How a newspaper and a museum partnered to create a project on the Dutch colonial past

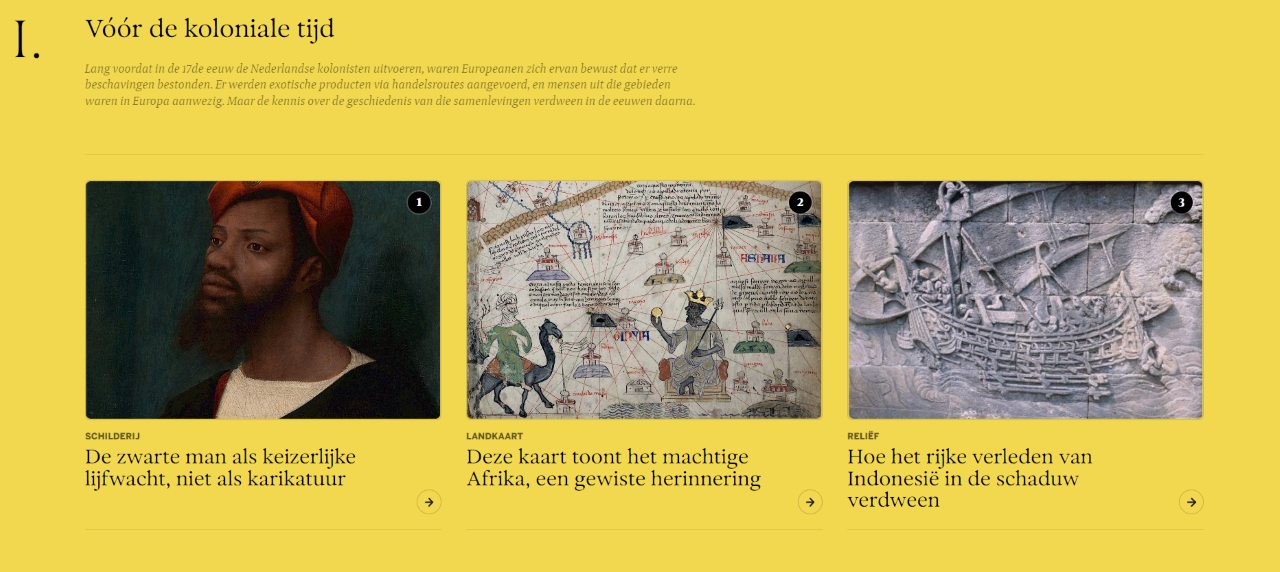

A screenshot of the project's landing page. Credit: De Volkskrant.

When the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant compiled the 50 most important objects in natural history as a series in 2007, the project was a resounding success. Known as De Bètacanon [or the “Beta Cannon”], it was a clever way to engage readers in science and history coverage, and was part of a national craze for “canonising” Dutch life: newspapers, museums and even local municipalities were creating authoritative lists of items or events that defined the history of a subject, even a whole city.

Fifteen years later, one of the original creators of the project, Tjerk Gualthérie van Weezel, who used to be the head of the paper’s domestic section and is now its energy correspondent, pitched the paper’s special projects committee on a chance to tackle another angle of Dutch history: colonisation.

The project Ons Koloniale Verladen In Vijftig Voorwerpen [Our colonial past In fifty objects] was launched in July 2022, following a close collaboration with the Netherlands’ world famous Rijksmuseum, and in particular with Valika Smeulders, the museum’s head of history. Every week until next June, the newspaper is releasing an essay about an object, starting in the pre-colonial era and ending in the present day. Each week, the essay is printed both in the print edition of the paper and online; for now, the project is purely a print and visual product, but a book compiling the essays is expected to eventually be released.

The paper’s special products fund backed the series, which involved a team of about five journalists internally, plus another 15 who produced essays tied to the objects—alongside a mix of curators and historians. The museum didn’t provide financial backing, but devoted time from Smeulders and other curators along with meeting space.

A timely project

The end of the project will coincide with the 150th anniversary of the end of Dutch slavery, when enslaved people in Suriname were officially released. That date was originally expected to coincide with what many experts believed would be a formal apology for slavery by the Dutch government, but on December 19, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte offered an official apology on behalf of the Dutch government in a speech at the national archives in The Hague.

“It is true nobody alive today bears any personal guilt for slavery,” Rutte said. “But the Dutch state bears responsibility for the immense suffering of those who were enslaved, and their descendants.”

The project’s inaugural essay in July made a frank admission that a decade ago, such attention to Dutch colonialism was “hardly imaginable.” The initiative is part of a wider reckoning in the Netherlands with the country’s colonial history and it comes on the heels of the Rijksmuseum’s blockbuster 2021 exhibit Slavery, the museum’s first to focus explicitly on the history of the Dutch slave trade.

Smeulders, who was one of the exhibition’s four curators, says there has been a slow shift in the understanding of Dutch history since she arrived in the Netherlands at 18, from Curaçao, to study at university.

She was surprised, she says, to find that Dutch history and colonial history were “kept separate,” a dynamic that was obvious in the previous canon projects.

“The Canons [in Dutch newspapers] before were mostly focused on national history, as if colonialism was something that happened outside of the Netherlands and that didn't have anything to do with the national history of the Netherlands,” said Smeulders, speaking over Zoom from Amsterdam.

“I can't even put it into words how important this is,” she says. “It feels like things are falling into place, finally, after about 20 years.”

How the project was built

The team behind the project included a large team of journalists, curators and researchers, who set out to trace the narrative of Dutch colonialism in objects large and small, beginning with a pre-colonial portrait of a prosperous royal bodyguard – a Black man – and a detailed map of Africa from 1375. The map shows that Europeans were well aware of the distinct cultures, languages and regions of the continent before colonisation, and tells the story of how this inconvenient knowledge was “wiped from the map.” Other items include a skeleton of the dodo, the first share of the Dutch East India Company, and a Tambú drum.

While the committee originally weighed the possibility of turning the project into a physical museum exhibit, some of the objects aren’t present in the Netherlands, including a brick at a fort once used for trading slaves on the coast of Ghana, and a relief in a Buddhist temple in Indonesia. Others, including a diamond expected to be featured later in the series, will hit directly on contentious questions of whether a European museum should include items removed from its former colonies at all.

Each essay was intended to produce an ‘aha’ moment, says Van Weezel. One essay looks at a portrait of two nutmeg pickers, and tells the story of the genocide of the people of Indonesia’s Banda Islands by Jan Pieterszoon Coen, an officer of the Dutch East India company who was intent on dominating the spice trade.

Coen is also the namesake of the Coentunnel, a motorway tunnel in west Amsterdam that is on the radio every day for its traffic snarls, and so a kind of aural wallpaper for life in the Netherlands’ largest city.

“For the first time, I really read the story of what this guy did,” says Van Weezel. “And to name a tunnel after a person that you know has willingly killed so many people, in a brutal manner—it’s really weird.”

Another moment of recognition included the quest for a photo of the Dutch-made brick at the Elmina fort in Ghana, which eventually involved a local guide going to the site itself. The arrival of the photo, snapped on the guide’s mobile a moment before, brought home the immediacy of colonial history, he says.

A nuanced portrait

Just as the project attempts to bring Dutch national history and colonial history into one thread, Smeulders says she and her colleagues, in picking and describing the objects, have sought to bring to life a nuanced portrait of what slavery and colonialism looked like.

That means conveying the essential violence and oppression of the colonial system, while at the same time, portraying the resistance, resilience and joy of the people who were trapped inside it. The ultimate aim was to portray the most “complete” view as possible, Smeulders says.

“It was war. We had to speak clearly about that,” she says. “And then you have to speak about all these cultures coming together, and what that meant. What were the mechanisms people used? To cope, to keep being human.”

The project comes at a moment when the Dutch public is re-examining itself and its history, leading up to the 150th anniversary. Besides the official apology, Van Weezel points out that the public is closely watching research on the colonial history of the Dutch royal family, and a conversation is ongoing about what a true accounting for the injustice of the colonial system would look like.

“A museum and more attention for the darker sides of history in our schools are among the often named steps to take,” he adds. “With our project we hope to contribute.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time