are the key market makers here and both have a renewed focus in promoting innovative audio formats including podcasts. Smart speakers now reach more than a fifth of the UK adult population (22%) and 15% in the United States, and Germany. But only a minority use the devices for any kind of news (6% in the UK and 5% in the United States).

Conclusion

This year’s data contain some good news for publishers and for those worried about the future of the news industry. More people have sought out accurate and reliable information during this crisis with trusted, high-quality brands benefiting most in a number of countries. The overall trust gap between mainstream media and social media has also grown significantly. Some European public broadcasters can also take new confidence from data which show that audiences have valued their careful and impartial approach to the facts at a time when they have often struggled to keep up with rapidly changing behaviours. Commercial publishers that still rely on income from print or digital advertising have had a torrid time, but acceleration of digital plans as a consequence may put some on the long-term path to survival.

Consumers have rapidly adopted new digital behaviours during lockdowns and this is opening up new digital opportunities at the same time as highlighting the next set of challenges. Our report shows that subscription and membership is becoming a sustainable model for a growing number of high-quality and niche publications, and in a few countries for local media groups and individuals. But it is also clear that paid content is not a silver bullet for all publishers. Nor will it work for all consumers. The vast majority are still not prepared to pay for online news and with more high-quality content disappearing behind paywalls there are pressing concerns about what happens to those who have limited interest or who can’t afford it.

Worryingly, our data also show a historic decline in interest in the news overall. In this respect, our findings that both political partisans and young people feel unfairly represented will be especially troubling for media companies looking to build engagement both across political divides and with the next generation. Indeed, one of the most striking findings in this year’s data is the radically different habits of under-25s (so-called GenZ), even when compared with the millennials that came before them. These digital natives are less likely to visit a news website, or be committed to impartial news, and more likely to say they use social media as their main source of news. Deeply networked, they have embraced new mobile networks like Instagram and TikTok for entertainment and distraction, to express their political rage – but also to tell their own stories in their own way. Engaging these audiences is proving challenging for newsrooms that are mostly staffed by journalists who consume news in completely different ways.

In an era where news consumption has become more abundant, more fragmented, and more fractious, media companies face a choice. They can try to build a deeper relationship with a specific audience or demographic – representing and reflecting their views and aspirations. This journalism may need to take a clearer ‘point of view’ but could also build deep trust with that specific group. On the other hand, media companies could choose to try to bridge these divides with services that work for the largest number of people possible – something much of the public say they want. In this case, the challenge will be whether journalism that balances different points of view can engage audiences sufficiently – but also avoid getting caught up in the partisan and cultural battles that have been such a feature of the last few years.

This tenth edition of the Digital News Report comes at a time of immense challenge for the news industry. Year after year we’ve witnessed the shift towards more digital, social, and mobile consumption – slowly chipping away at the business models as well as the confidence of many media companies. Now the shock of COVID-19 combined with accelerating technological change is bringing things to a head – forcing a more fundamental rethink about how journalism should operate in the next decade, as a business, in terms of technology, but also as a profession.

Footnotes

1 https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/mar/25/television-licence-fee-preferred-option-fund-bbc-2038-mps

2 https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/media/media-trump-bump-slump/2021/03/22/5f13549a-85d1-11eb-bfdf-4d36dab83a6d_story.html

3 https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2021

4 https://www.poynter.org/locally/2021/the-coronavirus-has-closed-more-than-60-local-newsrooms-across-america-and-counting/

5 The Cairncross Review (Feb. 2019) made nine recommendations about the sustainability of the UK news industry: https://www.pressgazette.co.uk/government-response-cairncross-review-institute-news-save-uk-journalism/

6 Taking the same 40 markets polled in 2020 we find trust in news at 43% (up five) and trust in social media unchanged at 22% and in search at 32%.

7 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/sep/05/does-journalism-still-require-impartiality

8 Tim Davie, introductory speech as Director General, September 2020: https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/speeches/2020/tim-davie-intro-speech

9 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-52819674

10 https://www.statista.com/statistics/1118867/bolsonaro-fake-statements-coronavirus/