How Bellingcat collects, verifies and archives digital evidence of war crimes in Ukraine

A pink teddy bear lies on the ground in front of residential apartments destroyed by Russian military strikes in Kharkiv, Ukraine. REUTERS/Clodagh Kilcoyne

Before becoming a journalist, Nick Waters served as a British infantry officer. After doing a tour in Afghanistan, he enrolled in a Masters in conflict, security and development at King’s College. He wanted to know how foreign policy worked.

One day Waters saw his colleague Christiaan Triebert at the library, looking at a map and at a video of an airstrike. Triebert, who now works at the New York Times, told him he was trying to geolocate the attack. He explained what geolocation was, how it was done, why it was important.

Waters found it fascinating. He wanted to learn.

Waters took Matt Moran’s class on open source intelligence (also known as OSINT) and began to read Bellingcat, a website founded by Eliot Higgins in 2014 as a hub for a collective of investigators and citizen journalists around the world. After meeting Higgins in London, Waters started writing for Bellingcat – first as a volunteer, then as part of a growing staff.

From breaking news to collecting evidence

Born out of Higgins’ personal blog, Bellingcat published ground-breaking scoops on chemical attacks in Syria, the Salisbury poisonings, and the downing of the MA17 flight in Eastern Ukraine. As output and funding grew, the project became a nonprofit, created a stable newsroom and codified its editorial standards.

Around the same time, Bellingcat’s team realised their work could have a real impact in criminal justice. In August 2017, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant accusing Libyan citizen Mahmoud al-Werfalli of 33 murders. For the first time in history, nearly all the evidence came from social media posts. “The case suggested that Bellingcat had prospects beyond uncovering newsworthy facts,” Higgins writes in his book We are Bellingcat. “Whether we considered it or not, we dealt in legal evidence now, often the first in the world to discover it, and the only ones archiving it. Our responsibilities had grown.”

Courts only admit evidence if chain-of-custody is documented to a high standard. This also applies to pictures or videos posted on social media, which can corroborate or debunk survivor testimony and other sources. So Higgins and his colleagues started to take archiving more seriously and worked with the Global Legal Action Network (GLAN) to create the Yemen Project, an initiative whose focus was examining the Saudi-led aerial bombing of the country. The project was led by Yemeni journalist Rawan Shaif and Waters, the former infantry officer who now worked for Bellingcat.

The focus of the Yemen Project was finding whether British munitions were being used on civilian targets. With the help of GLAN, Shaif and Waters created a protocol and tested it at a four-day hackathon in January 2019. Their goal was to identify any alleged airstrikes, collect and verify any social media evidence about them, and then archive this material with the help of Mnemonic, an organisation that helps preserve vulnerable digital information in war zones such as Syria, Sudan or Ukraine.

The blueprint for Ukraine

As Waters was preparing a second iteration of the Yemen Project, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “We had a structure and a methodology, and people were posting huge amounts of images and videos that could be analysed,” he says. “So we updated our proposal, built our team and started to investigate.”

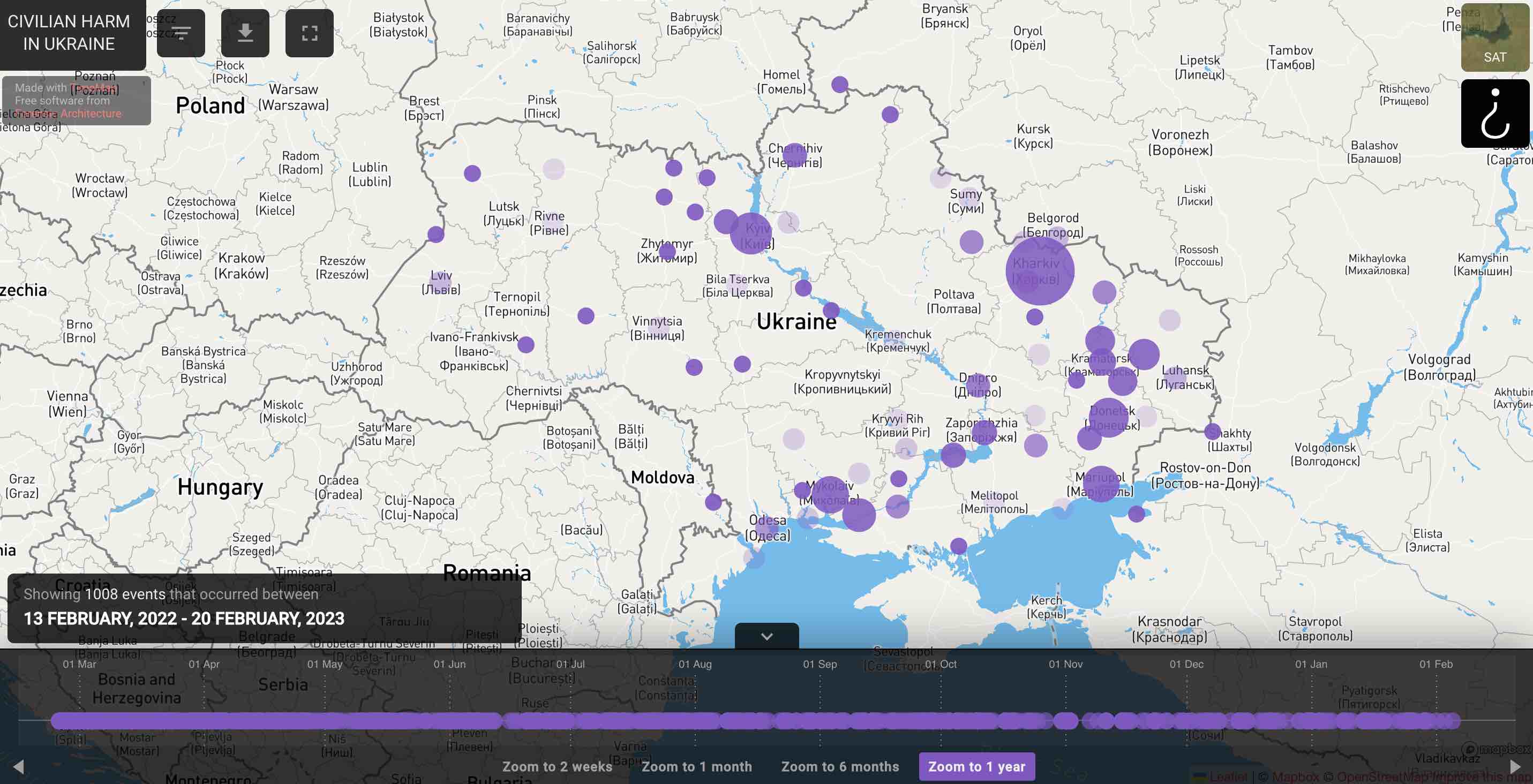

Bellincat’s Ukraine database intends to be a living document. Collection started on the first day of the invasion and Bellingcat intends to keep updating it until the end of the conflict. The database is made of incidents that have resulted in potential civilian harm, including rockets or missiles impacting civilian areas and the destruction of civilian infrastructure. They’ve been logged and mapped by Waters’ team at Bellingcat and by the Global Authentication Project, a community of open source researchers led by Hannah Bagdasar. All contributions are vetted by Bellingcat researchers.

“We verify the events and place them into this evidentiary database which in theory could be used as evidence in court,” Waters says. “We are pretty confident that our methodology works since we tested it during a mock hearing in 2021.”

Waters works with three full-time colleagues and another six help on a part-time basis. The team includes lawyers and Russian and Ukrainian speakers, but its focus is limited. “We can’t do something we are not equipped to do”, Waters says. “We can’t interview witnesses, for example, because we are not trained to do that and we don’t want to contaminate testimony. So we don’t focus on things like Bucha or the bombing of the Mariupol drama theatre. We tend to focus on events that are slightly less high-profile but where we can really apply our methods effectively.”

The events documented so far

At the time of this writing, Bellingcat’s TimeMap documents 1,094 examples of bombings, shootings and airstrikes and places them in time and space. Up to 190 of the events documented are attacks against schools, cultural sites and healthcare facilities. A big proportion happened in big cities such as Kharkiv (219), Kyiv (95), Mykolaiv (74), Mariupol (70) and Kherson (57).

Users can view incidents by week, by month and by longer periods, and use filters to see specific types of events – for example, incidents that impacted residential, industrial or healthcare facilities. Users can also locate events in specific cities and regions by zooming in. Whenever videos or images could reveal the identity of the location of a content creator, Bellingcat has taken steps to protect their privacy while still including the relevant information.

I asked Waters to walk me through what he and his team would do with one of these incidents. “A physical event will often have digital ripples, and our job is to collect that digital ripple, verify it and place it in time and space,” he says. “Let’s say we’ve seen an event occur. Then we assign an investigator who’ll collect as much digital information as possible about the event. Then the investigator will check other reports on the same event, and that body of images, videos and text messages is the digital ripple we aim to capture.”

This digital ripple, Waters stresses, is very difficult to fake or recreate. As our own research has shown, misinformation often involves some kind of reconfiguration in which a piece of content is spun, twisted or recontextualised. So placing pictures and videos of an airstrike in time and space helps prove it belongs to the current war, and not to one in the past.

As Higgins explains in his book, Bellingcat’s investigators use software platform Hunchly, which tracks what they click and view, preserving every page, so that they retain the entire process, in case another researcher or a prosecutor wants to consult it in the future.

It’s important to stress investigators at Bellingcat focus on what they think they can do best. “The reason we have such a strict scope is because we know we are good at doing this, and the aim is that this information is combined with other types of evidence at a later date,” Waters says.

How to archive criminal evidence

Once Bellingcat has placed an image or a video in time and space, and referenced it against other pieces of content, they need to archive it in case it disappears from the internet, and do it in a way that would make it acceptable in a court of law.

“Our friends at Mnemonic take any piece of content, download it, feed it into a hashing algorithm and that algorithm generates a hash, which is a string of letters and numbers,” Waters says. “This piece of content is placed into a vault and the hash is kept separate. So if 10 years down the line an archived video ends up in court, the hash proves the video hasn’t been tampered with while it was in custody of Mnemonic.”

If Bellingcat’s work on Yemen often dealt with mass casualty events, their work on Ukraine focuses on smaller events happening over a much wider area. This makes it even more important to see beyond each episode and find any patterns. “We’ve seen widespread use of cluster munitions, especially in residential areas,” Waters says. “We’ve also seen use of incendiary munitions mostly on the front lines and shooting events in highways, especially in the first couple of months. Several journalists were killed in this kind of event. We’ve also seen strikes on wheat fields and on grain warehouses.”

OSINT versus Seymour Hersh

On 8 February award-winning journalist Seymour Hersh published a long piece on his personal Substack arguing the US government had destroyed the Nord Stream gas pipeline. The article was based on a single anonymous source. Since its publication, journalists such as Joe Galvin, Oliver Alexander and Fermín Grodira have debunked some of its claims.

This event is beyond the scope of Bellingcat’s Ukraine project. But Higgins and his colleagues have debunked similar claims by Hersh in the past. This piece by Higgins on the Khan Sheikhoun chemical attack is a good example. So I wanted to know what Waters made of Hersh’s latest piece and why what he does is so different from Bellingcat’s work.

“It’s quite frustrating that someone who did some fantastic work in the past has reached the point where he doesn’t know what’s true and what’s false anymore,” Waters says. “What we do is just the opposite. We are not just looking at a single source telling us stuff which is clearly fabricated. We are combining multiple pieces of information and verifying them painstakingly to demonstrate that these events took place. Back in 2017, when his work was questioned, Hersh said, ‘I’ve learnt just to write what I know and move on.’ That’s not what we do. We are putting our research into a database so it’s preserved for the long term because our ambition is for our findings to be tested in court.”

As this piece by award-winning journalist Dhruti Shah stressed recently, reviewing violent videos as Waters and his colleagues do can have an impact on people investigating the digital footprint of violent events. Back in 2019, open source intelligence pioneer Andy Carvin wrote this moving blog post about his own diagnosis with PTSD.

Waters says that Bellingcat has put in place policies to mitigate this kind of trauma. Everyone gets training and is offered regular sessions with psychologists specialised on these issues. “This kind of work can have a pretty bad effect on people,” he says. “Different people have different triggers. But there are a few basic steps you can take to mitigate this: watching something in black and white, watching with the sound off, using the scroll bar to look through very quickly, even holding a piece of paper to hide part of your screen. It’s important that people know there’s a supporting team around them. It’s important they know they can say, ‘Actually, I can’t do this today. I’m going for a walk.’”

An arc bending toward justice?

Bellingcat has collected evidence on conflicts like Yemen or Syria, where the chances of achieving justice in the short term are almost non-existent.

The situation in Ukraine is different. The country still has a functioning justice system. Prosecutors and police officers are already collecting evidence and building cases. Identifying perpetrators through witnesses and open source evidence is possible: there’s a lot of information on who’s done what.

“Taking perpetrators into custody will be very difficult,” Waters acknowledges. “I may be proved wrong tomorrow. But I don’t think the Russian state is going to collapse overnight and I don’t think they are going to release any perpetrators into the custody of any kind of justice system. However, sometimes the situation does change. What happened in Yugoslavia [where war criminals were prosecuted after war] is a good example. We should also keep in mind that many of these people are still on the battlefield, which is a relatively fluid place. People do surrender.”

Neither Waters nor his colleagues are going to stop collecting evidence any time soon. “There’s a small chance that this information may be used as evidence,” he says. “But that small chance is a big enough chance for me to want to do it. If you give up hope completely, then it’s never going to happen. But if you do it, there’s always that chance.”

In every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s of sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time